Charlestown, Boston

| Charlestown | ||

|---|---|---|

| Neighborhood of Boston | ||

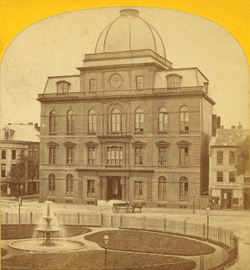

|

Charlestown's former City Hall | ||

| ||

| Motto: Liberty A Trust To Be Transmitted To Posterity | ||

| Coordinates: 42°22′31″N 71°03′52″W / 42.37528°N 71.06444°WCoordinates: 42°22′31″N 71°03′52″W / 42.37528°N 71.06444°W | ||

| Country | United States | |

| State | Massachusetts | |

| City | Boston | |

| Settled | 1628 | |

| Incorporated (Town) | 1628 | |

| Incorporated (City) | 1847 | |

| Annexed by Boston | 1874 | |

| Time zone | Eastern (UTC-5) | |

| • Summer (DST) | Eastern (UTC-4) | |

| Zip Code | 02129 | |

| Area code(s) | 617/857 | |

Charlestown is the oldest neighborhood in Boston, Massachusetts, United States.[1] Originally called Mishawum by the Massachusett, it is located on a peninsula north of the Charles River, across from downtown Boston, and also adjoins the Mystic River and Boston Harbor. Charlestown was laid out in 1629 by engineer Thomas Graves, one of its early settlers, in the reign of Charles I of England. It was originally a separate town and the first capital of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Charlestown became a city in 1848 and was annexed by Boston on January 5, 1874. With that, it also switched from Middlesex County, to which it had belonged since 1643, to Suffolk County. It has had a substantial Irish American population since the migration of Irish people during the Great Irish Famine of the 1840s. Since the late 1980s the neighborhood has changed dramatically because of its proximity to downtown and its colonial architecture. A mix of Yuppie and Upper-middle class gentrification has influenced much of the area, as it has in many of Boston's neighborhoods, but Charlestown still maintains a strong Irish American population and "Townie" identity.

In the 21st century, Charlestown's diversity has expanded dramatically, along with growing rates of the very poor and very wealthy. Today Charlestown is a largely residential neighborhood, with much housing near the waterfront, overlooking the Boston skyline. Charlestown is home to many historic sites, hospitals and organizations, with easy access from the Orange Line Community College stop or I-93 expressway.

History

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1800 | 2,751 | — | |

| 1810 | 4,959 | 80.3% | |

| 1820 | 6,591 | 32.9% | |

| 1830 | 8,783 | 33.3% | |

| 1840 | 11,484 | 30.8% | |

| 1850 | 17,216 | 49.9% | |

| 1860 | 25,065 | 45.6% | |

| 1870 | 28,323 | 13.0% | |

Thomas and Jane Walford[2] were the original English settlers of the peninsula between the Charles and the Mystic. They were given a grant by Sir Robert Gorges, with whom they had settled at Wessagusset (Weymouth) in September 1623 and arrived at what they called Mishawaum in 1624. John Endicott, first governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony, sent William, Richard and Ralph Sprague to Mishawaum to lay out a settlement. Thomas Walford, acting as an interpreter with the Massachusetts Indians, negotiated with the local sachem Wonohaquaham for Endicott and his people to settle there. Although Walford had a virtual monopoly on the region's available furs, he welcomed the newcomers and helped them in any way he could, unaware that his Episcopalian religious beliefs would cause him to be banished from Massachusetts to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, within three years.

Originally a Puritan English city during the Colonial era, Charlestown proper was founded in 1628 and settled July 4, 1629, by Thomas Graves, Increase Nowell, Simon Hoyt, the Rev. Francis Bright, Ralph, Richard and William Sprague, and about 100 others who preceded the Great Migration. John Winthrop's company stopped here for some time in 1630, before deciding to settle across the Charles River at Boston.

The territory of Charlestown was initially quite large. From it, Woburn was separated in 1642,[3] Melrose and Malden in 1649,[4] Stoneham in 1725,[5] and Somerville in 1842. Everett, Burlington, Medford, Arlington and Cambridge also acquired areas originally allocated to Charlestown.[6]

On June 17, 1775, the Charlestown Peninsula was the site of the Battle of Bunker Hill, named for a hill at the northwest end of the peninsula near Charlestown Neck. British troops unloaded at Moulton’s Point[3] and much of the battle took place on Breed's Hill, which overlooked the harbor from about 400 yards off the southern end of the peninsula. The town, including its wharves and dockyards, was almost completely destroyed[7] during the battle by the British.[3] The town was not appreciably rebuilt until the end of hostilities but, in 1786, the first bridge across the Charles River connected Boston with Charlestown.[3] An 87-acre (35 ha) Navy Yard was established in 1800; Charlestown State Prison opened in 1805.[3] The Bunker Hill Monument was erected between 1827 and 1843 using Quincy granite brought to the site by a combination of purpose-built railway and barge. Notable businesses included the Bunker Hill Breweries (1821) and Schrafft's candy company (1861).

Around the 1860s an influx of Irish immigrants arrived in Charlestown. The area long remained an Irish and Catholic stronghold similar to South Boston, Somerville, and Dorchester, to the extent that the informal demonym "Townie" continues to imply the working-class Irish, as opposed to newer immigrants.

During the Civil War, over 26,000 men joined the Union Army and Navy at the Navy Yard, which was also responsible for constructing some of the most famous vessels of the conflict: the Merrimack, the Hartford, and the Monadnock.[8] Following the war, the city commissioned Martin Milmore to construct its civil war memorial, dedicated in 1872[3] and still standing in the community's Training Field.[9]

The city developed a water supply from the Mystic Lakes[10] and, on October 7, 1873, a vote was held to determine whether Charlestown should leave Middlesex County and join Boston as part of Suffolk County. Out of its 32,040 residents,[7] 2240 voted in support of the merger and 1947 opposed. Boston residents also approved the question, 5,960–1,868.[11] Charlestown's separate city government was dissolved the next year.[7]

During the early 1960s, the city initiated plans to demolish and redevelop sixty percent of the housing in Charlestown.[12] In 1963, the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA) held a town meeting to discuss their development plans with the community. The BRA's dealings with Boston's West End had created an atmosphere of distrust towards urban renewal in Boston, and Charlestown residents opposed the plan by an overwhelming majority. By 1965, the plan had been reduced to tearing down only eleven percent of the neighborhood, as well as the removal of the elevated rail tracks.[13]

Throughout the 1960s until the mid-1990s, Charlestown was infamous for its Irish Mob presence. Charlestown's McLaughlin Brothers were involved in a gang war with neighboring Somerville's Winter Hill Gang, during the Irish Mob Wars of the 1960s. In the late 1980s, however, Charlestown underwent a massive Yuppie gentrification process similar to that of the South End. Drawn to its proximity to downtown and its colonial, red-brick, row-house housing stock, similar to that of Beacon Hill, many Yuppie and upper-middle class professionals moved to the neighborhood. In the late 1990s, additional gentrification took place, similar to that in neighboring Somerville. Today the neighborhood is a mix of Yuppies, upper-middle and middle-class residents, housing projects, and a large working class Irish-American demographic and culture that is still predominant.

One of the oldest neighborhoods of Boston, Charlestown is home to the Bunker Hill Monument and historic Charlestown Navy Yard.[14] Charlestown today is a mainly residential neighborhood with an institutional presence. Major institutions include Bunker Hill Community College, Spaulding Rehabilitation Center, and a facility of Massachusetts General Hospital. The Navy Yard is now a popular national park that marks the southern edge of the neighborhood. The waterfront has two marinas, Constitution Marina and Shipyard Quarters Marina.

Geography

Charlestown is located north of downtown Boston on a peninsula extending southeastward between the Charles River and the Mystic River. The geographic extent of the neighborhood has changed dramatically from its colonial ancestor. Landfill operations have expanded much of Boston, lowering hills, and have expanded Charlestown, eliminating the narrow Charlestown Neck that connected the northwest end of the Charlestown Peninsula to the mainland. The original territory also included present-day Somerville, which was incorporated as a separate town in 1842, and the northern part of Arlington. At the time, the Charlestown Peninsula was urbanizing, while Somerville was still largely rural.

City Square in the southern part of Charlestown is the location of the historic city hall. It is also the terminus of the Charlestown Bridge and the former Warren Bridge, and was formerly a stop on the Charlestown Elevated. The Central Artery was built between 1951 and 1954, routing elevated ramps through City Square. The Central Artery North Area (CANA) project moved these underground, into the City Square Tunnel, making way for a revitalized surface park.

Thompson Square is located at the confluence of Main Street, Dexter Row, Green Street, and Austin Street. It was also formerly a stop on the Charlestown Elevated.

Demographics

According to the U.S Census Bureau in its 2007–2011 report, the population of Charlestown is 16,685, comprising 7,843 males and 8,842 females. The largest age group is 25 to 29 years (14.6%), the second largest is 30 to 34 (12.3%), and the third largest is 35 to 39 (9.7%).

The majority of the population is white at 12,587 (75.4%). Minorities include Black or African at 1,227 (7.4%), Asian at 1,253 (7.5%), Hispanic or Latino at 1,227 (7.4%), and those of two or more races at 371 (2.2%). In recent years, the percentage of minorities living in Charlestown has increased from 4.9% of the population in 1990 to 23.5% in 2010. The population consists of 15.9% who are foreign born, 48.5% of whom are naturalized citizens, and 51.5% who are not.

The median household income is $89,017, and the median family income is $100,725. The median income for whites is $103,652; that for Blacks or African Americans, $12,143; for Hispanics or Latinos, $30,833; for Asians, $61,875; and for others, $16,876.

17% percent of the population and 37% of the children live below the Federal Poverty Line. Of married couples, 32.4% are living in poverty with families. Of male householders with no wife present, 3.4% live in poverty; and of female householders with no husband, 64.2% live in poverty.

Housing policy

The Bunker Hill Public Housing has divided Bunker Hill Street into two Charlestowns. The housing development company Corcoran-SunCal plans to make changes and replace the 1,100 affordable units. "While preserving the affordable units, Corcoran-SunCal will also create approximately 1,700 additional market and moderate-rate units". This company will allow all current residents to move back into the housing complex. According to Project Manager Sarah Barnet, "by creating both affordable and market rate housing at the site the area will become a more thriving section of the neighborhood, a destination area for residents from all over a Charlestown and a high quality place for people to live".[15]

Transportation

According to the Census from 2010–2014, 53.7% of the population will drive to work and 30.0% will take a some form of public transportation to get to their jobs. Charlestown is accessible by several forms of public transportation, including train, bus and ferry. The train transportation is the MBTA Orange Line. The major stop is Community College, located near Bunker Hill Community College. The 93 bus goes from Sullivan Station, downtown via Bunker Hill Street and Haymarket Station. The 92 bus runs from Assembly Square Mall, downtown via Sullivan Square Station, Main Street and Haymarket Station. Charlestown is also accessible via the Charlestown Navy Yard Ferry Terminal.

Hospitals and healthcare

- Mass General: Charlestown Healthcare Center – MGH Charlestown Healthcare Center is a part of Massachusetts General Hospital. MGH Charlestown has been providing the Charlestown community since 1968. MGH Charlestown works closely with local school and community organizations to provide programs that truly benefit Charlestown's culturally diverse populations.

- Spaulding Rehabilitation Center – outpatient facility.

- NEW Health Charlestown – The city of Charlestown has been hit hard with the opioid crisis. While reading an article in the Boston Globe online data base, it explains that Charlestown has been hit nearly twice as hard with deaths related to substance abuse than any other Massachusetts town. To accommodate this crisis they recently opened a new clinic called NEW Health Charlestown. This facility will also join an existing clinic in the neighborhood run by Massachusetts General Hospital. This new independent facility will have a staff of 26 primary care physicians from dentist to substance abuse counselors.

Government and infrastructure

The Massachusetts Department of Correction operated the Charlestown State Prison until its closure in 1955. The former prison site is occupied by Bunker Hill Community College.[16]

The Boston Navy Yard was located in Charlestown from 1801 until it was closed in 1974.

The United States Postal Service operates the Charlestown Post Office.[17]

Charlestown is well served by public transportation. On the MBTA Orange Line, the Community College station serves the center of the town and the Sullivan Square station serves the area near the Charlestown Neck. Two bus lines serve Charlestown. Both routes start at Sullivan Square and travel to the Financial District. The 93 bus travels along Bunker Hill Street,[18] and the 92 bus travels along Main Street.[19] The MBTA also operates a ferry between the Charlestown Navy Yard Ferry Terminal and Long Wharf (near the New England Aquarium),[20] making this a popular choice among both commuters and tourists.[21]

Places of interest

Charlestown has many places of historical interest, some of which are included along the northern end of Boston's Freedom Trail. The Freedom Trail ends at the Bunker Hill Monument commemorating the famous Battle of Bunker Hill. The USS Constitution, the oldest commissioned vessel in the US Navy, is docked in the Charlestown Navy Yard. Charlestown was also the location from which Paul Revere began his famous "midnight ride" before the Battles of Lexington and Concord. A restaurant opened in 1780 and still in operation, Warren Tavern, claims to have been one of Revere's favorite taverns. Of Charlestown's churches, St. Mary's (1887–1893) is considered one of the masterpieces of Patrick Keely. In St. John's Episcopal Church, on Devens Street, the central stained glass above the altar is a notable work of William James McPherson, a Boston designer who later designed the stained glass for the Connecticut State Capitol.[22]

Education

Boston's Charlestown neighborhood is served by the Boston Public Schools system. There are also private educational institutions within the neighborhood.

Primary and secondary schools

- Harvard/Kent Elementary School[23]

- Clarence R. Edwards Middle School[24]

- Warren-Prescott K–8 School[25]

- Charlestown High School[26]

Colleges and universities

- Bunker Hill Community College's main campus[16]

- MGH Institute of Health Professions, a graduate school founded by Massachusetts General Hospital

Public libraries

Boston Public Library operates the Charlestown Branch. The library first opened in the Warren Institution for Savings building on January 7, 1862. The library moved to a larger space in the new Charlestown City Hall in 1869. In 1913 the branch moved to the intersection of Monument Avenue and Monument Square, in proximity to the Bunker Hill Monument. The branch moved to its current location in 1970.[27]

Leisure activities

Bunker Hill Monument

The Bunker Hill Monument is located at Monument Square. It marks the first major battle of the American Revolution, on June 17, 1775. The height of the monument is 221 feet. Visitors can climb the 294 steps to reach the top.

USS Constitution and the Charlestown Navy Yard

The USS Constitution is the oldest warship in the world still afloat. It was launched in 1797, one of six ships built by order of President George Washington to protect maritime interests. The location of the USS Constitution and Charlestown Navy Yard is at 1 Constitution Road. The Navy Yard is today under the National Park Service, an organization that helps preserve history.

Warren Tavern

The Warren Tavern first opened in 1780.[28] It is located at 2 Pleasant Street. The building was one of the first built after the Battle of Bunker Hill. The Tavern took its name from Dr. Joseph Warren, American Patriot who played a key role in the American Revolution and was killed in the Battle of Bunker Hill. It was Warren who directed Paul Revere and William Dawes to send the message to Samuel Adams and John Hancock that the British were setting out to raid the town of Concord. Warren's friend Captain Eliphelet Newell decided to build a tavern named after his friend. George Washington visited the tavern when he came to Massachusetts to visit his friend Benjamin Frothingham. After the Tavern was closed in 1813, the building served other purposes, and then was saved in the 1970s. The Tavern was reopened in 1972.

Constitution Yacht Charter

The Constitution Yacht Charter is located on Boston Harbor.

In popular culture

The 1998 independent drama Monument Ave. directed by Ted Demme stars Denis Leary as Bobby O'Grady; an Irish-American criminal who becomes conflicted when the code of silence puts his loyalty and sense of self-preservation to the test after his two young and close cousins, also fellow criminals, are brutally gunned down by their boss.

Charlestown was also the setting for the 2010 action-thriller The Town, directed by and starring Cambridge native Ben Affleck, which follows the lives of a group of Boston bank robbers and the law enforcement personnel attempting to stop them.[29]

The Bunker Hill housing development, an area known for its crime and drug use, is featured on the front cover of Blood for Blood's album Serenity.

Other movies that were set in or filmed in Charlestown include:[30]

- Townies (2009), a short film about Mickey Callaghan's release from prison.

- Martin Scorsese filmed portions of The Departed (2006) starring Jack Nicholson and Matt Damon in Charlestown (standing in for the South End)

- The Clint Eastwood film Mystic River (2003) was filmed, in part, in Charlestown.

- Scenes in Celtic Pride (1999) with Dan Aykroyd and Daniel Stern were filmed in Charlestown.

- Portions of the 1994 film Blown Away starring Jeff Bridges and Tommy Lee Jones were shot in Charlestown and nearby in Boston Harbor.

- In Matt Damon's Good Will Hunting, the character Dr. Sean Maguire teaches psychology in Charlestown's Bunker Hill Community College.

- Oxy-Morons (2010), an independent film about OxyContin abuse and Johnny Hickey's life in Charlestown.[31]

- The minatory song The Boston Burglar[32] from the 1880s, about a bank robber, contains the lines:

But the jury they found me guilty,

And the judge he wrote it down,

"For breaking of the Union Bank,

You are sent to Charlestown."

From 1805 until 1955 the town was the location of the Charlestown State Prison. Part of the community's association with crime came from families who moved to Charlestown to take advantage of visit programs due to members held there in incarceration

Notable people

- Charles R. Adams (1834–1900), Charlestown native, opera singer[33]

- Charles B. Atwood (1849–1895), born in Charlestown, architect who designed the Reliance Building, among others[33]

- William Austin (1778–1841), born in Charlestown, state legislator and author[33]

- Richard Austin (1598–1638), born in Titchfield, Hampshire, England, and died in Charlestown, Middlesex, Massachusetts; emigrated to 'New England" on the Bevis

- Loammi Baldwin (1780–1838), civil engineer[3]

- Albert Gallatin Blanchard (1810–1891), born in Charlestown, Confederate general in the American Civil War

- Shano Collins (1885–1955), baseball player for Boston Red Sox and for 1917 and 1919 World Series teams of Chicago White Sox

- Thomas Dalton (1794–1883), and his wife Lucy, African American abolitionists and education activists

- Samuel Dexter (1761–1816), prominent lawyer and cabinet member under John Adams

- James Frothingham (1786–1864), portrait artist

- Nathaniel Gorham (1738–1796), a member of the Continental Congress[3]

- John Harvard (1607–1638), English benefactor and namesake of Harvard University

- Robert Haswell (1768–c.1801), maritime trader and officer in the United States Navy during the Quasi-War with France

- Oliver Holden (1765–1831), composer of hymns[3]

- Howie Long, Pro Football Hall of Famer and television commentator

- Samuel F. B. Morse (1791–1872), inventor of the telegraph and Morse code[3]

- Woolson Morse (1858–1897), early Broadway composer

- John Boyle O'Reilly (1844–1890), Irish-born poet, journalist and fiction writer, lived in Charlestown on Winthrop Square

- Alice May Bates Rice (1868–?), opera singer

- Robert Sedgwick (c.1611–1656), English merchant, first major general of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and first governor General of Jamaica[34]

- Matthew Sherman, Mayor of San Diego 1891–1893, born in Charlestown

- Daniel C. Stillson (1830–1899), inventor of the Stillson pipe wrench[35]

- John Hanson Twombly (1814–1893), President of the University of Wisconsin, Methodist minister

See also

References

- ↑ "Boston's Neighborhoods: Charlestown". Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA). 2010. Retrieved August 17, 2010.

- ↑ "Walford Family Line". Retrieved 2009-05-04.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 EB (1911).

- ↑ "A Condensed History of Melrose". Archived from the original on 2009-06-15. City of Melrose. Retrieved 2010-07-15

- ↑ R. H. Howard and Henry E. Crocker, ed. (1880). A History of New England. Volume 1. Boston: Crocker & Co. p. 202.

- ↑ History of the Town of Medford, p. 2

- 1 2 3 EB (1878).

- ↑ Anderson, Rob; Dave Butler; Lauren Frohne; Tom Giratikanon; Monica Ulmanu; Jason Williams; Alan Wirzbicki (2016), "Exploring a New Freedom Trail for the Civil War", Boston Globe

- ↑ "The Charlestown Civil War Memorial", Art Inventories Catalog, Washington: Smithsonian American Art Museum

- ↑ http://www.mwra.state.ma.us/04water/html/hist1.htm

- ↑ "The Result in Figures", The Boston Globe, p. 5, October 8, 1873.

- ↑ "Charlestown District Study #5", Boston City Planning Department, Comprehensive Planning Section, March 14, 1960, p. 1; "Charlestown Preliminary Sketch Plan", Boston Redevelopment Authority, December 15, 1961, p. II-2.

- ↑ Jones, Michael, The Slaughter of Cities: Urban Renewal and Ethnic Cleansing pp. 528–29, St. Augustine's Press, South end Indiana, 2004. ISBN 1-58731-775-3

- ↑ Interactive, Boston. "At a Glance | Boston Redevelopment Authority". bostonredevelopmentauthority.org. Retrieved 2016-04-22.

- ↑ Staff (March 25, 2016). "Housing Developer and Community Working to Make Project Successful". Charlestown Patriot-Bridge. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- 1 2 Barbo, Theresa Mitchell. The Cape Cod Murder of 1899: Edwin Ray Snow's Punishment and Redemption. The History Press, 2007. 29. Retrieved from Google Books on May 23, 2010. ISBN 1-59629-227-X, 9781596292277.

- ↑ "Post Office Location - CHARLESTOWN Archived May 14, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on May 23, 2010.

- ↑ MBTA, Bus 93 Schedule

- ↑ MBTA, Bus 92 Schedule

- ↑ MBTA, Ferry F4 Schedule[Long Wharf (Boston)]

- ↑ Celebrate Boston

- ↑ "Connecticut State Capitol Facts". Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ↑ "Harvard/Kent Elementary School Archived June 12, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.." Boston Public Schools. Retrieved on May 23, 2010.

- ↑ "Clarence R. Edwards Middle School Archived June 12, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.." Boston Public Schools. Retrieved on May 23, 2010.

- ↑ "Warren/Prescott K-8 School." Boston Public Schools. Retrieved on May 23, 2010.

- ↑ "Charlestown High School Archived June 12, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.." Boston Public Schools. Retrieved on May 23, 2010.

- ↑ "Charlestown Branch Library Archived January 5, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.." Boston Public Library. Retrieved on May 23, 2010.

- ↑ "Warren Tavern | A Historic Tavern in Charlestown". www.warrentavern.com. Retrieved 2016-04-15.

- ↑ Boston Globe

- ↑ "Charlestown's Movie Roles". Boston Globe. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ↑ Oxy-Morons at IMDb.com Retrieved 2014-03-27

- ↑ http://www.wtv-zone.com/phyrst/audio/nfld/21/burglar.htm

- 1 2 3 Who Was Who in America, Historical Volume, 1607–1896. Chicago: Marquis Who's Who. 1963.

- ↑ A Sedgwick Genealogy, Descendants of Deacon Benjamin Sedgwick. New Haven: New Haven Colony Historical Society. 1961.

- ↑ Daniel C. Stillson 1830–1899

Bibliography

-

Baynes, T.S., ed. (1878), "Charlestown", Encyclopædia Britannica, 5 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, p. 429

Baynes, T.S., ed. (1878), "Charlestown", Encyclopædia Britannica, 5 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, p. 429 -

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), "Charlestown", Encyclopædia Britannica, 5 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 946

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), "Charlestown", Encyclopædia Britannica, 5 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 946

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charlestown, Boston. |

-

Charlestown travel guide from Wikivoyage

Charlestown travel guide from Wikivoyage - Boston Public Library on Flickr. Photos of Charlestown

- One of the community's web sites, CharlestownOnline.net

- History in pictures and maps

-

"Charlestown. Formerly a city of Middlesex County, Mass., now incorporated with Boston". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

"Charlestown. Formerly a city of Middlesex County, Mass., now incorporated with Boston". New International Encyclopedia. 1905. -

"Charlestown, a city of Middlesex co., Massachusetts". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

"Charlestown, a city of Middlesex co., Massachusetts". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- "Charlestown (Boston, Mass.)". Boston TV News Digital Library. WBGH. 1960s-2000. Check date values in:

|date=(help)