Turtle

| Turtles Temporal range: Late Jurassic – Present,[1] 157–0 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Testudinata |

| Order: | Testudines Batsch, 1788 [2] |

| Subgroups[1] | |

|

Cryptodira | |

| Diversity | |

| 14 extant families with ca. 300 species | |

| |

| blue: sea turtles, black: land turtles | |

Turtles are reptiles of the order Testudines (or Chelonii[3]) characterised by a special bony or cartilaginous shell developed from their ribs and acting as a shield.[4] "Turtle" may refer to the order as a whole (American English) or to fresh-water and sea-dwelling testudines (British English).[5]

The order Testudines includes both extant (living) and extinct species. The earliest known members of this group date from 157 million years ago,[1] making turtles one of the oldest reptile groups and a more ancient group than snakes or crocodilians. Of the 327 known species alive today, some are highly endangered.[6][7]

Turtles are ectotherms—animals commonly called cold-blooded—meaning that their internal temperature varies according to the ambient environment. However, because of their high metabolic rate, leatherback sea turtles have a body temperature that is noticeably higher than that of the surrounding water.

Turtles are classified as amniotes, along with other reptiles, birds, and mammals. Like other amniotes, turtles breathe air and do not lay eggs underwater, although many species live in or around water.

Turtle, tortoise, or terrapin

The word chelonian is popular among veterinarians, scientists, and conservationists working with these animals as a catch-all name for any member of the superorder Chelonia, which includes all turtles living and extinct, as well as their immediate ancestors. Chelonia is based on the Greek word χελώνη chelone "tortoise", "turtle" (another relevant word is χέλυς chelys "tortoise"),[8][9] also denoting armor or interlocking shields;[10] testudines, on the other hand, is based on the Latin word testudo "tortoise".[11] "Turtle" may either refer to the order as a whole, or to particular turtles that make up a form taxon that is not monophyletic.

The meaning of the word turtle differs from region to region. In North America, all chelonians are commonly called turtles, including terrapins and tortoises.[12][13] In Great Britain, the word turtle is used for sea-dwelling species, but not for tortoises.

The term tortoise usually refers to any land-dwelling, non-swimming chelonian.[13] Most land-dwelling chelonians are in the Testudinidae family, only one of the fourteen extant turtle families.[14]

Terrapin is used to describe several species of small, edible, hard-shell turtles, typically those found in brackish waters, and is an Algonquian word for turtle.[12][15]

Some languages do not have this distinction, as all of these are referred to by the same name. For example, in Spanish, the word tortuga is used for turtles, tortoises, and terrapins. A sea-dwelling turtle is tortuga marina, a freshwater species tortuga de río, and a tortoise tortuga terrestre.[16]

Anatomy and morphology

The largest living chelonian is the leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea), which reaches a shell length of 200 cm (6.6 ft) and can reach a weight of over 900 kg (2,000 lb). Freshwater turtles are generally smaller, but with the largest species, the Asian softshell turtle Pelochelys cantorii, a few individuals have been reported up to 200 cm (6.6 ft). This dwarfs even the better-known alligator snapping turtle, the largest chelonian in North America, which attains a shell length of up to 80 cm (2.6 ft) and weighs as much as 113.4 kg (250 lb).[17] Giant tortoises of the genera Geochelone, Meiolania, and others were relatively widely distributed around the world into prehistoric times, and are known to have existed in North and South America, Australia, and Africa. They became extinct at the same time as the appearance of man, and it is assumed humans hunted them for food. The only surviving giant tortoises are on the Seychelles and Galápagos Islands and can grow to over 130 cm (51 in) in length, and weigh about 300 kg (660 lb).[18]

The largest ever chelonian was Archelon ischyros, a Late Cretaceous sea turtle known to have been up to 4.6 m (15 ft) long.[19]

The smallest turtle is the speckled padloper tortoise of South Africa. It measures no more than 8 cm (3.1 in) in length and weighs about 140 g (4.9 oz). Two other species of small turtles are the American mud turtles and musk turtles that live in an area that ranges from Canada to South America. The shell length of many species in this group is less than 13 cm (5.1 in) in length.

Neck retraction

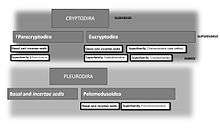

Turtles are divided into two groups, according to how they retract their necks into their shells (something the ancestral Proganochelys could not do). The Cryptodira retract their necks backwards while contracting it under their spine, whereas the Pleurodira contract their necks to the side.

Head

Most turtles that spend most of their lives on land have their eyes looking down at objects in front of them. Some aquatic turtles, such as snapping turtles and soft-shelled turtles, have eyes closer to the top of the head. These species of turtle can hide from predators in shallow water, where they lie entirely submerged except for their eyes and nostrils. Near their eyes, sea turtles possess glands that produce salty tears that rid their body of excess salt taken in from the water they drink.

Turtles have rigid beaks and use their jaws to cut and chew food. Instead of having teeth, which they appear to have lost about 150-200 million years ago,[20] the upper and lower jaws of the turtle are covered by horny ridges. Carnivorous turtles usually have knife-sharp ridges for slicing through their prey. Herbivorous turtles have serrated-edged ridges that help them cut through tough plants. They use their tongues to swallow food, but unlike most reptiles, they cannot stick out their tongues to catch food.

Shell

The upper shell of the turtle is called the carapace. The lower shell that encases the belly is called the plastron. The carapace and plastron are joined together on the turtle's sides by bony structures called bridges. The inner layer of a turtle's shell is made up of about 60 bones that include portions of the backbone and the ribs, meaning the turtle cannot crawl out of its shell. In most turtles, the outer layer of the shell is covered by horny scales called scutes that are part of its outer skin, or epidermis. Scutes are made up of the fibrous protein keratin that also makes up the scales of other reptiles. These scutes overlap the seams between the shell bones and add strength to the shell. Some turtles do not have horny scutes; for example, the leatherback sea turtle and the soft-shelled turtles have shells covered with leathery skin instead.

The rigid shell means that turtles cannot breathe as other reptiles do, by changing the volume of their chest cavities via expansion and contraction of the ribs. Instead, they breathe in two ways. First, they employ limb pumping, sucking air into their lungs and pushing it out by moving the limbs in and out relative to the shell. Secondly, when the abdominal muscles that cover the posterior opening of the shell contract, the pressure inside the shell and lungs decreases, drawing air into the lungs, allowing these muscles to function in much the same way as the mammalian diaphragm. A second set of abdominal muscles face the opposite way and when they contract they expel air under positive pressure.[21]

The shape of the shell gives helpful clues about how a turtle lives. Most tortoises have a large, dome-shaped shell that makes it difficult for predators to crush the shell between their jaws. One of the few exceptions is the African pancake tortoise, which has a flat, flexible shell that allows it to hide in rock crevices. Most aquatic turtles have flat, streamlined shells, which aid in swimming and diving. American snapping turtles and musk turtles have small, cross-shaped plastrons that give them more efficient leg movement for walking along the bottom of ponds and streams.

The color of a turtle's shell may vary. Shells are commonly colored brown, black, or olive green. In some species, shells may have red, orange, yellow, or grey markings, often spots, lines, or irregular blotches. One of the most colorful turtles is the eastern painted turtle, which includes a yellow plastron and a black or olive shell with red markings around the rim.

Tortoises, being land-based, have rather heavy shells. In contrast, aquatic and soft-shelled turtles have lighter shells that help them avoid sinking in water and swim faster with more agility. These lighter shells have large spaces called fontanelles between the shell bones. The shells of leatherback sea turtles are extremely light because they lack scutes and contain many fontanelles.

It has been suggested by Jackson (2002) that the turtle shell can function as pH buffer. To endure through anoxic conditions, such as winter periods trapped beneath ice or within anoxic mud at the bottom of ponds, turtles utilize two general physiological mechanisms. In the case of prolonged periods of anoxia, it has been shown that the turtle shell both releases carbonate buffers and uptakes lactic acid.[22]

Skin and molting

As mentioned above, the outer layer of the shell is part of the skin; each scute (or plate) on the shell corresponds to a single modified scale. The remainder of the skin has much smaller scales, similar to the skin of other reptiles. Turtles do not molt their skins all at once as snakes do, but continuously in small pieces. When turtles are kept in aquaria, small sheets of dead skin can be seen in the water (often appearing to be a thin piece of plastic) having been sloughed off when the animals deliberately rub themselves against a piece of wood or stone. Tortoises also shed skin, but dead skin is allowed to accumulate into thick knobs and plates that provide protection to parts of the body outside the shell.

By counting the rings formed by the stack of smaller, older scutes on top of the larger, newer ones, it is possible to estimate the age of a turtle, if one knows how many scutes are produced in a year.[23] This method is not very accurate, partly because growth rate is not constant, but also because some of the scutes eventually fall away from the shell.

Limbs

Terrestrial tortoises have short, sturdy feet. Tortoises are famous for moving slowly, in part because of their heavy, cumbersome shells, which restrict stride length.

Amphibious turtles normally have limbs similar to those of tortoises, except that the feet are webbed and often have long claws. These turtles swim using all four feet in a way similar to the dog paddle, with the feet on the left and right side of the body alternately providing thrust. Large turtles tend to swim less than smaller ones, and the very big species, such as alligator snapping turtles, hardly swim at all, preferring to walk along the bottom of the river or lake. As well as webbed feet, turtles have very long claws, used to help them clamber onto riverbanks and floating logs upon which they bask. Male turtles tend to have particularly long claws, and these appear to be used to stimulate the female while mating. While most turtles have webbed feet, some, such as the pig-nosed turtle, have true flippers, with the digits being fused into paddles and the claws being relatively small. These species swim in the same way as sea turtles do (see below).

Sea turtles are almost entirely aquatic and have flippers instead of feet. Sea turtles fly through the water, using the up-and-down motion of the front flippers to generate thrust; the back feet are not used for propulsion but may be used as rudders for steering. Compared with freshwater turtles, sea turtles have very limited mobility on land, and apart from the dash from the nest to the sea as hatchlings, male sea turtles normally never leave the sea. Females must come back onto land to lay eggs. They move very slowly and laboriously, dragging themselves forwards with their flippers.

Behavior

Senses

Turtles are thought to have exceptional night vision due to the unusually large number of rod cells in their retinas. Turtles have color vision with a wealth of cone subtypes with sensitivities ranging from the near ultraviolet (UVA) to red. Some land turtles have very poor pursuit movement abilities, which are normally found only in predators that hunt quick-moving prey, but carnivorous turtles are able to move their heads quickly to snap.

Intelligence

It has been reported that wood turtles are better than white rats at learning to navigate mazes.[24] Case studies exist of turtles playing.[24] They do, however, have a very low encephalization quotient (relative brain to body mass), and their hard shells enable them to live without fast reflexes or elaborate predator avoidance strategies.[25] In the laboratory, turtles (Pseudemys nelsoni) can learn novel operant tasks and have demonstrated a long-term memory of at least 7.5 months.[26]

Ecology and life history

Although many turtles spend large amounts of their lives underwater, all turtles and tortoises breathe air and must surface at regular intervals to refill their lungs. They can also spend much or all of their lives on dry land. Aquatic respiration in Australian freshwater turtles is currently being studied. Some species have large cloacal cavities that are lined with many finger-like projections. These projections, called papillae, have a rich blood supply and increase the surface area of the cloaca. The turtles can take up dissolved oxygen from the water using these papillae, in much the same way that fish use gills to respire.[27]

Like other reptiles, turtles lay eggs that are slightly soft and leathery. The eggs of the largest species are spherical while the eggs of the rest are elongated. Their albumen is white and contains a different protein from bird eggs, such that it will not coagulate when cooked. Turtle eggs prepared to eat consist mainly of yolk. In some species, temperature determines whether an egg develops into a male or a female: a higher temperature causes a female, a lower temperature causes a male. Large numbers of eggs are deposited in holes dug into mud or sand. They are then covered and left to incubate by themselves. Depending on the species, the eggs will typically take 70–120 days to hatch. When the turtles hatch, they squirm their way to the surface and head toward the water. There are no known species in which the mother cares for her young.

Sea turtles lay their eggs on dry, sandy beaches. Immature sea turtles are not cared for by the adults. Turtles can take many years to reach breeding age, and in many cases, breed every few years rather than annually.

Researchers have recently discovered a turtle's organs do not gradually break down or become less efficient over time, unlike most other animals. It was found that the liver, lungs, and kidneys of a centenarian turtle are virtually indistinguishable from those of its immature counterpart. This has inspired genetic researchers to begin examining the turtle genome for longevity genes.[28]

A group of turtles is known as a bale.[29]

Diet

A turtle's diet varies greatly depending on the environment in which it lives. Adult turtles typically eat aquatic plants; invertebrates such as insects, snails, and worms; and have been reported to occasionally eat dead marine animals. Several small freshwater species are carnivorous, eating small fish and a wide range of aquatic life. However, protein is essential to turtle growth and juvenile turtles are purely carnivorous.

Sea turtles typically feed on jellyfish, sponge, and other soft-bodied organisms. Some species of sea turtle with stronger jaws have been observed to eat shellfish while some species, such as the green sea turtle, do not eat any meat at all and, instead, have a diet largely made up of algae.[30]

Systematics and evolution

Based on body fossils, the first proto-turtles are believed to have existed in the late Triassic Period of the Mesozoic era, about 220 million years ago, and their shell, which has remained a remarkably stable body plan, is thought to have evolved from bony extensions of their backbones and broad ribs that expanded and grew together to form a complete shell that offered protection at every stage of its evolution, even when the bony component of the shell was not complete. This is supported by fossils of the freshwater Odontochelys semitestacea or "half-shelled turtle with teeth", from the late Triassic, which have been found near Guangling in southwest China. Odontochelys displays a complete bony plastron and an incomplete carapace, similar to an early stage of turtle embryonic development.[31] Prior to this discovery, the earliest-known fossil turtle ancestors, like Proganochelys, were terrestrial and had a complete shell, offering no clue to the evolution of this remarkable anatomical feature. By the late Jurassic, turtles had radiated widely, and their fossil history becomes easier to read.

Their exact ancestry has been disputed. It was believed they are the only surviving branch of the ancient evolutionary grade Anapsida, which includes groups such as procolophonids, millerettids, protorothyrids, and pareiasaurs. All anapsid skulls lack a temporal opening while all other extant amniotes have temporal openings (although in mammals, the hole has become the zygomatic arch). The millerettids, protorothyrids, and pareiasaurs became extinct in the late Permian period and the procolophonoids during the Triassic.[32]

However, it was later suggested that the anapsid-like turtle skull may be due to reversion rather than to anapsid descent. More recent morphological phylogenetic studies with this in mind placed turtles firmly within diapsids, slightly closer to Squamata than to Archosauria.[33][34] All molecular studies have strongly upheld the placement of turtles within diapsids; some place turtles within Archosauria,[35] or, more commonly, as a sister group to extant archosaurs,[36][37][38][39] though an analysis conducted by Lyson et al. (2012) recovered turtles as the sister group of lepidosaurs instead.[40] Reanalysis of prior phylogenies suggests that they classified turtles as anapsids both because they assumed this classification (most of them studying what sort of anapsid turtles are) and because they did not sample fossil and extant taxa broadly enough for constructing the cladogram. Testudines were suggested to have diverged from other diapsids between 200 and 279 million years ago, though the debate is far from settled.[33][36][41] Even the traditional placement of turtles outside Diapsida cannot be ruled out at this point. A combined analysis of morphological and molecular data conducted by Lee (2001) found turtles to be anapsids (though a relationship with archosaurs couldn't be statistically rejected).[42] Similarly, a morphological study conducted by Lyson et al. (2010) recovered them as anapsids most closely related to Eunotosaurus.[43] A molecular analysis of 248 nuclear genes from 16 vertebrate taxa suggests that turtles are a sister group to birds and crocodiles (the Archosauria).[44] The date of separation of turtles and birds and crocodiles was estimated to be 255 million years ago. The most recent common ancestor of living turtles, corresponding to the split between Pleurodira and Cryptodira, was estimated to have occurred around 157 million years ago.[1][45] The oldest definitive crown-group turtle (member of the modern clade Testudines) is the species Caribemys oxfordiensis from the late Jurassic period (Oxfordian stage).[1] Through utilizing the first genomic-scale phylogenetic analysis of ultraconserved elements (UCEs) to investigate the placement of turtles within reptiles, Crawford et al. (2012) also suggest that turtles are a sister group to birds and crocodiles (the Archosauria).[46]

The first genome-wide phylogenetic analysis was completed by Wang et al. (2013). Using the draft genomes of Chelonia mydas and Pelodiscus sinensis, the team used the largest turtle data set to date in their analysis and concluded that turtles are likely a sister group of crocodilians and birds (Archosauria).[47] This placement within the diapsids suggests that the turtle lineage lost diapsid skull characteristics as it now possesses an anapsid-like skull.

The earliest known fully shelled member of the turtle lineage is the late Triassic Proganochelys. This genus already possessed many advanced turtle traits, and thus probably indicates many millions of years of preceding turtle evolution; this is further supported by evidence from fossil tracks from the Early Triassic of the United States (Wyoming and Utah) and from the Middle Triassic of Germany, indicating that proto-turtles already existed as early as Early Triassic.[48] Proganochelys lacked the ability to pull its head into its shell, had a long neck, and had a long, spiked tail ending in a club. While this body form is similar to that of ankylosaurs, it resulted from convergent evolution.

Turtles are divided into two extant suborders: the Cryptodira and the Pleurodira. The Cryptodira is the larger of the two groups and includes all the marine turtles, the terrestrial tortoises, and many of the freshwater turtles. The Pleurodira are sometimes known as the side-necked turtles, a reference to the way they retract their heads into their shells. This smaller group consists primarily of various freshwater turtles.

Phylogeny of living turtles

The following phylogeny of living turtles is based on the work of Crawford et al. (2015)[49] and Guillon et al. (2012).[50]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Classification of turtles

Order Testudinata Klein 1760[51]

- Genus †Pappochelys Schoch & Sues 2015

- Family †Proganochelyidae Baur 1887

- Family †Australochelidae Gaffney & Kitching 1994 sensu Lee 1997

- Family †Proterochersidae Nopcsa 1928

- Clade †Mesochelydia

- Family †Indochelyidae Datta, Manna, Ghosh & Das 2000

- Family †Heckerochelyidae Sukhanov 2006

- Clade †Perichelydia

- Family †Chelycarapookidae Warren 1969

- Family †Sichuanchelyidae Tong et al. 2012

- Family †Solemydidae de Lapparent de Broin & Murelaga 1996

- Clade †Meiolaniformes

- Family †Meiolaniidae Lydekker 1887

- Family †Otwayemyidae Gaffney et al. 1998

- Genus †Trapalcochelys Sterli, de la Fuente & Cerda 2013

- Genus †Chubutemys Gaffney et al. 2007

- Genus †Peligrochelys Sterli & de la Fuente 2012

- Clade †Meiolaniformes

- Family †Kallokibotiidae Nopcsa 1923

- Clade Testudines Linnaeus, 1758

- Suborder Pleurodira Cope 1864

- Family †Apertotemporalidae Kühne 1937

- Family †Platychelyidae Brän 1965 sensu Gaffney, Tong & Buffetaut 2006

- Family †Dortokidae Lapparent de Broin & Murelaga 1996

- Family †Notoemyidae Fernandez & Fuente 1994

- Superfamily †Cheloides Gray 1825 sensu Gaffney, Tong & Buffetaut 2006

- Family Chelidae Gray 1825

- Superfamily †Pelomedusoides Cope 1868 sensu Broin 1988

- Family †Araripemydidae Price 1973

- Family Pelomedusidae (African sideneck turtles)

- Family †Euraxemydidae Gaffney, Tong & Buffetaut 2006

- Family †Bothremydidae Baur 1891

- Family Podocnemididae Cope 1868 (Madagascan big-headed and American sideneck river turtles)

- Suborder Cryptodira Duméril & Bibron 1835

- Infraorder Paracryptodira

- Family †Pleurosternidae Cope 1868

- Family †Compsemyidae

- Family †Baenidae Cope 1882

- Infraorder Eucryptodira Gaffney 1975a sensu Gaffney 1984

- Family †Macrobaenidae Sukhanov 1964

- Family †Eurysternidae Dollo 1886

- Family †Plesiochelyidae Baur 1888

- Family †Xinjiangchelyidae Nesov 1990

- Clade Centrocryptodira

- Family †Osteopygidae Zangerl 1953

- Family †Sinemydidae Yeh 1963

- Clade Polycryptodira Gaffney 1988

- Clade Pantrionychia

- Family †Adocidae

- Superfamily Trionychoidea Gray 1870

- Family Carettochelyidae (pignose turtles)

- Family Trionychidae (softshell turtles)

- Superfamily Testudinoidea Baur 1893

- Family †Haichemydidae Sukhanov & Narmandakh 2006

- Family †Lindholmemydidae Chkhikvadze 1970

- Family †Sinochelyidae Chkhikvadze 1970

- Family Emydidae (pond, box, and water turtles)

- Family Geoemydidae (Asian river turtles, Asian leaf turtles, Asian box turtles, and roofed turtles)

- Family Testudinidae (true tortoises)

- Family Geoemydidae

- Clade Americhelydia

- Family Chelydridae (snapping turtles)

- Superfamily Kinosternoidea

- Family Dermatemydidae (river turtles)

- Family Kinosternidae (mud turtles)

- Superfamily Chelonioidea (sea turtles)

Sea turtle at Henry Doorly Zoo, Omaha NE

Sea turtle at Henry Doorly Zoo, Omaha NE- Family †Toxochelyidae Baur 1895

- Family Cheloniidae (green sea turtles and relatives)

- Family †Thalassemydidae

- Family Dermochelyidae (leatherback sea turtles)

- Family †Protostegidae Cope, 1872

- Clade Pantrionychia

- Infraorder Paracryptodira

- Suborder Pleurodira Cope 1864

Fossil record

Turtle fossils of hatchling and nestling size have been documented in the scientific literature.[52] Paleontologists from North Carolina State University have found the fossilized remains of the world's largest turtle in a coal mine in Colombia. The specimen named as Carbonemys cofrinii is around 60 million years old and nearly 2.4 m (8 ft) long.[53]

On a few rare occasions, paleontologists have succeeded in unearthing large numbers of Jurassic or Cretaceous turtle skeletons accumulated in a single area (the Nemegt Formation in Mongolia, the Turtle Graveyard in North Dakota, or the Black Mountain Turtle Layer in Wyoming). The most spectacular find of this kind to date occurred in 2009 in Shanshan County in Xinjiang, where over a thousand ancient freshwater turtles apparently died after the last water hole in an area dried out during a major drought.[54][55]

Though absent from New Zealand in recent times, turtle fossils are known from the Miocene Saint Bathans Fauna, represented by a meiolaniid and pleurodires.[56]

Genomics

Turtles possess diverse chromosome numbers (2n = 28–66) and a myriad of chromosomal rearrangements have occurred during evolution.[57]

In captivity

Turtles, particularly small terrestrial and freshwater turtles, are commonly kept as pets. Among the most popular are Russian tortoises, spur-thighed tortoises, and red-eared sliders.[58]

In the United States, due to the ease of contracting salmonellosis through casual contact with turtles, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) established a regulation in 1975 to discontinue the sale of turtles under 4 in (100 mm).[59] It is illegal in every state in the U.S. for anyone to sell any turtles under 4 inches (10 cm) long. Many stores and flea markets still sell small turtles due to a loophole in the FDA regulation which allows turtles under 4 in (100 mm) to be sold for educational purposes.[60][61]

Some states have other laws and regulations regarding possession of red-eared sliders as pets because they are looked upon as invasive species or pests where they are not native, but have been introduced through the pet trade. As of July 1, 2007, it is illegal in Florida to sell any wild type red-eared slider.[62] Unusual color varieties such as albino and pastel red-eared sliders, which are derived from captive breeding, are still allowed for sale.

As food, traditional medicine, and cosmetics

Right: Turtle plastrons among other plants and animals parts are used in traditional Chinese medicines. (Other items in the image are dried lingzhi, snake, luo han guo, and ginseng)

The flesh of turtles, calipash or calipee, was and still is considered a delicacy in a number of cultures.[6] Turtle soup has been a prized dish in Anglo-American cuisine,[63] and still remains so in some parts of Asia. Gopher tortoise stew was popular with some groups in Florida.[64]

Turtles remain a part of the traditional diet on the island of Grand Cayman, so much so that when wild stocks became depleted, a turtle farm was established specifically to raise sea turtles for their meat. The farm also releases specimens to the wild as part of an effort to repopulate the Caribbean Sea.[65]

Fat from turtles is also used in the Caribbean and in Mexico as a main ingredient in cosmetics, marketed under its Spanish name crema de tortuga.[66]

Turtle plastrons (the part of the shell that covers a tortoise from the bottom) are widely used in traditional Chinese medicine; according to statistics, Taiwan imports hundreds of tons of plastrons every year.[67] A popular medicinal preparation based on powdered turtle plastron (and a variety of herbs) is the guilinggao jelly;[68] these days, though, it is typically made with only herbal ingredients.

Conservation status

In February 2011, the Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group published a report about the top 25 species of turtles most likely to become extinct, with a further 40 species at very high risk of becoming extinct. This list excludes sea turtles, however, both the leatherback and the Kemp's ridley would make the top 25 list. The report is due to be updated in four years time allowing to follow the evolution of the list. Between 48 and 54% of all 328 of their species considered threatened, turtles and tortoises are at a much higher risk of extinction than many other vertebrates. Of the 263 species of freshwater and terrestrial turtles, 117 species are considered Threatened, 73 are either Endangered or Critically Endangered and 1 is Extinct. Of the 58 species belonging to the Testudinidae family, 33 species are Threatened, 18 are either Endangered or Critically Endangered, 1 is Extinct in the wild and 7 species are Extinct. 71% of all tortoise species are either gone or almost gone. Asian species are the most endangered, closely followed by the five endemic species from Madagascar. Turtles face many threats, including habitat destruction, harvesting for consumption, and the pet trade. The high extinction risk for Asian species is primarily due to the long-term unsustainable exploitation of turtles and tortoises for consumption and traditional Chinese medicine, and to a lesser extent for the international pet trade.[69]

Efforts have been made by Chinese entrepreneurs to satisfy increasing demand for turtle meat as gourmet food and traditional medicine with farmed turtles, instead of wild-caught ones; according to a study published in 2007, over a thousand turtle farms operated in China.[70][71] Turtle farms in Oklahoma and Louisiana raise turtles for export to China as well.[71]

Nonetheless, wild turtles continue to be caught and sent to market in large number (as well as to turtle farms, to be used as breeding stock[70]), resulting in a situation described by conservationists as "the Asian turtle crisis".[72] In the words of the biologist George Amato, "the amount and the volume of captured turtles... vacuumed up entire species from areas in Southeast Asia", even as biologists still did not know how many distinct turtle species live in the region.[73] About 75% of Asia's 90 tortoise and freshwater turtle species are estimated to have become threatened.[71]

Harvesting wild turtles is legal in a number of states in the USA.[71] In one of these states, Florida, just a single seafood company in Fort Lauderdale was reported in 2008 as buying about 5,000 pounds of softshell turtles a week. The harvesters (hunters) are paid about $2 a pound; some manage to catch as many as 30–40 turtles (500 pounds) on a good day. Some of the catch gets to the local restaurants, while most of it is exported to Asia. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission estimated in 2008 that around 3,000 pounds of softshell turtles were exported each week via Tampa International Airport.[74]

Nonetheless, the great majority of turtles exported from the USA are farm raised. According to one estimate by the World Chelonian Trust, about 97% of 31.8 million animals harvested in the U.S. over a three-year period (November 4, 2002 – November 26, 2005) were exported.[71][75] It has been estimated (presumably, over the same 2002–2005 period) that about 47% of the US turtle exports go to People's Republic of China (predominantly to Hong Kong), another 20% to Taiwan, and 11% to Mexico.[76][77]

TurtleSAt is a smartphone app that has been developed in Australia in honor of World Turtle Day to help in the conservation of fresh water turtles in Australia. The app will allow the user to identify turtles with a picture guide and the location of turtles using the phones GPS to record sightings and help find hidden turtle nesting grounds. The app has been developed because there has been a high per cent of decline of fresh water turtles in Australia due to foxes, droughts, and urban development. The aim of the app is to reduce the number of foxes and help with targeting feral animal control.[78]

Testudinology research organizations

Testudinology, also known as cheloniology, is the zoological study of animals belonging to the order Testudines or Chelonii. A person who specializes in this field is called a testudinologist. Notable testudinology research organizations include:

- Archie Carr Center for Sea Turtle Research, University of Florida

- Chelonian Research Institute, founded by Peter Pritchard, in Oviedo, Florida

- Dewees Island Turtle Team

- East Coast Biologists, Inc.

- Ecological Associates, Inc.

- Hawaii Preparatory Academy Sea Turtle Research Program

- Innovation Academy for Engineering, Environmental & Marine Science

- Inwater Research Group

- Oceana

- Padre Island National Seashore, Division of Sea Turtle Science and Recovery

- Marine Turtle Research Group of China, a.k.a. the National Huidong Sea Turtle Reserve (Chinese: 广东惠东海龟国家级自然保护区管理局)

- Israel Nature and Parks Authority - Sea Turtle Rescue Center (Hebrew: המרכז הארצי להצלת צבי ים)

- Red Sea Turtle Project

- Chelonian Research Group (not to be confused with the Chelonian Research Institute of the U.S.)

- Marine Turtle Research Group

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 Joyce 2007

- ↑ "Testudines". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- ↑ Dubois & Bour 2010

- ↑ Hutchinson 1996

- ↑ "Oxford English Dictionary: Turtle".

- 1 2 Barzyk 1999

- ↑ Herpetology: An Introductory Biology of Amphibians and Reptiles

- ↑ χελώνη, χέλυς. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ↑ Stone 2006, p. 85

- ↑ Brennessel 2006, p. 10

- ↑ testudo. Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short. A Latin Dictionary on Perseus Project.

- 1 2 Ernst & Lovich 2009, p. 3

- 1 2 Fergus 2007

- ↑ Iverson, Kimerling & Kiester 1999

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "terrapin". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ , Diccionario de la Real Academia Española

- ↑ National Geographic 2011.

- ↑ Connor 2009

- ↑ Everhart 2012

- ↑ Long in the tooth: Genome proves turtles evolve…very slowly

- ↑ Druzisky, K. A. and Brainerd, E. L. (1 October 2001). "Buccal oscillation and lung ventilation in a semi-aquatic turtle, Platysternon megacephalum" (PDF). Zoology. 104. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ↑ Jackson 2002

- ↑ Pet Education 2012.

- 1 2 Angier, Natalie (December 16, 2006). "Ask Science". The New York Times. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- ↑ Jerison, H.F. (1983). Eisenberg, J.F. & Kleiman, D.G., eds. Advances in the Study of Mammalian Behavior. Pittsburgh: Special Publication of the American Society of Mammalogists, nr. 7. pp. 113–146.

- ↑ Davis, K.M. and Burghardt, G.M. (2007). "Training and long-term memory of a novel food acquisition task in a turtle (Pseudemys nelsoni)". Behavioural Processes. 75 (2): 225–230. doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2007.02.021.

- ↑ Priest & Franklin 2002

- ↑ Angier 2012

- ↑ "What do you call a group of ...? | Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries | English. Retrieved 2017-01-29.

- ↑ "What Do Turtles Eat?". what-do-turtles-eat.com. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ↑ Li et al. 2008

- ↑ Laurin 1996

- 1 2 Rieppel & DeBraga 1996

- ↑ Müller 2004

- ↑ Mannen & Li 1999

- 1 2 Zardoya & Meyer 1998

- ↑ Iwabe et al. 2004

- ↑ Roos, Aggarwal & Janke 2007

- ↑ Katsu et al. 2010

- ↑ Lyson et al. 2012

- ↑ Benton 2000

- ↑ Lee 2001

- ↑ Lyson et al. 2010

- ↑ Chiari et al. 2012

- ↑ Anquetin 2012

- ↑ Crawford et al. 2012

- ↑ Wang, Zhuo; Pascual-Anaya, J; Zadissa, A; Li, W; Niimura, Y; Huang, Z; Li, C; White, S; Xiong, Z; Fang, D; Wang, B; Ming, Y; Chen, Y; Zheng, Y; Kuraku, S; Pignatelli, M; Herrero, J; Beal, K; Nozawa, M; Li, Q; Wang, J; Zhang, H; Yu, L; Shigenobu, S; Wang, J; Liu, J; Flicek, P; Searle, S; Wang, J; et al. (27 March 2013). "The draft genomes of soft-shell turtle and green sea turtle yield insights into the development and evolution of the turtle-specific body plan". Nature Genetics. 45 (701–706): 701–6. PMC 4000948

. PMID 23624526. doi:10.1038/ng.2615. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

. PMID 23624526. doi:10.1038/ng.2615. Retrieved 15 November 2013. - ↑ Asher J. Lichtig; Spencer G. Lucas; Hendrik Klein; David M. Lovelace (2017). "Triassic turtle tracks and the origin of turtles". Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology. in press. doi:10.1080/08912963.2017.1339037.

- ↑ Crawford, Nicholas G.; et al. (2015). "A phylogenomic analysis of turtles". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 83: 250–257. PMID 25450099. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2014.10.021.

- ↑ Guillon, Jean-Michel; et al. (2012). "A large phylogeny of turtles (Testudines) using molecular data". Contributions to Zoology. 81 (3): 147–158.

- ↑ Mikko's Phylogeny Archive Haaramo, Mikko (2007). "Testudinata – turtles, tortoises and terrapins". Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ↑ Tanke & Brett-Surman 2001, pp. 206–18

- ↑ Maugh II 2012

- ↑ Wings et al. 2012

- ↑ Gannon 2012

- ↑ Worthy, Trevor H. "Terrestrial Turtle Fossils from New Zealand Refloat Moa's Ark". Copeia. 2011 (1): 72–76. doi:10.2307/41261852.

- ↑ Valenzuela & Adams 2011

- ↑ Alderton 1986

- ↑ CDC 2007.

- ↑ GCTTS 2007.

- ↑ FDA 2012.

- ↑ "Turtles in the Pond". Creasey Mahan Nature Preserve. 2015-04-14. Retrieved 2016-06-13.

- ↑ Turtle Soup Recipe 1881.

- ↑ Smithsonian 2001.

- ↑ "Cayman Islands Turtle Farm". Archived from the original on December 19, 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-28.

- ↑ NOAA 2003.

- ↑ Chen, Chang & Lue 2009

- ↑ Dharmananda 2011

- ↑ Rhodin et al. 2011

- 1 2 Fish Farmer 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hylton 2007

- ↑ Cheung & Dudgeon 2006

- ↑ Amato 2007

- ↑ Pittman 2008

- ↑ World Chelonian Trust: Totals 2006.

- ↑ World Chelonian Trust: Destinations 2006.

- ↑ World Chelonian Trust: Observations 2006.

- ↑ "Help save turtles with a new tracking app". Australian Geographic. 23 May 2014. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

References

- Alderton, D. (1986). An Interpret Guide to Reptiles & Amphibians. London & New York: Salamander Books. ASIN B0010NVLQS.

- Amato, George (2007). A Conversation at the Museum of Natural History (video) (.flv). POV25. Retrieved November 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help). Filmmaker Eric Daniel Metzgar, the creator of the film The Chances of the World Changing, talks to George Amato, the director of conservation genetics at the American Museum of Natural History about turtle conservation and the relationship between evolution and extinction - Angier, N. (December 12, 2012). "All but Ageless, Turtles Face Their Biggest Threat: Humans". The New York Times.

- Anquetin, J. (2012). "Reassessment of the phylogenetic interrelationships of basal turtles (Testudinata)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 10 (1): 3–45. doi:10.1080/14772019.2011.558928.

- Barzyk, J.E. (November 1999). "Turtles in Crisis: The Asian Food Markets". Tortoise Trust. Retrieved November 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Benton, M.J. (2000). Vertebrate Paleontology (2nd ed.). London: Blackwell Science. ISBN 0-632-05614-2. (3rd ed. 2004 ISBN 0-632-05637-1)

- Brennessel, B. (2006). Diamonds in the Marsh: A Natural History of the Diamondback Terrapin. UPNE. ISBN 1584655364.

- "Turtles as Pets | CDC Healthy Pets Healthy People". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. October 2007. Archived from the original on 2012-08-05. Retrieved August 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Marshall Cavendish (2001). Endangered Wildlife and Plants of the World. ISBN 0761471944.

- Chen, T.-H.; Chang, H.-C.; Lue, K.-Y. (2009). "Unregulated Trade in Turtle Shells for Chinese Traditional Medicine in East and Southeast Asia: The Case of Taiwan". Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 8 (1): 11–18. doi:10.2744/CCB-0747.1.

- Cheung, S.M.; Dudgeon, D. (November–December 2006). "Quantifying the Asian turtle crisis: market surveys in southern China, 2000–2003". Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. 16 (7): 751–770. doi:10.1002/aqc.803.

- Chiari, Y.; Cahais, V.; Galtier, N.; Delsuc, F. (2012). "Phylogenomic analyses support the position of turtles as the sister group of birds and crocodiles (Archosauria)". BMC Biology. 10 (65): 65. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-10-65.

- Connor, Michael J. (2009). "CTTC's Turtle Trivia". California Turtle & Tortoise Club. Retrieved March 2009. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Crawford, Nicholas G.; Faircloth, Brant C.; McCormack, John E.; Brumfield, Robb T.; Winker, Kevin; Glen, Travis C. (2012). "More than 1000 ultraconserved elements provide evidence that turtles are the sister group to archosaurs" (PDF). Biology Letters. 8 (5): 783–6. PMC 3440978

. PMID 22593086. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2012.0331. Retrieved September 21, 2014.

. PMID 22593086. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2012.0331. Retrieved September 21, 2014. - Dharmananda, S. (2011). "Endangered Species Issues Affecting Turtles and Tortoises Used in Chinese Medicine: Appendix 1, 2, and 3". Institute for Traditional Medicine. Retrieved November 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Dubois, A.; Bour, R. (2010). "The distinction between family-series and class-series nomina in zoological nomenclature, with emphasis on the nomina created by Batsch (1788, 1789) and on the higher nomenclature of turtles" (PDF). Bonn zoological Bulletin. 57 (2): 149–171. ISSN 0006-7172.

- Ernst, C.H.; Lovich, J.E. (2009). Turtles of the United States and Canada. JHU Press. ISBN 9780801891212.

- Everhart, Mike (2012). "Marine Turtles". Oceans of Kansas Paleontology. Retrieved March 2009. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - "CFR - Code of Federal Regulations Title 21: FDA Regulation, Sec. 1240.62, page 678 part d1". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2012. Retrieved November 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Fergus, Charles (2007). Turtles: Wild Guide. Wild guide. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole books. p. viii. ISBN 9780811734202.

- "Turtle farms threaten rare species, experts say". Fish Farmer. 30 March 2007. Archived from the original on 18 February 2012. Retrieved November 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) Their source is an article by James Parham, Shi Haitao, and two other authors, published in Feb 2007 in the journal Conservation Biology - Doctors Foster & Smith educational staff (2012). "Anatomy and Diseases of the Shells of Turtles and Tortoises". Pet Education. Retrieved March 2009. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Gaffney, E.S. (1996). "The postcranial morphology of Meiolania platyceps and a review of the Meiolaniidae". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 229: 1–166.

- Gaffney, E.S.; Tong, H.; Meylan, P.A. (2006). "Evolution of the side-necked turtles: the families Bothremydidae, Euraxemydidae, and Araripemydidae". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 300: 1–698. doi:10.1206/0003-0090(2006)300[1:EOTSTT]2.0.CO;2.

- Gafney, E.; Hutchinson, H.; Jenkins, F.; Meeker, L. (1987). "Modern turtle origins; the oldest known cryptodire". Science. 237 (4812): 289–291. Bibcode:1987Sci...237..289G. PMID 17772056. doi:10.1126/science.237.4812.289.

- Gannon, Megan (October 31, 2012). "Jurassic turtle graveyard found in China". Livescience.com.

- "Isn't it against the law to sell turtles that are smaller than 4 inches?". Gulf Coast Turtle and Tortoise Society. November 2007. Retrieved November 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Hylton, H. (May 8, 2007). "Keeping U.S. Turtles Out of China". Time. Retrieved November 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)There is also a copy of the article at the TSA site. Articles by Peter Paul van Dijk are mentioned as the main source. - Hutchinson, J. (1996). "Introduction to Testudines: The Turtles". University of California Museum of Paleontology.

- Iwabe, Naoyuki; Hara, Yuichiro; Kumazawa, Yoshinori; Shibamoto, Kaori; Saito, Yumi; Miyata, Takashi; Katoh, Kazutaka (December 2004). "Sister group relationship of turtles to the bird-crocodilian clade revealed by nuclear DNA-coded proteins". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 22 (4): 810–813. PMID 15625185. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi075. Retrieved December 2010. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Iverson, J.B.; Kimerling, A. Jon; Kiester, A. Ross (1999). "List of All Families". Terra Cognita Laboratory, Geosciences Department of Oregon State University. Retrieved October 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Jackson, D. C. (2002). "Hibernating without oxygen: Physiological adaptations of the painted turtle". Journal of Physiology. 543 (Pt 3): 731–7. PMC 2290531

. PMID 12231634. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2002.024729.

. PMID 12231634. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2002.024729. - Joyce, Walter G. (2007). "Phylogenetic relationships of Mesozoic turtles" (PDF). Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History. 48 (1): 3–102. doi:10.3374/0079-032x(2007)48[3:promt]2.0.co;2.

- Katsu, Y.; Braun, E. L.; Guillette, L.J. Jr.; Iguchi, T. (March 2010). "From reptilian phylogenomics to reptilian genomes: analyses of c-Jun and DJ-1 proto-oncogenes". Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 127 (2–4): 79–93. PMID 20234127. doi:10.1159/000297715.

- King, G.L.; Berrow, S.D. (2009). Marine turtles in Irish waters (Supplement to the Irish Naturalists Journal). ISBN 978-0956970404.

- Laurin, Michel (1996). "Introduction to Procolophonoidea". University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved March 2009. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Lee, M.S.Y. (2001). "Molecules, morphology, and the monophyly of diapsid reptiles". Contributions to Zoology. 70 (1): 1–2.

- Chun Li; Xiao-Chun Wu; Rieppel, Olivier; Li-Ting Wang; Li-Jun Zhao (November 2008). "An ancestral turtle from the Late Triassic of southwestern China". Nature. 456 (7221): 497–501. Bibcode:2008Natur.456..497L. PMID 19037315. doi:10.1038/nature07533.

- Lyson, Tyler R.; Sperling, Erik A.; Heimberg, Alysha M.; Gauthier, Jacques A.; King, Benjamin L.; Peterson, Kevin J. (2012). "MicroRNAs support a turtle + lizard clade". Biology Letters. 8 (1): 104–107. PMC 3259949

. PMID 21775315. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2011.0477.

. PMID 21775315. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2011.0477. - Lyson, Tyler R.; Bever, Gabe S.; Bhullar, Bhart-Anjan S.; Joyce, Walter G.; Gauthier, Jacques A. (2010). "Transitional fossils and the origin of turtles". Biology Letters. 6 (6): 830–833. PMC 3001370

. PMID 20534602. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2010.0371.

. PMID 20534602. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2010.0371. - Mannen, Hideyuki; Li, Steven S.-L. (October 1999). "Molecular evidence for a clade of turtles". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 13 (1): 144–148. PMID 10508547. doi:10.1006/mpev.1999.0640.

- Maugh II, T.H. (May 18, 2012). "Researchers find fossil of a turtle that was size of a Smart car". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- Müller, Johannes (2004). "The relationships among diapsid reptiles and the influence of taxon selection". In Arratia, G; Wilson, M.V.H.; Cloutier, R. Recent Advances in the Origin and Early Radiation of Vertebrates. Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil. pp. 379–408. ISBN 978-3-89937-052-2.

- "Alligator Snapping Turtle". nationalgeographic.com. 2011. Retrieved August 2011. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - "NOAA'S Marine Forensics Laboratory". August 2003. Retrieved November 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Pittman, C. (October 9, 2008). "China Gobbling Up Florida Turtles". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- Priest, Toni E.; Franklin, Craig E. (December 2002). "Effect of Water Temperature and Oxygen Levels on the Diving Behavior of Two Freshwater Turtles: Rheodytes leukops and Emydura macquarii". Journal of Herpetology. 36 (4): 555–561. ISSN 0022-1511. JSTOR 1565924. doi:10.1670/0022-1511(2002)036[0555:EOWTAO]2.0.CO;2.

- Rieppel, O.; DeBraga, M. (1996). "Turtles as diapsid reptiles". Nature. 384 (6608): 453–5. Bibcode:1996Natur.384..453R. doi:10.1038/384453a0.

- Rhodin, A.G.J.; Walde, A.D.; Horne, B.D.; van Dijk, P.P.; Blanck, T.; Hudson, R., eds. (2011). Turtles in Trouble: The World's 25+ Most Endangered Tortoises and Freshwater Turtles—2011. Lunenburg, MA: Turtle Conservation Coalition.

- Roos, J.; Aggarwal, R.K.; Janke, A. (November 2007). "Extended mitogenomic phylogenetic analyses yield new insight into crocodylian evolution and their survival of the Cretaceous–Tertiary boundary". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 45 (2): 663–673. PMID 17719245. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2007.06.018.

- "Recipes from Another Time". Smithsonian. October 2001.

- Stone, Hector Burgos (2006). Amerika: Timeless World. Lulu.com. ISBN 1411681444.

- Tanke, D.H.; Brett-Surman, M.K. (2001). "Evidence of Hatchling and Nestling-Size Hadrosaurs (Reptilia: Ornithischia) from Dinosaur Provincial Park (Dinosaur Park Formation: Campanian), Alberta, Canada". In Tanke, D.H.; Carpenter, K. Mesozoic Vertebrate Life—New Research Inspired by the Paleontology of Philip J. Currie. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- "Old fashioned turtle soup recipe". The Household Cyclopedia of General Information. LoveToKnow Corp. 1881.

- Wings, Oliver; Rabi, Márton; Schneider, Jörg W.; Schwermann, Leonie; Ge Sun; Chang-Fu Zhou; Joyce, Walter G. (2012). "An enormous Jurassic turtle bone bed from the Turpan Basin of Xinjiang, China". Naturwissenschaften. 114 (11): 925. Bibcode:2012NW.....99..925W. doi:10.1007/s00114-012-0974-5.

- Valenzuela, N.; Adams, D.C. (2011). "Chromosome number and sex determination coevolve in turtles". Evolution. 65 (6): 1808–13. PMID 21644965. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01258.x.

- "Declared Turtle Trade From the United States – Totals". World Chelonian Trust. May 2006. Retrieved November 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - "Declared Turtle Trade From the United States: Destinations". World Chelonian Trust. May 2006. Retrieved November 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) (Major destinations: 13,625,673 animals to Hong Kong, 1,365,687 to the rest of the PRC, 6,238,300 to Taiwan, 3,478,275 to Mexico, and 1,527,771 to Japan, 945,257 to Singapore, and 596,966 to Spain.) - "Declared Turtle Trade From the United States: Observations". World Chelonian Trust. May 2006. Retrieved November 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Zardoya, R.; Meyer, A. (1998). "Complete mitochondrial genome suggests diapsid affinities of turtles". Proceedigns of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (24): 14226–14231. Bibcode:1998PNAS...9514226Z. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 24355

. PMID 9826682. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.24.14226.

. PMID 9826682. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.24.14226.

Further reading

- Pritchard, Peter Charles Howard (1979). Encyclopedia of turtles. Neptune, NJ: T.F.H. Publications. ISBN 0-87666-918-6.

External links

| The Wikibook Animal Care has a page on the topic of: Turtle |

- Chelonian studbook Collection and display of the weights/sizes of captive turtles

- Biogeography and Phylogeny of the Chelonia (taxonomy, maps)

- New Scientist article (including video) on how the turtle evolved its shell

_white_background.jpg)

_flipped.jpg)

_white_background.jpg)

_white_background.jpg)

_white_background.jpg)

_white_background.jpg)

_flipped.jpg)

_white_background.jpg)