Cerro Torre

| Cerro Torre | |

|---|---|

Cerro Torre in 1987 | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 3,128 m (10,262 ft) |

| Prominence | 1,227 m (4,026 ft) [1] |

| Coordinates | 49°17′34″S 73°5′54″W / 49.29278°S 73.09833°WCoordinates: 49°17′34″S 73°5′54″W / 49.29278°S 73.09833°W |

| Geography | |

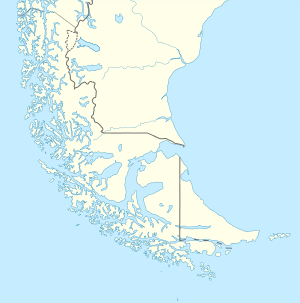

Cerro Torre Location on Southern Patagonia | |

| Location | Patagonia, Argentina, Chile[2] |

| Parent range | Andes |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 1974 by Daniele Chiappa, Mario Conti, Casimiro Ferrari and Pino Negri (Italy) |

| Easiest route | rock/snow/ice |

Cerro Torre is one of the mountains of the Southern Patagonian Ice Field in South America. It is located on the border between Argentina and Chile,[3] west of Cerro Chaltén (also known as Fitz Roy). The peak is the highest of a four mountain chain: the other peaks are Torre Egger (2,685 m (8,809 ft)),[4] Punta Herron, and Cerro Standhardt. The top of the mountain often has a mushroom of rime ice, formed by the constant strong winds, increasing the difficulty of reaching the actual summit.

First ascent

Cesare Maestri claimed in 1959 that he and Toni Egger had reached the summit and that Egger had been swept to his death by an avalanche while they were descending. Maestri declared that Egger had the camera with the pictures of the summit, but this camera was never found. Inconsistencies in Maestri's account, and the lack of bolts, pitons or fixed ropes on the route, have led most mountaineers to doubt Maestri's claim.[5] In 2005, Ermanno Salvaterra, Rolando Garibotti and Alessandro Beltrami, after many attempts by world-class alpinists, put up a confirmed route on the face that Maestri claimed to have climbed.[6][7] They did not find any evidence of previous climbing on the route described by Maestri and found the route significantly different from Maestri's description. In 2015, Rolando Garibotti published evidence that the information provided by Maestri do not agree with respect to the alleged summit ascent. Instead, he and Egger were on the western flank of Perfil de Indio.[8]

Maestri went back to Cerro Torre in 1970 with Ezio Alimonta, Daniele Angeli, Claudio Baldessarri, Carlo Claus and Pietro Vidi, trying a new route on the southeast face. With the aid of a gas-powered compressor drill, Maestri equipped 350 m of rock with bolts and got to the end of the rocky part of the mountain, just below the ice mushroom.[9] Maestri claimed that "the mushroom is not part of the mountain" and did not continue to the summit. The compressor was left, tied to the last bolts, 100 m below the top. Maestri was heavily criticised for the "unfair" methods he used to climb the mountain.

The route Maestri followed is now known as the Compressor route and was climbed to the summit in 1979 by Jim Bridwell and Steve Brewer.[10] Most parties consider the ascent complete only if they summit the often-difficult ice-rime mushroom.

The first undisputed ascent was made in 1974 by the "Ragni di Lecco" climbers Daniele Chiappa, Mario Conti, Casimiro Ferrari, and Pino Negri.[6]

Subsequent ascents

In 1977, the first Alpine style ascent was completed by Dave Carman, John Bragg and Jay Wilson (USA). They took a week to summit Cerro Torre, which had taken the Italian group two months to summit.[6] In 1980, Bill Denz (New Zealand) attempted the first solo of the Compressor Route. Over a five-month period, he made 13 concerted attempts but was driven back by storms on every occasion. On his last attempt in November 1980, he got to within 60 metres of the summit.

In January 2008, Rolando Garibotti and Colin Haley made the first complete traverse of the entire massif, climbing Aguja Standhardt, Punta Herron, Torre Egger and Cerro Torre together. They rate their route at Grade VI 5.11 A1 WI6 Mushroom Ice 6, with 2,200 m (7,200 ft) total vertical gain. This had been "one of the world's most iconic, unclimbed lines", first attempted by Ermanno Salvaterra.[11]

In 2010, Austrian Climber David Lama was held responsible for around 30 new bolts and hundreds of meters of fixed rope added to the Compressor Route on the mountain (due to bad weather conditions, much of the gear was left on the mountain and later removed by local climbers).[12][13] Although the bolts were drilled by Austrian guide, Markus Pucher,[14] and not by Lama himself, it was done as part of his trip sponsored by Red Bull and many climbers regard Lama and Red Bull as responsible. Many of the bolts were drilled next to cracks, which are usually used by climbers for protection on the route.[15] This has caused a large controversy in certain climbers' circles, as his actions are unethical according to climbing purists. Although Lama was not aware of the sheer number of bolts that were drilled, he took full responsibility for the actions. In the upcoming years, he publicly regretted what happened.[13]

On 16 January 2012, American Hayden Kennedy and Canadian Jason Kruk made the first "fair-means" (a term used to describe a reasonable use of bolts for safety and aesthetics, "a long-accepted practice in [the Patagonian] mountain range")[16] ascent of the Southeast Ridge, near the controversial Compressor Route, using only two of Maestri's original belay anchors on the headwall.[17] After summiting, Kennedy and Kruk removed 125 of the bolt-ladder bolts during their descent. Colin Haley, who watched the ascent from Norwegos, estimated the climb took them thirteen hours from their bivy on the shoulder to the summit. "The speed with which they navigated virgin ground on the upper headwall is certainly testament to Hayden's great skills on rock," Haley reported.[18] There has been much discussion concerning the removal of bolts from the compressor route by Kennedy and Kruk. However, the consensus amongst the climbing community is that of agreement for removing the bolts and has embraced their actions as having "restored Cerro Torre's southeast ridge to the realm of genuine adventure." [19]

In contrast to David Lama's free ascent (also "fair-means") (January 2012, together with Peter Ortner), Kennedy and Kruk used bolts (although not Maestri's) during their ascent.[13] Lama estimated the difficulties of his free ascent (which followed a new line circumventing the bolt traverse and in the upper headwall) as grade X- (hard 8a but mentally highly demanding; e.g., climbing on loose flakes, long runouts).[13] Lama stated that a free repetition of the original Compressor route is virtually impossible (in particular as the rock of the last pitches comprise no climbable features).

Notable ascents and attempts

- 1959 Cesare Maestri (Italy) and Toni Egger (Austria) - disputed ascent of West Face. Egger died.

- 1970 Maestri et al. (Italy), Compressor route to 60 meters below summit.[8]

- 1973 Keven Carroll (AUS) and Steven McAndrews (USA) West Face 5th ascent. Died on descent from rock fall. Earlier seen on summit ridge.

- 1974 Daniele Chiappa, Mario Conti, Casimiro Ferrari and Pino Negri (Italy). First undisputed ascent.

- 1977 Dave Carman, John Bragg and Jay Wilson (USA). First Alpine-style ascent.[6]

- 1979 Jim Bridwell and Steve Brewer complete climb of Compressor Route.

- 1985 July 3–8 First Winter Ascent by Paolo Caruso, Maurizio Giarolli and Ermanno Salvaterra (IT).[8]

- 1985 November 26 Compressor route - first solo by Marco Pedrini (Swiss).[20] Filmed by Fulvio Mariani: Cerro Torre Cumbre.

- 2004 Five Years to Paradise (ED:VI 5.10b A2 95deg, 1000m) (right center on East Face): Ermanno Salvaterra, Alessandro Beltrami, and Giacomo Rossetti (all from Italy).[21]

- 2012 January 16, First 'fair means' ascent of the Southeast Ridge (5.11 A2), without using any of Cesare Maestri's bolts on the Compressor Route, by Hayden Kennedy and Jason Kruk.[16]

- 2012 January 19, First free ascent of the Southeast Ridge by a new variation, also without using any of Cesare Maestri's bolts on the Compressor Route, by David Lama; Lama and Ortner.

- 2013 February, First free solo of Cerro Torre by Austrian alpinist Markus Pucher.[22]

In popular culture

Cerro Torre was featured in the 1991 film Scream of Stone, directed by Werner Herzog and starring Vittorio Mezzogiorno, Hans Kammerlander, and Donald Sutherland.

Jon Krakauer, aside from the detailed recounting of the climb of the mountain in his book Eiger Dreams, mentions it briefly in Into Thin Air as one of his earlier difficult ascents (1992): "I'd scaled a frightening, mile-high spike of vertical and overhanging granite called Cerro Torre; buffeted by hundred-knot winds, plastered with frangible atmospheric rime, it was once (though no longer) thought to be the world's hardest mountain".[23]

In March 2014, an adventure documentary was released following the "first ever free ascent" of Cerro Torre, featuring David Lama. Cerro Torre - A Snowball's Chance in Hell premiered at San Sebastián International Film Festival in September 2013.[24]

References

- ↑ "Cerro Torre". Peakbagger.com. this prominence value appears to be based on a summit elevation of 3,102 m.

- ↑ From Rodrigo Jordan, "Cerro Torre", in World Mountaineering, Audrey Salkeld, editor, Bulfinch Press, ISBN 0-8212-2502-2, p. 156: Cerro Torre rises "on the border between Chile and Argentina." However Chile and Argentina have long-standing border disputes.

- ↑ Congreso de la nación argentina (1998). Trámite parlamentario (in Spanish). Imprenta del Congreso de la Nación. p. 940. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

Desde la cumbre del Monte Fitz Roy la línea descenderá por la divisoria de aguas hasta un punto de coordenadas X=4.541.630 Y=1.424.600.", contained in the international treaty "Acuerdo para precisar el recorrido del límite desde el Monte Fitz Roy hasta el Cerro Daudet de 1998

- ↑ Torre Egger 2005, Huberbuam

- ↑ Garibotti, Rolando (2004). "A Mountain Unveiled". American Alpine Journal. Golden, CO, USA: American Alpine Club. 46 (78): 138–155. ISBN 0-930410-95-5.

- 1 2 3 4 Alpinist Magazine, Issue 16

- ↑ Cesare Maestri (25 September 2007). CERRO TORRE - EL ARCA DE LOS VIENTOS-1 (in Italian). YouTube. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Cerro Torre - South east ridge". pataclimb.com. 18 February 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ↑ Kearney, Alan (1993). Mountaineering in Patagonia. Seattle, Wash: The Mountaineers Books. ISBN 978-0-938567-30-1. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- ↑ climbing.com: Apocalyptic warrior Archived June 1, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Garibotti, Rolando (September 2008). "The Torre Traverse". Alpinist. Jackson, Wyoming, USA: Alpinist Magazine. 2008 (25): 52–59.

- ↑ http://www.alpinist.com/doc/web10s/newswire-david-lama-compressor-bolts

- 1 2 3 4 http://www.klettern.de/community/leute/david-lama-interview.653109.5.htm

- ↑ http://www.supertopo.com/climbers-forum/1319502/Bolts-chopped-on-Cerro-Torre

- ↑ http://www.supertopo.com/climbing/thread.php?topic_id=1319502&tn=100

- 1 2 Kennedy, Hayden; Kruk, Jason (26 January 2012). "Kennedy Kruk Release Statement". Alpinist. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ↑ "Episode 6: Hayden Kennedy: Alpine Taliban or Patagonian Custodian™? (Part 1)". The Enormocast. Retrieved 2015-11-11.

- ↑ http://www.alpinist.com/doc/web12w/newswire-compressor-kennedy-kruk-flash

- ↑ "Piolets d'Or - Special mention for two climbs on Cerro Torre". HimalayaMasala. Retrieved 2015-11-11.

- ↑ American Alpine Journal 1986, pp. 205, and 1987, pp. 103-108

- ↑ Salvaterra, Ermanno (March 2005). "Cerro Torre, Five Years to Paradise, New Route". Alpinist. Jackson, Wyoming, USA: Alpinist Magazine. 2004 (10): 82.

- ↑ "Austrian Free Solos Cerro Torre". Rock and Ice. 25 February 2013. Retrieved 2015-04-17.

- ↑ Krakauer, Jon (1999) [1997]. Into Thin Air. New York, NY, USA: Anchor Books / Random House. p. 28. ISBN 0-385-49478-5.

- ↑ http://www.cerrotorre-movie.com

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cerro Torre. |

- Andeshandbook: complete description, history, place name and routes of Cerro Torre

- Climbing topos of Cerro Torre.

- Map of Cerro Torre

- Cerro Torre on SummitPost.org

- The Guardian (UK) article on Cesare Maestri and the controversy regarding the first ascent

- IMDB article on "Scream of Stone", directed by Werner Herzog from an idea by Reinhold Messner

- AAJ 2004 article "A Mountain Unveiled: A revealing analysis of Cerro Torre's tallest tale" by Rolando Garibotti in pdf format

- Maestri article, National Geographic

- Argentines on cerro Torre

- Cuadernos Patagónicos - 3. The Cerro Torre