Chemistry of biofilm prevention

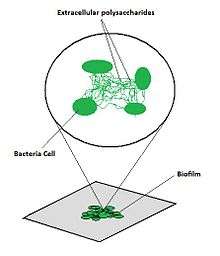

Biofilm formation occurs when free floating microorganisms attach themselves to a surface. They secrete extracellular polymers that provide a structural matrix and facilitate adhesion. Because biofilms protect the bacteria, they are often more resistant to traditional antimicrobial treatments, making them a serious health risk.[1] For example, there are more than one million cases of catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI) reported each year, many of which can be attributed to biofilm-associated bacteria.[2] Currently, there is a large sum of money and research aimed at the use of and protection against biofilms.

Composition of biofilm

Biofilms consist of microorganisms and their self-produced extracellular polymeric substances (EPS). A fully developed biofilm contains many layers including a matrix of EPS with vertical structures, and a conditioning film. Vertical structures of microorganisms sometimes take the form of towers or mushrooms, and are separated by interstitial spaces. Interstitial spaces allow the bulk of the biofilm to easily and rapidly take in nutrients from the surrounding liquid and move byproducts away from the biofilm.[3]

Formation of biofilms are rather complex, but can be generalized in four basic steps: deposition of the conditioning film, microbial (planktonic) attachment to the conditioning film, growth and bacterial colonization and finally biofilm formation.

- Conditioning film: Conditioning films alter the surface properties of the substratum and allow microorganisms to adhere to the surface. For example, when sterile, medical implants are exposed to bodily fluids, proteins, polysaccharides, ions and various other components adhere to the surface and form a conditioning film which "invites" microorganisms that would otherwise be unable to attach to the original surface.[4]

- Adsorption and attachment: While the exact mechanism of microorganism attachment is still unknown, DLVO theory and thermodynamic interaction mechanisms have been used to help explain the initial microbial attachment.

- Growth and colonization: Production of polysaccharides that anchor the bacteria to the surface allow colonies to grow. The growth process is the most significant step in biofilm accumulation when accounting for biofilm mass.[5]

- Biofilm formation: A fully developed biofilm will contain an EPS matrix and vertical structures separated by interstitial spaces. Biofilms have a heterogeneous structure and are capable of mass internal transport.[6]

Biofilm adhesion

How a biofilm adheres to the surface of a material

- Adsorption: the interphase accumulation of cells from the bulk liquid directly on the substratum (surface of the material)

- Once a material is exposed to water, organic molecules begin to adsorb to its surface[7]

- Called the conditioning film: mainly composed of glycoproteins (subject to high turnover rate (not static)

- EPS (extracellular polymeric substances)

- Pre-requisite for biofilm formation

- Binds the bacteria together to form the biofilm

Sticking Efficiency Equation[5]

- = sticking efficiency

- = number of cells adsorbed onto substratum

- = number of cells transported to substratum

- Attachment: the acquisition of cells from the bulk liquid by an existing biofilm

- In order to understand the process of attachment one must first examine the properties of both the substratum and the cell surface

- Substratum: can be either very hydrophobic (Teflon) or hydrophilic (glass)

- Rougher and more hydrophobic materials will develop biofilms faster

- Cell properties: flagella, pili, fimbriae, or glycocalyx may impact rate of microbial attachment[7]

- The reason that these are important is because a cell, once drawn to the substratum must combat the repulsive forces common for all materials; these appendages enable the cell to remain attached until better/more capable attachment mechanisms are set

Inhibiting protein adsorption/ biofilm adhesion

Judging from what has been uncovered through the processes of adsorption and attachment, in order to prevent bacteria from forming a biofilm the substratum should be incredibly smooth. This will make it difficult for the cells to attach to the surface. Another method could be to chemically coat the substratum in order to prevent the conditioning layer and the EPS from forming. The Methods section will cover more detail in this regard.

Methods

Chemical

Antimicrobial coatings

Chemical modifications are the main strategy for biofilm prevention on indwelling medical devices. Antibiotics, biocides, and ion coatings are commonly used chemical methods of biofilm prevention. They prevent biofilm formation by interfering with the attachment and expansion of immature biofilms. Typically, these coatings are effective only for a short time period (about 1 week), after which leaching of the antimicrobial agent reduces the effectiveness of the coating.[8]

The medical uses of silver and silver ions have been known for some time; its use can be traced to the Phoenicians, who would store their water, wine, and vinegar in silver bottles to keep them from spoiling. There has been renewed interest in silver coatings for antimicrobial purposes. The antimicrobial property of silver is known as an oligodynamic effect, a process in which metal ions interfere with the growth and function of bacteria.[9] Several in vitro studies have confirmed the effectiveness of silver at preventing infection, both in coating form and as nanoparticles dispersed in a polymer matrix. However, concerns remain over the use of silver in vivo. Considering the mechanism by which silver interferes with bacterial cell function, some fear that silver may have a similarly toxic effect on human tissue. For this reason, there has been limited use of silver coatings in vivo. Despite this, silver coatings are commonly used on devices such as catheters.[10]

Polymer modification

To avoid the undesirable effects of leaching, antimicrobial agents can be immobilized on device surfaces using long, flexible polymeric chains. These chains are anchored to the device surface by covalent bonds, producing non-leaching, contact-killing surfaces. One in vitro study found that when N-alkylpyridinium bromide, an antimicrobial agent, was attached to a poly(4-vinyl-N-hexylpyridine), the polymer was capable of inactivating ≥ 99% of S. epidermidis, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa bacteria.[11]

Dispersion forces between the polymer chains and the bacterial cells prevent bacteria from binding to the surface and initiating biofilm growth. The concept is similar to that of steric stabilization of colloids. Polymer chains are grafting to a surface via covalent bonding or adsorption. The solubility of these polymers stems from the high conformational entropy of polymer chains in solution. The Χ (Chi) parameter is used to determine whether a polymer will be soluble in a given solution. Χ is given by the equation:

where and are the cohesive energy densities of the polymer and solvent, respectively, is the molar volume of the solution (assuming ), R is the ideal gas constant, and T is temperature in Kelvins. If 0 < < 2, the polymer will be soluble.

Mechanical

Hydrophobicity

The ability of bacteria to adhere to a surface and begin the formation of a biofilm is determined in part by the enthalpy of adhesion of the surface. Adherence is thermodynamically favored if the free enthalpy of adhesion is negative and decreases with increasing free enthalpy values.[11] The free energy of adhesion can be determined by measuring the contact angles of the substances in question. Young's Equation can be used to determine whether if adhesion is favorable or unfavorable:

where , , and are the interfacial energies of the solid–liquid, the liquid–vapor, and the solid–vapor interfaces, respectively. Using this equation, can be determined.

Surface roughness

Surface roughness can also affect biofilm adhesion. Rough, high-energy surfaces are more conducive to biofilm formation and maturation, while smooth surfaces are less susceptible to biofilm adhesion. The roughness of a surface can affect the hydrophobicity or hydrophilicity of the contacting substance, which in turn affects its ability to adhere. The Wenzel equation can be used to estimate the observed contact angle:

where is the apparent contact angle and R is the roughness parameter of the surface. R is the ratio of actual surface area over projected surface area. The Wenzel equation predicts that a hydrophilic surface will have a lower , thus making it easier for bacteria to adhere.[12]

It is thus desirable to maintain a smooth surface on any products that may come in contact with bacteria. Studies have shown that there is a threshold value of surface roughness (Ra = 2 µm) below which biofilm adhesion will reduce no further.[13]

Surface charge

Modification of the surface charge of polymers has also proven to be an effective means of biofilm prevention. Based on the principles of electrostatics charged particles will repel other particles of like charge. The hydrophobicity and the charge of polymeric chains can be controlled by using several backbone compounds and antimicrobial agents. Positively charged polycationic chains enables the molecule to stretch out and generate bactericidal activity.[11]

Techniques

Due to high interest in preventing biofilm formation in the recent years a large number of techniques have been studied to find a good solution. The following section summarizes just a few of the paths being examined in the field but many more techniques outside of these are being developed as well.

Low-energy surface acoustic waves

This technique uses low-energy waves produced from a battery powered device. The device delivers periodic rectangular pulses through an actuator holding a thin piezo plate. The waves spread to the surface, in this case a catheter, creating horizontal waves that prevent the adhesion of planktonic bacteria to surfaces. This technique has been tested on white rabbits and guinea pigs. The results showed a lowered biofilm growth.[14]

Ozonation

Biofilms form as a way of survival for bacteria in aqueous situations. Ozone targets extracellular polysaccharides, a group of bacterial colonies on a surface, and cleaves them. The ozone cuts through the skeleton of the biofilm at a rapid pace thus dissolving it back to harmless microscopic fragments. Ozone is so effective because it is a very strong oxidant and it encounters biofilms in much larger concentrations than most disinfectants like chlorine. This technique has been employed mainly in the spa and pool industry as a way to purify water.[15]

Water purification

When this technique was studied two purification methods were used to treat water. The first was a typical reverse osmosis technique used for pure water. The other was a double reverse osmosis technique with electric deionization which was continuously disinfected with UV light and disinfected weekly with ozone. The tubing it ran through was tested weekly for bacterial colonies. The highly purified water showed a sharp decrease in bacteria colony adherence. Water purification methods are being scrutinized here because it is in this state that contamination is thought to occur and biofilms are formed.[16]

Surface modification

Surface modifications have been a highly studied technique for biofilm prevention. Many methods have been tested and a variety of results have been recorded. These techniques have been the focus of many biomedical studies aiming to reduce harmful biofilm formation on medical devices, especially catheters. The following table is a quick summary of a few surface modification techniques that have been studied.

| Technique | Method of action | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Silver ions | Eluted from sol-gel coating | Silver ions initially impeded biofilm growth. After ten days a biofilm layer was completely established.[17] |

| Polyurethane | Polymer surface modified through glow discharge techniques | Changes in surface roughness showed no effect on biofilm formation. Surfaces with negative surface charge lessened formation.[18] |

| pDMAEMA (poly[2-(dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate]) | Grafted to polyethylene and silicone rubber | Biofilm formations were reduced. Silicone rubber had almost no biofilm present.[19] |

References

- ↑ Donlan, R. M. "Biofilm and Device-Associated Infections." Emerging Infectious Diseases 7.2 (2001)

- ↑ Maki, D. and Tambyah, P. "Engineering Out the Risk for Infection with Urinary Catheters." Emerging Infectious Diseases 7.2 (2001)

- ↑ Secinti, D. K; Özalp, H; Attar, A; Sargon, F. M (2011). "Nanoparticle silver ion coatings inhibit biofilm formation on titanium implants". Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 18 (1): 391–395. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2010.06.022.

- ↑ Habash, M; Reid, G (1999). "Microbial Biofilms: Their Development and Significance for Medical Device—Related Infections". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 39: 887–898. doi:10.1177/00912709922008506.

- 1 2 Hjortsø, Martin A., and Joseph W. Roos. Cell Adhesion: Fundamentals and Biotechnological Applications. New York: M. Dekker, 1995. Print.

- ↑ Lennox, J. "Biofilm Development." Biofilms: The Hypertextbook. Web. 1 May 2011. <http://biofilmbook.hypertextbookshop.com/public_version/contents/chapters/chapter002/section003/blue/page001.html>

- 1 2 Donlan, Rodney M. "Biofilm Formation: A Clinically Relevant Microbiological Process." Clinical Infectious Diseases 33.8 (2001): 1387–392. Print.

- ↑ Dror, N.; Mandel, M.; Hazan, Z.; Lavie, G. Advances in Microbial Biofilm Prevention on Indwelling Medical Devices with Emphasis on Usage of Acoustic Energy. Sensors 2009, 9(4), 2538–2554; doi:10.3390/s90402538. http://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/9/4/2538/

- ↑ Antibacterial effects of Silver, Salt Lake Metals

- ↑ Antibacterial surfaces for biomedical devices. Vasilev K, Cook J, Griesser HJ

- 1 2 3 Prevention of biofilm formation by polymer modification B Jansen and W Kohnen

- ↑ Meiron, T. and Saguy, I. (2007), Adhesion Modeling on Rough Low Linear Density Polyethylene. Journal of Food Science, 72: E485–E491. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00523.x

- ↑ Medical biofilms: detection, prevention, and control, Volume 2 By Jana Jass, Susanne Surman, James T. Walker

- ↑ Hazan, Z., J. Zumeris, H. Jacob, H. Raskin, G. Kratysh, M. Vishnia, N. Dror, T. Barliya, M. Mandel, and G. Lavie. "Effective Prevention of Microbial Biofilm Formation on Medical Devices by Low-Energy Surface Acoustic Waves." Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 50.12 (2006): 4144–152. Print.

- ↑ Barnes, Ronald L., and D. Kevin Caskey. "Using Ozone in the Prevention of Bacterial Biofilm Forming and Scaling." Water Condition & Purification Magazine. 2002. Web. 20 May 2011. <http://www.prozoneint.com/pdf/biofilms.pdf>.

- ↑ Smeets, Ed, Jeroen Kooman, Frank Van Der Sande, Ellen Stobberingh, Peter Frederik, Piet Claessens, Willem Grave, Arend Schot, and Karel Leunissen. "Prevention of Biofilm Formation in Dialysis Water Treatment Systems." Kidney International 63.4 (2003): 1574–576. Print.

- ↑ Stobie, N., B. Duffy, D. Mccormack, J. Colreavy, M. Hidalgo, P. Mchale, and S. Hinder. "Prevention of Staphylococcus Epidermidis Biofilm Formation Using a Low-temperature Processed Silver-doped Phenyltriethoxysilane Sol–gel Coating." Biomaterials 29.8 (2008): 963–69. Print.

- ↑ Jansen, B., and W. Kohnen. "Prevention of Biofilm Formation by Polymer Modification." Journal of Industrial Microbiology 15.4 (1995): 391–96. Print.

- ↑ Contreras-Garcia, A., E. Bucio, G. Brackman, T. Coenye, A. Concheiro, and C. Alvarez-Lorenzo. "Biofilm Inhibition and Drug-eluting Properties of Novel DMAEMA-modified Polyethylene and Silicone Rubber Surfaces." BIOFOULING 27.2 (2011): 123–35. Print.