Ceratosaurus

| Ceratosaurus Temporal range: Late Jurassic, 153–148 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

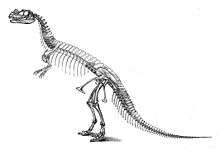

| Mounted cast of a juvenile skeleton, Dinosaur Discovery Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Ceratosauridae |

| Genus: | †Ceratosaurus Marsh, 1884 |

| Species | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Ceratosaurus /ˌsɛrətoʊˈsɔːrəs/ (from Greek κερας/κερατος, keras/keratos meaning "horn" and σαυρος/sauros meaning "lizard"), was a large predatory theropod dinosaur from the Late Jurassic Period (Kimmeridgian to Tithonian), found in the Morrison Formation of North America, and the Lourinhã Formation of Portugal (and possibly the Tendaguru Formation in Tanzania).[1] It was characterized by large jaws with blade-like teeth, a large, blade-like horn on the snout and a pair of hornlets over the eyes. The forelimbs were powerfully built but very short. The bones of the sacrum were fused (synsacrum) and the pelvic bones were fused together and to this structure[2] (i.e. similar to modern birds). A row of small osteoderms was present down the middle of the back.

Description

Ceratosaurus followed the bauplan typical for large theropod dinosaurs.[3] A biped, it moved on powerful hind legs, while its arms were reduced in size. The holotype specimen was an individual about 5.3 metres (17 ft) long; it is not clear whether this animal was fully grown.[4][5] Marsh (1884) suggested that the holotype individual weighed about half as much as Allosaurus.[6] In more recent accounts, it was estimated at 418 kilograms (922 lb), 524 kilograms (1,155 lb) and 670 kilograms (1,480 lb) by separate authors.[7] Two skeletons, assigned to the new species C. magnicornis and C. dentisulcatus by James H. Madsen and Samuel P. Welles in a 2000 monograph, were substantially larger then the holotype.[8][9] The larger of these, C. dentisuclatus, was informally estimated by Madsen to have been around 8.8 metres (29 ft) long.[10] American science writer Gregory S. Paul, in 1988, estimated the C. dentisulcatus specimen at 980 kilograms (2,160 lb).[11] A considerably lower figure, 275 kilograms (606 lb) for C. magnicornis and 452 kilograms (996 lb) for C. dentisulcatus, was proposed by John Foster in 2007.[12]

The skull was quite large in proportion to the rest of its body, measuring 62.5 cm in length in the holotype.[6][7] Its most distinctive feature was a prominent horn, which was situated on the midline of the skull behind the nostrils. Only the bony horn core is known from fossils – in the living animal, this core would have supported a keratinous sheath. In the holotype specimen, the horn core is 13 centimetres (5.1 in) long and 2 centimetres (0.79 in) wide at its base but quickly narrows down to only 1.2 centimetres (0.47 in) further up; it is 7 centimetres (2.8 in) in height. The horn core formed from co-ossified protuberances of the left and right paired nasal bones.[4] In juveniles, the halves of the horn core were not yet co-ossified.[13] In addition to the large nasal horn, Ceratosaurus possessed smaller hornlike ridges in front of each eye, similar to those of Allosaurus; these ridges were formed by the paired lacrimal bones.[12] All three horns were larger in adults than in juveniles.[13]

The upper jaws were lined with between 12 and 15 blade-like teeth on each side. The paired premaxillary bone, which formed the tip of the snout, contained merely three teeth on each half, less than in most other theropods.[5] Each half of the lower jaw was equipped with 11 to 15 teeth that were slightly straighter and less sturdy than those of the upper jaw.[9] The tooth crowns of the upper jaw were exceptionally long, measuring up to 9.3 cm in length in the largest specimen, which is equal to the minimum height of the lower jaw. In the smaller holotype specimen, the length of the upper tooth crowns (7 cm) even surpasses the minimum height of the lower jaw (6.3 cm) – in other theropods, this feature is only known from the possibly closely related Genyodectes.[14] In contrast, several members of the related Abelisauridae feature very low tooth crowns.[5]

The exact number of vertebrae is unknown due to several gaps in the holotype's spine. The sacrum consisted of 6 fused sacral vertebrae. At least 20 presacral vertebrae formed the spine of the neck and back and ca. 50 caudal vertebrae the tail. The tail comprised about half of the body's total length;[6] as in other dinosaurs, it counter-balanced the body and contained the massive caudofemoralis muscle, which was responsible for forward thrust during locomotion, pulling the upper tigh backwards when contracted. The tail of Ceratosaurus was characterized by comparatively high neural spines (upwards directed bony processes of the caudal vertebrae) and elongated chevrons (bones located below the tail vertebrae), giving the tail a deep profile in lateral view.[5] Uniquely among theropods, Ceratosaurus possessed a row of small, elongated and irregularly formed osteoderms (skin bones) running down the middle of its neck, back and most of its tail. Apart from the body midline, the skin contained additional osteoderms, as indicated by a 6 × 7 cm large plate found together with the holotype specimen; the position of this plate on the body is unknown.[4]

According to Rauhut (2000), Ceratosaurus can be distinguished based on the following features: a narrow rounded horn core centrally placed on the fused nasals, a median oval groove on nasals behind horn core, a premaxilla with three teeth, premaxillary teeth with reduced extent of mesial serrations, chevrons that are extremely long, a pubis with a large, rounded notch underneath the obturator foramen, small epaxial osteoderms.[15]

History of discovery

Ceratosaurus is known from the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry in central Utah and the Dry Mesa Quarry in Colorado. The type species, described by O. C. Marsh in 1884 and redescribed by Gilmore in 1920, is Ceratosaurus nasicornis. The first skeleton was excavated by rancher Marshall Parker Felch in 1883.

Two further species were described in 2000: C. magnicornis (from the Fruita Paleontontological Area, outside Fruita, Colorado) and C. dentisulcatus.[16] C. magnicornis has a slightly rounder horn but is otherwise highly similar to C. nasicornis; C. dentisulcatus is larger (6.7 meters), slightly more derived, and has an unknown horn shape (assuming it had them). The Portuguese remains have been ascribed to C. dentisulcatus (Mateus et al. 2000; 2006). However, the validity of C. magnicornis and C. dentisuclatus has been disputed by various palaeontologists,[17][18][19] arguing that the differences from C. nasicornis are due to individual or ontogenetic (age related) variation; thus, they would be junior synonyms of C. nasicornis. C. meriani is a nomen dubium.[20]

More additional species, including C. ingens and C. stechowi, have been described from less complete material. The former is now believed to be a dubious carcharodontosaurid instead, and the latter is a dubious ceratosaur and/or spinosaurid.[21] Ceratosaurus is present in stratigraphic zones 2 and 4-6 of the Morrison Formation.[22]

Classification

.jpg)

Relatives of Ceratosaurus include Genyodectes, Elaphrosaurus, and the abelisaurs, such as Carnotaurus. The classification of Ceratosaurus and its immediate relatives has been under intense debate. Ceratosaurs are unique in their characters; they share some primitive traits with coelophysoids, but also share some derived traits with tetanuran theropods not found in coelophysians. Its closest relatives appear to be the abelisaurs.

In the past, Ceratosaurus, the abelisaurs, and the primitive coelophysoids were all grouped together and called Ceratosauria, defined as "theropods closer to Ceratosaurus than to Aves". Recent evidence, however, has shown large distinctions between the later, larger and more advanced ceratosaurs and earlier forms like Coelophysis. While considered distant from birds among the theropods, Ceratosaurus and its kin were still very bird-like, and even had a more avian tarsus (ankle joint) than Allosaurus.

The following is a cladogram based on the phylogenetic analysis conducted by Diego Pol and Oliver W. M. Rauhut in 2012,[23] showing the relationships of Ceratosaurus:

| Ceratosauria |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

Feeding

Ceratosaurus lived alongside dinosaurs such as Allosaurus, Torvosaurus, Apatosaurus, Diplodocus, Stegosaurus and Camarasaurus. Ceratosaurus reached lengths of 6.7 m (22 ft), and weighed up to 980 kilograms (2,160 lb). It was smaller than the other large carnivores of its time (allosaurs and Torvosaurus) and likely occupied a distinctly separate niche from them. Ceratosaurus fossils are noticeably less common than those of Allosaurus, but whether this implies Ceratosaurus being rarer is uncertain (animals with certain lifestyles are more biased toward fossilization than others). Ceratosaurus had a longer, more flexible body, with a deep tail shaped like that of a crocodilian.[4] This suggests that it was a better swimmer than the stiffer Allosaurus. A recent study by Robert Bakker suggested that Ceratosaurus generally hunted aquatic prey, such as fish and crocodiles, although it had potential for feeding on large dinosaurs. The study also suggests that sometimes adults and juveniles ate together.[24] This evidence is debatable, and Ceratosaurus tooth marks are very common on large, terrestrial dinosaur prey fossils. Scavenging from corpses, smaller predators, and after larger ones also likely accounted for some of its diet.

Ceratosaurus, Allosaurus and Torvosaurus appear to have had different ecological niches, based on anatomy and the location of fossils. Ceratosaurus and Torvosaurus may have preferred to be active around waterways, and had lower, thinner bodies that would have given them an advantage in forest and underbrush terrains, whereas Allosaurus were more compact, with longer legs, faster but less maneuverable, and seem to have preferred dry floodplains.[25] Ceratosaurus, better known than Torvosaurus, differed noticeably from Allosaurus in functional anatomy by having a taller, narrower skull with large, broad teeth. Allosaurus was itself a potential food item to other carnivores, as illustrated by an Allosaurus pubic foot marked by the teeth of another theropod, probably Ceratosaurus or Torvosaurus. The location of the bone in the body (along the bottom margin of the torso and partially shielded by the legs), and the fact that it was among the most massive in the skeleton, indicates that the Allosaurus was being scavenged.[26]

Nasal horn

Marsh (1884) considered the nasal horn of Ceratosaurus to be a "most powerful weapon" for both offensive and defensive purposes, and Gilmore (1920) concurred with this analysis.[6][4] However, this interpretation is now generally considered unlikely.[10] Norman (1985) believed that the horn was "probably not for protection against other predators," but might instead have been used for intraspecific combat among male ceratosaurs contending for breeding rights.[27] Paul (1988) suggested a similar function, and illustrated two Ceratosaurus engaged in a non-lethal butting contest.[11] Rowe and Gauthier (1990) went further, suggesting that the nasal horn of Ceratosaurus was "probably used for display purposes alone" and played no role in physical confrontations.[28] If used for display, it is likely that the horn would have been brightly colored.[12]

Paleopathology

In 2001, Bruce Rothschild and others published a study examining evidence for stress fractures in theropod dinosaurs. They examined a single foot bone referred to Ceratosaurus and found that it had a stress fracture.[29]

The holotype specimen of Ceratosaurus nasicornis, USMN 4735 was found with its left metatarsals II to IV fused together. Whether or not this fusion was pathological or natural to the species became controversial when Baur in 1890 speculated that the fusion was the result of a healed fracture. An analysis by Tanke and Rothschild suggests that the fusion was indeed pathological.[30]

An unidentified species of Ceratosaurus preserved a broken tooth that showed signs of further wear received after the break.[30]

Paleoecology

The Morrison Formation is a sequence of shallow marine and alluvial sediments which, according to radiometric dating, ranges between 156.3 million years old (Ma) at its base,[31] and 146.8 million years old at the top,[32] which places it in the late Oxfordian, Kimmeridgian, and early Tithonian stages of the Late Jurassic period. This formation is interpreted as a semiarid environment with distinct wet and dry seasons. The Morrison Basin where dinosaurs lived, stretched from New Mexico to Alberta and Saskatchewan, and was formed when the precursors to the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains started pushing up to the west. The deposits from their east-facing drainage basins were carried by streams and rivers and deposited in swampy lowlands, lakes, river channels, and floodplains.[33] This formation is similar in age to the Lourinha Formation in Portugal and the Tendaguru Formation in Tanzania.[34] In 1877, this formation became the center of the Bone Wars, a fossil-collecting rivalry between early paleontologists Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope.[35]

The Morrison Formation records an environment and time dominated by gigantic sauropod dinosaurs.[36] Other dinosaurs known from the Morrison include the theropods Koparion, Stokesosaurus, Ornitholestes, Allosaurus and Torvosaurus, the sauropods Apatosaurus, Brachiosaurus, Camarasaurus, and Diplodocus, and the ornithischians Camptosaurus, Dryosaurus, Othnielia, Gargoyleosaurus and Stegosaurus.[37] Diplodocus is commonly found at the same sites as Apatosaurus, Allosaurus, Camarasaurus, and Stegosaurus.[38] Allosaurus, which accounting for 70 to 75% of theropod specimens and was at the top trophic level of the Morrison food web.[39] Many of the dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation are the same genera as those seen in Portuguese rocks of the Lourinha Formation (mainly Allosaurus, Ceratosaurus, Torvosaurus, and Stegosaurus), or have a close counterpart (Brachiosaurus and Lusotitan, Camptosaurus and Draconyx).[34] Other vertebrates that shared this paleoenvironment included ray-finned fishes, frogs, salamanders, turtles like Dorsetochelys, sphenodonts, lizards, terrestrial and aquatic crocodylomorphans such as Hoplosuchus, and several species of pterosaur like Harpactognathus and Mesadactylus. Shells of bivalves and aquatic snails are also common. The flora of the period has been revealed by fossils of green algae, fungi, mosses, horsetails, cycads, ginkgoes, and several families of conifers. Vegetation varied from river-lining forests of tree ferns, and ferns (gallery forests), to fern savannas with occasional trees such as the Araucaria-like conifer Brachyphyllum.[40]

In popular culture

Ceratosaurus has appeared in several films, including the first live action film to feature dinosaurs, D. W. Griffith's Brute Force (1914).[41] In the Rite of Spring segment of Fantasia (1940), Ceratosaurus are shown as opportunistic predators attacking Stegosaurus and sauropods trapped in mud, and was inaccurately shown without teeth. In Unknown Island (1948). In The Animal World (1956) a Ceratosaurus kills a Stegosaurus in battle, but is soon attacked by another Ceratosaurus trying to steal a meal. This scene ends with both Ceratosaurus falling to their deaths off the edge of a high cliff.

A Ceratosaurus battles a Triceratops in the 1966 remake of One Million Years B.C.. Ceratosaurus is also featured in The Land That Time Forgot (1975) where it battles a Triceratops, and its sequel The People That Time Forgot (1977) in which Patrick Wayne's character rescues a cavegirl from two pursuing Ceratosaurus by driving the dinosaurs off with smoke bombs (after having failed to frighten them off by firing shots in the air once the Ceratosaurus' attention had been shifted to Patrick Wayne's party of explorers). A Ceratosaurus made a brief appearance in the film Jurassic Park III in which it is repelled from attacking the main characters by a large mound of Spinosaurus dung. This dinosaur also appears in the television documentary When Dinosaurs Roamed America, a Ceratosaurus makes a few appearances as a predator, killing Dryosaurus and eating it, a different one is shown chasing the same Dryosaurus but is then killed and eaten by an Allosaurus. Ceratosaurus is also featured in episodes of Jurassic Fight Club where it is seen as a rival to Allosaurus and preying on Stegosaurus.

See also

References

- ↑ Mateus, O.; M.T. Antunes (2015). "Ceratosaurus sp. (Dinosauria: Theropoda) in the Late Jurassic of Portugal". 31st International Geological Congress. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- ↑ Sereno 1997

- ↑ Marsh, O.C. (1892). "Restorations of Claosaurus and Ceratosaurus". American Journal of Science. 44 (262): 343–349. doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-44.262.343.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gilmore, C.W. (1920). "Osteology of the carnivorous Dinosauria in the United States National Museum, with special reference to the genera Antrodemus (Allosaurus) and Ceratosaurus". Bulletin of the United States National Museum. 110 (110): 1–154. doi:10.5479/si.03629236.110.i.

- 1 2 3 4 Tykoski, R.S.; Rowe, T. (2004). "Ceratosauria". In Weishampel, D.B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H. The Dinosauria: Second Edition. University of California Press. pp. 47–70. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- 1 2 3 4 Marsh, O.C. (1884). "Principal characters of American Jurassic dinosaurs, part VIII: The order Theropoda" (PDF). American Journal of Science. 27 (160): 329–340. doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-27.160.329.

- 1 2 Therrien, F.; Henderson, D. M. (2007). "My theropod is bigger than yours … or not: estimating body size from skull length in theropods". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (1): 108–115.

- ↑ Tykoski and Rowe, 2004, p. 66

- 1 2 Madsen, J.H.; Welles, S.P. (2000). Ceratosaurus (Dinosauria, Theropoda): A Revised Osteology. Utah Geological Survey. pp. 1–80. ISBN 1-55791-380-3.

- 1 2 Glut, D.F. (1997). "Ceratosaurus". Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. McFarland & Company. pp. 266–270. ISBN 0-89950-917-7.

- 1 2 Paul, Gregory S. (1988). "Ceratosaurs". Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. Simon & Schuster. pp. 274–279. ISBN 0-671-61946-2.

- 1 2 3 Foster, John (2007). "Gargantuan to Minuscule: The Morrison Menagerie, Part II". Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 162–242. ISBN 0-253-34870-6.

- 1 2 Britt, B. B.; Miles, C. A.; Cloward, K. C.; Madsen, J. H. (1999). "A juvenile Ceratosaurus (Theropoda, Dinosauria) from Bone Cabin Quarry West (Upper Jurassic, Morrison Formation), Wyoming". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 19 (Supplement to No 3): 33A.

- ↑ Rauhut, O. (2004). "Provenance and anatomy of Genyodectes serus, a large-toothed ceratosaur (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from Patagonia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (4): 894–902.

- ↑ Rauhut, 2000. The interrelationships and evolution of basal theropods (Dinosauria, Saurischia). Ph.D. dissertation, Univ. Bristol [U.K.]. 440 pp.

- ↑ Madsen JH, Welles SP. Ceratosaurus (Dinosauria, Therapoda), a Revised Osteology. Miscellaneous Publication. Utah Geological Survey. ISBN 1-55791-380-3

- ↑ Britt, B. B.; Chure, D. J.; Holtz, T. R., Jr.; Miles, C. A.; Stadtman, K. L. (2000). "A reanalysis of the phylogenetic affinties of Ceratosaurus (Theropoda, Dinosauria) based on new specimens from Utah, Colorado, and Wyoming". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 20 (suppl.): 32A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2000.10010765.

- ↑ Rauhut, O. W. M. (2003). The Interrelationships and Evolution of Basal Theropod Dinosaurs. Special Papers in Palaeontology. Wiley. p. 25.

- ↑ Carrano, Matthew T.; Sampson, Scott D. (January 2008). "The Phylogeny of Ceratosauria (Dinosauria: Theropoda)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 6 (2): 192. ISSN 1477-2019. doi:10.1017/S1477201907002246.

- ↑ http://dml.cmnh.org/2000May/msg00490.html

- ↑ Rauhut, Oliver W. M. (2011). "Theropod dinosaurs from the Late Jurassic of Tendaguru (Tanzania)". Special Papers in Palaeontology. 86: 195–239. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01084.x (inactive 2017-06-07).

- ↑ Foster, J. (2007). "Appendix." Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 327-329.

- ↑ Diego Pol; Oliver W. M. Rauhut (2012). "A Middle Jurassic abelisaurid from Patagonia and the early diversification of theropod dinosaurs". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 279 (1804): 3170–5. PMC 3385738

. PMID 22628475. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.0660.

. PMID 22628475. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.0660. - ↑ Bakker RT, Bir G (2004). "Dinosaur Crime Scene Investigations". In Currie PJ, Koppelhus EB, Shugar MA, Wright JL. Feathered Dragons. Indiana University Press. pp. 301–342. ISBN 0-253-34373-9.

- ↑ Bakker, Robert T.; Bir, Gary (2004). "Dinosaur crime scene investigations: theropod behavior at Como Bluff, Wyoming, and the evolution of birdness". In Currie, Philip J.; Koppelhus, Eva B.; Shugar, Martin A.; Wright, Joanna L. Feathered Dragons: Studies on the Transition from Dinosaurs to Birds. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 301–342. ISBN 978-0-253-34373-4.

- ↑ Chure, Daniel J. (2000). "Prey bone utilization by predatory dinosaurs in the Late Jurassic of North America, with comments on prey bone use by dinosaurs throughout the Mesozoic" (PDF). Gaia. 15: 227–232. ISSN 0871-5424. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-19.

- ↑ Norman, D.B. (1985). "Carnosaurs". The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Salamander Books Ltd. pp. 62–67. ISBN 0-517-46890-5.

- ↑ Rowe, T.; Gauthier, J. (1990). "Ceratosauria". In Weishampel, D.B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H. The Dinosauria. University of California Press. pp. 151–168. ISBN 0-520-06726-6.

- ↑ Rothschild, B., Tanke, D. H., and Ford, T. L., 2001, Theropod stress fractures and tendon avulsions as a clue to activity: In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, p. 331-336.

- 1 2 Molnar, R. E., 2001, Theropod paleopathology: a literature survey: In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, p. 337-363.

- ↑ Trujillo, K.C.; Chamberlain, K.R.; Strickland, A. (2006). "Oxfordian U/Pb ages from SHRIMP analysis for the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of southeastern Wyoming with implications for biostratigraphic correlations". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 38 (6): 7.

- ↑ Bilbey, S.A. (1998). "Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry – age, stratigraphy and depositional environments". In Carpenter, K.; Chure, D.; Kirkland, J.I. The Morrison Formation: An Interdisciplinary Study. Modern Geology 22. Taylor and Francis Group. pp. 87–120. ISSN 0026-7775.

- ↑ Russell, Dale A. (1989). An Odyssey in Time: Dinosaurs of North America. Minocqua, Wisconsin: NorthWord Press. pp. 64–70. ISBN 978-1-55971-038-1.

- 1 2 Mateus, Octávio (2006). "Jurassic dinosaurs from the Morrison Formation (USA), the Lourinhã and Alcobaça Formations (Portugal), and the Tendaguru Beds (Tanzania): A comparison". In Foster, John R.; Lucas, Spencer G. Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 36. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 223–231.

- ↑ Moon, B. (2010). "The Sauropod Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic, USA): A Review". Dinosauria: 1–9.

- ↑ Foster, J. (2007). "Appendix." Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 327–329.

- ↑ Chure, Daniel J.; Litwin, Ron; Hasiotis, Stephen T.; Evanoff, Emmett; Carpenter, Kenneth (2006). "The fauna and flora of the Morrison Formation: 2006". In Foster, John R.; Lucas, Spencer G. Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 36. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 233–248.

- ↑ Dodson, Peter; Behrensmeyer, A.K.; Bakker, Robert T.; McIntosh, John S. (1980). "Taphonomy and paleoecology of the dinosaur beds of the Jurassic Morrison Formation". Paleobiology. 6 (2): 208–232.

- ↑ Foster, John R. (2003). Paleoecological Analysis of the Vertebrate Fauna of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic), Rocky Mountain Region, U.S.A. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 23. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. p. 29.

- ↑ Carpenter, Kenneth (2006). "Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus". In Foster, John R.; Lucas, Spencer G. Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 36. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 131–138.

- ↑ Glut, Donald F.; Brett-Surman, Michael K. (1997). "Dinosaurs and the media". The Complete Dinosaur. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 675–706. ISBN 0-253-33349-0.

References cited

- Tykoski, R.S.; Rowe, T. (2004). "Ceratosauria". In Weishampel, D.B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H. The Dinosauria: Second Edition. University of California Press. pp. 47–70. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.