Charles Holden

| Charles Henry Holden | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Charles Holden by Benjamin Nelson, 1910 | |

| Born |

12 May 1875 Great Lever, Bolton, Lancashire, England, UK |

| Died |

1 May 1960 (aged 84) Harmer Green, Hertfordshire, England, UK |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Awards |

RIBA London Architecture Medal for 1929 (awarded 1931) RIBA Royal Gold Medal (1936) Royal Designer for Industry (1943) |

| Buildings |

55 Broadway Senate House Bristol Central Library London Underground stations Cemeteries for Imperial War Graves Commission |

Charles Henry Holden Litt.D, FRIBA, MRTPI, RDI (12 May 1875 – 1 May 1960) was a Bolton-born English architect best known for designing many London Underground stations during the 1920s and 1930s, for Bristol Central Library, the Underground Electric Railways Company of London's headquarters at 55 Broadway and for the University of London's Senate House. He also created many war cemeteries in Belgium and northern France for the Imperial War Graves Commission.

After working and training in Bolton and Manchester, Holden moved to London. His early buildings were influenced by the Arts and Crafts Movement, but for most of his career he championed an unadorned style based on simplified forms and massing that was free of what he considered to be unnecessary decorative detailing.[note 1] Holden believed strongly that architectural designs should be dictated by buildings' intended functions. After the First World War he increasingly simplified his style and his designs became pared-down and modernist, influenced by European architecture. He was a member of the Design and Industries Association and the Art Workers' Guild. He produced complete designs for his buildings including the interior design and architectural fittings.

Although not without its critics, his architecture is widely appreciated. He was awarded the Royal Institute of British Architects' (RIBA's) Royal Gold Medal for architecture in 1936 and was appointed a Royal Designer for Industry in 1943. His station designs for London Underground became the corporation's standard design influencing designs by all architects working for the organisation in the 1930s. Many of his buildings have been granted listed building status, protecting them from unapproved alteration. He twice declined the offer of a knighthood.

Early life

Charles Henry Holden was born on 12 May 1875 at Great Lever, Bolton, the fifth and youngest child of Joseph Holden (1842–1918), a draper and milliner, and Ellen (née Broughton, 1841–1890) Holden. Holden's childhood was marred by his father's bankruptcy in 1884 and his mother's death when he was fifteen years old.[1][2] Following the loss of his father's business, the family moved 15 miles (24 km) to St Helens (present-day Merseyside), where his father returned to his earlier trade and worked as an iron turner and fitter and where he attended a number of schools.[1]

He briefly had jobs as a laboratory assistant and a railway clerk in St Helens. During this period he attended draughting classes at the YMCA and considered a career as an engineer in Sir Douglas Fox's practice.[3] In 1891 he began working for his brother-in-law, David Frederick Green, a land surveyor and architect in Bolton.[4] In April 1892 he was articled to Manchester architect Everard W. Leeson and, while training with him, also studied at the Manchester School of Art (1893–94) and Manchester Technical School (1894–96).[note 2]

While working and studying in Manchester, Holden formed friendships with artist Muirhead Bone and his future brother-in-law Francis Dodd.[6] About this time Holden was introduced to the writings of Walt Whitman and became friends with James William Wallace and a number of the members of Bolton's Whitman society known as the "Eagle Street College".[6] Whitman's writings and those of Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Edward Carpenter were major influences on Holden's life.[6] He incorporated many of their philosophies and principles into his style of living and method of working.[7]

In 1895 and 1896 Holden submitted designs to Building News Designing Club competitions using the pseudonym "The Owl".[note 3] Although the number of competing submissions made was not always large, from nine competition entries, Holden won five first places, three second places and one third place.[8][9] In 1897, he entered the competition for the RIBA's prestigious Soane Medallion for student architects. Of fourteen entries, Holden's submission for the competition's subject, a "Provincial Market Hall", came third.[10] Holden described the design as being inspired by the work of John Belcher, Edgar Wood and Arthur Beresford Pite.[11]

Family life

Around 1898 Holden began living with Margaret Steadman (née Macdonald, 1865–1954), a nurse and midwife. They were introduced by Holden's older sister, Alice, and became friends through their common interest in Whitman.[12] Steadman had separated from her husband James Steadman, a university tutor, because of his alcoholism and abuse.[13][note 4] Steadman and her husband were never divorced and, though she and Holden lived as a married couple and Holden referred to her as his wife, the relationship was never formalised, even after James Steadman's death in 1930.[15]

The Holdens lived in suburban Norbiton, Surrey (now Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames) until 1902, when they moved to Codicote in Hertfordshire. Around 1906, they moved to Harmer Green near Welwyn, where Holden designed a house for them.[16] The house was plainly furnished and the couple lived a simple life, described by Janet Ashbee in 1906 as "bananas and brown bread on the table; no hot water; plain living and high thinking and strenuous activity for the betterment of the World".[17] The couple had no children together, though Margaret had a son, Allan, from her marriage.[18][note 5] Charles and Margaret Holden lived at Harmer Green for the rest of their lives.[16]

Works

Early career

Holden left Leeson's practice in 1896 and worked for Jonathan Simpson in Bolton in 1896 and 1897, working on house designs there and at Port Sunlight,[19] before moving to London to work for Arts and Crafts designer Charles Robert Ashbee. His time with Ashbee was short and, in October 1899, he became chief assistant in H. Percy Adams' practice, where he remained for the rest of his career.[16]

A number of Holden's early designs were for hospitals, which Adams' practice specialised in. At this early stage in his career, he produced designs in a variety of architectural styles as circumstances required, reflecting the influences of a number of architects.[16] Holden soon took charge of most of the practice's design work.[20] From 1900 to 1903, Holden studied architecture in the evenings at the Royal Academy School.[21] He also continued to produce designs in his spare time for his brother-in-law and Jonathan Simpson.[22]

His red brick arts and craft façades for the Belgrave Hospital for Children in Kennington, south London (1900–03), were influenced by Philip Webb and Henry Wilson and feature steeply pitched roofs, corner towers and stone window surrounds.[23][24] The building, now converted to apartments, is Grade II* listed.[25][26]

In 1902, Holden won the architectural competition to design the Bristol Central Library. His Tudor Revival façades in bath stone incorporate modernist elements complementing the adjacent Abbey Gate of Bristol Cathedral. The front façade features oriel windows and sculpture groups with Chaucer, Bede and Alfred the Great by Charles Pibworth.[27][28] Internally, the design is classical, with the furniture designed by Holden and the stone carving mostly by William Aumonier.[29] It was described by architectural historian Sir Nikolaus Pevsner as "free Neo-Tudor" and "extremely pretty" and by Andor Gomme as "one of the great masterpieces of the early Modern Movement".[27][30] It has been compared with Charles Rennie Mackintosh's Glasgow School of Art and it is sometimes suggested that Mackintosh's designs for the later part of the school were inspired by Holden's,[25] although Pevsner noted that Mackintosh's designs were in circulation earlier.[30] The building is Grade I listed.[27]

At Midhurst, West Sussex, Holden designed Tudor-style façades for the Sir Ernest Cassel-funded King Edward VII Sanatorium (1903–06). The building features long wings of south-facing rooms to maximise patients' exposure to sunlight and fresh air. The design is in keeping with the building's rural setting, with façades in the local tile-hung style.[25][31] Pevsner called this "certainly one of the best buildings of its date in the country" and "a model of how to build very large institutions".[32] He designed the sanitorium's V-shaped open-air chapel so that it could be used for both outdoor and indoor worship.[25][31] Both buildings are Grade II listed.[33][34] Other hospitals he designed in this period include the British Seamen's Hospital in Istanbul (1903–04) and the Women's Hospital in Soho, central London (1908).[16]

For The Law Society he designed (1902–04) a simplified neoclassical extension to the existing Lewis Vulliamy-designed building in Chancery Lane with external sculptures by Charles Pibworth and a panelled arts and crafts interior with carving by William Aumonier and friezes by Conrad Dressler.[25][35][36] Pevsner considered the façades to be Mannerist: "The fashionable term Mannerism can here be used legitimately; for Holden indeed froze up and invalidated current classical motifs, which is what Mannerist architects did in the Cinquecento."[37]

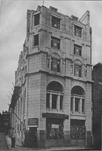

In 1906, Holden won the architectural competition to design a new headquarters for the British Medical Association on the corner of The Strand and Agar Street (now Zimbabwe House). The six-storey L-shaped building replaced a collection of buildings on the site already occupied by the Association and provided it with accommodation for a council chamber, library and offices on the upper floors above space for shops on the ground floor and in the basement.[38] Described by Powers as "classicism reduced to geometric shapes",[25] the first three storeys are clad in grey Cornish granite with Portland stone above.[note 6] Located at second floor level was a controversial series of 7-foot (2.1 m) tall sculptures representing the development of science and the ages of man by Jacob Epstein.[25][40][note 7] The building is Grade II* listed.[41] Alastair Service considered it "perhaps his best London building".[42]

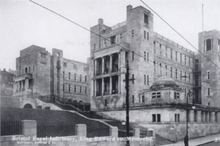

In 1909, Holden won the design competition for an extension to the Bristol Royal Infirmary. Subsequently dedicated to the memory of King Edward VII (died 1910), the extension (1911–12) was built on steeply sloping ground for which Holden designed a linked pair of Portland stone-faced blocks around a courtyard. The plain, abstract blocks have towers on the corners and two-storey loggias, and are a further simplification of Holden's style.[43][note 8]

The practice became Adams & Holden in 1907 when Holden became a partner and Adams, Holden & Pearson when Lionel Pearson became a partner in 1913.[25] In 1913, Holden was awarded the RIBA's Godwin medal and £65 to study architecture abroad. He travelled to America in April 1913 and studied the organisation of household and social science departments at American universities in preparation for his design of the Wren-influenced Kings College for Women, Kensington.[25][44] Other buildings by Holden before the First World War include modernist office buildings in Holborn[45] and Oxford Street,[46] an extension in red brick of Alfred Waterhouse's Shire Hall in Bedford,[47] and Arts and Crafts Sutton Valence School, Kent.[25]

Holden also worked with Epstein on the tomb of Oscar Wilde at Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris (1911–12).[24] In 1915, he was a founding member of the Design and Industries Association and he was a member of the Art Workers' Guild from 1917.[25] Unsuccessful competition entries for which he produced designs include Strathclyde Royal Infirmary (1901), Manchester Royal Infirmary (1904), County Hall (1907), the National Library of Wales (1909), Coventry Town Hall (1911) and the Board of Trade building (1915).[48]

War cemeteries and memorials

The Holdens shared a strong sense of personal duty and service. In the First World War, Margaret Holden joined the "Friends' Emergency Committee for the Assistance of Germans, Austrians and Hungarians in distress" which helped refugees of those countries stranded in London by the conflict. Charles Holden served with the Red Cross's London Ambulance Column as a stretcher-bearer transferring wounded troops from London's stations to its hospitals. Holden also served on the fire watch at St Paul's Cathedral between 1915 and 1917.[49]

On 3 October 1917, Holden was appointed a temporary lieutenant with the army's Directorate of Graves Registration and Enquiries.[50][51] He travelled to the French battlefields for the first time later that month and began planning new cemeteries and expanding existing ones.[52] Holden described his experience:

The country is one vast wilderness, blasted out of recognition where once villages & orchards & fertile land, now tossed about & churned in hopeless disorder with never a landmark as far as the eye can reach & dotted about in the scrub and untidiness of it all are to be seen here & there singly & in groups little white crosses marking the place where men have fallen and been buried.[53]

In September 1918, Holden transferred to the Imperial War Graves Commission (now the Commonwealth War Graves Commission) with the new rank of major.[54] From 1918 until 1928 he worked on 69 Commission cemeteries.[55] Initially, Holden ran the drawing office and worked as the senior design architect under the three principal architects in France and Belgium (Edwin Lutyens, Reginald Blomfield and Herbert Baker).[16][56] Holden worked on the experimental war cemetery at Louvencourt and, according to Geurst and Karol, probably on the one at Forceville that was selected as the prototype for all that followed.[57][58][note 9]

In 1920, he was promoted to be the fourth principal architect.[56][note 10] His work for the Commission included memorials to the New Zealand missing dead at Messines Ridge British Cemetery, and the Buttes New British Cemetery at Zonnebeke.[61] His designs were stripped of ornament, often using simple detailed masses of Portland stone in the construction of the shelters and other architectural elements.[16][62] Philip Longworth's history of the Commission described Holden's pavilions at Wimereux Communal Cemetery as "almost cruelly severe".[63]

In 1922, Holden designed the War Memorial Gateway for Clifton College, Bristol, using a combination of limestone and gritstone to match the Gothic style of the school's buildings.[25][64] For the British War Memorials Committee, he produced a design for a Hall of Remembrance (1918) that would have been in the form of an art gallery,[65] and for New College, Oxford, he created a design for a tiny memorial chapel (1919). Neither was constructed.[66]

London Transport

Through his involvement with the Design and Industries Association Holden met Frank Pick, general manager of the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL).[25] Holden at the time had no experience in designing for transport, but this would change through his collaboration with Pick.[67] In 1923, Pick commissioned Holden to design a façade for a side entrance at Westminster tube station.[68] This was followed in 1924 with an appointment to design the UERL's pavilion for the British Empire Exhibition.[69] Also in 1924, Pick commissioned Holden to design seven new stations in south London for the extension of the City and South London Railway (now part of the Northern line) from Clapham Common to Morden. The designs replaced a set by the UERL's own architect, Stanley Heaps, which Pick had found unsatisfactory.[69] The designs reflect the simple modernist style he was using in France for the war cemeteries; double-height ticket halls are clad in plain Portland stone framing a glazed screen, each adapted to suit the street corner sites of most of the stations.[25] The screens feature the Underground roundel made up in coloured glass panels and are divided by stone columns surmounted by capitals formed as a three-dimensional version of the roundel. Holden also advised Heaps on new façades for a number of the existing stations on the line and produced the design for a new entrance at Bond Street station on the Central London Railway.[68]

During the later 1920s, Holden designed a series of replacement buildings and new façades for station improvements around the UERL's network. Many of these featured Portland stone cladding and variations of the glazed screens developed for the Morden extension.[note 11] At Piccadilly Circus, one of the busiest stations on the system, Holden designed (1925–28) a spacious travertine-lined circulating concourse and ticket hall below the roadway of the junction from which banks of escalators gave access to the platforms below.[72]

In 1926, Holden began the design of a new headquarters for the UERL at 55 Broadway above St. James's Park station. Above the first floor, the steel-framed building was constructed to a cruciform plan and rises in a series of receding stages to a central clock tower 175 feet (53 m) tall.[73] The arrangement maximises daylight to the building's interior without the use of light wells. Like his stations of the period and his pre-First World War commercial buildings, the block is austerely clad in Portland stone. Holden again detailed the façades with commissioned sculptures; Day and Night, two compositions by Epstein, are at first floor level, and a series of eight bas-reliefs at the seventh floor represent the four winds (two for each of the cardinal directions, on each side of the projecting wings).[note 12] The building is Grade I listed.[75]

In 1930, Holden and Pick made a tour of Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden to see the latest developments in modern architecture.[70] The UERL was planning extensions of the Piccadilly line to the west, north-west and north of London, and a new type of station was wanted. Adapting the architectural styles he had seen on the tour, Holden created functional designs composed of simple forms: cylinders, curves and rectangles, built in plain brick, concrete and glass. The extensions to the west and north-west were over existing routes operated by the District line and required a number of stations to be rebuilt to accommodate additional tracks or to replace original, basic buildings. Sudbury Town, the first station to be rebuilt in 1931, formed a template for many of the other new stations that followed: a tall rectangular brick box with a concrete flat roof and panels of vertical glazing to allow light into the interior. The Grade II* listed building was described by Pevsner as "an outstanding example of how satisfying such unpretentious buildings can be, purely through the use of careful details and good proportions."[76][note 13]

For Arnos Grove station, one of eight new stations on the northern extension of the line, Holden modified the rectangular box into a circular drum, a design inspired by Gunnar Asplund's Stockholm Public Library.[25] Also notable on the northern extension is Southgate station; here Holden designed a single-storey circular building with a canopied flat roof. Above this, the central section of roof rises up on a continuous horizontal band of clerestory windows, supported internally by a single central column. The building is topped by an illuminated feature capped with a bronze ball.[77] Other stations show the influence of Willem Marinus Dudok's work in Hilversum, Netherlands.[78] In order to handle such a large volume of work, Holden delegated significant design responsibility to his assistants, such as Charles Hutton, who took the lead on Arnos Grove Station.[79] For some other Piccadilly line stations the design was handled in-house by Stanley Heaps or by other architectural practices. All followed the modern brick, glass and concrete house style defined by Holden,[25] but some lacked Holden's originality and attention to detail; Pick dubbed these "Holdenesque".[69][note 14]

The UERL became part of London Transport in 1933, but the focus remained on high quality design. Under Pick, Holden's attention to detail and idea of integrated design extended to all parts of London's transport network, from designing bus and tram shelters to a new type of six-wheeled omnibus.[81] In the late 1930s, Holden designed replacement stations at Highgate, East Finchley and Finchley Central and new stations at Elstree South and Bushey Heath for the Northern line's Northern Heights plan.[82] Holden's designs incorporated sculpture relevant to the local history of a number of stations: Dick Whittington for Highgate,[83] a Roman centurion at Elstree South[84] and an archer for East Finchley.[85][note 15] Much of the project was postponed shortly after the outbreak of the Second World War and was later cancelled.[87] Only East Finchley station was completed in full with Highgate in part; the other plans were scrapped. East Finchley station is located on an embankment and the platforms are accessed from below. Making use of the station's air-rights, Holden provided staff office space spanning above the tracks accessed through semi-circular glazed stairways from the platforms. Eric Aumonier provided the statue The Archer, a prominent feature of the station.[86]

Holden's last designs for London Transport were three new stations for the Central line extension in north-east London.[88] These were designed in the 1930s, but were also delayed by the war and were not completed until 1947. Post-war austerity measures reduced the quality of the materials used compared with the 1930s stations and the building at Wanstead was adapted from a temporary structure constructed during the line's wartime use as an underground factory.[89] Gants Hill is accessed through subways and has no station building, but is notable for the design of its platform level concourse, which features a barrel vaulted ceiling inspired by stations on the Moscow Metro.[88]

University of London

After the First World War, the University of London needed a replacement for its overcrowded and scattered accommodation in Kensington. A site was acquired in Bloomsbury near the British Museum and Holden was commissioned in 1931 to design the new buildings, partly due to the success of 55 Broadway.[39] His original plan was for a single structure covering the whole site, stretching almost 1,200 feet (370 m) from Montague Place to Torrington Street. It comprised a central spine linked by a series of wings to the perimeter façade and enclosing a series of courtyards. The scheme was to be topped by two towers: a smaller one to the north, and a 19-storey, 210-foot (64 m) tall Senate House.[39]

Construction began in 1932, but due to a shortage of funds, the design was gradually revised and cut back, and only the Senate House and Library were completed in 1937, with the buildings for the Institute of Education and the School of Oriental Studies completed later.[39] The design featured façades of load-bearing brickwork faced with Portland stone. Holden's intention to adorn the building with sculpture was also not fulfilled.[25][24] As he had with his earlier buildings, Holden also prepared the designs for the individual elements of the interior design.[39][90] From its completion until 1957, it was the tallest office building in London.[91]

Senate House divided opinion. Pevsner described its style as "strangely semi-traditional, undecided modernism", and summarised: "The design certainly does not possess the vigour and directness of Charles Holden's smaller Underground stations."[92] Others have described it as Stalinist,[93] or as totalitarian due to its great scale.[39] Functionalist architect Erich Mendelsohn wrote to Holden in 1938 that he was "very much taken and ... convinced that there is no finer building in London."[94] Historian Arnold Whittick described the building as a "static massive pyramid ... obviously designed to last for a thousand years", but thought "the interior is more pleasing than the exterior. There is essentially the atmosphere of dignity, serenity and repose that one associates with the architecture of ancient Greece."[95] The onset of the Second World War prevented any further progress on the full scheme, although Adams, Holden & Pearson did design further buildings for the university in the vicinity.[25]

Town planning

With virtually no new work being commissioned, Holden spent the war years planning for the reconstruction that would be required once it was over.[96] Holden was a member of the RIBA's twelve-man committee which formulated the institute's policy for post-war reconstruction. Holden's town planning ideas involved the relocation of industry out of towns and cities to new industrial centres in the style of Port Sunlight or Bournville where workers could live close to their workplace. The new industrial centres would be linked to the existing towns with new fast roads and reconstruction in town centres would be planned to provide more open space around the administrative centres.[97]

In 1944–45, Holden produced plans for the reconstruction of Canterbury, Kent, with the City Architect Herbert Millson Enderby.[16] Canterbury had been badly damaged by Luftwaffe bombing including the Baedeker raids in May and June 1942. Holden and Enderby aimed to preserve much of the character of the city, but planned for the compulsory purchase of 75 acres (30 ha) of the town centre for large scale reconstruction including a new civic way from the cathedral to a new town hall. Outside the city, they planned bypasses and a ring road at a two-mile (3.2-kilometre) radius of the centre. Although approved by the city council, the plan was widely opposed by residents and freeholders and the "Canterbury Citizens Defence Association" issued an alternative plan before taking control of the council at local elections in November 1945. The change in administration ended the proposals, although a new plan prepared in 1947 without Holden's or Enderby's involvement retained some of their ideas including the ring road.[98]

The City of London's first reconstruction plan was written by the City Engineer F. J. Forty and published in 1944. It had met with considerable criticism and William Morrison, Minister for Town and Country Planning, asked the City of London Corporation to prepare a new plan. Holden was approached, and he accepted provided that William Holford also be appointed. Holden's and Holford's City of London Plan (1946–1947) recommended a relaxation of the strict height limits imposed in the capital and the first use in London of plot ratio calculations in the planning process so that buildings could be designed with floor space of up to five times the ground area.[99][100] For the bomb-devastated area around St Paul's Cathedral, Holden proposed a new precinct around which buildings would be positioned to provide clear views of the cathedral and from which new ceremonial routes would radiate. The heights of buildings would be strictly defined to protect these views. The plan was accepted by the Minister for Town and Country Planning in 1948 and was incorporated into the wider London Development Plan.[101]

In 1947, Holden planned a scheme on behalf of the London County Council for the South Bank of the River Thames between County Hall and Waterloo Bridge,[16][102] including a plan for a concert hall with the council's architect Edwin Williams. The scheme received little attention and was almost immediately superseded by plans to develop the area as the site of the Festival of Britain.[103][note 16] Holden was also architectural and planning consultant to the University of Edinburgh and to the Borough of Tynemouth.[102]

Final years

Although Charles Holden had gradually reduced his workload, he was still continuing to go into the office three days per week during the early 1950s. He did not formally retire until 1958, but even then he visited occasionally. Margaret Holden died in 1954 after a protracted illness which had left her nearly blind since the mid-1940s. In the last decade of his life, Holden was himself physically weaker and was looked after by his niece Minnie Green.[105]

One of Holden's last public engagements was when he acted as a sponsor at the award of the RIBA's Royal Gold Medal to Le Corbusier in 1953.[106] The last project that Holden worked on was a much criticised headquarters building for English Electric in Aldwych, London. In 1952, Adams, Holden & Pearson were appointed by English Electric's chairman, Sir George Nelson, and Holden designed a monolithic stone building around a courtyard. In 1955, the London County Council persuaded English Electric to put the scheme aside and hold a limited architectural competition for a new design. Adams, Holden & Pearson submitted a design, but were beaten by Sir John Burnet, Tait and Partners. When that practice later refused Sir George Nelson's request to redesign the façades, Adams, Holden & Pearson were reappointed and Charles Holden revised his practice's competition entry. The new design was criticised by the Royal Fine Art Commission and a further redesign was carried out by one of Holden's partners to produce the final design, described by Pevsner as "a dull, lifeless building, stone-faced and with nothing to recommend it".[107][note 17]

Holden died on 1 May 1960. His body was cremated at Enfield crematorium and his ashes were spread in the garden of the Friends' Meeting House in Hertford. On 2 June 1960 a memorial service was held at St Pancras New Church, where Holden had designed the altar in 1914. Obituaries were published in daily newspapers The Manchester Guardian, The Times and The Daily Telegraph and in construction industry periodicals including The Builder, Architectural Review, Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects and Journal of the Town Planning Institute. Generally, the obituaries were positive about Holden's early work and the stations for London Underground, were neutral about Senate House and were negative about his practice's later works.[109] The Harmer Green house and most of its contents were auctioned with the proceeds left to family members. Holden also left £8,400 to friends and staff and £2,000 to charity.[110]

Holden on architecture

Holden recognised that his architectural style placed him in "rather a curious position, not quite in the fashion and not quite out of it; not enough of a traditionalist to please the traditionalists and not enough of a modernist to please the modernists."[111] He believed that the principal aim of design was to achieve "fitness for purpose",[69] and repeatedly called for a style of architecture that avoided unnecessary architectural adornment.

In 1905, in an essay titled "If Whitman had been an Architect", Holden made an anonymous plea to architects for a new form of modern architecture: "Often I hear of the glory of the architecture of ancient Greece; of the proud Romans; of sombre Egypt; the praise of vast Byzantium and the lofty Middle Ages, too, I hear. But of the glory of the architecture of the Modern I never hear. Come, you Modern Buildings, come! Throw off your mantle of deceits; your cornices, pilasters, mouldings, swags, scrolls; behind them all, behind your dignified proportions, your picturesque groupings, your arts and crafts prettinesses and exaggerated techniques; behind and beyond them all hides the one I love."[112][note 18]

In his 1936 speech when presented with the RIBA's Royal Gold Medal, Holden defined his position: "It was not so much a matter of creating a new style, as of discarding those incrustations which counted for style ... surface embroidery empty of structural significance". His method was to focus on "those more permanent basic factors of architecture, the plan, and the planes and masses arising out of the plan."[114] He described his ideal building as one "which takes naturally and inevitably the form controlled by the plan and the purpose and the materials. A building which provides opportunities for the exercise and skill and pleasure in work not only to the designer but also for the many craftsmen employed and the occupants of the building."[115]

In a 1957 essay on architecture, he wrote "I don't seek for a style, either ancient or modern, I want an architecture which is through and through good building. A building planned for a specific purpose, constructed in the method and use of materials, old or new, most appropriate to the purpose the building has to serve."[116]

Recognition and legacy

Holden won the RIBA's London Architecture Medal for 1929 (awarded 1931) for 55 Broadway.[16][117] In 1936 he was awarded the RIBA's Royal Gold Medal for his body of work.[102] He was Vice President of the RIBA from 1935–37 and a member of the Royal Fine Art Commission from 1933 to 1947.[102] In 1943 he was appointed a Royal Designer for Industry for the design of transport equipment.[16] He was awarded honorary doctorates by Manchester University in 1936 and London University in 1946.[102] Many of Holden's buildings have been granted listed status, protecting them against demolition and unapproved alteration.

Holden declined the invitation to become a Royal Academician in 1942, having previously been nominated, but refused because of his connection to Epstein.[106][note 19] He twice declined a knighthood, in 1943 and 1951, as he considered it to be at odds with his simple lifestyle and considered architecture a collaborative process.[25][119][note 20]

The RIBA holds a collection of Holden's personal papers and material from Adams, Holden & Pearson. The RIBA staged exhibitions of his work at the Heinz Gallery in 1988 and at the Victoria and Albert Museum between October 2010 and February 2011.[121][122] A public house near Colliers Wood Underground station has been named "The Charles Holden", taking "inspiration" from the architect.[123]

See also

- List of works by Charles Holden, including cemeteries and memorials for the Imperial War Graves Commission.

Notes

- ↑ In architecture, "form" refers to the geometric shapes from which a building's basic design is composed; "massing" refers to the size of the shapes, their bulk and the way in which they are grouped together.

- ↑ Holden took one class at Manchester School of Art in "Architectural History" (grade: excellent). At Manchester Technical School he took classes in "Brickwork and Masonry" and "Building Construction and Drawing" (first class honours in both).[5]

- ↑ The pseudonym was chosen to reflect his working on the designs at night, sometimes until 3 or 4 o'clock.[8]

- ↑ According to a letter from Muirhead Bone to his future wife Gertrude Dodd, James Steadman was twice imprisoned: in Edinburgh for living on the earnings of a prostitute and in Liverpool for embezzlement.[14]

- ↑ Allan Steadman changed his surname to Holden by deed poll in 1918.[13]

- ↑ Holden considered Portland stone "the only stone that washes itself", capable of withstanding London's then smoggy atmosphere.[39]

- ↑ The controversy centred on the supposed shocking nakedness of the statues, but Epstein's sculptures were supported by many leaders of the artistic establishment.[40] In the 1930s, after the building had been sold to the government of Southern Rhodesia, the sculptures were defaced, supposedly to prevent pieces falling off.

- ↑ Today, the adjacent 1960s hospital extension hides most of Holden's building from view.

- ↑ To experiment with layouts and assess the construction costs, three prototype cemeteries were constructed by the Imperial War Graves Commission at Le Tréport, Louvencourt and Forceville. The budget for each cemetery was based on a fixed allowance for each grave it contained, with part of the allowance being allocated to the headstone and the remainder to the cemetery structures and landscaping. To manage costs, Edwin Lutyens' "Stone of Remembrance", which weighed eight tons and cost £500 to make and install, was only provided at larger cemeteries.[59]

- ↑ Holden was the only one of the four principal architects to hold a rank and wear a uniform. His assistants included Wilfred Clement Von Berg and William Harrison Cowlishaw.[60]

- ↑ Holden's station work of this period includes new buildings at West Kensington and, with Stanley Heaps, at Hounslow West and Ealing Common.[70] New entrances or façades were designed for Mansion House, Archway, St. Paul's, Green Park and Holborn.[71] Subsequent reconstructions mean that only West Kensington, Hounslow West, Ealing Common and Holborn remain.

- ↑ The nudity of the Epstein figures again generated controversy, though these have avoided mutilation. Of the eight bas-reliefs, three were carved by Eric Gill and one each by Henry Moore, Eric Aumonier, Allan G Wyon, Samuel Rabinovitch and Alfred Gerrard.[74]

- ↑ Holden called them his "brick boxes with concrete lids".[69] The Sudbury Town pattern was reproduced with adaptations at Acton Town, Alperton, Eastcote, Northfields, Oakwood, Rayners Lane, Sudbury Hill and Turnpike Lane.

- ↑ Stanley Heaps designed stations at Boston Manor, Osterley; Felix Lander designed Park Royal.[80]

- ↑ Dick Whittington was chosen for Highgate because tradition has him "turning again" back to London on Highgate Hill. A centurion was chosen for Elstree South because of the nearby Roman settlement of Sulloniacae.[84] The archer was symbolic of East Finchley's location on the former edge of a royal hunting forest.[86]

- ↑ The concert hall was realised as the Royal Festival Hall by Leslie Martin.[104]

- ↑ The building, later occupied by Citibank, was demolished so that the site could be redeveloped for a hotel.[108]

- ↑ Holden confirmed his authorship in 1951.[113]

- ↑ Henry Moore also refused to become a Royal Academician due to the Academy's treatment of Epstein.[118]

- ↑ Another reason was that, as they were not married, his partner, Margaret, would not have been able to call herself Lady Holden.[120]

References

- 1 2 Karol 2007, pp. 23–25.

- ↑ "No. 25312". The London Gazette. 25 January 1884. pp. 412–413.

- ↑ Karol 2007, p. 26.

- ↑ Karol 2007, p. 28.

- ↑ Karol 2007, pp. 53, 55

- 1 2 3 Karol 2007, p. 32.

- ↑ McCarthy 1981, p. 146.

- 1 2 Karol 2007, p. 58.

- ↑ Allinson 2008, p. 308.

- ↑ Karol 2007, p. 64.

- ↑ Holden, draft letter to John Betjeman, quoted in Karol 2007, p. 65.

- ↑ Karol 2007, pp. 46–47.

- 1 2 Karol 2007, p. 47.

- ↑ Bone, Muirhead (16 January 1902), letter to Gertrude Dodd, quoted in Karol 2007, p. 47.

- ↑ Karol 2007, pp. 47–48.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Hutton & Crawford 2007.

- ↑ Ashbee journals (24 June 1906), quoted in Hutton & Crawford 2007

- ↑ Karol 2007, p. 46.

- ↑ Karol 2007, pp. 51–52.

- ↑ Pevsner 1975, p. 386.

- ↑ Karol 2007, p. 56.

- ↑ Karol 2007, p. 149.

- ↑ Sheppard 1956, pp. 106–08.

- 1 2 3 Stevens Curl 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Powers 2007.

- ↑ Historic England. "Details from image database (204143)". Images of England. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- 1 2 3 Historic England. "Details from image database (379311)". Images of England. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ↑ Foyle, Cherry & Pevsner 2004, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Foyle, Cherry & Pevsner 2004, p. 75.

- 1 2 Pevsner 1975, p. 388.

- 1 2 "King Edward VII Sanatorium". The British Medical Journal. 1 (2372): 1417–1421. 16 June 1906. PMC 2381581

. PMID 20762736. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.2372.1417.

. PMID 20762736. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.2372.1417. - ↑ Nairn & Pevsner 1965, p. 251.

- ↑ Historic England. "Details from image database (301697)". Images of England. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ↑ Historic England. "Details from image database (301698)". Images of England.; Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ↑ Ward-Jackson 2003, p. 80.

- ↑ Historic England. "Details from image database (209062)". Images of England. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ↑ Pevsner 1975, p. 391.

- ↑ "The British Medical Association, The New Offices". The British Medical Journal. 2 (2449): 1661–64. 7 December 1907. PMC 2356978

. PMID 20763579. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.2449.1661.

. PMID 20763579. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.2449.1661. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 Karol 2008, pp. 6–7.

- 1 2 "The Association's New Building". The British Medical Journal. 2 (2479): 40–43. 4 July 1908. PMC 2436923

. PMID 20763951. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.2479.40.

. PMID 20763951. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.2479.40. - ↑ Historic England. "Details from image database (428225)". Images of England. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ↑ Service 1977, p. 112.

- ↑ Foyle, Cherry & Pevsner 2004, pp. 150–51.

- ↑ Karol 2007, pp. 196–97.

- ↑ Historic England. "Details from image database (478240)". Images of England. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ↑ Historic England. "Details from image database (422458)". Images of England. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ↑ Historic England. "Details from image database (35563)". Images of England. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ↑ Karol 2007, pp. 481–82.

- ↑ Karol 2007, pp. 207–08.

- ↑ "No. 30342". The London Gazette (Supplement). 16 October 1917. p. 10744.

- ↑ Karol 2007, p. 209.

- ↑ Geurst 2010, p. 47.

- ↑ Holden (29 October 1917), letter to James Wallace, quoted in Karol 2007, p. 209.

- ↑ Karol 2007, p. 221.

- ↑ Karol 2007, pp. 482–83.

- 1 2 Geurst 2010, p. 60.

- ↑ Geurst 2010, p. 50.

- ↑ Karol 2007, p. 217.

- ↑ Karol 2007, pp. 216–17

- ↑ Karol 2007, p. 223.

- ↑ Glancey 2009.

- ↑ Geurst 2010, pp. 70 & 73.

- ↑ Longworth, Philip (1967), quoted in Karol 2007, p. 231.

- ↑ Historic England. "Details from image database (379327)". Images of England. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ↑ Karol 2007, p. 253.

- ↑ Karol 2007, pp. 231 & 233.

- ↑ "Underground Journeys: Fitness for Purpose". Royal Institute of British Architects. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- 1 2 Day & Reed 2008, p. 96.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Orsini 2010.

- 1 2 Day & Reed 2008, p. 99.

- ↑ Karol 2007, p. 484.

- ↑ Day & Reed 2008, p. 98.

- ↑ Historic England. "Details from image database (208839)". Images of England. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ↑ "55 Broadway". Exploring 20th Century London. London Museums Hub. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ↑ "St James's Park station gets Grade I listing". Department of Culture, Media and Sport. 12 January 2011. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ↑ Cherry & Pevsner 1991, p. 140.

- ↑ Day & Reed 2008, p. 103.

- ↑ Sutcliffe 2006, p. 166.

- ↑ Hanson, Brian (December 1975). "Singing the Body Electric with Charles Holden". Architectural Review. Vol. clviii. pp. 349–56.

- ↑ Day & Reed 2008, p. 114.

- ↑ "Underground Journeys: Integrated Design". Royal Institute of British Architects. Archived from the original on 4 May 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ↑ Beard 2002, p. 82.

- ↑ Day & Reed 2008, p. 140.

- 1 2 Beard 2002, p. 78.

- ↑ Day & Reed 2008, p. 133.

- 1 2 "Eric Aumonier, sculptor, putting the final touches to "The Archer" East Finchley Underground station". Exploring 20th Century London. London Museums Hub. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ↑ Beard 2002, p. 124.

- 1 2 Day & Reed 2008, p. 149.

- ↑ Emmerson & Beard 2004, p. 119.

- ↑ Rice 2003.

- ↑ Wright 2006, p. 34.

- ↑ Cherry & Pevsner 1998, p. 276.

- ↑ Jenkins 2005.

- ↑ Mendelsohn, Erich (1938), letter to Holden, quoted in Karol 2008, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Whittick 1974, p. 515.

- ↑ Karol 2007, pp. 430–31.

- ↑ Karol 2007, pp. 433–35.

- ↑ Karol 2007, pp. 437–39.

- ↑ Sutcliffe 2006, p. 185.

- ↑ Karol 2007, p. 447.

- ↑ Karol 2007, p. 453, 459–60.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Who Was Who 2007.

- ↑ Karol 2007, p. 463.

- ↑ Sutcliffe 2006, p. 178

- ↑ Karol 2007, pp. 17 & 466–67.

- 1 2 Karol 2007, p. 472.

- ↑ Pevsner & Cherry 1973, p. 379.

- ↑ Eade, Christine (6 November 2009). "Silken hotel seeks £110m-plus purse". Property Week. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ↑ Karol 2007, pp. 469 & 471.

- ↑ Karol 2007, p. 469.

- ↑ Holden, quoted in Karol 2008, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Anon (Holden, Charles) (June 1905). "If Whitman had been an Architect". Architectural Review. p. 258. Quoted in Karol 2007, pp. 167 & 173.

- ↑ Karol 2007, p. 174

- ↑ Holden, Charles (1936). "RIBA Journal". xliii (3rd Series): 623.

- ↑ Holden, quoted in Glancey 2007.

- ↑ Holden, Charles (1957). "The Kind of Architecture we want in Britain". Architectural Review. Quoted in Karol 2007, p. 9.

- ↑ "Architectural Medal, Underground Railway Offices in Westminster". The Times (45725): 10. 20 January 1931. Retrieved 17 September 2010. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Karol 2007, p. 467

- ↑ Blacker 2004.

- ↑ Karol 2007, p. 431

- ↑ Karol 2007, p. 17.

- ↑ "Underground Journeys: Charles Holden's designs for London Transport". Royal Institute of British Architects. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ↑ "The Charles Holden". The New Pub Company. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

Bibliography

- Allinson, Kenneth (2008). Architects and Architecture of London. Architectural Press. ISBN 978-0-7506-8337-1. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- Beard, Tony (2002). By Tube Beyond Edgware. Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-85414-246-7.

- Blacker, Zöe (8 January 2004). "Architecture gains two honours". Architects' Journal. Retrieved 25 September 2010. (Subscription required (help)).

- Cherry, Bridget; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1991). London 3: North West. The Buildings of England. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09652-1. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- Cherry, Bridget; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1998). London 4: North. The Buildings of England. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09653-8. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- Day, John R; Reed, John (2008) [1963]. The Story of London's Underground. Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-85414-316-7.

- Emmerson, Andrew; Beard, Tony (2004). London's Secret Tubes. Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-85414-283-2.

- Foyle, Andrew; Cherry, Bridget; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2004). Bristol. Pevsner Architectural Guides. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10442-4. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- Geurst, Jeroen (2010). Cemeteries of the Great War by Sir Edwin Lutyens. 010 Publishers. ISBN 978-90-6450-715-1. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- Glancey, Jonathan (16 October 2007). "An architecture free from fads and aesthetic conceits". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- Glancey, Jonathan (5 November 2009). "Jonathan Glancey on architect Charles Holden". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- Hutton, Charles; Crawford, Alan (October 2007). "Holden, Charles Henry (1875–1960), architect". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33927. Retrieved 25 September 2010. (subscription or UK public library membership required).

- Jenkins, Simon (2 December 2005). "It's time to knock down Hitler's headquarters and start again". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- Karol, Eitan (2007). Charles Holden: Architect. Shaun Tyas. ISBN 978-1-900289-81-8.

- Karol, Eitan (2008). "Naked and unashamed: Charles Holden in Bloomsbury" (PDF). Past and Future. The Institute of Historical Research (4). Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- McCarthy, Fiona (1981). The Simply Life: C.R. Ashbee in the Cotswolds. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04369-5. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- Nairn, Ian; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1965). Sussex. The Buildings of England. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-071028-1.

- Orsini, Fiona (2010). Underground Journeys: Charles Holden's designs for London Transport. V&A + RIBA Architecture Partnership. Archived from the original on 2 May 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Cherry, Bridget (1973). London: The Cities of London and Westminster. The Buildings of England. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-071012-0. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- Pevsner, Nickolaus (1975). "Charles Holden's Early Works". In Service, Alastair. Edwardian Architecture and its Origins. Architectural Press. ISBN 978-0-85139-362-9.

- Powers, Alan (2007). "Holden, Charles (Henry)". Grove Art Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 25 September 2010. (Subscription required (help)).

- Rice, Ian (September 2003). "Building of the Month". Twentieth Century Society. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- Service, Alastair (1977). Edwardian architecture: a handbook to building design in Britain 1890–1914. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-519982-6.

- Sheppard, F. H. W., ed. (1956). "Brixton: The Wright estate". Survey of London: volume 26: Lambeth: Southern area. English Heritage. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- Stevens Curl, James (2006). Holden, Charles Henry. A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860678-9. doi:10.1093/acref/9780198606789.001.0001. (Subscription required (help)).

- Sutcliffe, Anthony (2006). London: An Architectural History. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11006-7. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- Ward-Jackson, Philip (2003). Public Sculpture of the City of London. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-0-85323-977-2. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- Whittick, Arnold (1974). European architecture in the twentieth century. Leonard Hill Books. ISBN 978-0-200-04017-4. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- Wright, Herbert (2006). London High. Francis Lincoln. ISBN 978-0-7112-2695-1. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- "Holden, Charles". Who Was Who. Oxford University Press/A & C Black. 2007. Retrieved 25 September 2010. (Subscription required (help)).

Further reading

- Lawrence, David (2008). Bright Underground Spaces: The Railway Stations of Charles Holden. Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-85414-320-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

General

- Charlesholden.com (brief introduction to Holden)

- Bristol Central Library (looking at Buildings guide to one of Holden's buildings)

- Underground Journeys: Charles Holden's designs for London Transport (online exhibition from the Royal Institute of British Architects)

- Map of London Underground structures that were designed or inspired by Holden (from the RIBA exhibition)

- "Archival material relating to Charles Holden". UK National Archives.

Image galleries

- London Transport Museum Photographic Archive (search results for "Charles Holden")

- RIBA photographic archive (search results for "Charles Holden")

- Charlesholden.com (image gallery)

Portraits

- Charles Holden in later life (from the LTM Photographic Archive)

- Charles Holden by Francis Dodd, 1915 (from the National Portrait Gallery)

.jpg)