Chernihiv

| Chernihiv · Chernigov Чернігів | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City of regional significance | |||||

|

From top, left to right: Trinity Monastery, Catherine's Church, fortress guns on the Val, Krasna square, Hotel "Desna" building, and view of ancient Chernihiv with Transfiguration, Borys and Hlib Cathedrals and Chernihiv Collegium | |||||

| |||||

| Nickname(s): City of Legends | |||||

Chernihiv · Chernigov Чернігів Location of Chernihiv in Ukraine | |||||

| Coordinates: 51°30′0″N 31°18′0″E / 51.50000°N 31.30000°ECoordinates: 51°30′0″N 31°18′0″E / 51.50000°N 31.30000°E | |||||

| Country |

| ||||

| Oblast | Chernihiv Oblast | ||||

| Municipality | Chernihiv municipality | ||||

| Founded | 907 | ||||

| City Status | 907 | ||||

| Government | |||||

| • Mayor | Vladyslav Atroshenko[1] (Petro Poroshenko Bloc "Solidarity"[1]) | ||||

| Area | |||||

| • Total | 79 km2 (31 sq mi) | ||||

| Elevation | 136 m (446 ft) | ||||

| Population (2015) | |||||

| • Total | 294,727 | ||||

| • Density | 1,547/km2 (4,010/sq mi) | ||||

| Postal code | 14000 | ||||

| Area code(s) | (+380) 462 | ||||

| Vehicle registration | CB / 25 | ||||

| Website | chernigiv-rada.gov.ua | ||||

Chernihiv (also Chernigiv, Chernigov; Ukrainian: Чернігів Ukrainian pronunciation: [t͡ʃɛ̝rˈɲiɦiu̯], Russian: Черни́гов; IPA: [tɕɪrˈnʲiɡəf]),[2] a historic city in northern Ukraine, serves as the administrative center of the Chernihiv Oblast (province), as well as of the surrounding Chernihiv Raion (district) within the oblast. Administratively, it is incorporated as a city of oblast significance. Population: 294,727 (2015 est.)[3]

Geography

Chernihiv stands on the Desna River to the north-north-east of Kiev.

The area was served by Chernihiv Shestovitsa Airport, and during the Cold War it was the site of Chernigov air base.

History

Chernihiv was first mentioned in the Rus'-Byzantine Treaty (907) (as Черниговъ (Chernigov)), but the time of establishment is not known. According to the items uncovered by archaeological excavations of a settlement which included artifacts from the Khazar Khaganate, it seems to have existed at least in the 9th century. Towards the end of the 10th century, the city probably had its own rulers. It was there that the Black Grave, one of the largest and earliest royal mounds in Eastern Europe, was excavated in the 19th century.

In the southern portion of the Kievan Rus' the city was the second by importance and wealth.[4] From the early 11th century it was the seat of powerful Grand Principality of Chernigov, whose rulers at times vied for power with Kievan Grand Princes, and often overthrew them and took the primary seat in Kiev for themselves. The grand principality was the largest in Kievan Rus and included not only the Severian towns but even such remote regions as Murom, Ryazan and Tmutarakan. The golden age of Chernihiv, when the city population peaked at 25,000, lasted until 1239 when the city was sacked by the hordes of Batu Khan, which started a long period of relative obscurity.

The area fell under the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in 1353. The city was burned again by Crimean khan Meñli I Giray in 1482 and 1497 and in the 15th to 17th centuries it changed hands several times between Lithuania, Muscovy (1408–1420 and from 1503), and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (1618–1648), where it was granted Magdeburg rights in 1623 and in 1635 became a seat of Chernihiv Voivodeship. The area's importance increased again in the middle of the 17th century during and after the Khmelnytsky Uprising. In the Hetman State Chernihiv was the city of deployment of Chernihiv Cossack regiment (both a military and territorial unit of the time).

Under the 1667 Treaty of Andrusovo the legal suzerainty of the area was ceded to Tsardom of Russia, with Chernihiv remaining an important center of the autonomous Cossack Hetmanate. With the abolishment of the Hetmanate, the city became an ordinary administrative center of the Russian Empire and a capital of local administrative units. The area in general was ruled by the Governor-General appointed from Saint Petersburg, the imperial capital, and Chernihiv was the capital of local namestnichestvo (province) (from 1782), Malorosiyskaya or Little Russian (from 1797) and Chernigov Governorate (from 1808).

According to the census of 1897, in the city of Chernihiv there were about 11,000 Jews out of the total population of 27,006. Their primary occupations were industrial and commercial. Many tobacco plantations and fruit gardens in the neighborhood were owned by Jews. There were 1,321 Jewish artisans in Chernihiv, including 404 tailors and seamstresses, but the demand for artisan labor was limited to the town. There were 69 Jewish day-laborers, almost exclusively teamsters. But few were engaged in the factories.[5]

During World War II, Chernihiv was occupied by the German Army from 9 September 1941 to 21 September 1943.

Architecture

Chernihiv's architectural monuments chronicle two most flourishing periods in the city's history - those of Kievan Rus' (11th and 12th centuries) and of the Cossack Hetmanate (late 17th and early 18th centuries.)

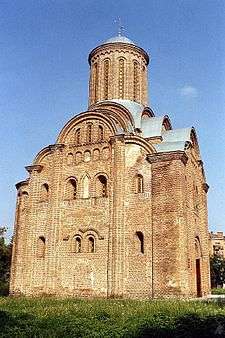

The oldest church in the city and one of the oldest churches in Ukraine is the 5-domed Transfiguration Cathedral, commissioned in the early 1030s by Mstislav the Bold and completed several decades later by his brother, Yaroslav the Wise. The Cathedral of Sts Boris and Gleb, dating from the mid-12th century, was much rebuilt in succeeding periods, before being restored to its original shape in the 20th century. Likewise built in brick, it has a single dome and six pillars. The crowning achievement of Chernihiv masters was the exquisite Pyatnytska Church, constructed at the turn of the 12th and 13th centuries. This graceful building was seriously damaged in the Second World War; its original medieval outlook was reconstructed to a design by Peter Baranovsky.

The earliest residential buildings in the downtown date from the late 17th century, a period when a Cossack regiment was deployed there. Two most representative residences are those of Polkovnyk Lyzohub (1690s) and Polkovnyk Polubutok (18th century). The former mansion, popularly known as the Mazepa House, used to contain the regiment's chancellery. One of the most profusely decorated Cossack structures is undoubtedly the ecclesiastical collegium, surmounted by a bell-tower (1702). The archbishop's residence was constructed nearby in the 1780s. St Catherine Church (1715), with its 5 gilded pear domes, traditional for Ukrainian architecture, is thought to have been intended as a memorial to the regiment's exploits during the storm of Azov in 1696.

Monasteries

All through the most trying periods of its history, Chernihiv retained its ecclesiastical importance as the seat of bishopric or archbishopric. At the outskirts of the modern city lie two ancient cave monasteries, formerly used as the bishops' residences.

The caves of the Eletsky Monastery are said to predate those of the Kiev Pechersk Lavra (Kiev Monastery of the Caves). Its magnificent 6-pillared cathedral was erected at the turn of the 11th and 12th centuries; some traces of its 750-year-old murals may still be seen in the interior. After the domes collapsed in 1611, they were augmented and reconstructed in the Ukrainian baroque style. The wall, monastic cells, and bell-tower all date from the 17th century. The nearby mother superior's house is thought to be the oldest residential building in the Left-Bank Ukraine. The cloister's holiest icon used to be that of Theotokos, who made her epiphany to Svyatoslav of Chernigov on 6 February 1060. The icon, called Eletskaya after the fir wood it was painted upon, was taken to Moscow by Svyatoslav's descendants, the Baryatinsky family, in 1579.

The nearby cave monastery of Saint Elijah and the Holy Trinity features a small eponymous church, which was constructed 800 years ago. The roomy Trinity cathedral, one of the most imposing monuments of the Cossack baroque, was erected between 1679 and 1689. Its refectory, with the adjoining church of Presentation to the Temple, was finished by 1679. There are also the 17th-century towered walls, monastic cells, and the five-tiered belfry from the 1780s.

Other historic abbeys may be visited in the vicinity of Chernihiv; those in Kozelets and Hustynya contain superb samples of Ukrainian national architecture.

Climate

Chernihiv has a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfb) with cold, cloudy and snowy winters, and warm, sunny summers. The average annual temperature for Chernihiv is 7.0 °C (44.6 °F), ranging from a low of −5.6 °C (21.9 °F) in January to a high of 19.5 °C (67.1 °F) in July. Precipitation is well distributed throughout the year though precipitation is higher during the summer months and lower during the winter months. The record high was 39.0 °C (102.2 °F) and the record low was −36.0 °C (−32.8 °F).

| Climate data for Chernihiv | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 9.6 (49.3) |

16.2 (61.2) |

22.3 (72.1) |

28.9 (84) |

33.5 (92.3) |

39.0 (102.2) |

38.9 (102) |

38.0 (100.4) |

32.6 (90.7) |

27.8 (82) |

18.4 (65.1) |

14.0 (57.2) |

39.0 (102.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −3.1 (26.4) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

3.8 (38.8) |

13.0 (55.4) |

20.0 (68) |

23.3 (73.9) |

25.2 (77.4) |

24.3 (75.7) |

18.5 (65.3) |

11.5 (52.7) |

3.8 (38.8) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

11.4 (52.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −5.6 (21.9) |

−4.9 (23.2) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

8.0 (46.4) |

14.4 (57.9) |

17.8 (64) |

19.5 (67.1) |

18.4 (65.1) |

12.9 (55.2) |

6.9 (44.4) |

1.0 (33.8) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

7.08 (44.72) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −8.7 (16.3) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

3.3 (37.9) |

8.9 (48) |

12.4 (54.3) |

14.2 (57.6) |

13.1 (55.6) |

8.0 (46.4) |

2.9 (37.2) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

−6.1 (21) |

2.9 (37.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −36 (−33) |

−33.9 (−29) |

−29.9 (−21.8) |

−13.9 (7) |

−2.2 (28) |

1.1 (34) |

3.9 (39) |

2.0 (35.6) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

−10.8 (12.6) |

−23.5 (−10.3) |

−28 (−18) |

−36 (−33) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 41.2 (1.622) |

35.1 (1.382) |

35.5 (1.398) |

44.4 (1.748) |

50.8 (2) |

82.9 (3.264) |

83.8 (3.299) |

66.2 (2.606) |

58.4 (2.299) |

38.8 (1.528) |

45.6 (1.795) |

45.5 (1.791) |

628.2 (24.732) |

| Average precipitation days | 20.4 | 17.9 | 14.6 | 11.1 | 10.2 | 10.4 | 8.2 | 8.6 | 9.5 | 11.4 | 15.8 | 19.7 | 157.8 |

| Average snowy days | 16 | 13 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 15 | 64 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 85.5 | 81.6 | 75.1 | 64.0 | 63.3 | 66.7 | 68.6 | 68.4 | 74.8 | 80.4 | 87.3 | 88.0 | 75.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 49.6 | 70.0 | 127.1 | 201.0 | 279.0 | 285.0 | 303.8 | 275.9 | 183.0 | 120.9 | 36.0 | 34.1 | 1,965.4 |

| Source #1: Climatebase.ru[6] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Weatherbase[7] | |||||||||||||

Gallery

Pretty square (Krasna ploshcha) and Shevchenko Theatre

Pretty square (Krasna ploshcha) and Shevchenko Theatre- Opera and Drama Theatre

- Shchors cinema in Chernihiv

- Hotel Desna

Chernihiv City Council

Chernihiv City Council Museum of history, former Governor's House

Museum of history, former Governor's House- Mykhailo Kotsiubynskyi Museum

- Tarnovsky Museum of antiquities

Chernihiv architecture

Chernihiv architecture Old and modern buildings

Old and modern buildings New apartment block

New apartment block City hospital

City hospital Chernihiv philharmony

Chernihiv philharmony Palace of celebrations

Palace of celebrations Chernihiv Yuri Gagarin Stadium

Chernihiv Yuri Gagarin Stadium

Famous people from Chernihiv

- Jacob Tamarkin, Russian-American mathematician born in Chernihiv

- Anatoly Rybakov, Russian writer

- Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, Soviet Bolshevik leader and diplomat

- Vadim Pruzhanov, keyboardist for the Extreme Power Metal band DragonForce

- Giennadij Jerszow, Polish-Ukrainian sculptor born in Chernihiv

- Eduard Weitz (born 1946), Israeli Olympic weightlifter

- Andriy Yarmolenko, Ukrainian footballer raised in Chernihiv who plays for Dynamo Kiev

International relations

Twin towns - Sister cities

Chernihiv is currently twinned with:

Gomel, Belarus

Gomel, Belarus Memmingen, Bavaria, Germany

Memmingen, Bavaria, Germany Tarnobrzeg, Poland [8]

Tarnobrzeg, Poland [8]-

Petah Tikva, Israel

Petah Tikva, Israel -

Gabrovo, Bulgaria

Gabrovo, Bulgaria -

Hradec Králové, Czech Republic

Hradec Králové, Czech Republic -

Ogre, Latvia

Ogre, Latvia -

Prilep, Macedonia

Prilep, Macedonia

References

Bibliography

- Logvin, G.N. (Г. Н. Логвин) (1965). Chernigov, Novgorod-Seversky, Glukhov, Putivl (Чернигов, Новгород-Северский, Глухов, Путивль) (in Russian). Moscow.

- Pyotr Rappoport (П. А. Раппопорт) (1993). Ancient Russian Architecture (Древнерусская архитектура) (in Russian). Saint-Petersburg.

- Martin Dimnik (2003). The Dynasty of Chernigov, 1146-1246. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-82442-7.

- (1972) Icтopia мicт i ciл Укpaїнcькoї CCP - Чернiгiвськa область (History of Towns and Villages of the Ukrainian SSR - Chernihiv Oblast), Kiev. (in Ukrainian)

Notes

- 1 2 Poroshenko Bloc's Atroshenko wins Chernihiv mayoral election – Central Election Commission, Interfax-Ukraine (18 November 2015)

- ↑ Other English renditions of Чернигов include Tchernigov, Tschernigow, Tschernigov, Chernigiv and Chernigow.

- ↑ "Чисельність наявного населення України (Actual population of Ukraine)" (PDF) (in Ukrainian). State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ↑ Nasledie Svyatoy Rusi URL accessed on January 12, 2006

- ↑ jewishencyclopedia.com Copy from 12-volume Jewish Encyclopedia, which was originally published between 1901-1906.

- ↑ "Climate Data for Chernihiv, Ukraine 1949-2011". Climatebase. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- ↑ "Weatherbase: Historical Weather for Chernihiv, Ukraine". Weatherbase. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- ↑ "Tarnobrzeg Official Website - Partner Cities".

(in Polish) © 1999-2008 Urząd Miasta Tarnobrzeg. Archived from the original on 2007-12-18. Retrieved 2008-10-23.

(in Polish) © 1999-2008 Urząd Miasta Tarnobrzeg. Archived from the original on 2007-12-18. Retrieved 2008-10-23.

External links

- Chernihiv City Portal

- chernigiv-rada.gov.ua — Official webportal of the Chernihiv City Rada (in Ukrainian)/(in English)

- Chernihiv guide

- Chernihiv in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine

- chernihiv-oblast.gov.ua — Invest in Chernihiv Oblast

- Chernihiv Map — Map of Chernihiv City

- Chernihiv board — Chernihiv regional board

- Construction site of Chernigov — Construction site of Chernihiv

- "Chernigov-Gethsemane" Icon of the Mother of God. Russian Orthodox Cathedral of St. John the Baptist, Washington DC. (ROCOR).

- Chernihiv Sketch Map — Sketch Map of Chernihiv

- Chernihiv souvenirs — Chernihiv Gifts and Souvenirs

- History of Jewish Community in Chernigov

- The murder of the Jews of Chernihiv during World War II, at Yad Vashem website.