Chandra X-ray Observatory

|

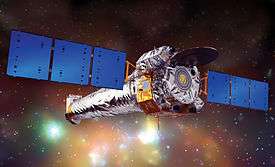

Illustration of Chandra | |||||||||||

| Names | Advanced X-ray Astrophysics Facility (AXAF) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mission type | X-ray astronomy | ||||||||||

| Operator | NASA / SAO / CXC | ||||||||||

| COSPAR ID | 1999-040B | ||||||||||

| SATCAT no. | 25867 | ||||||||||

| Website | http://chandra.harvard.edu/ | ||||||||||

| Mission duration |

Planned: 5 years Elapsed: 18 years, 23 days | ||||||||||

| Spacecraft properties | |||||||||||

| Manufacturer | TRW Inc. | ||||||||||

| Launch mass | 4,790 kg (10,560 lb)[1] | ||||||||||

| Dimensions | 13.8 × 19.5 m (45.3 × 64.0 ft)[1] | ||||||||||

| Power | 2350 W[1] | ||||||||||

| Start of mission | |||||||||||

| Launch date | July 23, 1999, 04:31 UTC | ||||||||||

| Rocket | Space Shuttle Columbia (STS-93) | ||||||||||

| Launch site | Kennedy LC-39B | ||||||||||

| Orbital parameters | |||||||||||

| Reference system | Geocentric | ||||||||||

| Regime | Highly elliptical | ||||||||||

| Semi-major axis | 80,795.9 km (50,204.2 mi) | ||||||||||

| Eccentricity | 0.743972 | ||||||||||

| Perigee | 14,307.9 km (8,890.5 mi) | ||||||||||

| Apogee | 134,527.6 km (83,591.6 mi) | ||||||||||

| Inclination | 76.7156° | ||||||||||

| Period | 3809.3 min | ||||||||||

| RAAN | 305.3107° | ||||||||||

| Argument of perigee | 267.2574° | ||||||||||

| Mean anomaly | 0.3010° | ||||||||||

| Mean motion | 0.3780 rev/day | ||||||||||

| Epoch | September 4, 2015, 04:37:54 UTC[2] | ||||||||||

| Revolution no. | 1358 | ||||||||||

| Main telescope | |||||||||||

| Type | Wolter type 1[3] | ||||||||||

| Diameter | 1.2 m (3.9 ft)[1] | ||||||||||

| Focal length | 10.0 m (32.8 ft)[1] | ||||||||||

| Collecting area | 0.04 m2 (0.43 sq ft)[1] | ||||||||||

| Wavelengths | X-ray: 0.12–12 nm (0.1–10 keV)[4] | ||||||||||

| Resolution | 0.5 arcsec[1] | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The Chandra X-ray Observatory (CXO), previously known as the Advanced X-ray Astrophysics Facility (AXAF), is a Flagship-class space observatory launched on STS-93 by NASA on July 23, 1999. Chandra is sensitive to X-ray sources 100 times fainter than any previous X-ray telescope, enabled by the high angular resolution of its mirrors. Since the Earth's atmosphere absorbs the vast majority of X-rays, they are not detectable from Earth-based telescopes; therefore space-based telescopes are required to make these observations. Chandra is an Earth satellite in a 64-hour orbit, and its mission is ongoing as of 2017.

Chandra is one of the Great Observatories, along with the Hubble Space Telescope, Compton Gamma Ray Observatory (1991–2000), and the Spitzer Space Telescope. The telescope is named after the Nobel Prize-winning Indian-American astrophysicist Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar.[5]

History

In 1976 the Chandra X-ray Observatory (called AXAF at the time) was proposed to NASA by Riccardo Giacconi and Harvey Tananbaum. Preliminary work began the following year at Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) and the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO). In the meantime, in 1978, NASA launched the first imaging X-ray telescope, Einstein (HEAO-2), into orbit. Work continued on the AXAF project throughout the 1980s and 1990s. In 1992, to reduce costs, the spacecraft was redesigned. Four of the twelve planned mirrors were eliminated, as were two of the six scientific instruments. AXAF's planned orbit was changed to an elliptical one, reaching one third of the way to the Moon's at its farthest point. This eliminated the possibility of improvement or repair by the space shuttle but put the observatory above the Earth's radiation belts for most of its orbit. AXAF was assembled and tested by TRW (now Northrop Grumman Aerospace Systems) in Redondo Beach, California.

AXAF was renamed Chandra as part of a contest held by NASA in 1998, which drew more than 6,000 submissions worldwide.[6] The contest winners, Jatila van der Veen and Tyrel Johnson (then a high school teacher and high school student, respectively), suggested the name in honor of Nobel Prize–winning Indian-American astrophysicist Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar. He is known for his work in determining the maximum mass of white dwarf stars, leading to greater understanding of high energy astronomical phenomena such as neutron stars and black holes.[5]

Originally scheduled to be launched in December 1998,[6] the spacecraft was delayed several months, eventually being launched in July 1999 by Space Shuttle Columbia during STS-93. At 22,753 kilograms (50,162 lb), it was the heaviest payload ever launched by the shuttle, a consequence of the two-stage Inertial Upper Stage booster rocket system needed to transport the spacecraft to its high orbit.

Chandra has been returning data since the month after it launched. It is operated by the SAO at the Chandra X-ray Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts, with assistance from MIT and Northrop Grumman Space Technology. The ACIS CCDs suffered particle damage during early radiation belt passages. To prevent further damage, the instrument is now removed from the telescope's focal plane during passages.

Although Chandra was initially given an expected lifetime of 5 years, on September 4, 2001 NASA extended its lifetime to 10 years "based on the observatory's outstanding results."[7] Physically Chandra could last much longer. A 2004 study performed at the Chandra X-ray Center indicated that the observatory could last at least 15 years.[8]

In July 2008, the International X-ray Observatory, a joint project between ESA, NASA and JAXA, was proposed as the next major X-ray observatory but was later cancelled.[9] ESA later resurrected the project as the Advanced Telescope for High Energy Astrophysics (ATHENA) with a proposed launch in 2028.[10]

Examples discoveries

The data gathered by Chandra has greatly advanced the field of X-ray astronomy. Here are some examples of discoveries supported by observations from Chandra:

- The first light image, of supernova remnant Cassiopeia A, gave astronomers their first glimpse of the compact object at the center of the remnant, probably a neutron star or black hole. (Pavlov, et al., 2000)

- In the Crab Nebula, another supernova remnant, Chandra showed a never-before-seen ring around the central pulsar and jets that had only been partially seen by earlier telescopes. (Weisskopf, et al., 2000)

- The first X-ray emission was seen from the supermassive black hole, Sagittarius A*, at the center of the Milky Way. (Baganoff, et al., 2001)

- Chandra found much more cool gas than expected spiraling into the center of the Andromeda Galaxy.

- Pressure fronts were observed in detail for the first time in Abell 2142, where clusters of galaxies are merging.

- The earliest images in X-rays of the shock wave of a supernova were taken of SN 1987A.

- Chandra showed for the first time the shadow of a small galaxy as it is being cannibalized by a larger one, in an image of Perseus A.

- A new type of black hole was discovered in galaxy M82, mid-mass objects purported to be the missing link between stellar-sized black holes and super massive black holes. (Griffiths, et al., 2000)

- X-ray emission lines were associated for the first time with a gamma-ray burst, Beethoven Burst GRB 991216. (Piro, et al., 2000)

- High school students, using Chandra data, discovered a neutron star in supernova remnant IC 443.[11]

- Observations by Chandra and BeppoSAX suggest that gamma-ray bursts occur in star-forming regions.

- Chandra data suggested that RX J1856.5-3754 and 3C58, previously thought to be pulsars, might be even denser objects: quark stars. These results are still debated.

- Sound waves from violent activity around a super massive black hole were observed in the Perseus Cluster (2003).

- TWA 5B, a brown dwarf, was seen orbiting a binary system of Sun-like stars.

- Nearly all stars on the main sequence are X-ray emitters. (Schmitt & Liefke, 2004)

- The X-ray shadow of Titan was seen when it transitted the Crab Nebula.

- X-ray emissions from materials falling from a protoplanetary disc into a star. (Kastner, et al., 2004)

- Hubble constant measured to be 76.9 km/s/Mpc using Sunyaev-Zel'dovich effect.

- 2006 Chandra found strong evidence that dark matter exists by observing super cluster collision

- 2006 X-ray emitting loops, rings and filaments discovered around a super massive black hole within Messier 87 imply the presence of pressure waves, shock waves and sound waves. The evolution of Messier 87 may have been dramatically affected.[12]

- Observations of the Bullet cluster put limits on the cross-section of the self-interaction of dark matter.[13]

- "The Hand of God" photograph of PSR B1509-58.

- Jupiter's x-rays coming from poles, not auroral ring.[14]

- A large halo of hot gas was found surrounding the Milky Way.[15]

- Extremely dense and luminous dwarf galaxy M60-UCD1 observed.[16]

- On January 5, 2015, NASA reported that CXO observed an X-ray flare 400 times brighter than usual, a record-breaker, from Sagittarius A*, a supermassive black hole in the center of the Milky Way galaxy. The unusual event may have been caused by the breaking apart of an asteroid falling into the black hole or by the entanglement of magnetic field lines within gas flowing into Sagittarius A*, according to astronomers.[17]

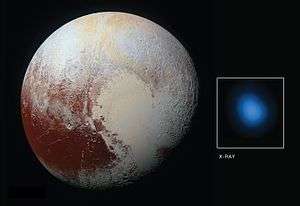

- In September 2016, it was announced that Chandra had detected X-ray emissions from Pluto, the first detection of X-rays from a Kuiper belt object. Chandra had made the observations in 2014 and 2015, supporting the New Horizons spacecraft for its July 2015 encounter.[18]

Technical description

Unlike optical telescopes which possess simple aluminized parabolic surfaces (mirrors), X-ray telescopes generally use a Wolter telescope consisting of nested cylindrical paraboloid and hyperboloid surfaces coated with iridium or gold. X-ray photons would be absorbed by normal mirror surfaces, so mirrors with a low grazing angle are necessary to reflect them. Chandra uses four pairs of nested mirrors, together with their support structure, called the High Resolution Mirror Assembly (HRMA); the mirror substrate is 2 cm-thick glass, with the reflecting surface a 33 nm iridium coating, and the diameters are 65 cm, 87 cm, 99 cm and 123 cm.[19] The thick substrate and particularly careful polishing allowed a very precise optical surface, which is responsible for Chandra's unmatched resolution: between 80% and 95% of the incoming X-ray energy is focused into a one-arcsecond circle. However, the thickness of the substrates limit the proportion of the aperture which is filled, leading to the low collecting area compared to XMM-Newton.

Chandra's highly elliptical orbit allows it to observe continuously for up to 55 hours of its 65-hour orbital period. At its furthest orbital point from Earth, Chandra is one of the most distant Earth-orbiting satellites. This orbit takes it beyond the geostationary satellites and beyond the outer Van Allen belt.[20]

With an angular resolution of 0.5 arcsecond (2.4 µrad), Chandra possesses a resolution over 1000 times better than that of the first orbiting X-ray telescope.

CXO uses mechanical gyroscopes,[21] which are sensors that help determine what direction the telescope is pointed.[22] Other navigation and orientation systems on board CXO include an aspect camera, Earth and Sun sensors, and reaction wheels. It also has two sets of thrusters, one for movement and another for offloading momentum.[22]

Instruments

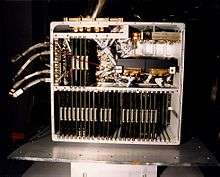

The Science Instrument Module (SIM) holds the two focal plane instruments, the Advanced CCD Imaging Spectrometer (ACIS) and the High Resolution Camera (HRC), moving whichever is called for into position during an observation.

ACIS consists of 10 CCD chips and provides images as well as spectral information of the object observed. It operates in the photon energy range of 0.2–10 keV. HRC has two micro-channel plate components and images over the range of 0.1–10 keV. It also has a time resolution of 16 microseconds. Both of these instruments can be used on their own or in conjunction with one of the observatory's two transmission gratings.

The transmission gratings, which swing into the optical path behind the mirrors, provide Chandra with high resolution spectroscopy. The High Energy Transmission Grating Spectrometer (HETGS) works over 0.4–10 keV and has a spectral resolution of 60–1000. The Low Energy Transmission Grating Spectrometer (LETGS) has a range of 0.09–3 keV and a resolution of 40–2000.

Summary:[23]

- High Resolution Camera (HRC)

- Advanced CCD Imaging Spectrometer (ACIS)

- High Energy Transmission Grating Spectrometer (HETGS)

- Low Energy Transmission Grating Spectrometer (LETGS)

Gallery

X-Rays from Pluto.

X-Rays from Pluto. Jupiter in X-ray light.

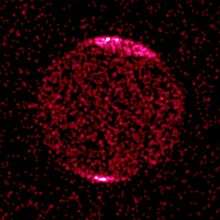

Jupiter in X-ray light. Tycho Supernova remnant in X-ray light.

Tycho Supernova remnant in X-ray light.

CXO orbit as of January 7, 2014.

CXO orbit as of January 7, 2014. M31 Core in X-ray light.

M31 Core in X-ray light. PSR B1509-58 - red, green and blue/max energy.

PSR B1509-58 - red, green and blue/max energy. Turbulence may prevent galaxy clusters from cooling.

Turbulence may prevent galaxy clusters from cooling.

SNR 0519-69.0 - remains of an exploding star in the Large Magellanic Cloud.

SNR 0519-69.0 - remains of an exploding star in the Large Magellanic Cloud. Images released to celebrate the International Year of Light 2015.

Images released to celebrate the International Year of Light 2015.

GK Persei: Nova of 1901.

GK Persei: Nova of 1901. X-ray light rings from a neutron star in Circinus X-1.

X-ray light rings from a neutron star in Circinus X-1. Cygnus X-1, first strong black hole discovered.

Cygnus X-1, first strong black hole discovered.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Chandra Specifications". NASA/Harvard. Retrieved September 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Chandra X-Ray Observatory - Orbit". Heavens Above. September 3, 2015. Retrieved September 3, 2015.

- ↑ "The Chandra X-ray Observatory: Overview". Chandra X-ray Center. Retrieved September 3, 2015.

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian (2012). The Dictionary of Astronomy (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-19-960905-5.

- 1 2 "And the co-winners are...". Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. 1998. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- 1 2 Tucker, Wallace (October 31, 2013). "Tyrel Johnson & Jatila van der Veen - Winners of the Chandra-Naming Contest - Where Are They Now?". Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- ↑ "Chandra's Mission Extended to 2009". Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. September 28, 2001.

- ↑ Schwartz, Daniel A. (August 2004). "The Development and Scientific Impact of the Chandra X-Ray Observatory". International Journal of Modern Physics D. 13 (7): 1239–1248. Bibcode:2004IJMPD..13.1239S. arXiv:astro-ph/0402275

. doi:10.1142/S0218271804005377.

. doi:10.1142/S0218271804005377. - ↑ "International X-ray Observatory". NASA.gov.

- ↑ Howell, Elizabeth (November 1, 2013). "X-ray Space Telescope of the Future Could Launch in 2028". Space.com. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ↑ "Students Using NASA and NSF Data Make Stellar Discovery; Win Science Team Competition" (Press release). NASA. December 12, 2000. Release 00-195. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ↑ Roy, Steve; Watzke, Megan (October 2006). "Chandra Reviews Black Hole Musical: Epic But Off-Key" (Press release). Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

- ↑ Madejski, Greg (2005). Recent and Future Observations in the X-ray and Gamma-ray Bands: Chandra, Suzaku, GLAST, and NuSTAR. Astrophysical Sources of High Energy Particles and Radiation. June 20–24, 2005. Torun, Poland. AIP Conference Proceedings. 801. p. 21. arXiv:astro-ph/0512012

. doi:10.1063/1.2141828.

. doi:10.1063/1.2141828. - ↑ "Puzzling X-rays from Jupiter". NASA.gov. March 7, 2002.

- ↑ Harrington, J. D.; Anderson, Janet; Edmonds, Peter (September 24, 2012). "NASA's Chandra Shows Milky Way is Surrounded by Halo of Hot Gas". NASA.gov.

- ↑ "M60-UCD1: An Ultra-Compact Dwarf Galaxy". NASA.gov. September 24, 2013.

- 1 2 Chou, Felicia; Anderson, Janet; Watzke, Megan (January 5, 2015). "RELEASE 15-001 - NASA’s Chandra Detects Record-Breaking Outburst from Milky Way’s Black Hole". NASA. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ↑ "X-Ray Detection Sheds New Light on Pluto". Applied Physics Laboratory. September 14, 2016. Retrieved November 17, 2016.

- ↑ Gaetz, T. J.; Jerius, Diab (January 28, 2005). "The HRMA User's Guide" (PDF). Chandra X-ray Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 10, 2006.

- ↑ Gott, J. Richard; Juric, Mario (2006). "Logarithmic Map of the Universe". Princeton University.

- ↑ "Technical Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)". James Webb Space Telescope. NASA. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- 1 2 "Spacecraft: Motion, Heat, and Energy". Chandra X-ray Observatory. NASA. 17 March 2014. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ↑ "Science Instruments". Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Retrieved November 17, 2016.

Further reading

- Griffiths, R. E.; Ptak, A.; Feigelson, E. D.; Garmire, G.; Townsley, L.; Brandt, W. N.; Sambruna, R.; Bregman, J. N. (2000). "Hot plasma and black hole binaries in starburst galaxy M82". Science. 290 (5495): 1325–1328. Bibcode:2000Sci...290.1325G. PMID 11082054. doi:10.1126/science.290.5495.1325.

- Pavlov, G. G.; Zavlin, V. E.; Aschenbach, B.; Trumper, J.; Sanwal, D. (2000). "The Compact Central Object in Cassiopeia A: A Neutron Star with Hot Polar Caps or a Black Hole?". The Astrophysical Journal. 531 (1): L53–L56. Bibcode:2000ApJ...531L..53P. PMID 10673413. arXiv:astro-ph/9912024

. doi:10.1086/312521.

. doi:10.1086/312521. - Piro, L.; Garmire, G.; Garcia, M.; Stratta, G.; Costa, E.; Feroci, M.; Meszaros, P.; Vietri, M.; Bradt, H.; et al. (2000). "Observation of X-ray lines from a gamma-ray burst (GRB991216): evidence of moving ejecta from the progenitor". Science. 290 (5493): 955–958. Bibcode:2000Sci...290..955P. PMID 11062121. arXiv:astro-ph/0011337

. doi:10.1126/science.290.5493.955.

. doi:10.1126/science.290.5493.955. - Weisskopf, M. C.; Hester, J. J.; Tennant, A. F.; Elsner, R. F.; Schulz, N. S.; Marshall, H. L.; Karovska, M.; Nichols, J. S.; Swartz, D. A.; et al. (2000). "Discovery of Spatial and Spectral Structure in the X-Ray Emission from the Crab Nebula". The Astrophysical Journal. 536 (2): L81–L84. Bibcode:2000ApJ...536L..81W. PMID 10859123. arXiv:astro-ph/0003216

. doi:10.1086/312733.

. doi:10.1086/312733. - Baganoff, F. K.; Bautz, M. W.; Brandt, W. N.; Chartas, G.; Feigelson, E. D.; Garmire, G. P.; Maeda, Y.; Morris, M.; Ricker, G. R.; et al. (2001). "Rapid X-ray flaring from the direction of the supermassive black hole at the Galactic Centre". Nature. 413 (6851): 45–48. Bibcode:2001Natur.413...45B. PMID 11544519. arXiv:astro-ph/0109367

. doi:10.1038/35092510.

. doi:10.1038/35092510. - Kastner, J. H.; Richmond, M.; Grosso, N.; Weintraub, D. A.; Simon, T.; Frank, A.; Hamaguchi, K.; Ozawa, H.; Henden, A. (2004). "An X-ray outburst from the rapidly accreting young star that illuminates McNeil's nebula". Nature. 430 (6998): 429–431. Bibcode:2004Natur.430..429K. PMID 15269761. arXiv:astro-ph/0408332

. doi:10.1038/nature02747.

. doi:10.1038/nature02747. - Swartz, Douglas A.; Wolk, Scott J.; Fruscione, Antonella (April 20, 2010). "Chandra's first decade of discovery". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (16): 7127–7134. PMC 2867717

. PMID 20406906. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914464107.

. PMID 20406906. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914464107.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chandra X-ray Observatory. |

- Chandra X-ray Observatory at NASA.gov

- Chandra X-ray Observatory at Harvard.edu

- Chandra podcast (2010) by Astronomy Cast