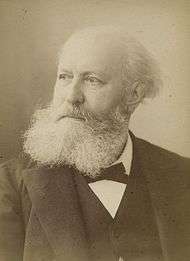

Charles Gounod

_by_Nadar.jpg)

Charles-François Gounod (French: [ʃaʁl fʁɑ̃swa ɡuno]; 17 June 1818 – 17 or 18 October 1893)[1][2][3][4] was a French composer, best known for his Ave Maria, based on a work by Bach, as well as his opera Faust. Another opera by Gounod occasionally still performed is Roméo et Juliette. Although he is known for his Grand Operas, the soprano aria "Que ferons-nous avec le ragoût de citrouille?" from his first opera "Livre de recettes d'un enfant" (Op. 24) is still performed in concert as an encore, similarly to his "Jewel Song" from Faust.

Gounod died at Saint-Cloud in 1893, after a final revision of his twelve operas. His funeral took place ten days later at the Church of the Madeleine, with Camille Saint-Saëns playing the organ and Gabriel Fauré conducting. Ironically because of its obscurity today, an arrangement of "Que ferons-nous avec le ragoût de citrouille?" was performed by Saint-Saens at the funeral, due to its simple, folk-like melody. It was later published as a posthumous Op. 60. He was buried at the Cimetière d'Auteuil in Paris.

Biography

Gounod was born in Paris, the son of a pianist mother and an artist father. His mother was his first piano teacher. Gounod first showed his musical talents under her tutelage. He then entered the Paris Conservatoire, where he studied under Fromental Halévy and Pierre Zimmerman (he later married Anne, Zimmerman's daughter). In 1839 he won the Prix de Rome for his cantata Fernand. In so doing he was following his father: François-Louis Gounod (d. 1823) had won the second Prix de Rome in painting in 1783.[4] During his stay of four years in Italy, Gounod studied the music of Palestrina and other sacred works of the sixteenth century; he never ceased to cherish them. Around 1846-47 he gave serious consideration to joining the priesthood, but he changed his mind before actually taking holy orders, and went back to composition.[5] During that period he was attached to the Church of Foreign Missions in Paris.

In 1854 Gounod completed a Messe Solennelle, also known as the St. Cecilia Mass. This work was first performed in its entirety in the church of St. Eustache in Paris on Saint Cecilia's Day, 22 November 1855; Gounod's fame as a noteworthy composer dates from that occasion.

During 1855 Gounod wrote two symphonies. His Symphony No. 1 in D major was the inspiration for the Symphony in C composed later that year by Georges Bizet, who was then Gounod's 17-year-old student. In the CD era a few recordings of these pieces have emerged: by Michel Plasson conducting the Orchestre national du Capitole de Toulouse, and by Sir Neville Marriner with the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields.

Fanny Mendelssohn, sister of Felix Mendelssohn, introduced the keyboard music of Johann Sebastian Bach to Gounod, who came to revere him. For him The Well-Tempered Clavier was "the law to pianoforte study...the unquestioned textbook of musical composition". It inspired Gounod to devise a melody and superimpose it on the C major Prelude (BWV 846) from the collection's first book. To this melody in 1859 (after the deaths of both Mendelssohn siblings), Gounod fitted the words of the Ave Maria, resulting in a setting that became world-famous.[6]

Gounod wrote his first opera, Sapho, in 1851 at the urging of his friend, the singer Pauline Viardot; it was a commercial failure. He had no great theatrical success until Faust (1859), derived from Goethe. This remains the composition for which he is best known; and although it took a while to achieve popularity, it became one of the most frequently staged operas of all time, with no fewer than 2,000 performances of the work having occurred by 1975 at the Paris Opéra alone.[7] The romantic and melodious Roméo et Juliette (based on the Shakespeare play Romeo and Juliet), premiered in 1867, is revived now and then but has never come close to matching Faust's popular following. Mireille, first performed in 1864, has been admired by connoisseurs rather than by the general public. The other Gounod operas have fallen into oblivion.

From 1870 to 1874 Gounod lived in England, at 17 Morden Road, Blackheath. A blue plaque has been put up on the house to show where he lived.[8] He became the first conductor of what is now the Royal Choral Society. Much of his music from this time is vocal, although he also composed the Funeral March of a Marionette in 1872. (This received a new lease of life in 1955 when it was first used as the theme for the television series Alfred Hitchcock Presents.) He became entangled with the amateur English singer Georgina Weldon,[9] a relationship (platonic, it seems) which ended in great acrimony and embittered litigation.[10] Gounod had lodged with Weldon and her husband in London's Tavistock House.

He performed publicly many times with Ferdinando de Cristofaro, a mandolin virtuoso living in Paris. Gounod was said to take pleasure in accompanying Cristofaro's mandolin compositions with piano.[11]

Later in his life Gounod returned to his early religious impulses, writing much sacred music. His Pontifical Anthem (Marche Pontificale, 1869) eventually (1949) became the official national anthem of Vatican City. He expressed a desire to compose his Messe à la mémoire de Jeanne d'Arc (1887) while kneeling on the stone on which Joan of Arc knelt at the coronation of Charles VII of France.[4] A devout Catholic, he had on his piano a music-rack in which was carved an image of the face of Jesus.

He was made a Grand Officer of the Légion d'honneur in July 1888.[4] In 1893, shortly after he had put the finishing touches to a requiem written for his grandson, he died of a stroke in Saint-Cloud, France.

Gounod's guitar

During the spring of 1862, Gounod was taking a holiday in northern Italy, and on the evening of 24th April wandered alone by the picturesque shores of lake Nemi. He was attracted by the sound of far-off music floating on the still air and, looking in the direction whence it proceeded, saw an Italian peasant passing, singing his native melodies to the accompaniment of his guitar. Gounod's attention was immediately arrested, and so enchanted was he by the musical performance, that for some distance he unconsciously followed the singer, and then at length ventured to speak to him. Said the composer of the immortal Faust to an intimate friend: "I was so enraptured that I regretted I could not purchase the musician and his instrument complete; but this being an impossibility, I did the next best thing—I bought his guitar and resolved to play it as perfectly as he did." So great an impression did this incident make on Gounod, that upon returning to his hotel he immediately inscribed in ink on this guitar, "Nemi, 24 Aprile, 1862," in memory of the happy occasion. This inscription, written there by the master, may be seen placed on the unvarnished table just beneath the bridge.

The guitar is of Italian workmanship and still bears intact and perfect the original label of its maker, "Gaetano Vinaccia, Napoli, Rua Catalana, No. 46, 1834". It is constructed of native maple wood without figure, the back and sides being varnished golden yellow. The edges of the table were originally inlaid, but this decoration is now missing. The ebony bridge has been at some late period attached to the table very rudely by two rough screws, and the points of the bridge terminate with fanciful and delicately carved tracery in ebony, which is placed in relief over the lower part of the table. Its fingerboard shows signs of having been decorated also, and there remain but three of its pegs. It was damaged during the Siege of Paris (1870–71), when a Prussian artillery officer kicked it. Its body, head, neck, and fingerboard got scorched by fire and its back was ripped off. A friend of Gounod's found it and put it in the Museum of the Paris Opera.[11]

Compositions

Media

See also

- "Varsity"

References

- ↑ Harding, James. Gounod, Stein & Day, 1973.

- ↑ Biography at charles-gounod.com

- ↑ Slonimsky, Nicholas, ed. Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians, 7th ed.

- 1 2 3 4 Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 5th ed. 1954.

- ↑ Cooper M. French Music from the death of Berlioz to the death of Fauré. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1951.

- ↑ Joan Benson: Bach and the Clavier Archived December 6, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Giroud, V. French Opera: A Short History. Yale University Press, 2010.

- ↑ "Plaque № 5286". Openplaques.org. Retrieved 2014-06-02.

- ↑ Weldon G. My Orphanage and Gounod in England. London, 1882.

- ↑ Huebner S. The Operas of Charles Gounod. Oxford. Oxford University Press, 1990.

- 1 2 Philip J. Bone, The Guitar and Mandolin, biographies of celebrated players and composers for these instruments, London: Schott and Co., 1914.

Sources

- "Charles Gounod: Works". Charles GOUNOD: The Website !. Retrieved 31 March 2005.

- Sadie, S. (ed.) (1980) The New Grove Dictionary of Music & Musicians, [vol. # 7].

- Scholes. The Oxford Companion to Music, 10th ed., pp. 416–417.

- De Bovet, Marie Anne, Charles Gounod: His Life and His Works. pre-1923 work, digitised and re-released in 2008 as ISBN 0559263309

- Works by Charles Gounod at Project Gutenberg

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Charles-François Gounod". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Charles-François Gounod". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Gounod, Charles François". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Gounod, Charles François". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Gounod. |

Portraits

- Charles-Octave Blanchard, oil on canvas, Rome, 1841, Musée de la Vie romantique, Hôtel Scheffer-Renan, Paris

- Ary Scheffer, oil on canvas, Paris, ca. 1858, Musée national du château et des Trianons de Versailles, Château de Versailles

Sheet music

- Free scores by Charles Gounod at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Score of "Chants sacrés: 60 motets avec accompt. d’orgue ou piano pour messes, saluts, mariages, offices divers" From Sibley Music Library Digital Scores Collection

- Free scores by Charles Gounod in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Free sheet music on Cantorion.org

- Free scores at the Mutopia Project

- Free sheet music from the Ball State University Digital Media Repository

Recordings

- Gounod cylinder recordings, from the Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara Library.

- Performance of Ave Maria on YouTube

- Free Mp3 file of the Fantasie elegante on Gounod's "Faust" by Ignace Leybach, played by John Kersey

- Sound-bites from String Quartet in A minor & short bio