Chemotaxis

Chemotaxis (from chemo- + taxis) is the movement of an organism in response to a chemical stimulus.[1] Somatic cells, bacteria, and other single-cell or multicellular organisms direct their movements according to certain chemicals in their environment. This is important for bacteria to find food (e.g., glucose) by swimming toward the highest concentration of food molecules, or to flee from poisons (e.g., phenol). In multicellular organisms, chemotaxis is critical to early development (e.g., movement of sperm towards the egg during fertilization) and subsequent phases of development (e.g., migration of neurons or lymphocytes) as well as in normal function. In addition, it has been recognized that mechanisms that allow chemotaxis in animals can be subverted during cancer metastasis.

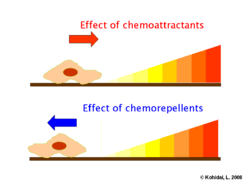

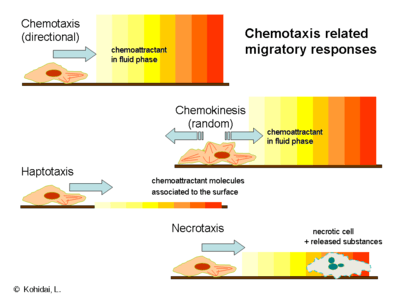

Positive chemotaxis occurs if the movement is toward a higher concentration of the chemical in question; negative chemotaxis if the movement is in the opposite direction. Chemically prompted kinesis (randomly directed or nondirectional) can be called chemokinesis.

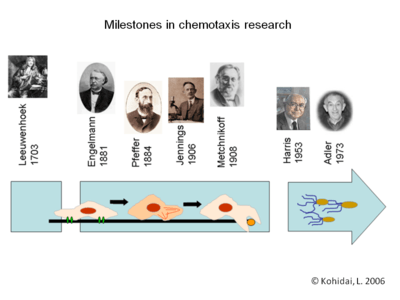

History of chemotaxis research

Although migration of cells was detected from the early days of the development of microscopy by Leeuwenhoek, a Cal-tech lecture regarding chemotaxis propounds that 'erudite description of chemotaxis was only first made by T. W. Engelmann (1881) and W. F. Pfeffer (1884) in bacteria, and H. S. Jennings (1906) in ciliates'.[2] The Nobel Prize laureate I. Metchnikoff also contributed to the study of the field during 1882 to 1886, with investigations of the process as an initial step of phagocytosis.[3] The significance of chemotaxis in biology and clinical pathology was widely accepted in the 1930s, and the most fundamental definitions underlying the phenomenon were drafted by this time. The most important aspects in quality control of chemotaxis assays were described by H. Harris in the 1950s.[4] In the 1960s and 1970s, the revolution of modern cell biology and biochemistry provided a series of novel techniques that became available to investigate the migratory responder cells and subcellular fractions responsible for chemotactic activity.[5] The availability of this technology led to the discovery of C5a, a major chemotactic factor involved in acute inflammation. The pioneering works of J. Adler represented a significant turning point in understanding the whole process of intracellular signal transduction of bacteria.[6]

Continuing research emphasis

Research on cell migration applies complementary techniques, classical and modern. The field of studies in chemotaxis contributes both basic research and applied science. As such, in the last 20–25 years, there has been an increase in the number of publications focusing on chemotaxis, and publications written in genetics, biochemistry, cell-physiology, pathology and clinical sciences, etc. also incorporate data on cell migration and chemotaxis. Of the various ares of research into diverse, known taxis phenomena—e.g., thermotaxis, geotaxis, phototaxis), etc.—chemotaxis research contributes a significant proportion overall, underscoring the fundamental importance of chemotaxis research in biology and medicine.

Chemoattractants and chemorepellents

Chemoattractants and chemorepellents are inorganic or organic substances possessing chemotaxis-inducer effect in motile cells. Effects of chemoattractants are elicited via described or hypothetic chemotaxis receptors, the chemoattractant moiety of a ligand is target cell specific and concentration dependent. Most frequently investigated chemoattractants are formyl peptides and chemokines. Responses to chemorepellents result in axial swimming and they are considered a basic motile phenomena in bacteria. The most frequently investigated chemorepellents are inorganic salts, amino acids, and some chemokines.

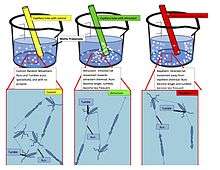

Bacterial chemotaxis—general characteristics

.png)

Some bacteria, such as E. coli, have several flagella per cell (4–10 typically). These can rotate in two ways:

- Counter-clockwise rotation aligns the flagella into a single rotating bundle, causing the bacterium to swim in a straight line; and

- Clockwise rotation breaks the flagella bundle apart such that each flagellum points in a different direction, causing the bacterium to tumble in place.

The directions of rotation are given for an observer outside the cell looking down the flagella toward the cell.

Behavior

The overall movement of a bacterium is the result of alternating tumble and swim phases. If one watches a bacterium swimming in a uniform environment, its movement will look like a random walk with relatively straight swims interrupted by random tumbles that reorient the bacterium. Bacteria such as E. coli are unable to choose the direction in which they swim, and are unable to swim in a straight line for more than a few seconds due to rotational diffusion; in other words, bacteria "forget" the direction in which they are going. By repeatedly evaluating their course, and adjusting if they are moving in the wrong direction, bacteria can direct their motion to find favorable locations with high concentrations of attractants (usually food) and avoid repellents (usually poisons).

In the presence of a chemical gradient bacteria will chemotax, or direct their overall motion based on the gradient. If the bacterium senses that it is moving in the correct direction (toward attractant/away from repellent), it will keep swimming in a straight line for a longer time before tumbling; however, if it is moving in the wrong direction, it will tumble sooner and try a new direction at random. In other words, bacteria like E. coli use temporal sensing to decide whether their situation is improving or not, and in this way, find the location with the highest concentration of attractant (usually the source) quite well. Even under very high concentrations, it can still distinguish very small differences in concentration, and fleeing from a repellent works with the same efficiency.

This biased random walk is a result of simply choosing between two methods of random movement; namely tumbling and straight swimming.[7] In fact, chemotactic responses such as forgetting direction and choosing movements resemble the decision-making abilities of higher life-forms with brains that process sensory data.

The helical nature of the individual flagellar filament is critical for this movement to occur, and the protein that makes up the flagellar filament, flagellin, is quite similar among all flagellated bacteria. Vertebrates seem to have taken advantage of this fact by possessing an immune receptor (TLR5) designed to recognize this conserved protein.

As in many instances in biology, there are bacteria that do not follow this rule. Many bacteria, such as Vibrio, are monoflagellated and have a single flagellum at one pole of the cell. Their method of chemotaxis is different. Others possess a single flagellum that is kept inside the cell wall. These bacteria move by spinning the whole cell, which is shaped like a corkscrew.[8]

Signal transduction

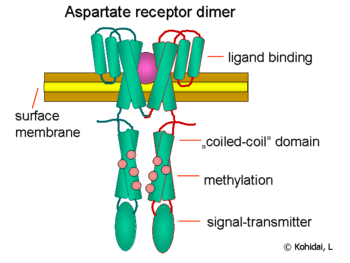

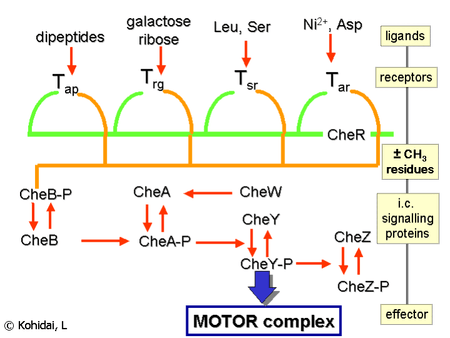

Chemical gradients are sensed through multiple transmembrane receptors, called methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (MCPs), which vary in the molecules that they detect. These receptors may bind attractants or repellents directly or indirectly through interaction with proteins of periplasmatic space. The signals from these receptors are transmitted across the plasma membrane into the cytosol, where Che proteins are activated. The Che proteins alter the tumbling frequency, and alter the receptors.

Flagellum regulation

The proteins CheW and CheA bind to the receptor. The absence of receptor activation results in autophosphorylation in the histidine kinase, CheA, at a single highly conserved histidine residue.[9] CheA, in turn, transfers phosphoryl groups to conserved aspartate residues in the response regulators CheB and CheY; CheA is a histidine kinase and it does not actively transfer the phosphoryl group, rather, the response regulator CheB takes the phosphoryl group from CheA. This mechanism of signal transduction is called a two-component system, and it is a common form of signal transduction in bacteria. CheY induces tumbling by interacting with the flagellar switch protein FliM, inducing a change from counter-clockwise to clockwise rotation of the flagellum. Change in the rotation state of a single flagellum can disrupt the entire flagella bundle and cause a tumble.

Receptor regulation

CheB, when activated by CheA, acts as a methylesterase, removing methyl groups from glutamate residues on the cytosolic side of the receptor; it works antagonistically with CheR, a methyltransferase, which adds methyl residues to the same glutamate residues. If the level of an attractant remains high, the level of phosphorylation of CheA (and, therefore, CheY and CheB) will remain low, the cell will swim smoothly, and the level of methylation of the MCPs will increase (because CheB-P is not present to demethylate). The MCPs no longer respond to the attractant when they are fully methylated; therefore, even though the level of attractant might remain high, the level of CheA-P (and CheB-P) increases and the cell begins to tumble. The MCPs can be demethylated by CheB-P, and, when this happens, the receptors can once again respond to attractants. The situation is the opposite with regard to repellents: fully methylated MCPs respond best to repellents, while least-methylated MCPs respond worst to repellents. This regulation allows the bacterium to 'remember' chemical concentrations from the recent past, a few seconds, and compare them to those it is currently experiencing, thus 'know' whether it is traveling up or down a gradient. Although the methylation system accounts for the wide range of sensitivity[10] that bacteria have to chemical gradients, other mechanisms are involved in increasing the absolute value of the sensitivity on a given background. Well-established examples are the ultra-sensitive response of the motor to the CheY-P signal, and the clustering of chemoreceptors.[11][12] [

Eukaryotic chemotaxis

The mechanism that eukaryotic cells employ is quite different from that in bacteria; however, sensing of chemical gradients is still a crucial step in the process.[13] Due to their size, prokaryotes cannot detect effective concentration gradients; therefore, these cells scan and evaluate their environment by a constant swimming (consecutive steps of straight swims and tumbles). In contrast, the size of eukaryotic cells allows for the possibility of detecting gradients, which results in a dynamic and polarized distribution of receptors; induction of these receptors by chemoattractants or chemorepellents results in migration towards or away from the chemotactic substance.

Levels of receptors, intracellular signalling pathways and the effector mechanisms all represent diverse, eukaryotic-type components. In eukaryotic unicellular cells, amoeboid movement and cilium or the eukaryotic flagellum are the main effectors (e.g., Amoeba or Tetrahymena).[14][15] Some eukaryotic cells of higher vertebrate origin, such as immune cells also move to where they need to be. Besides immune competent cells (granulocyte, monocyte, lymphocyte) a large group of cells—considered previously to be fixed into tissues—are also motile in special physiological (e.g., mast cell, fibroblast, endothelial cells) or pathological conditions (e.g., metastases). Chemotaxis has high significance in the early phases of embryogenesis as development of germ layers is guided by gradients of signal molecules.

Motility

Unlike motility in bacterial chemotaxis, the mechanism by which eukaryotic cells physically move is unclear. There appear to be mechanisms by which an external chemotactic gradient is sensed and turned into an intracellular PIP3 gradient, which results in a gradient and the activation of a signaling pathway, culminating in the polymerisation of actin filaments. The growing distal end of actin filaments develops connections with the internal surface of the plasma membrane via different sets of peptides and results in the formation of anteriorpseudopods and posterior uropods. Cilia of eukaryotic cells can also produce chemotaxis; in this case, it is mainly a Ca2+-dependent induction of the microtubular system of the basal body and the beat of the 9+2 microtubules within cilia. The orchestrated beating of hundreds of cilia is synchronized by a submembranous system built between basal bodies. The details of the signaling pathways are still not totally clear.

Chemotaxis related migratory responses

Although chemotaxis is the most frequently studied form of migration there are several other forms of locomotion in the cellular level.

- Chemokinesis is also induced by molecules of the liquid phase of the surrounding environment; however, the response elicited is a not vectorial, random taxis. Neither amplitude nor frequency of motion has characteristic, directional components, as this behaviour provides more scanning of the environment than migration between two distinct points.

- In haptotaxis the gradient of the chemoattractant is expressed or bound on a surface, in contrast to the classical model of chemotaxis, in which the gradient develops in a soluble fluid. The most common biologically active haptotactic surface is the extracellular matrix (ECM); the presence of bound ligands is responsible for induction of transendothelial migration and angiogenesis.

- Necrotaxis embodies a special type of chemotaxis when the chemoattractant molecules are released from necrotic or apoptotic cells. Depending on the chemical character of released substances, necrotaxis can accumulate or repel cells, which underlines the pathophysiological significance of this phenomenon.

Receptors

In general, eukaryotic cells sense the presence of chemotactic stimuli through the use of 7-transmembrane (or serpentine) heterotrimeric G-protein-coupled receptors, a class representing a significant portion of the genome. Some members of this gene superfamily are used in eyesight (rhodopsins) as well as in olfaction (smelling). The main classes of chemotaxis receptors are triggered by:

- formyl peptides - formyl peptide receptors (FPR),

- chemokines - chemokine receptors (CCR or CXCR), and

- leukotrienes - leukotriene receptors (BLT).

However, induction of a wide set of membrane receptors (e.g., amino acids, insulin, vasoactive peptides) also elicit migration of the cell.

Chemotactic selection

While some chemotaxis receptors are expressed in the surface membrane with long-term characteristics, as they are determined genetically, others have short-term dynamics, as they are assembled ad hoc in the presence of the ligand. The diverse features of the chemotaxis receptors and ligands allows for the possibility of selecting chemotactic responder cells with a simple chemotaxis assay. By chemotactic selection, we can determine whether a still-uncharacterized molecule acts via the long- or the short-term receptor pathway. The term chemotactic selection is also used to designate a technique that separates eukaryotic or prokaryotic cells according to their chemotactic responsiveness to selector ligands.[16]

Chemotactic ligands

The number of molecules capable of eliciting chemotactic responses is relatively high, and we can distinguish primary and secondary chemotactic molecules. The main groups of the primary ligands are as follows:

- Formyl peptides are di-, tri-, tetrapeptides of bacterial origin, formylated on the N-terminus of the peptide. They are released from bacteria in vivo or after decomposition of the cell[ a typical member of this group is the N-formylmethionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (abbreviated fMLF or fMLP). Bacterial fMLF is a key component of inflammation has characteristic chemoattractant effects in neutrophil granulocytes and monocytes. The chemotactic factor ligands and receptors related to formyl peptides are summarized in the related article, Formyl peptide receptors.

- Complement 3a (C3a) and complement 5a (C5a) are intermediate products of the complement cascade. Their synthesis is joined to the three alternative pathways (classical, lectin-dependent, and alternative) of complement activation by a convertase enzyme. The main target cells of these derivatives are neutrophil granulocytes and monocytes as well.

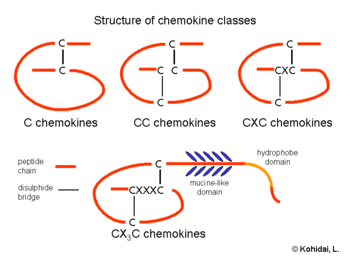

- Chemokines belong to a special class of cytokines; not only do their groups (C, CC, CXC, CX3C chemokines) represent structurally related molecules with a special arrangement of disulfide bridges but also their target cell specificity is diverse. CC chemokines act on monocytes (e.g., RANTES), and CXC chemokines are neutrophil granulocyte-specific (e.g., IL-8). Investigations of the three-dimensional structures of chemokines provided evidence that a characteristic composition of beta-sheets and an alpha helix provides expression of sequences required for interaction with the chemokine receptors. Formation of dimers and their increased biological activity was demonstrated by crystallography of several chemokines, e.g. IL-8.

- Metabolites of polyunsaturated fatty acids

- Leukotrienes are eicosanoid lipid mediators made by the metabolism of arachidonic acid by ALOX5 (also termed 5-lipoxygenase). Their most prominent member with chemotactic factor activity is leukotriene B4, which elicits adhesion, chemotaxis, and aggregation of leukocytes. The chemoattractant action of LTB4 is induced via either of two G protein–coupled receptors, BLT1 and BLT2, which are highly expressed in cells involved in inflammation and allergy.[17]

- The family of 5-Hydroxyicosatetraenoic acid eicosanoids are arachidonic acid metabolites also formed by ALOX5. Three members of the family form naturally and have prominent chemotactic activity. These, listed in order of decreasing potency, are: 5-oxo-eicosatetraenoic acid, 5-oxo-15-hydroxy-eicosatetraenoic acid, and 5-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid. This family of agonists stimulates chemotactic responses in human eosinophils, neutrophils, and monocytes by binding to the Oxoeicosanoid receptor 1, which like the receptors for leukotriene B4, is a G protein-coupled receptor.[17]

- 5-hydroxyeicosatrieonic acid and 5-oxoeicosatrienoic acid are metabolites of Mead acid (5Z,8Z,11Z-eicosatrirenoid acid); they stimulate leukocyte chemotaxis through the oxoeicosanoid receptor 1[18] with 5-oxoeicosatrienoic acid being as potent as its arachidonic acid-derived analog, 5-oxo-eicosatetraenoic acid, in stimulating human blood eosinophil and neutrophil chemotaxis.[17]

- 12-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid is an eicosanoid metabolite of arachidonic acid made by ALOX12 which stimulates leukocyte chemotaxis through the leukotriene B4 receptor, BLT2.[17]

- Prostaglandin D2 is an eicosanoid metabolite of arachidononic acid made by cyclooxygenase 1 or cyclooxygenase 2 that stimulates chemotaxis through the Prostaglandin DP2 receptor. It elicits chemotactic responses in eosinophils, basophils, and T helper cells of the Th2 subtype.[19]

- 12-Hydroxyheptadecatrienoic acid is a non-eicosanoid metabolite of arachidonic acid made by cyclooxygenase 1 or cyclooxygenase 2 that stimulates leukocyte chemataxis though the leukotriene B4 receptor, BLT2.[20]

- 15-oxo-eicosatetraenoic acid is an eicosanoid metabolite of arachidonic acid made my ALOX15; it has weak chemotactic activity for human monocytes (sees 15-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid#15-oxo-ETE).[21] The receptor or other mechanism by which this metabolite stimulates chemotaxis has not been elucidated.

Chemotactic range fitting

Chemotactic responses elicited by the ligand-receptor interactions are, in general, distinguished upon the optimal effective concentration(s) of the ligand. Nevertheless, correlation of the amplitude elicited and ratio of the responder cells compared to the total number are also characteristic features of the chemotactic signaling. Investigations of ligand families (e.g., amino acids or oligo peptides) proved that there is a fitting of ranges (amplitudes; number of responder cells) and chemotactic activities: Chemoattractant moiety is accompanied by wide ranges, whereas chemorepellent character by narrow ranges.

Clinical significance

A changed migratory potential of cells has relatively high importance in the development of several clinical symptoms and syndromes. Altered chemotactic activity of extracellular (e.g., Escherichia coli) or intracellular (e.g., Listeria monocytogenes) pathogens itself represents a significant clinical target. Modification of endogenous chemotactic ability of these microorganisms by pharmaceutical agents can decrease or inhibit the ratio of infections or spreading of infectious diseases. Apart from infections, there are some other diseases wherein impaired chemotaxis is the primary etiological factor, as in Chédiak–Higashi syndrome, where giant intracellular vesicles inhibit normal migration of cells.

| Type of disease | Chemotaxis increased | Chemotaxis decreased |

|---|---|---|

| Infections | inflammations | AIDS, Brucellosis |

| Chemotaxis results the disease | — | Chédiak–Higashi syndrome, Kartagener syndrome |

| Chemotaxis is affected | atherosclerosis, arthritis, periodontitis, psoriasis, reperfusion injury, metastatic tumors | multiple sclerosis, Hodgkin disease, male infertility |

| Intoxications | asbestos, benzpyrene | Hg and Cr salts, ozone |

Mathematical models

Several mathematical models of chemotaxis were developed depending on the type of

- migration (e.g., basic differences of bacterial swimming, movement of unicellular eukaryotes with cilia/flagellum and amoeboid migration)

- physico-chemical characteristics of the chemicals (e.g., diffusion) working as ligands

- biological characteristics of the ligands (attractant, neutral, and repellent molecules)

- assay systems applied to evaluate chemotaxis (see incubation times, development, and stability of concentration gradients)

- other environmental effects possessing direct or indirect influence on the migration (lighting, temperature, magnetic fields, etc.)

Although interactions of the factors listed above make the behavior of the solutions of mathematical models of chemotaxis rather complex, it is possible to describe the basic phenomenon of chemotaxis-driven motion in a straightforward way. Indeed, let us denote with the spatially non-uniform concentration of the chemo-attractant and with its gradient. Then the chemotactic cellular flow (also called current) that is generated by the chemotaxis is linked to the above gradient by the law: , where is the spatial density of the cells and is the so-called ’Chemotactic coefficient’. However, note that in many cases is not constant: It is, instead, a decreasing function of the concentration of the chemo-attractant : .

Spatial ecology of soil microorganisms is a function of their chemotactic sensitivities towards substrate and fellow organisms.[22] The chemotactic behavior of the bacteria was proven to lead to non-trivial population patterns even in the absence of environmental heterogeneities. The presence of structural pore scale heterogeneities has an extra impact on the emerging bacterial patterns.

Measurement of chemotaxis

A wide range of techniques is available to evaluate chemotactic activity of cells or the chemoattractant and chemorepellent character of ligands. The basic requirements of the measurement are as follows:

- concentration gradients can develop relatively quickly and persist for a long time in the system

- chemotactic and chemokinetic activities are distinguished

- migration of cells is free toward and away on the axis of the concentration gradient

- detected responses are the results of active migration of cells

Despite the fact that an ideal chemotaxis assay is still not available, there are several protocols and pieces of equipment that offer good correspondence with the conditions described above. The most commonly used are summarised in the table below:

| Type of assay | Agar-plate assays | Two-chamber assays | Others |

|---|---|---|---|

| Examples |

|

|

|

Artificial chemotactic systems

Chemical robots that use artificial chemotaxis to navigate autonomously have been designed. Applications include targeted delivery of drugs in the body.[23]

Awards recognising discoveries in chemotaxis

In 1980, Julius Adler of the University of Wisconsin–Madison was awarded the Selman A. Waksman Award in Microbiology of the National Academy of Sciences for his work on chemotaxis and motility in bacteria.[24] In 1996, he won the William C. Rose Award of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.[25] On November 3, 2006, Dennis Bray of University of Cambridge was awarded the Microsoft Award for his work on chemotaxis on E. coli.[26][27]

See also

References

- ↑

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Chemotaxis". Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 77.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Chemotaxis". Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 77. - ↑ Chemotaxis Lecture. Uploaded in 2007. available at: http://www.rpgroup.caltech.edu/courses/aph161/2007/lectures/ChemotaxisLecture.pdf (Last inspected: 15/04/17)

- ↑ Élie Metchnikoff". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

- ↑ Keller-Segel Models for Chemotaxis. 2012. available at: http://www.isn.ucsd.edu/courses/Beng221/problems/2012/BENG221_Project%20-%20Roberts%20Chung%20Yu%20Li.pdf (Last inspected by April 2017)

- ↑ Snyderman R, Gewurz H, Mergenhagen SE (1968). "Interactions of the Complement System with Endotoxic Lipopolysaccharide. Generation of a Factor Chemotactic for Polymorphonuclear L eukocytes". J. Exp. Med. 128 (2; August): 259–275.

- ↑ Adler J & Tso, W-W (1974). "Decision-Making in Bacteria: Chemotactic Response of Escherichia Coli to Conflicting Stimuli". Science. 184 (4143): 1292–1294. Bibcode:1974Sci...184.1292A. PMID 4598187. doi:10.1126/science.184.4143.1292.

- ↑ Macnab RM, Koshland DE (September 1972). "The gradient-sensing mechanism in bacterial chemotaxis". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 69 (9): 2509–12. Bibcode:1972PNAS...69.2509M. PMC 426976

. PMID 4560688. doi:10.1073/pnas.69.9.2509.

. PMID 4560688. doi:10.1073/pnas.69.9.2509. - ↑ Berg, Howard C. (2003). E. coli in motion. New York, NY: Springer. ISBN 0387008888.

- ↑ ToxCafe (2 June 2011). "Chemotaxis". Retrieved March 23, 2017 – via YouTube.

- ↑ Mello BA & Tu Y (2007). "Effects of Adaptation in Maintaining High Sensitivity Over a Wide Range of Backgrounds for Escherichia coli Chemotaxis". Biophysical Journal. 92 (7): 2329–2337. Bibcode:2007BpJ....92.2329M. PMC 1864821

. PMID 17208965. doi:10.1529/biophysj.106.097808.

. PMID 17208965. doi:10.1529/biophysj.106.097808. - ↑ Cluzel P, Surette M & Leibler, S (2000). "An Ultrasensitive Bacterial Motor Revealed by Monitoring Signaling Proteins in Single Cells". Science. 287 (5458): 1652–1655. Bibcode:2000Sci...287.1652C. PMID 10698740. doi:10.1126/science.287.5458.1652.

- ↑ Sourjik V & Tso WW (2004). "Receptor clustering and signal processing in E. coli chemotaxis". Trends in Microbiology. 12 (12): 569–576. PMID 15539117. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2004.10.003.

- ↑ Köhidai, Laszio (2016), "Chemotaxis as an Expression of Communication of Tetrahymena", in Witzany, G; Nowacki, M, Biocommunication of Ciliates, pp. 65–82, ISBN 978-3-319-32211-7, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-32211-7_5

- ↑ Bagorda A & Parent CA (2008). "Eukaryotic chemotaxis at a glance". J. Cell Science. 121 (Pt 16): 2621–4. PMID 18685153. doi:10.1242/jcs.018077.

- ↑ Laszlo Kohidai (1999). "Chemotaxis: the proper physiological response to evaluate phylogeny of signal molecules". Acta Biol Hung. 50 (4): 375–94. PMID 10735174.

- ↑ Laszlo Kohidai and Gyorgy Csaba (1988). "Chemotaxis and chemotactic selection induced with cytokines (IL-8, RANTES and TNF alpha) in the unicellular Tetrahymena pyriformis.". Cytokine. 10 (7): 481–6. PMID 9702410. doi:10.1006/cyto.1997.0328.

- 1 2 3 4 Powell WS, Rokach J (2015). "Biosynthesis, biological effects, and receptors of hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETEs) and oxoeicosatetraenoic acids (oxo-ETEs) derived from arachidonic acid". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1851 (4): 340–55. PMID 25449650. doi:10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.10.008. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- ↑ Powell WS, Rokach J (2013). "The eosinophil chemoattractant 5-oxo-ETE and the OXE receptor". Prog. Lipid Res. 52 (4; October): 651–65. doi:10.1016/j.plipres.2013.09.001. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- ↑ Matsuoka T, Narumiya S (2007). "Prostaglandin receptor signaling in disease". The Scientific World Journal. 7: 1329–47. PMID 17767353. doi:10.1100/tsw.2007.182.

- ↑ Yokomizo T (2015). "Two distinct leukotriene B4 receptors, BLT1 and BLT2". Journal of Biochemistry. 157 (2): 65–71. PMID 25480980. doi:10.1093/jb/mvu078.

- ↑ Sozzani, S; Zhou, D; Locati, M; Bernasconi, S; Luini, W; Mantovani, A; O'Flaherty, J. T. (1996). "Stimulating properties of 5-oxo-eicosanoids for human monocytes: Synergism with monocyte chemotactic protein-1 and -3". Journal of Immunology. 157 (10): 4664–71. PMID 8906847.

- ↑ Gharasoo, Mehdi; Centler, Florian; Fetzer, Ingo; Thullner, Martin (2014). "How the chemotactic characteristics of bacteria can determine their population patterns". Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 69: 346. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.11.019.

- ↑ Lagzi, István (2013). "Chemical Robotics—Chemotactic Drug Carriers". Central European Journal of Medicine. 8 (4): 377–382. doi:10.2478/s11536-012-0130-9.

- ↑ National Academy of Sciences. "About the Selman A. Waksman Award in Microbiology". National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ↑ American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. "WILLIAM C. ROSE AWARD". American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ↑ U.K. Professor Captures Inaugural European Science Award, By Rob Knies, News - Microsoft Research, retrieved November 6, 2006 Archived September 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Computer bug study wins top prize, 3 November 2006, BBC NEWS, retrieved November 6, 2006

Further reading

- Rao CV, Kirby JR & Arkin AP (2004). [journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.0020049 "Design and Diversity in Bacterial Chemotaxis: A Comparative Study in Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis"] Check

|url=value (help). PLoS Biol. 2 (2): e49. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020049. - Berg, Howard C. (1993). Random walks in biology (Expanded, rev. ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press. ISBN 9780691000640.

- Eisenbach, Micheal (2004). Lengeler, Joseph W., ed. Chemotaxis. London: Imperial College Press. ISBN 9781860944130.

- Bacterial Chemotaxis Depends on a Two-Component Signaling Pathway Activated by Histidine-Kinase-associated Receptors, Molecular Biology of the Cell 4th Edition © 2002 by Bruce Alberts, Alexander Johnson, Julian Lewis, Martin Raff, Keith Roberts, and Peter Walter.

- Figure 15-69. The two-component signaling pathway that enables chemotaxis receptors to control the flagellar motor during bacterial chemotaxis, Molecular Biology of the Cell 4th Edition © 2002 by Bruce Alberts, Alexander Johnson, Julian Lewis, Martin Raff, Keith Roberts, and Peter Walter.

- Global Existence for Chemotaxis with Finite Sampling Radius

External links

| Wikibooks has more on the topic of: Chemotaxis |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chemotaxis. |

- Chemotaxis

- Neutrophil Chemotaxis

- Cell Migration Gateway

- Downloadable Matlab chemotaxis simulator

- Bacterial Chemotaxis Interactive Simulator (web-app)