Chelsea Bun House

The old Chelsea Bun House was a shop in Chelsea which sold buns in the 18th century. It was famous for its Chelsea bun and also did a great trade in hot cross buns at Easter. It was patronised by royalty such as Kings George II, George III and their family.[3]

History

It was on Jew's Row, by Grosvenor Row, on the main road from Pimlico to Chelsea, near Ranelagh Gardens. It seems to have started business early in the 18th century as Jonathan Swift wrote in his journal to Stella on 28 April 1711:[4]

A fine day, but begins to grow a little warm; and that makes your little fat Presto sweat in the forehead. Pray, are not the fine buns sold here in our town; was it not Rrrrrrrrrare Chelsea buns? I bought one to-day in my walk; it cost me a penny; it was stale, and I did not like it, as the man said, &c.

Over a hundred years later, Sir Richard Phillips wrote in A Morning's Walk from London to Kew:[5]

Before me appeared the shops so famed for Chelsea buns, which, for above thirty years, I have never passed without filling my pockets. In the original of these shops, for even of Chelsea buns there are counterfeits, are preserved mementos of domestic events, in the first half of the past century. The bottle-conjuror is exhibited in a toy of his own age; portraits are also displayed of Duke William and other noted personages; a model of a British soldier, in the stiff costume of the same age; and some grotto-works, serve to indicate the taste of a former owner, and were perhaps intended to rival the neighbouring exhibition at Don Saltero's. These buns have afforded a competency, and even wealth; to four generations of the same family; and it is singular, that their delicate flavour, lightness and richness, have never been successfully imitated. The present proprietor told me, with exultation, that George the Second had often been a customer of the shop; that the present King, when Prince George, and often during his reign, had stopped and purchased his buns; and that the Queen, and all the Princes and Princesses, had been among his occasional customers.

The family to which he referred was the Hand family who had succeeded David Loudon as proprietors. Richard Hand was known as "Captain Bun". His wife, Mrs. Hand, ran the business after his death. Queen Caroline, who had brought her children there, presented Mrs. Hand with a silver mug containing five guineas. Upon her death, her son ran the business and he also supplied butter to local customers. When he died too, his older brother took over. He was a retired soldier — a poor knight of Windsor — and, like his brother, was eccentric. There were no more Hands so, on his death in 1839, the property reverted to the Crown and the contents were auctioned off.[6]

Easter

On Good Friday, it was a tradition for the working classes, such as servants and apprentices, to buy a hot cross bun. The Greenwich Fair was the most well-known Easter fair in London, but great crowds would also assemble on the Five Fields — an open space which was subsequently developed as Eaton and Belgrave Squares to form Belgravia. The bun house would open for business as early as three or four in the morning and the crowds would press on it so fiercely that buns would only be sold through openings in the shutters. Constables were required to keep good order and, in 1792, the crowd was so great that Mrs Hand made a public announcement that there would be no sales of hot cross buns in the following year,[7]

Royal Bun House, Chelsea, Good Friday

No Cross Buns.

Mrs. Hand respectfully informs her friends and the public, that in consequence of the great concourse of people which assembled before her house at a very early hour, on the morning of Good Friday last, by which her neighbours (with whom she has always lived in friendship and repute) have been much alarmed and annoyed; it having also been intimated, that to encourage or countenance a tumultuous assembly at this particular period might be attended with consequences more serious than have hitherto been apprehended; desirous, therefore, of testifying her regard and obedience to those laws by which she is happily protected, she is determined, though much to her loss, not to sell Cross Buns on that day to any person whatever, but Chelsea buns as usual.

This restraint did not last and so, on its final Good Friday of 1839, the bun house still sold a great number of buns – over 24,000 according to The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction.[nb 1]

Literary references

Anne Manning wrote a fictional account of the place in The Old Chelsea Bun-House: a Tale of the Last Century, which was published in 1855.[10]

In short, our Milk and Whey became in such repute that we got on from two Cows to six, and at length to Twelve, and had the largest Milk-walk in the neighbourhood. Our man, Andrew, who was from Devonshire, looked after the Dairy; and Saunders, who was a Scot, was our baker; but a Mistress's Eye is worth two Pair of Hands; and one Reason of our Success was undoubtedly that we looked after our Business ourselves, no matter how much Money was coming into the Till.

Notes

- ↑ The contemporary report in The Mirror states "it appears that he sold on last Good Friday, April 18th, 1839, upwards of 24,000 buns..."[8] Later sources such as George Bryan's Chelsea, in the Olden & Present Times give the number as 240,000[9] but this does not seem consistent with the revenue of about £100 and so may be a misprint.

References

- ↑ Exterior of the Old Chelsea Bun House: 1839, Museum of London

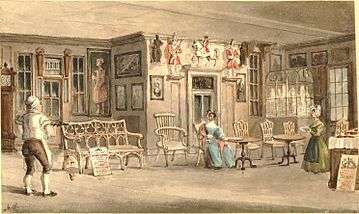

- ↑ Drawing - View of the interior of the Chelsea Bun House (1880,1113.2421), British Museum

- ↑ "Chelsea Bun House", London Encyclopaedia, Pan Macmillan, 2010, p. 155, ISBN 9781405049252

- ↑ "Chelsea Bun-House", The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction, Vol. 33: 210–211

- ↑ Sir Richard Phillips (1817). A morning's walk from London to Kew. p. 26.

- ↑ "Chelsea Bunhouse", The Gentleman's Magazine, Vol. 11: 466–467

- ↑ Edward Walford (1878), Old and New London, Vol. 5 Chelsea, pp. 50–70

- ↑ "Demolition of the Chelsea Bun-House", The Mirror of Literature, Amusement,and Instruction, XXXIII (947), p. 287, 4 May 1839

- ↑ George Bryan (1869), "The Original Chelsea Bunhouse", Chelsea, in the Olden & Present Times, London, pp. 200–202,

so lately as 1839 no less than 240,000 were sold here on Good Friday. This may appear to many to be an incredulous number; but few persons at the present time can form an adequate idea of the immense demand for them.

- ↑ Anne Manning (1855), The old Chelsea bun-house, p. 29