Charles Lydiard

| Charles Lydiard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | fl. 13 May 1780 |

| Died |

29 December 1807 Aboard HMS Anson, Mounts Bay, Cornwall |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1780–1807 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Commands held |

HMS Utile HMS Fury HMS Kite HMS Anson |

| Battles/wars |

|

Charles Lydiard (fl. 13 May 1780 – 29 December 1807) was an officer of the Royal Navy who served during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

Lydiard's origins are obscure, but he joined the navy in 1780 and rose through the ranks after distinguished service in the early years of the French Revolutionary Wars, particularly during the Siege of Toulon. He saw action in several engagements in the Mediterranean, and had a part in the defeat of a French frigate in 1795. The chance for promotion passed him by however when the French ship escaped. He again demonstrated his qualities on a cutting-out expedition under the guns of a French shore battery, and this time was successful in escaping with his prize. He was promoted and appointed to the command of his prize, and went on to be captain of several small vessels before a period of unemployment caused by his promotion to post-captain. He returned to active service in 1805 with command of the razee HMS Anson, in which ship he distinguished himself in a number of incidents in the West Indies, capturing a Spanish frigate, attacking a French ship of the line, and helping to capture the island of Curaçao. He returned to Britain after these exploits, but his ship was caught in a gale, and despite his best efforts, was driven ashore and wrecked. Lydiard did his utmost to save as many of his men as he could, before being swept away and drowned.

Early life

Lydiard's origins are largely unknown, but his entry to the navy is recorded as being on 13 May 1780, when he joined the 100-gun HMS Britannia as a captain's servant.[1] The Britannia was at this time the flagship of Vice-Admiral George Darby, commander of the Channel Fleet.[2] Lydiard was appointed an able seaman on 25 July 1781, and on 27 May 1782 was transferred to the 44-gun HMS Resistance, at first as an able seaman, but receiving a promotion to midshipman on 12 October that year.[1] He went on to serve aboard the 74-gun HMS Bombay Castle and HMS Edgar, and passed his lieutenant's examination on 27 May 1791.[1] He was serving with Lord Hood's fleet during the occupation of Toulon in the early months of the French Revolutionary Wars. Lydiard distinguished himself with his actions during the hard-fought defence of Fort Mulgrave, and received his commission on 25 November 1793.[1]

Lieutenancy

He then became first lieutenant of HMS Sincere, one of the prizes from Toulon, under the command of Commander William Shield. Shield and Lydiard served along the French Mediterranean coast until October 1794, and were engaged in cutting-out enemy ships from French harbours.[3] Sincere was then paid off and Lydiard transferred to the 74-gun HMS Captain, where he saw action at the Battle of Genoa on 14 March and the Battle of Hyères Islands on 13 July 1795.[3] His former commander, William Shield, had received command of the 32-gun HMS Southampton by July 1795, and Lydiard transferred that month to serve as his first lieutenant.[1][3] Lydiard remained with Southampton after Shield's replacement by Captain James Macnamara and in September 1795 they spent 15 days blockading a French grain convoy in the port of Genoa.

Southampton and the French

The convoy was protected by two frigates, the Vestale and the Brun.[4] The French finally came out on the evening of the fifteenth day, and were engaged by Southampton, despite the French possessing considerably more firepower.[4] After a sustained engagement Southampton forced Vestale to strike her colours while the Brun escaped with the convoy, leaving Vestale to her fate.[4] But as Southampton prepared to lower her boats to take possession of the French ship, her fore-mast, which had been damaged during the engagement, went by the board.[4] Taking advantage of this, Vestale raised her colours and escaped from the scene.[4] Victory over the Vestale should have brought promotions for Southampton's officers, including Lydiard, but her escape deprived them of this. Lydiard now had to secure another triumph to ensure his promotion.[1]

Capture of Utile

Lydiard's next opportunity to distinguish himself came in June 1796. On 9 June a French corvette was sighted entering Hyères bay, and Vice-Admiral Sir John Jervis, commander of the Mediterranean Fleet, summoned Macnamara to his flagship, HMS Victory.[4] He asked Macnamara to bring out the French ship if he could. Recognising the difficulty and risk that would be involved, he did not make it a formal written order, instead instructing Macnamara 'bring out the enemy's ship if you can; I'll give you no written order; but I direct you to take care of the king's ship under your command.'[5] Macnamara promptly took his ship in under the guns of the batteries, and apparently having been mistaken for a French or neutral frigate, closed to within pistol shot of the French ship, and demanded her captain surrender.[5] The captain replied with a broadside, and Macnamara brought Southampton alongside and sent Lydiard over in command of the boarders. After subduing fierce resistance Lydiard took possession of the French ship and together he and Macnamara escaped out to sea under heavy fire from the French shore batteries.[5] Macnamara wrote in a letter to Jervis

At this period, being very near the heavy battery of Fort Breganson, I laid him instantly onboard, and Lieutenant Lydiard, at the head of the boarders, with an intrepidity that no words can describe entered and carried her in about ten minutes, although he met with a spirited resistance from the captain (who fell) and a hundred men under arms to receive him. In this short conflict, the behaviour of all the officers and ship's company of the Southampton had my full approbation, and I do not mean to take from their merit by stating to you, that the conduct of Lieutenant Lydiard was above all praise.— J. Macnamara, [5]

The prize, a 24-gun corvette named Utile, was taken into service with the Royal Navy as HMS Utile and Lydiard was promoted and given command of her, a commission confirmed on 22 July 1796.[1][6]

Command

Lydiard spent some time in the Adriatic before returning to Britain in 1797 as a convoy escort, after which Utile was paid off.[7] He was appointed to command the bomb vessel HMS Fury in May 1798, followed by the sloop HMS Kite in November that year.[8][9] He served aboard Kite in the North Sea until his promotion to post-captain on 1 January 1801, at which point he was superseded in the command of the Kite.[7] No further commands could be found for him, and the Peace of Amiens further lengthened his enforced retirement from active service.[1][7] He went ashore during this time, and took the opportunity to marry.[1] The couple had three sons together.[1]

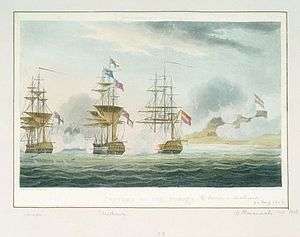

Lydiard finally returned to active service in December 1805, with an appointment to command the 38-gun HMS Anson.[1][10] Anson had originally been a 64-gun third rate, but had been razeed in 1794.[11] He sailed Anson to the West Indies in early 1806 and in August was sailing in company with Captain Charles Brisbane's HMS Arethusa when on 23 August they came across the 38-gun Spanish frigate Pomona off Havana, guarded by a shore battery and twelve gunboats.[7] The Pomona was trying to enter the harbour, whereupon Lydiard and Brisbane bore up and engaged her.[12] The gunboats came out to defend her, whereupon the two British frigates anchored between the shore battery and gunboats on one side, and the Pomona on the other. A hard fought action began, which lasted for 35 minutes until the Pomona struck her colours.[12] Three of the gunboats were blown up, six were sunk, and the remaining three were badly damaged.[13] The shore battery was obliged to stop firing after an explosion in one part of it.[12] There were no casualties aboard Anson, but Arethusa lost two killed and 32 wounded, with Brisbane among the latter.[12] The captured Pomona was subsequently taken into the Navy as HMS Cuba.[14][15]

Anson and Foudroyant

Lydiard remained cruising off Havana, and on 15 September sighted the French 84-gun Foudroyant.[16] The Foudroyant, carrying the flag of Vice-Admiral Jean-Baptiste Willaumez, had been dismasted in a storm and was carrying a jury-rig. Despite the superiority of his opponent and the nearness of the shore Lydiard attempted to close on the French vessel and opened fire.[16] Anson came under fire from the fortifications at Morro Castle, while several Spanish ships, including the 74-gun San Lorenzo, came out of Havana to assist the French.[17] After being unable to manoeuvre into a favourable position and coming under heavy fire, Lydiard hauled away and made his escape.[17] Anson had two killed and 13 wounded during the engagement, while the rigging was badly cut. Foudroyant meanwhile had 27 killed or wounded.[17]

Capture of Curaçao

Anson was then assigned to Charles Brisbane's squadron and joined Brisbane's Arethusa and James Athol Wood's HMS Latona. The ships were despatched in November 1806 by Vice-Admiral James Richard Dacres to reconnoitre Curaçao.[13][18] They were joined in December by HMS Fisgard and Brisbane decided to launch an attack on 1 January 1807.[18] The British ships approached early in the morning of 1 January and anchored in the harbour.[18] They were attacked by the Dutch, at which Brisbane boarded and captured the 36-gun frigate Halstaar, while Lydiard attacked and secured the 20-gun corvette Suriname.[19] Both Lydiard and Brisbane then led their forces on shore, and stormed Fort Amsterdam, which was defended by 270 Dutch troops.[19] The fort was carried after ten minutes of fighting, after which two smaller forts, a citadel and the entire town were also taken.[19] More troops were landed while the ships sailed round the harbour to attack Fort République. By 10 am the fort had surrendered, and by noon the entire island had capitulated.[19] Lydiard was sent back to Britain carrying the despatches and captured colours.[20] The dramatic success of the small British force carrying the heavily defended island was rewarded handsomely. Brisbane was knighted, and the captains received swords, medals and vases.[21]

Wreck of Anson

Anson was sent back to Britain shortly afterwards, and Lydiard rejoined his ship at Plymouth.[13] After a period refitting Anson was assigned to the Channel Fleet and ordered to support the blockade of Brest by patrolling off Black Rocks.[13] She sailed from Falmouth on 24 December, and reached Ile de Bas on 28 December. With a gale blowing up from the south west, Lydiard decided to return to port.[22] He made for the Lizard, but in the poor weather, came up on the wrong side and became trapped on a lee shore, with breakers ahead.[22] Anson rolled heavily in rough seas, having retained the spars from her days as a 64-gun ship after she had been razeed.[13] Lydiard's only option was to anchor, but early on the morning of 29 December the rising storm caused the anchor cables to part and she was driven onto the shore.[23] Lydiard ordered the ship to be run onto a beach in the hope of saving as many lives as possible, and resolved to remain aboard to oversee the evacuation.[13][24] The pounding surf prevented boats from being launched from the ship or the shore, and a number of the crew were swept away. Some managed to clamber along the fallen main-mast to the shore, while Lydiard clung to the wheel to encourage them on.[24][25] Eyewitnesses recorded that Lydiard had exhausted himself with the effort of organising the evacuation and clinging to the wreck in the violence of the storm.[25] He attempted to leave the ship, but became distracted by trying to help a boy. In doing so Lydiard was washed away and drowned.[25] The Naval Chronicle's account of the wreck recorded that

It was the captain's great wish to save the lives of the ship's company, and he was employed in directing them the whole of the time. He had placed himself by the wheel, holding the spokes, where he was exposed to the violence of the sea, which broke tremendously over him, and from continuing in this situation too long, wishing to see the people out of the ship, he became so weak, that, upon attempting to leave the ship himself, and being impeded by a boy who was in his way, and whom he endeavoured to assist, he was washed away and drowned.— The Naval Chronicle, volume 19, 1808, p. 453

A total of sixty of Anson's crew were lost, including her captain and her first-lieutenant. Lydiard's body was recovered and a funeral service was held at Falmouth, attended by Admiral Sir Charles Cotton and large numbers of army and navy officers, as well as the local dignitaries.[13][26] The body was later interred in the family vault at Haslemere, Surrey.[26]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Tracy. Who's who in Nelson's Navy. p. 231.

- ↑ Campbell. The naval history of Great Britain. p. 188.

- 1 2 3 Campbell. The naval history of Great Britain. p. 189.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Campbell. The naval history of Great Britain. p. 190.

- 1 2 3 4 Campbell. The naval history of Great Britain. p. 191.

- ↑ Winfield. British Warships of the Age of Sail 1794–1817. p. 214.

- 1 2 3 4 Campbell. The naval history of Great Britain. p. 192.

- ↑ Winfield. British Warships of the Age of Sail 1794–1817. p. 231.

- ↑ Winfield. British Warships of the Age of Sail 1794–1817. p. 263.

- ↑ Winfield. British Warships of the Age of Sail 1794–1817. p. 92.

- ↑ Gardiner. Frigates of the Napoleonic Wars. p. 41.

- 1 2 3 4 James. James' Naval History. p. 317.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Tracy. Who's who in Nelson's Navy. p. 232.

- ↑ Colledge. Ships of the Royal Navy. p. 85.

- ↑ Winfield. British Warships of the Age of Sail 1794–1817. p. 202.

- 1 2 Campbell. The naval history of Great Britain. p. 193.

- 1 2 3 Campbell. The naval history of Great Britain. p. 194.

- 1 2 3 Allen. Battles of the British Navy. p. 186.

- 1 2 3 4 Allen. Battles of the British Navy. p. 187.

- ↑ Campbell. The naval history of Great Britain. p. 198.

- ↑ Allen. Battles of the British Navy. p. 188.

- 1 2 Gilly. Narratives of Shipwrecks of the Royal Navy. p. 126.

- ↑ Gilly. Narratives of Shipwrecks of the Royal Navy. p. 127.

- 1 2 Campbell. The naval history of Great Britain. p. 201.

- 1 2 3 Gilly. Narratives of Shipwrecks of the Royal Navy. p. 128.

- 1 2 Campbell. The naval history of Great Britain. p. 202.

References

- Allen, Joseph (1852). Battles of the British Navy. 2. Henry G. Bohn.

- Campbell, John; Stockdale, John Joseph (1818). The naval history of Great Britain: commencing with the earliest period of history, and continued to the expedition against Algiers, under the command of Lord Exmouth, in 1816. Including the history and lives of British admirals. 8. Baldwyn and co.

- Clarke, James Stanier; Jones, Stephen (1808). The Naval Chronicle. 18. J. Gold.

- Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Rev. ed.). London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8. OCLC 67375475.

- Gardiner, Robert (2006). Frigates of the Napoleonic Wars. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-292-5.

- Gilly, William Stephen; Gilly, William Octavius Shakespeare (1851). Narratives of shipwrecks of the Royal Navy: between 1793 and 1849. J. W. Parker.

- James, William. James' Naval History. Epitomised in one volume by Robert O'Byrne. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 1-4021-8133-7.

- Tracy, Nicholas (2006). Who's who in Nelson's Navy: 200 Naval Heroes. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-244-5.

- Winfield, Rif (2007). British Warships of the Age of Sail 1794–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth. ISBN 1-86176-246-1.