Charles Stark Draper Laboratory

|

| |

| Independent, not-for-profit corporation | |

| Industry |

Defense Space Biomedical Energy |

| Founded |

1932 as the MIT Confidential Instrument Development Laboratory[1] 1973 became The Charles Stark Draper Laboratory, Inc. |

| Headquarters | 555 Technology Square, Cambridge, MA 02139-3563 |

Number of locations | 6 |

Key people | Dr. Kaigham (Ken) J. Gabriel, President and CEO (2014-) [2] |

| Revenue | $493 million (Fiscal Year 2010) [3] |

Number of employees | 1,400[3][4] |

| Website | draper.com |

Draper is an American not-for-profit research and development organization, headquartered in Cambridge, Massachusetts; its official name is "The Charles Stark Draper Laboratory, Inc".[5] The laboratory specializes in the design, development, and deployment of advanced technology solutions to problems in national security, space exploration, health care and energy.

The laboratory was founded in 1932 by Charles Stark Draper at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to develop aeronautical instrumentation, and came to be called the "MIT Instrumentation Laboratory".[6] It was renamed for its founder in 1970 and separated from MIT in 1973 to become an independent, non-profit organization.[1][6][7]

The expertise of the laboratory staff includes the areas of guidance, navigation, and control technologies and systems; fault-tolerant computing; advanced algorithms and software solutions; modeling and simulation; and microelectromechanical systems and multichip module technology.

History

In 1932 Charles Stark Draper, an MIT aeronautics professor, created a teaching laboratory to develop the instrumentation needed for tracking, controlling and navigating aircraft. During World War II, Draper’s lab was known as the “Confidential Instrument Development Laboratory”. Later, the name was changed to the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory. The laboratory was renamed for its founder in 1970 and remained a part of MIT until 1973 when it became an independent, not-for-profit research and development corporation.[1][6][8] The transition to an independent corporation arose out of pressures for divestment of MIT laboratories doing military research at the time of the Vietnam War, despite the absence of a role of the laboratory in that war.[9]

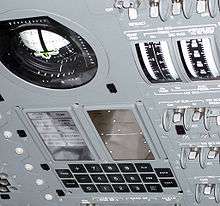

A primary focus of the laboratory's programs throughout its history has been the development and early application of advanced guidance, navigation, and control (GN&C) technologies to meet the U.S. Department of Defense’s and NASA’s needs. The laboratory’s achievements includes the design and development of accurate and reliable guidance systems for undersea-launched ballistic missiles as well as the Apollo Guidance Computer that guided the Apollo astronauts to the Moon and back safely to Earth, every time. The laboratory contributed to the development of inertial sensors, software, and other systems for the GN&C of commercial and military aircraft, submarines, strategic and tactical missiles, spacecraft, and unmanned vehicles.[10]

Inertial-based GN&C systems were central for navigating ballistic missile submarines for long periods of time undersea to avoid detection and guiding their submarine-launched ballistic missiles to their targets, starting with the UGM-27 Polaris missile program.

Locations

Draper has locations in several U.S. cities:[3]

- Cambridge, MA (headquarters)

- Houston, TX at NASA Johnson Space Center

- Washington, DC

- Huntsville, AL

Former Locations

- Tampa, FL at University of South Florida (Bioengineering Center)

- St. Petersburg, FL (Multichip Module Facility)

Technical areas

According to its website,[3] the laboratory staff applies its expertise to autonomous air, land, sea and space systems; information integration; distributed sensors and networks; precision-guided munitions; biomedical engineering; chemical/biological defense; and energy system modeling and management. When appropriate, Draper works with partners to transition their technology to commercial production.

The laboratory encompasses seven areas of technical expertise:

- Strategic Systems—Application of guidance, navigation, and control (GN&C) expertise to hybrid GPS-aided technologies and to submarine navigation and strategic weapons security.

- Space Systems—As "NASA’s technology development partner and transition agent for planetary exploration", development of GN&C and high-performance science instruments. Expertise also addresses the national security space sector.

- Tactical Systems—Development of: maritime intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) platforms, miniaturized munitions guidance, guided aerial delivery systems for materiel, soldier-centered physical and decision support systems, secure electronics and communications, and early intercept guidance for missile defense engagement.

- Special Programs—Concept development, prototyping, low-rate production, and field support for first-of-a-kind systems, connected with the other technical areas.

- Biomedical Systems—Microelectromechanical systems (MEMS), microfluidic applications of medical technology, and miniaturized smart medical devices.

- Air Warfare and ISR—Intelligence technology for targeting and target planning applications.

- Energy Solutions—Managing the reliability, efficiency, and performance of equipment throughout complex energy generation and consumption systems, including coal-fired power plants or the International Space Station.

Project areas in the news

.jpg)

Project areas that have surfaced in the news referred to Draper Laboratory's core expertise in inertial navigation, as recently as 2003. More recently, emphasis has shifted to research in innovative space navigation topics, intelligent systems that rely on sensors and computers to make autonomous decisions, and nano-scale medical devices.

Inertial navigation

The laboratory staff has studied ways to integrate input from Global Positioning Systems (GPS) into Inertial navigation system-based navigation in order to lower costs and improve reliability. Military inertial navigation systems (INS) cannot totally rely on GPS satellite availability for course correction—required by error growth—owing to blocking or jamming of signal. A less accurate inertial system usually means a less costly system, but one that requires more frequent checking of position from another source, like GPS. Systems that integrate GPS with INS are classified as “loosely coupled” (pre-1995), “tightly coupled” (1996-2002), or "deeply integrated" (2002 onwards), depending on the degree of integration of the hardware.[11] As of 2006, it was envisioned that many military and civilian uses would integrate GPS with INS, including the possibility of shells with a deeply integrated system that can withstand 20,000 g, when fired from an artillery piece.[12]

Space navigation

In 2010 Draper Laboratory and MIT collaborated with two other partners as part of the Next Giant Leap team to win a grant towards achieving the Google Lunar X Prize send the first privately funded robot to the Moon. To qualify for the prize, the robot must travel 500 meters across the lunar surface and transmit video, images and other data back to Earth. A team developed a "Terrestrial Artificial Lunar and Reduced Gravity Simulator" to simulate operations in the space environment, using Draper Laboratory's guidance, navigation and control algorithm for reduced gravity.[13][14]

In 2012, Draper laboratory engineers in Houston, Texas developed a new method for turning NASA's International Space Station, called the “optimal propellant maneuver”, which achieved a 94 percent savings over previous practice. The algorithm takes into account everything that affects how the station moves, including "the position of its thrusters and the effects of gravity and gyroscopic torque".[15]

At a personal scale Draper, as of 2013, was developing a garment for use in orbit that uses Controlled Moment Gyros (CMGs) that creates resistance to movement of an astronaut's limbs to help mitigate bone loss and maintain muscle tone during prolonged space flight. The unit is called a Variable Vector Countermeasure suit, or V2Suit, which uses CMGs also to assist in balance and movement coordination by creating resistance to movement and an artificial sense of "down". Each CMG module is about the size of a deck of cards. The concept is for the garment to be worn "in the lead-up to landing back on Earth or periodically throughout a long mission."[16]

In 2013, a Draper/MIT/NASA team was also developing a CMG-augmented space suit that would expand the current capabilities of NASA's "Simplified Aid for EVA Rescue" (SAFER)—a space suit designed for "propulsive self-rescue" for when an astronaut accidentally becomes untethered from a spacecraft. The CMG-augmented suit would provide better counterforce than is now available for when astronauts use tools in low-gravity environments. Counterforce is available on earth from gravity. Without it an applied force would result in an equal force in the opposite direction, either in a straight line or spinning. In space this could send an astronaut out of control. Currently, astronauts must affix themselves to the surface being worked on. The CMGs would offer an alternative to mechanical connection or gravitational force.[17]

Intelligent systems

Draper researchers develop artificial intelligence systems to allow robotic devices to learn from their mistakes, This work is in support of DARPA-funded work, pertaining to the Army Future Combat System. This capability would allow an autonomous under fire to learn that that road is dangerous and find a safer route or to recognize that its fuel status and damage status. Paul DeBitetto, reportedly led the cognitive robotics group at the laboratory in this effort, as of 2008.[18]

As of 2009, the US Department of Homeland Security funded Draper Laboratory and other collaborators to develop a technology to detect potential terrorists with cameras and other sensors that monitor behaviors of people being screened. The project is called “Future Attribute Screening Technology’’ or FAST. The application would be for security checkpoints to assess candidates for follow-up screening. In a demonstration of the technology, the project manager Robert P. Burns explained that the system is designed to distinguish between malicious intent and benign expressions of distress by employing a substantial body research into the psychology of deception.[19]

As of 2010 Neil Adams, a director of tactical systems programs for Draper Laboratory, led the systems integration of Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency's (DARPA) Nano Aerial Vehicle (NAV) program to miniaturize flying reconnaissance platforms. This entails managing the vehicle, communications and ground control systems allow NAVs to function autonomously to carry a sensor payload to achieve the intended mission. The NAVS must work in urban areas with little or no GPS signal availability, relying on vision-based sensors and systems.[20]

Medical systems

In 2009, Draper collaborated with the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary to develop an implantable drug-delivery device, which "merges aspects of microelectromechanical systems, or MEMS, with microfluidics, which enables the precise control of fluids on very small scales." The device is a "flexible, fluid-filled machine", which uses tubes that expand and contract to promote fluid flow through channels with a defined rhythm, driven by a micro-scale pump, which adapts to environmental input. The system, funded by the National Institutes of Health, may treat hearing loss by delivering "tiny amounts of a liquid drug to a very delicate region of the ear, the implant will allow sensory cells to regrow, ultimately restoring the patient's hearing".[21]

As of 2010, Heather Clark of Draper Laboratory was developing a method to measure blood glucose concentration without finger-pricking. The method uses a nano-sensor, like a miniature tattoo, just several millimeters across, that patients applies to the skin. The sensor uses near-infrared or visible light ranges to determine glucose concentrations. Normally to regulate their blood glucose levels, diabetics must measure their blood glucose at several times a day by taking a drop of blood obtained by a pinprick and inserting the sample into a machine that can measure glucose level. The nano-sensor approach would supplant this process.[22]

Notable innovations

Laboratory staff worked in teams to create novel navigation systems, based on inertial guidance and on digital computers to support the necessary calculations for determining spatial positioning.

- Mark 14 Gunsight (1942)—Improved gunsight accuracy of anti-aircraft guns used aboard naval vessels in WWII[23]

- Space Inertial Reference Equipment (SPIRE) (1953)—An autonomous all-inertial navigation for aircraft whose feasibility the laboratory demonstrated in a series of 1953 flight tests.[12][24]

- The Laning and Zierler system (1954: also called, "George")—An early algebraic compiler, designed by J. Halcombe Laning and Neal Zierler.[25]

- Q-guidance—A method of missile guidance, developed by J. Halcombe Laning and Richard Battin[26]

- Apollo Guidance Computer—The first deployed computer to exploit integrated circuit technology of on board, autonomous navigation in space[27]

- Digital Fly-by-wire—A control system that allowed a pilot to control the aircraft without being connected mechanically to the aircraft’s control surfaces[28]

- Fault-tolerant Computing—Use of several computers work on a task simultaneously. If any one of the computers fails, the others can take over a vital capability when the safety of an aircraft or other system is at stake.[29]

- Micro-electromechanical (MEMS) technologies—Micro-mechanical systems that enabled the first micromachined gyroscope.[30]

- Autonomous systems algorithms—Algorithms, which allow autonomous rendezvous and docking of spacecraft; systems for underwater vehicles

- GPS coupled with inertial navigation system—A means to allow continuous navigation when the vehicle or system goes into a GPS-denied environment[11]

Outreach programs

Draper Laboratory applies some of its resources to developing and recognizing technical talent through educational programs and accomplishments through the Draper Prize.

Technical education

The research-based Draper Fellow Program sponsors about 50 graduate students each year.[31] Students are trained to fill leadership positions in the government, military, industry, and education. The laboratory also supports on-campus funded research with faculty and principal investigators through the University R&D program. It offers undergraduate student employment and internship opportunities.

Draper Laboratory conducts a STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) K-12 and community education outreach program, which it established in 1984.[32] Each year, laboratory distributes more than $175,000 through its community relations programs.[33] These funds include support of internships, co-ops, participation in science festivals and the provision of tours and speakers-is an extension of this mission.[34]

Draper Prize

The company endows the Charles Stark Draper Prize, which is administered by the National Academy of Engineering. It is awarded "to recognize innovative engineering achievements and their reduction to practice in ways that have led to important benefits and significant improvement in the well-being and freedom of humanity." Achievements in any engineering discipline are eligible for the $500,000 prize.[35]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Editors. "The Charles Stark Draper Laboratory, Inc.—History". Funding Universe. Retrieved 2013-12-28.

- ↑ "Ken Gabriel, former DARPA, Google Executive, to Lead Draper Laboratory" (Press release). Cambridge, MA: The Charles Stark Draper Laboratory, Inc. 21 July 2014. Archived from the original on 20 May 2014. Retrieved 2015-08-04.

- 1 2 3 4 Editors. "Profile: Draper". Website. The Charles Stark Draper Laboratory, Inc. Archived from the original on 2011-06-12. Retrieved 2013-12-28.

- ↑ Levy, Mark (10 October 2009). "The top 10 employers in Cambridge—and how to contact them". Cambridge Day.

- ↑ "Founding Consortium Institution: The Charles Stark Draper Laboratory, Inc.". Center for Integration of Medicine and Innovative Technology (CIMIT).

- 1 2 3 Morgan, Christopher; O’Connor, Joseph; Hoag, David (1998). "Draper at 25—Innovation for the 21st Century" (PDF). The Charles Stark Draper Laboratory, Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-01. Retrieved 2013-12-28.

- ↑ "Draper Laboratory". MIT Course Catalog 2013-2014. MIT.

- ↑ Editors. "History". Website. The Charles Stark Draper Laboratory, Inc. Retrieved 2013-12-28.

- ↑ Leslie, Stuart W. (2010). Kaiser, David, ed. Becoming MIT: Moments of Decision. MIT Press. pp. 124–137. ISBN 978-0-262-11323-6.

- 1 2 Schmidt, G.; Phillips, R. (October 2003). "INS/GPS Integration Architectures" (PDF). NATO RTO Lecture. NATO. Advances in Navigation Sensors and Integration Technology (232): 5–1–5–15. Retrieved 2013-12-28.

- 1 2 Schmidt, George T. "INS/GPS Technology Trends" (PDF). NATO R&T Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-24. Retrieved 2013-12-23.

- ↑ Klamper, Amy (13 April 2011). "Draper, MIT Students Test Lunar Hopper with Eyes on Prize". Space News. Retrieved 2013-12-24.

- ↑ Wall, Mike (27 January 2011). "Coming Soon: Hopping Moon Robots for Private Lunar Landing". Space.com. Retrieved 2013-12-24.

- ↑ Bleicher, Ariel (2 August 2012). "NASA Saves Big on Fuel in ISS Rotation". IEEE Spectrum. Retrieved 2013-12-23.

- ↑ Kolawole, Emi (1 June 2013). "When you think gyroscopes, go ahead and think the future of spacesuits and jet packs, too". Washington Post. Retrieved 2013-12-25.

- ↑ Garber, Megan (30 May 2013). "The Future of the Spacesuit—It involves gyroscopes. And better jetpacks.". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2013-12-25.

- ↑ Jean, Grace V. (March 2008). "Robots Get Smarter, But Who Will Buy Them?". National Defense. National Defense Industrial Association. Retrieved 2013-12-23.

- ↑ Johnson, Carolyn Y. (September 18, 2009). "Spotting a terrorist—Next-generation system for detecting suspects in public settings holds promise, sparks privacy concerns". Boston Globe. Retrieved 2013-12-24.

- ↑ Smith, Ned (1 July 2010). "Military Plans Hummingbird-Sized Spies in the Sky". Tech News Daily. Retrieved 2013-12-24.

- ↑ Borenstein, Jeffrey T. (30 Oct 2009). "Flexible Microsystems Deliver Drugs Through the Ear—A MEMS-based microfluidic implant could open up many difficult-to-treat diseases to drug therapy". IEEE Spectrum. Retrieved 2013-12-23.

- ↑ Kranz, Rebecca; Gwosdow, Andrea (September 2009). "Honey I Shrunk the…Sensor?". What a Year. Massachusetts Society for Medical Research. Retrieved 2013-12-24.

- ↑ "U.S. Navy Mark 14 Gunsight, MIT Instrumentation Laboratory, 1940s." MIT Museum. Retrieved 2011-08-16.

- ↑ Gruntman, Mike (2004). Blazing the Trail: The Early History of Spacecraft and Rocketry. AIAA. p. 204.

- ↑ Battin, Richard H. (1995-06-07). "On algebraic compilers and planetary fly-by orbits". Acta Astronautica. Jerusalem. 38 (12): 895–902. doi:10.1016/s0094-5765(96)00095-1.

- ↑ Spinardi, Graham (1994). From Polaris to Trident: The Development of US Fleet Ballistic Missile. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 44–45.

- ↑ Hall, Eldon C. (1996). Journey to the Moon: The History of the Apollo Guidance Computer. AIAA.

- ↑ Editors (15 April 2010). "Draper, Digital Fly-by-Wire Team Enters Space Hall of Fame". Space Foundation. Retrieved 2013-12-28.

- ↑ Rennels, David A. (1999). "Fault-Tolerant Computing" (PDF). Encyclopedia of Computer Science. UCLA. Retrieved 2013-12-28.

- ↑ Sarvestani, Arezu (8 June 2011). "Draper's tiny bio-MEM tech goes from a head-scratcher to a no-brainer". Mass Device. Massachusetts Medical Devices Journal. Retrieved 2013-12-28.

- ↑ Donnelly, Julie M. (4 January 2011). "Draper program prepares fellows for advanced, niche roles". Mass High Tech. Boston Business Journal. Retrieved 2013-12-28.

- ↑ Mytko, Denise. "Educational Outreach". Website. The Charles Stark Draper Laboratory, Inc. Archived from the original on 2011-06-12. Retrieved 2013-12-28.

- ↑ Editors (23 November 2010). "2010 Tech Citizenship honoree: Charles Stark Draper Laboratory Inc.". Mass High Tech. Boston Business Journal. Retrieved 2013-12-28.

- ↑ Mytko, Denise. "Community Relations". Website. The Charles Stark Draper Laboratory, Inc. Archived from the original on 2011-06-12. Retrieved 2013-12-28.

- ↑ Editors (26 September 2013). "Charles Stark Draper Prize for Engineering". Website. National Academy of Engineering. Retrieved 2013-12-28.