Chebyshev polynomials

In mathematics the Chebyshev polynomials, named after Pafnuty Chebyshev,[1] are a sequence of orthogonal polynomials which are related to de Moivre's formula and which can be defined recursively. One usually distinguishes between Chebyshev polynomials of the first kind which are denoted Tn and Chebyshev polynomials of the second kind which are denoted Un. The letter T is used because of the alternative transliterations of the name Chebyshev as Tchebycheff, Tchebyshev (French) or Tschebyschow (German).

The Chebyshev polynomials Tn or Un are polynomials of degree n and the sequence of Chebyshev polynomials of either kind composes a polynomial sequence.

The Chebyshev polynomials Tn are polynomials with the largest possible leading coefficient, but subject to the condition that their absolute value on the interval [−1,1] is bounded by 1. They are also the extremal polynomials for many other properties.[2]

Chebyshev polynomials are important in approximation theory because the roots of the Chebyshev polynomials of the first kind, which are also called Chebyshev nodes, are used as nodes in polynomial interpolation. The resulting interpolation polynomial minimizes the problem of Runge's phenomenon and provides an approximation that is close to the polynomial of best approximation to a continuous function under the maximum norm. This approximation leads directly to the method of Clenshaw–Curtis quadrature.

In the study of differential equations they arise as the solution to the Chebyshev differential equations

and

for the polynomials of the first and second kind, respectively. These equations are special cases of the Sturm–Liouville differential equation.

Definition

The Chebyshev polynomials of the first kind are defined by the recurrence relation

The ordinary generating function for Tn is

the exponential generating function is

The generating function relevant for 2-dimensional potential theory and multipole expansion is

The Chebyshev polynomials of the second kind are defined by the recurrence relation

The ordinary generating function for Un is

the exponential generating function is

Trigonometric definition

The Chebyshev polynomials of the first kind can be defined as the unique polynomials satisfying

or, in other words, as the unique polynomials satisfying

for n = 0, 1, 2, 3, ... which is a variant (equivalent transpose) of Schröder's equation, viz. Tn(x) is functionally conjugate to nx, codified in the nesting property below. Further compare to the spread polynomials, in the section below.

The polynomials of the second kind satisfy:

or

which is structurally quite similar to the Dirichlet kernel Dn(x):

That cos nx is an nth-degree polynomial in cos x can be seen by observing that cos nx is the real part of one side of de Moivre's formula. The real part of the other side is a polynomial in cos x and sin x, in which all powers of sin x are even and thus replaceable through the identity cos2 x + sin2 x = 1. By the same reasoning, sin nx is the imaginary part of the polynomial, in which all powers of sin x are odd and thus, if one is factored out, the remaining can be replaced to create a (n-1)th-degree polynomial in cos x.

The identity is quite useful in conjunction with the recursive generating formula, inasmuch as it enables one to calculate the cosine of any integral multiple of an angle solely in terms of the cosine of the base angle.

Evaluating the first two Chebyshev polynomials,

and

one can straightforwardly determine that

and so forth.

Two immediate corollaries are the composition identity (or nesting property specifying a semigroup)

and the expression of complex exponentiation in terms of Chebyshev polynomials: given z = a + bi,

Pell equation definition

The Chebyshev polynomials can also be defined as the solutions to the Pell equation

in a ring R[x].[3] Thus, they can be generated by the standard technique for Pell equations of taking powers of a fundamental solution:

Products of Chebyshev polynomials

When working with Chebyshev polynomials quite often products of two of them occur. These products can be reduced to combinations of Chebyshev polynomials with lower or higher degree and concluding statements about the product are easier to make. It shall be assumed that in the following the index m is greater than or equal to the index n and n is not negative. For Chebyshev polynomials of the first kind the product expands to

which is an analogy to the addition theorem

with the identities

For n = 1 this results in the already known recurrence formula, just arranged differently, and with n = 2 it forms the recurrence relation for all even or all odd Chebyshev polynomials (depending on the parity of the lowest m) which allows to design functions with prescribed symmetry properties. Three more useful formulas for evaluating Chebyshev polynomials can be concluded from this product expansion:

For Chebyshev polynomials of the second kind with products may be written as:

for m ≥ n.

By this, like above, with n = 2 the recurrence formula of Chebyshev polynomials of the second kind forms for both types of symmetry to

depending on whether m starts with 2 or 3.

Relations between Chebyshev polynomials of the first and second kinds

The Chebyshev polynomials of the first and second kinds correspond to a complementary pair of Lucas sequences Ṽn(P,Q) and Ũn(P,Q) with parameters P = 2x and Q = 1:

It follows that they also satisfy a pair of mutual recurrence equations:

The Chebyshev polynomials of the first and second kinds are also connected by the following relations:

The recurrence relationship of the derivative of Chebyshev polynomials can be derived from these relations:

This relationship is used in the Chebyshev spectral method of solving differential equations.

Turán's inequalities for the Chebyshev polynomials are

The integral relations are

where integrals are considered as principal value.

Explicit expressions

Different approaches to defining Chebyshev polynomials lead to different explicit expressions such as:

with inverse

where the prime at the sum symbol indicates that the contribution of j = 0 needs to be halved if it appears.

where 2F1 is a hypergeometric function.

Properties

Symmetry

That is, Chebyshev polynomials of even order have even symmetry and contain only even powers of x. Chebyshev polynomials of odd order have odd symmetry and contain only odd powers of x.

Roots and extrema

A Chebyshev polynomial of either kind with degree n has n different simple roots, called Chebyshev roots, in the interval [−1,1]. The roots of the Chebyshev polynomial of the first kind are sometimes called Chebyshev nodes because they are used as nodes in polynomial interpolation. Using the trigonometric definition and the fact that

one can easily prove that the roots of Tn are

Similarly, the roots of Un are

The extrema of Tn on the interval −1 ≤ x ≤ 1 are located at

One unique property of the Chebyshev polynomials of the first kind is that on the interval −1 ≤ x ≤ 1 all of the extrema have values that are either −1 or 1. Thus these polynomials have only two finite critical values, the defining property of Shabat polynomials. Both the first and second kinds of Chebyshev polynomial have extrema at the endpoints, given by:

Differentiation and integration

The derivatives of the polynomials can be less than straightforward. By differentiating the polynomials in their trigonometric forms, it's easy to show that:

The last two formulas can be numerically troublesome due to the division by zero (0/0 indeterminate form, specifically) at x = 1 and x = −1. It can be shown that:

The second derivative of the Chebyshev polynomial of the first kind is

which, if evaluated as shown above, poses a problem because it is indeterminate at x = ±1. Since the function is a polynomial, (all of) the derivatives must exist for all real numbers, so the taking to limit on the expression above should yield the desired value:

where only x = 1 is considered for now. Factoring the denominator:

Since the limit as a whole must exist, the limit of the numerator and denominator must independently exist, and

The denominator (still) limits to zero, which implies that the numerator must be limiting to zero, i.e. Un − 1(1) = nTn(1) = n which will be useful later on. Since the numerator and denominator are both limiting to zero, L'Hôpital's rule applies:

The proof for x = −1 is similar, with the fact that Tn(−1) = (−1)n being important.

Indeed, the following, more general formula holds:

This latter result is of great use in the numerical solution of eigenvalue problems.

where the prime at the summation symbols means that the term contributed by k = 0 is to be halved, if it appears.

Concerning integration, the first derivative of the Tn implies that

and the recurrence relation for the first kind polynomials involving derivatives establishes that

and

Orthogonality

Both Tn and Un form a sequence of orthogonal polynomials. The polynomials of the first kind are orthogonal with respect to the weight

on the interval [−1,1], i.e. we have:

This can be proven by letting x = cos θ and using the defining identity Tn(cos θ) = cos nθ.

Similarly, the polynomials of the second kind are orthogonal with respect to the weight

on the interval [−1,1], i.e. we have:

(Note that the measure √1 − x2 dx is, to within a normalizing constant, the Wigner semicircle distribution.)

The Tn also satisfy a discrete orthogonality condition:

where the xk are the N Chebyshev nodes (see above) of TN(x)

For the polynomials of the second kind and with the same Chebyshev nodes xk there are similar sums:

and without the weight function:

Based on the N zeros of the Chebyshev polynomial of the second kind UN(x)

a different sum can be constructed

and again without the weight function:

Minimal ∞-norm

For any given n ≥ 1, among the polynomials of degree n with leading coefficient 1,

is the one of which the maximal absolute value on the interval [−1, 1] is minimal.

This maximal absolute value is

and |f(x)| reaches this maximum exactly n + 1 times at

Let's assume that wn(x) is a polynomial of degree n with leading coefficient 1 with maximal absolute value on the interval [−1,1] less than 1 / 2n − 1.

Define

Because at extreme points of Tn we have

From the intermediate value theorem, fn(x) has at least n roots. However, this is impossible, as fn(x) is a polynomial of degree n − 1, so the fundamental theorem of algebra implies it has at most n − 1 roots.

Remark: By the Equioscillation theorem, among all the polynomials of degree ≤ n, the polynomial f minimizes ||f||∞ on [−1,1] if and only if there are n + 2 points −1 ≤ x0 < x1 < ... < xn + 1 ≤ 1 such that |f(xi)| = ||f||∞.

Of course, the null polynomial on the interval [−1,1] can be approach by itself and minimizes the ∞-norm.

Above, however, |f| reaches its maximum only n + 1 times because we are searching for the best polynomial of degree n ≥ 1 (therefore the theorem evoked previously cannot be used).

Other properties

The Chebyshev polynomials are a special case of the ultraspherical or Gegenbauer polynomials, which themselves are a special case of the Jacobi polynomials:

For every nonnegative integer n, Tn(x) and Un(x) are both polynomials of degree n. They are even or odd functions of x as n is even or odd, so when written as polynomials of x, it only has even or odd degree terms respectively. In fact,

and

The leading coefficient of Tn is 2n − 1 if 1 ≤ n, but 1 if 0 = n.

Tn are a special case of Lissajous curves with frequency ratio equal to n.

Several polynomial sequences like Lucas polynomials (Ln), Dickson polynomials (Dn), Fibonacci polynomials (Fn) are related to Chebyshev polynomials Tn and Un.

The Chebyshev polynomials of the first kind satisfy the relation

which is easily proved from the product-to-sum formula for the cosine. The polynomials of the second kind satisfy the similar relation

(with the convention U−1 ≡ 0).

Similar to the formula

we have the analogous formula

- .

For x ≠ 0,

and

- ,

which follows from the fact that this holds by definition for x = eiθ.

Let

- .

Then Cn(x) and Cm(x) are commuting polynomials:

- ,

as is evident in the Abelian nesting property specified above.

Generalized Chebyshev polynomials

The generalized Chebyshev polynomials Ta are defined by

where a is not necessarily an integer, and 2F1(a, b; c; z) is the Gaussian hypergeometric function. They have the power series expansion

Examples

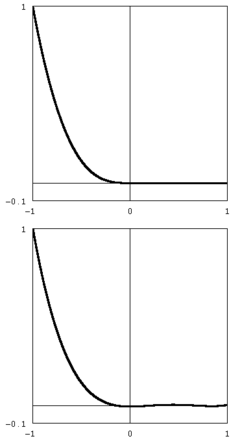

First kind

).svg.png)

The first few Chebyshev polynomials of the first kind are ![]() A028297

A028297

Second kind

).svg.png)

The first few Chebyshev polynomials of the second kind are ![]() A053117

A053117

As a basis set

In the appropriate Sobolev space, the set of Chebyshev polynomials form an orthonormal basis, so that a function in the same space can, on −1 ≤ x ≤ 1 be expressed via the expansion:[4]

Furthermore, as mentioned previously, the Chebyshev polynomials form an orthogonal basis which (among other things) implies that the coefficients an can be determined easily through the application of an inner product. This sum is called a Chebyshev series or a Chebyshev expansion.

Since a Chebyshev series is related to a Fourier cosine series through a change of variables, all of the theorems, identities, etc. that apply to Fourier series have a Chebyshev counterpart.[4] These attributes include:

- The Chebyshev polynomials form a complete orthogonal system.

- The Chebyshev series converges to f(x) if the function is piecewise smooth and continuous. The smoothness requirement can be relaxed in most cases — as long as there are a finite number of discontinuities in f(x) and its derivatives.

- At a discontinuity, the series will converge to the average of the right and left limits.

The abundance of the theorems and identities inherited from Fourier series make the Chebyshev polynomials important tools in numeric analysis; for example they are the most popular general purpose basis functions used in the spectral method,[4] often in favor of trigonometric series due to generally faster convergence for continuous functions (Gibbs' phenomenon is still a problem).

Example 1

Consider the Chebyshev expansion of log(1 + x). One can express

One can find the coefficients an either through the application of an inner product or by the discrete orthogonality condition. For the inner product,

which gives

Alternatively, when you cannot evaluate the inner product of the function you are trying to approximate, the discrete orthogonality condition gives an often useful result for approximate coefficients,

where δij is the Kronecker delta function and the xk are the N Gauss–Chebyshev zeros of TN(x):

For any N, these approximate coefficients provide an exact approximation to the function at xk with a controlled error between those points. The exact coefficients are obtained with N = ∞, thus representing the function exactly at all points in [−1,1]. The rate of convergence depends on the function and its smoothness.

This allows us to compute the approximate coefficients an very efficiently through the discrete cosine transform

Example 2

To provide another example:

Partial sums

The partial sums of

are very useful in the approximation of various functions and in the solution of differential equations (see spectral method). Two common methods for determining the coefficients an are through the use of the inner product as in Galerkin's method and through the use of collocation which is related to interpolation.

As an interpolant, the N coefficients of the (N − 1)th partial sum are usually obtained on the Chebyshev–Gauss–Lobatto[5] points (or Lobatto grid), which results in minimum error and avoids Runge's phenomenon associated with a uniform grid. This collection of points corresponds to the extrema of the highest order polynomial in the sum, plus the endpoints and is given by:

Polynomial in Chebyshev form

An arbitrary polynomial of degree N can be written in terms of the Chebyshev polynomials of the first kind.[6] Such a polynomial p(x) is of the form

Polynomials in Chebyshev form can be evaluated using the Clenshaw algorithm.

Spread polynomials

The spread polynomials are in a sense equivalent to the Chebyshev polynomials of the first kind, but enable one to avoid square roots and conventional trigonometric functions in certain contexts, notably in rational trigonometry.

Shifted Chebyshev polynomials

Shifted Chebyshev polynomials of the first kind are defined as

Note that when the argument of the Chebyshev polynomial is in the range of 2x − 1 ∈ [−1,1] the argument of the shifted Chebyshev polynomial is x ∈ [0,1]. Similarly, one can define shifted polynomials for generic intervals [a,b].

See also

- Chebyshev filter

- Chebyshev cube root

- Dickson polynomials

- Legendre polynomials

- Hermite polynomials

- Romanovski polynomials

- Chebyshev rational functions

- Approximation theory

- The Chebfun system

- Discrete Chebyshev transform

- Markov brothers' inequality

Notes

- ↑ Chebyshev polynomials were first presented in: P. L. Chebyshev (1854) "Théorie des mécanismes connus sous le nom de parallélogrammes," Mémoires des Savants étrangers présentés à l’Académie de Saint-Pétersbourg, vol. 7, pages 539–586.

- ↑ Rivlin, Theodore J. The Chebyshev polynomials. Pure and Applied Mathematics. Wiley-Interscience [John Wiley & Sons], New York-London-Sydney,1974. Chapter 2, "Extremal Properties", pp. 56--123.

- ↑ Jeroen Demeyer Diophantine Sets over Polynomial Rings and Hilbert's Tenth Problem for Function Fields, Ph.D. theses (2007), p.70.

- 1 2 3 Boyd, John P. (2001). Chebyshev and Fourier Spectral Methods (PDF) (second ed.). Dover. ISBN 0-486-41183-4.

- ↑ Chebyshev Interpolation: An Interactive Tour

- ↑ For more information on the coefficients, see: Mason, J. C. and Handscomb, D. C. (2002). Chebyshev Polynomials. Taylor & Francis.

References

- Abramowitz, Milton; Stegun, Irene Ann, eds. (1983) [June 1964]. "Chapter 22". Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables. Applied Mathematics Series. 55 (Ninth reprint with additional corrections of tenth original printing with corrections (December 1972); first ed.). Washington D.C.; New York: United States Department of Commerce, National Bureau of Standards; Dover Publications. p. 773. ISBN 978-0-486-61272-0. LCCN 64-60036. MR 0167642. LCCN 65-12253.

- Dette, Holger (1995). "A Note on Some Peculiar Nonlinear Extremal Phenomena of the Chebyshev Polynomials". Proceedings of the Edinburgh Mathematical Society. 38 (2): 343–355. doi:10.1017/S001309150001912X.

- Elliott, David (1964). "The evaluation and estimation of the coefficients in the Chebyshev Series expansion of a function". Math. Comp. 18 (86): 274–284. MR 0166903. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-1964-0166903-7.

- Eremenko, A.; Lempert, L. (1994). "An Extremal Problem For Polynomials]" (PDF). Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society. 122 (1): 191–193. MR 1207536. doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-1994-1207536-1.

- Hernandez, M. A. (2001). "Chebyshev's approximation algorithms and applications". Comp. Math. Applic. 41: 433–445.

- Mason, J. C. (1984). "Some properties and applications of Chebyshev polynomial and rational approximation". Lect. Not. Math. 1105: 27–48. doi:10.1007/BFb0072398.

- Mason, J. C.; Handscomb, D. C. (2002). Chebyshev Polynomials. Taylor & Francis.

- Mathar, R. J. (2006). "Chebyshev series expansion of inverse polynomials". J. Comput. Appl. Math. 196: 596–607. doi:10.1016/j.cam.2005.10.013.

- Koornwinder, Tom H.; Wong, Roderick S. C.; Koekoek, Roelof; Swarttouw, René F. (2010), "Orthogonal Polynomials", in Olver, Frank W. J.; Lozier, Daniel M.; Boisvert, Ronald F.; Clark, Charles W., NIST Handbook of Mathematical Functions, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521192255, MR 2723248

- Remes, Eugene. "On an Extremal Property of Chebyshev Polynomials" (PDF).

- Salzer, Herbert E. (1976). "Converting interpolation series into Chebyshev Series by Recurrence Formulas". Math. Comp. 30 (134): 295–302. MR 0395159. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-1976-0395159-3.

- Scraton, R. E. (1969). "The Solution of integral equations in Chebyshev series". Math. Comput. 23 (108): 837–844. MR 0260224. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-1969-0260224-4.

- Smith, Lyle B. (1966). "Algorithm 277, Computation of Chebyshev series coefficients". Comm. ACM. 9 (2): 86–87. doi:10.1145/365170.365195.

- Suetin, P. K. (2001) [1994], "C/c021940", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

External links

- Weisstein, Eric Wolfgang. "Chebyshev Polynomial of the First Kind". MathWorld.

- Module for Chebyshev Polynomials by John H. Mathews

- Chebyshev Interpolation: An Interactive Tour, includes illustrative Java applet.

- Numerical Computing with Functions: The Chebfun Project

- Is there an intuitive explanation for an extremal property of Chebyshev polynomials?