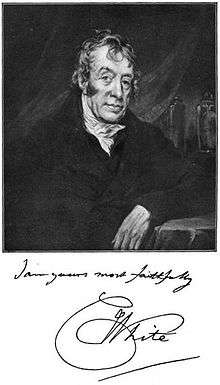

Charles White (physician)

Charles White FRS (4 October 1728 – 20 February 1813) was an English physician and a co-founder of the Manchester Royal Infirmary, along with local industrialist Joseph Bancroft. White was an able and innovative surgeon who made significant contributions in the field of obstetrics.

White kept the mummified body of one of his female patients in a room of his house in Sale for 55 years, probably at least partly because she had a morbid fear of being mistakenly buried alive.

Early life

White was born in Manchester, England, on 4 October 1728, the only son of Thomas White, a surgeon and man-midwife, and his wife Rosamond. After being educated by the Reverend Radcliffe Russell, White joined his father's practice as an apprentice, in about 1742. He subsequently studied medicine in London under the obstetrician William Hunter, before completing his studies in Edinburgh and rejoining his father's practice as a surgeon and man-midwife.[1]

Career

From the 1750s onwards, White became increasingly recognised as an able and innovative surgeon. He presented a paper to the Royal Society in 1760 describing his successful treatment of a fractured arm by reuniting the ends of the broken bone. In 1762, the year he became a fellow of the society, he presented another paper, on the use of sponges to stop bleeding. He became a member of the Company of Surgeons that same year.[1]

White was also highly regarded in the field of obstetrics. His influential book, Treatise on the Management of Pregnant and Lying-in Women, was published in 1773, in which he recommended that women should give birth naturally, and that the delivery should not be assisted until the baby's shoulders had been expelled. He also advised mothers to get out of bed as soon as possible after giving birth, and strongly advocated cleanliness and ventilation.[1]

He defended the controversial theory that "All organisms are arranged in a static chain of being, rising through small gradations from plants to animals to humans".[2] He argued that non-white races were inferior and closer to the primitive due to their skin pigmentation, and that women resembled the darker races because their bodies revealed areas of darker pigmentation: "the areola round the nipple, the pudenda, and the verge of the anus", especially as seen in pregnant women.[3]

Manchester Royal Infirmary

White co-founded the Manchester Royal Infirmary with local industrialist Joseph Bancroft in 1752, and was an honorary surgeon there until 1790,[1] when he was involved in the foundation of St Mary's Hospital, Manchester.[4]

Family and later life

In 1757 White married Ann Bradshaw, whose father had been a high sheriff for the county of Lancaster. They had eight children, four sons and four daughters. In 1803 White suffered an attack of ophthalmia, which led to his blindness a few years later. He died at his home in Sale, on 20 February 1813.[1]

Manchester Mummy

White was the family physician present at the burial of John Beswick, at which a mourner noticed that John's eyelids were flickering, just as his coffin lid was about to be closed; White confirmed that John was still alive. The supposed corpse regained consciousness a few days later, and lived for many more years.[5]

The incident made John's sister, Hannah Beswick, fearful that she might accidentally be buried alive. Following Hannah's death in 1758 White had her embalmed, although it has been suggested that her instructions to him were only that she should be kept above ground until it was obvious that she was dead.[6] White kept Hannah's mummified body in a room in his home in Sale, where it was stored in an old clock case.[7] He had 300 other pathological specimines in his museum.[8] Following his death in 1813, Hannah's mummified body was eventually donated to the Museum of the Manchester Natural History Society,[9] where she became known as the Manchester Mummy, or the Mummy of Birchin Bower.[10] Her body was put on display in the museum's entrance hall,[11] described by one visitor in 1844 as "one of the most remarkable objects in the museum".[12]

Following the museum's transfer to Manchester University in 1867, and with the permission of the Bishop of Manchester, Hannah was buried in an unmarked grave in Harpurhey Cemetery on 22 July 1868.[13]

Polygenism

White concentrated much of his research in the area of polygenism, in which he became a very strong believer.[14] He followed the conception of race introduced by Lord Kames.[15] Today, his views appear to be scientific racism.

White's Account of the Regular Gradation in Man, and in Different Animals and Vegetables[16] (1799) provided the empirical science for polygenism. White defended the theory of polygeny by refuting French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon's interfertility argument – the theory that only the same species can interbreed – pointing to species hybrids such as foxes, wolves and jackals, separate groups that were still able to interbreed. For White each race was a separate species, divinely created for its own geographical region.[15] Not only did White talk about species dealing with animals, he also discussed his views on the diversity of human species. He concentrated heavily on Africans and African Americans and their distinct differences from Europeans, which later led him to believe they derived from a separate origin, specifically primates.[14]

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 Butler, Stella (2004), "White, Charles (1728–1813)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.), Oxford University Press, retrieved 6 February 2009 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ↑ White (1799), pp. 134–135

- ↑ Meyer (1996), p. 16

- ↑ Brockbank, William (1952). Portrait of a Hospital. London: William Heinemann. p. 32.

- ↑ Hyde, O'Rourke & Portland (2004), p. 43

- ↑ Dobson, Jessie (1953), "Some Eighteenth Century Experiments in Embalming", Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, Oxford University Press, 8 (4): 431–441, ISSN 0022-5045, PMID 13109185, doi:10.1093/jhmas/VIII.October.431

- ↑ Bondeson (2001), p. 87

- ↑ Leach, Penny (1990). St Mary's Hospital Manchester 1790-1990. Manchester.

- ↑ Portland (2002), p. 85

- ↑ Cooper (2007), p. 87

- ↑ Bondeson (1997), p. 102

- ↑ Kohl (1844), p. 130

- ↑ Portland 2002, pp. 82–83.

- 1 2 White, Charles (1779), "Charles White, Regular Gradation in Man, and in Different Animals and Vegetables" (PDF), Philosophical Society of Manchester, retrieved 11 October 2014

- 1 2 Jackson & Weidman (2004), pp. 39–41

- ↑ White (2013), p. 201.

Bibliography

- Bondeson, Jan (1997), A Cabinet of Medical Curiosities, I. B. Tauris, ISBN 978-1-86064-228-9

- Bondeson, Jan (2001), Buried Alive: the terrifying history of our most primal fear, W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 978-0-393-04906-0

- Cooper, Glynis (2007), Manchester's Suburbs, The Breedon Books Publishing Company, ISBN 978-1-85983-592-0

- Hyde, Matthew; O'Rourke, Aidan; Portland, Peter (2004), Around the M60: Manchester's orbital motorway, AMCD (Publishers), ISBN 978-1-897762-30-1

- Jackson, John P.; Weidman, Nadine M. (2004), Race, Racism, And Science: Social Impact And Interaction, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-85109-448-6

- Kohl, Johann Georg (1844), England, Wales and Scotland, Chapman and Hall

- Meyer, Susan (1996), Imperialism at Home: Race and Victorian women's fiction, Cornell University Press, ISBN 978-0-8014-8255-7

- Portland, Peter (2002), Around Haunted Manchester, AMCD (Publishers), ISBN 978-1-897762-25-7

- White, Charles (1799), An Account of the Regular Gradation in Man, and in different Animals and Vegetables, C. Dilly

- White, Deborah (2013), Freedom on My Mind, A History of African Americans, Bedford /St. Martin, ISBN 978-0-312-19729-2

Further reading

- Cullingworth, Charles (1904), Charles White, F. R. S., Henry J. Glaisher