Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance

| Buffalo Child Long Lance | |

|---|---|

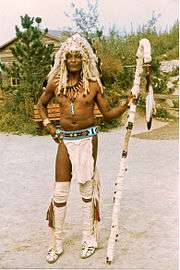

|

Sylvester Clark Long in Denver, Colorado, 1923 | |

| Born |

Sylvester Clark Long 1 December 1890 Winston-Salem, North Carolina |

| Died |

March 20, 1932 (aged 41) Los Angeles, California |

| Pen name | Long Lance |

| Occupation | Journalist, writer |

| Nationality | American |

| Citizenship | United States |

| Education |

Carlisle Indian School St. John's Military Academy |

| Genre | Journalism, autobiography |

| Notable works | Long Lance |

| Notable awards | Admitted to Explorers' Club |

Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance (December 1, 1890 – March 20, 1932), born Sylvester Clark Long, was an American journalist, writer and actor from Winston-Salem, North Carolina who became internationally prominent as a spokesman for Indian causes. He published an autobiography, purportedly based on his experience as the son of a Blackfoot chief. He was the first presumed American Indian admitted to the Explorers Club in New York City. After his tribal claims were found to be false, Long Lance was dropped by social circles.[1] :20m,41s-21m,51s He claimed to be of mixed Cherokee, white and black heritage, at a time when Southern society imposed binary divisions of black and white in a racially segregated society.

Early life and education

Long had ambitions that were larger than what he saw of his future in Winston, where his father Joseph S. Long was a janitor in the school system. In that segregated society, African-Americans had limited opportunities.[2] Long first left North Carolina to portray Indian characters in a "Wild West Show".[3] During this time he continued to build upon his (later proven to be fraudulent) stories of being Cherokee.[4]

In 1909, Long claimed to be a half-Cherokee when he applied to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School and was accepted.[3] He also lied about his age to gain admission. He graduated in 1912 at the top of his class, which included prominent Native Americans such as Jim Thorpe and Robert Geronimo, a son of the famous Apache warrior.[3]

Long entered the St. John's and Manlius Military academies in Manlius, New York with a full musical scholarship, based on his performance at the Carlisle School.[5]

Career

Long returned to Canada as an acting sergeant in 1919, requesting discharge at Calgary, Alberta. He worked as a journalist for the Calgary Herald. Canada had de facto segregation and a climate in which the government had discouraged black immigration from the US. During this time in both Canada and the US it was common for those of African heritage to instead claim Cherokee or Blackfoot. "It is not surprising that in such a climate...Long Lance felt that he was safer, and that he could go further, by disavowing any connection, cultural or racial, to blackness."[6]

He presented himself as a Cherokee from Oklahoma and claimed he was a West Point graduate with the Croix de Guerre earned in World War I. For the next three years as a reporter, he covered Indian issues. He criticized government treatment of Indians and openly criticized Canada's Indian Act, especially their attempts at re-education and prohibiting the practice of tribal rituals.[3] To a friend, Long Lance justified his decision to assume a Blackfoot Indian identity by saying it would help him be a more effective advocate, that he had not lived with his own people since he was sixteen, and now knew more about the Indians of Western Canada.[7] In 1924, Long Lance became a press representative for the Canadian Pacific Railway. By 1926 he handled press relations for their Banff Springs Hotel.

Through these years, Long also entered the civic life of the city, by joining the local Elks Lodge and the militia, and coaching football for the Calgary Canucks.[8] These activities would not have been possible had he honestly represented himself as a black citizen. He was a successful writer, publishing articles in national magazines, reaching a wide and diverse audience through Macleans and Cosmopolitan.[9] By the time he wrote his autobiography in Alberta in 1927, Long claimed to be a full-blooded Blackfoot Indian.[10]

Autobiography and fame

Cosmopolitan Book Company commissioned Long's autobiography as a boy's adventure book on Indians. It published Long Lance in 1928, to quick success. In it, Long claimed to have been born a Blackfoot, son of a chief, in Montana's Sweetgrass Hills. He also said that he had been wounded eight times in the Great War and been promoted to the rank of captain.

The popular success of his book and the international press made him a major celebrity. The book became an international bestseller and was praised by literary critics and anthropologists.[11] Long had already been writing and lecturing on the life of Plains Indians. His celebrity gave him more venues and caused him to be taken up as part of the New York party life. More significantly, he was then admitted to the prominent Explorers' Club in New York. The Explorers' Club believed they were admitting their "First Indian."

He received an average price of $100 for his speeches, a good price in those years. He endorsed a sport shoe for the B.F. Goodrich Company. A film magazine, Screenland, said, "Long Lance, one of the few real one-hundred-percent Americans, has had New York right in his pocket."[3]

Impostor revealed

In 1929, Long entered the film world, starring in the silent film The Silent Enemy: An Epic of the American Indian, which purported to show the traditional ways of Ojibwe people, and employed Native Americans as extras and advisors. An Indian advisor to the film crew, Chauncey Yellow Robe, became suspicious of Long and alerted the studio legal advisor. Long could not explain his heritage to their satisfaction, and rumors began to circulate. An investigation revealed that his father had not been a Blackfoot chief, but a school janitor in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.[12] Some neighbors from his home town testified that they thought his background may have included African ancestry, which meant by southern racial standards, he was black.[13] Although the studio did not publicize its investigation, the accusations led many of his socialite acquaintances to abandon Long. Author Irvin S. Cobb, a native of Kentucky active in New York, is reported to have lamented, "We're so ashamed! We entertained a nigger!"[3]

In his Being and Becoming Indian: Biographical Studies of North American Frontiers, late 20th century historian James A. Clifton called Long "a sham" who "assumed the identity of an Indian", "an adopted ethnic identity pure and simple."[3] In her book Real Indians: Identity and the Survival of Native Americans (2003), Eva Marie Garroutte uses the controversy over Long Lance's identity to introduce questions surrounding contested Indian identity and authenticity in United States culture.[3]

Death

After the controversy surrounding his identity, California socialite Anita Baldwin took Long as a bodyguard on her trip to Europe. Because of his behavior, Baldwin abandoned him in New York. For a time, he fell in love with dancer Elisabeth Clapp but refused to marry her. In 1931, he returned to Baldwin. In 1932, Long Lance was found dead in Baldwin's home in Los Angeles, California from a gunshot. His death was ruled a suicide.

Long Lance left his assets to St. Paul’s Indian Residential School in Southern Alberta.[3] Most of his papers were willed to his friend, Canon S.H. Middleton. They were acquired, along with the Middleton papers, by J. Zeiffle, a dealer who sold the papers to the Glenbow Museum in Calgary, Alberta, Canada in 1968.[14]

See also

References

- ↑ Catherine Bainbridge, Linda Ludwick, Christina Fon (September 10, 2009). Reel Injun: On the Trail of the Hollywood Indian (Documentary Film). Catherine Bainbridge, Christina Fon, Linda Ludwick.

- ↑ Alexander D. Gregor, review of Donald B. Smith, Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance: The Glorious Impersonator, Manitoba Library Association, accessed 18 Apr 2009

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Garroutte, Eva Marie (2003). Real Indians: Identity and the Survival of Native America. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22977-0. OCLC 237798744.

- ↑ Melinda Micco, "Tribal Re-Creations: Buffalo Child Long Lance and Black Seminole Narratives", in Re-placing America: Conversations and Contestations, ed. Ruth Hsu, Cynthia Franklin, and Suzanne Kosanke, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i and the East-West Center, 2000, p. 74, accessed 20 Apr 2009

- ↑ "Indians Display Musical Ability". The Carlisle Arrow. Carlisle, Pennsylvania. 9 Jan 1914. p. 4.

- ↑ Karina Joan Vernon, The Black Prairies: History, Subjectivity, Writing, PhD dissertation, University of Victoria, 2008, p.604, accessed 19 Apr 2009

- ↑ Donald B. Smith, Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance: The Glorious Impersonator, Red Deer Press, 1999, p.148

- ↑ Donald B. Smith, Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance: The Glorious Impersonator, Red Deer Press, 1999, p.91

- ↑ Karina Joan Vernon, The Black Prairies: History, Subjectivity, Writing, dissertation, University of Victoria, 2008, pp.67 and 76, accessed 19 Apr 2009

- ↑ Karina Joan Vernon, The Black Prairies: History, Subjectivity, Writing, dissertation, University of Victoria, 2008, p.44, accessed 19 Apr 2009

- ↑ Karina Joan Vernon, The Black Prairies: History, Subjectivity, Writing, PhD dissertation, University of Victoria, 2008, p. 42, accessed 19 Apr 2009

- ↑ Donald B. Smith, Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance: The Glorious Impersonator, Red Deer Press, 1999, pp.243-244

- ↑ Article Candid Slice, Hope Thompson, Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance: NC’s Most Famous Lumbee Native, published 30 June 2016

- ↑ "Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance fonds" Archived July 6, 2010, at the Wayback Machine., Archives, Glenbow Museum, accessed 19 Apr 2009

Further reading

- Donald B. Smith, Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance: The Glorious Impersonator, Red Deer Press, 1999 (Cover has photo of Long)

- Laura Browder, " 'One Hundred Percent American': How a Slave, a Janitor, and a Former Klansmen Escaped Racial Categories by Becoming Indians", in Beyond the Binary: Reconstructing Cultural Identity in a Multicultural Context, ed. Timothy B. Powell, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press (1999)

- Nancy Cook, "The Only Real Indians are Western Ones: Authenticity, Regionalism and Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance, or Sylvester Long" (2004)

- Nancy Cook, "The Scandal of Race: Authenticity, The Silent Enemy and the Problem of Long Lance", in Headline Hollywood: A Century of Film Scandal, ed. Adrienne L. McLean and DAvid A. Cook, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2001

- Melinda Micco, "Tribal Re-Creations: Buffalo Child Long Lance and Black Seminole Narratives", in Re-placing America: Conversations and Contestations, ed. Ruth Hsu, Cynthia Frnklin, and Suzanne Kosanke, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i and the East-West Center, 2000

External links

- "Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance fonds", Archives, Glenbow Museum, Calgary, Alberta

- Watch Long Lance, a National Film Board of Canada documentary