Centrifugal force

| Classical mechanics |

|---|

|

Core topics |

In Newtonian mechanics, the centrifugal force is an inertial force (also called a "fictitious" or "pseudo" force) directed away from the axis of rotation that appears to act on all objects when viewed in a rotating frame of reference.

The concept of the centrifugal force can be applied in rotating devices, such as centrifuges, centrifugal pumps, centrifugal governors, and centrifugal clutches, and in centrifugal railways, planetary orbits and banked curves, when they are analyzed in a rotating coordinate system. The term has sometimes also been used for the reactive centrifugal force that is a reaction to a centripetal force.

Introduction

The centrifugal force is an outward force apparent in a rotating reference frame; it does not exist when a system is described relative to an inertial frame of reference.[1] All measurements of position and velocity must be made relative to some frame of reference. For example, an analysis of the motion of an object in an airliner in flight could be made relative to the airliner, to the surface of the Earth, or even to the Sun.[2] A reference frame that is at rest (or one that moves with no rotation and at constant velocity) relative to the "fixed stars" is generally taken to be an inertial frame. Any system can be analyzed in an inertial frame (and so with no centrifugal force). However, it is often more convenient to describe a rotating system by using a rotating frame--the calculations are simpler, and descriptions more intuitive. When this choice is made, fictitious forces, including the centrifugal force, arise.

In a rotating reference frame, all objects, regardless of their state of motion, appear to be under the influence of a radially (from the axis of rotation) outward force that is proportional to their mass, to the distance from the axis of rotation of the frame, and to the square of the angular velocity of the frame.[3][4] This is the centrifugal force.

Motion relative to a rotating frame results in another fictitious force: the Coriolis force. If the rate of rotation of the frame changes, a third fictitious force (the Euler force) is required. These fictitious forces are necessary for the formulation of correct equations of motion in a rotating reference frame[5][6] and allow Newton's laws to be used in their normal form in such a frame (with one exception: the fictitious forces do not obey Newton's third law: they have no equal and opposite counterparts).[5]

Examples

Turning vehicle

A common experience that gives rise to the idea of a centrifugal force is encountered by passengers riding in a vehicle, such as a car, that is changing direction. If a car is traveling at a constant speed along a straight road, then a passenger inside is not accelerating and, according to Newton's second law of motion, the net force acting on him is therefore zero (all forces acting on him cancel each other out). If the car enters a curve that bends to the left, the passenger experiences an apparent force that seems to be pulling him towards the right. This is the fictitious centrifugal force. It is needed within the passenger's local frame of reference to explain his sudden tendency to start accelerating to the right relative to the car—a tendency which he must resist by applying a rightward force to the car (for instance, a frictional force against the seat) in order to remain in a fixed position inside. Since he pushes the seat toward the right, Newton's third law says that the seat pushes him toward the left. The centrifugal force must be included in the passenger's reference frame (in which the passenger remains at rest): it counteracts the leftward force applied to the passenger by the seat, and explains why this otherwise unbalanced force does not cause him to accelerate.[7] However, it would be apparent to a stationary observer watching from an overpass above that the frictional force exerted on the passenger by the seat is not being balanced; it constitutes a net force to the left, causing the passenger to accelerate toward the inside of the curve, as he must in order to keep moving with the car rather than proceeding in a straight line as he otherwise would. Thus the "centrifugal force" he feels is the result of a "centrifugal tendency" caused by inertia.[8] Similar effects are encountered in aeroplanes and roller coasters where the magnitude of the apparent force is often reported in "G's".

A stone on a string

If a stone is whirled round on a string, in a horizontal plane, the only real force acting on the stone in the horizontal plane is applied by the string (gravity acts vertically). No other force acts on the stone so there is a net force on the stone in the horizontal plane.

In an inertial frame of reference, were it not for this net force acting on the stone, the stone would travel in a straight line, according to Newton's first law of motion. In order to keep the stone moving in a circular path, a centripetal force, in this case provided by the string, must be continuously applied to the stone. As soon as it is removed (for example if the string breaks) the stone moves in a straight line. In this inertial frame, the concept of centrifugal force is not required as all motion can be properly described using only real forces and Newton's laws of motion.

In a frame of reference rotating with the stone around the same axis as the stone, the stone is stationary. However, the force applied by the string is still acting on the stone. If one were to apply Newton's laws in their usual (inertial frame) form, one would conclude that the stone should accelerate in the direction of the net applied force--towards the axis of rotation--which it does not do. The centrifugal force and other fictitious forces must be included along with the real forces in order to apply Newton's laws of motion in the rotating frame.

Earth

The Earth, because it rotates once a day on its axis, constitutes a rotating reference frame. Because the rotation is slow, the fictitious forces it produces are small, and in everyday situations can generally be neglected. Even in calculations requiring high precision, the centrifugal force is generally not explicitly included, but rather lumped in with the gravitational force: the strength and direction of the local "gravity" at any point on the Earth's surface is actually a combination of gravitational and centrifugal forces.

Weight of an object at the poles and on the equator

If an object is weighed with a simple spring balance at one of the Earth's poles, there are two forces acting on the object: the Earth's gravity, which acts in a downward direction, and the equal and opposite tension in the spring, acting upward. There is no net force acting on the object and the spring balance so the object does not accelerate and remains stationary. The balance shows the value of the force of gravity on the object.

When the same object is weighed on the equator the same two real forces act upon the object. However, the object is moving in a circular path as the Earth rotates. When considered in an inertial frame (that is to say, one that is not rotating with the Earth), some of the force of gravity is expended just to keep the object in its circular path (centripetal force). Less tension in the spring is required to counteract the 'remaining' force of gravity. Less tension in the spring would be reflected on a scale as less weight — about 0.3% less at the equator than at the poles.[9] In the Earth reference frame (in which the object being weighed is at rest), this difference is explained by the centrifugal force.

Note: In fact, the observed weight difference is more — about 0.53%. Earth's gravity is a bit stronger at the poles than at the equator, because the Earth is not a perfect sphere, so an object at the poles is slightly closer to the center of the Earth than one at the equator; this effect combines with the centrifugal force to produce the observed weight difference.[10]

An equatorial railway

This thought experiment is more complicated than the previous examples in that it requires the use of the Coriolis force as well as the centrifugal force.

If there were a railway line running round the Earth's equator, a train moving westward along it fast enough would remain stationary in a frame moving (but not rotating) with the Earth; it would stand still as the Earth spun beneath it. In this inertial frame the situation is easy to analyze. The only forces acting on the train (assuming no wind resistance or other horizontal forces) are its gravity (downward) and the equal and opposite (upward) force from the track. There is no net force on the train and it therefore remains stationary.

In a frame rotating with the Earth the train moves in a circular orbit as it travels round the Earth. In this frame, the upward reaction force from the track and the force of gravity on the train remain the same, as they are real forces. However, in the Earth's (rotating) frame, the train is traveling in a circular path and therefore requires a centripetal (downward) force to keep it on this path. Because this uses a rotating frame, the (fictitious) centrifugal force must be applied to the train. This is equal in value to the required centripetal force but acts in an upward direction — the opposite direction to that required. It would seem that there is a net upward force on the train and it should therefore accelerate upward.

The resolution to this paradox lies in the fact that the train is in motion with respect to the rotating frame and is subject to (in addition to the centrifugal force) the Coriolis force, which, in this example, acts downward direction and is twice as strong as centrifugal force.

Derivation

For the following formalism, the rotating frame of reference is regarded as a special case of a non-inertial reference frame that is rotating relative to an inertial reference frame denoted the stationary frame.

Time derivatives in a rotating frame

In a rotating frame of reference, the time derivatives of any vector function P of time—such as the velocity and acceleration vectors of an object—will differ from its time derivatives in the stationary frame. If P1 P2, P3 are the components of P with respect to unit vectors i, j, k directed along the axes of the rotating frame,[11] then the first time derivative [dP/dt] of P with respect to the rotating frame is, by definition, dP1/dt i + dP2/dt j + dP3/dt k. If the absolute angular velocity of the rotating frame is ω then the derivative dP/dt of P with respect to the stationary frame is related to [dP/dt] by the equation:[12]

where denotes the vector cross product. In other words, the rate of change of P in the stationary frame is the sum of its apparent rate of change in the rotating frame and a rate of rotation attributable to the motion of the rotating frame. The vector ω has magnitude ω equal to the rate of rotation and is directed along the axis of rotation according to the right-hand rule.

Acceleration

Newton's law of motion for a particle of mass m written in vector form is:

where F is the vector sum of the physical forces applied to the particle and a is the absolute acceleration (that is, acceleration in an inertial frame) of the particle, given by:

where r is the position vector of the particle.

By applying the transformation above from the stationary to the rotating frame three times,[13] the absolute acceleration of the particle can be written as:

Force

The apparent acceleration in the rotating frame is [d2r/dt2]. An observer unaware of the rotation would expect this to be zero in the absence of outside forces. However, Newton's laws of motion apply only in the inertial frame and describe dynamics in terms of the absolute acceleration d2r/dt2. Therefore, the observer perceives the extra terms as contributions due to fictitious forces. These terms in the apparent acceleration are independent of mass; so it appears that each of these fictitious forces, like gravity, pulls on an object in proportion to its mass. When these forces are added, the equation of motion has the form:[14][15][16]

From the perspective of the rotating frame, the additional force terms are experienced just like the real external forces and contribute to the apparent acceleration.[17][18] The additional terms on the force side of the equation can be recognized as, reading from left to right, the Euler force , the Coriolis force , and the centrifugal force , respectively.[19] Unlike the other two fictitious forces, the centrifugal force always points radially outward from the axis of rotation of the rotating frame, with magnitude mω2r, and unlike the Coriolis force in particular, it is independent of the motion of the particle in the rotating frame. As expected, for a non-rotating inertial frame of reference the centrifugal force and all other fictitious forces disappear.[20]

Absolute rotation

Three scenarios were suggested by Newton to answer the question of whether the absolute rotation of a local frame can be detected; that is, if an observer can decide whether an observed object is rotating or if the observer is rotating.[21][22]

- The shape of the surface of water rotating in a bucket. The shape of the surface becomes concave to balance the centrifugal force against the other forces upon the liquid.

- The tension in a string joining two spheres rotating about their center of mass. The tension in the string will be proportional to the centrifugal force on each sphere as it rotates around the common center of mass.

In these scenarios, the effects attributed to centrifugal force are only observed in the local frame (the frame in which the object is stationary) if the object is undergoing absolute rotation relative to an inertial frame. By contrast, in an inertial frame, the observed effects arise as a consequence of the inertia and the known forces without the need to introduce a centrifugal force. Based on this argument, the privileged frame, wherein the laws of physics take on the simplest form, is a stationary frame in which no fictitious forces need to be invoked.

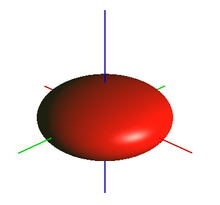

Within this view of physics, any other phenomenon that is usually attributed to centrifugal force can be used to identify absolute rotation. For example, the oblateness of a sphere of freely flowing material is often explained in terms of centrifugal force. The oblate spheroid shape reflects, following Clairaut's theorem, the balance between containment by gravitational attraction and dispersal by centrifugal force. That the Earth is itself an oblate spheroid, bulging at the equator where the radial distance and hence the centrifugal force is larger, is taken as one of the evidences for its absolute rotation.[23]

Applications

The operations of numerous common rotating mechanical systems are most easily conceptualized in terms of centrifugal force. For example:

- A centrifugal governor regulates the speed of an engine by using spinning masses that move radially, adjusting the throttle, as the engine changes speed. In the reference frame of the spinning masses, centrifugal force causes the radial movement.

- A centrifugal clutch is used in small engine-powered devices such as chain saws, go-karts and model helicopters. It allows the engine to start and idle without driving the device but automatically and smoothly engages the drive as the engine speed rises. Inertial drum brake ascenders used in rock climbing and the inertia reels used in many automobile seat belts operate on the same principle.

- Centrifugal forces can be used to generate artificial gravity, as in proposed designs for rotating space stations. The Mars Gravity Biosatellite would have studied the effects of Mars-level gravity on mice with gravity simulated in this way.

- Spin casting and centrifugal casting are production methods that uses centrifugal force to disperse liquid metal or plastic throughout the negative space of a mold.

- Centrifuges are used in science and industry to separate substances. In the reference frame spinning with the centrifuge, the centrifugal force induces a hydrostatic pressure gradient in fluid-filled tubes oriented perpendicular to the axis of rotation, giving rise to large buoyant forces which push low-density particles inward. Elements or particles denser than the fluid move outward under the influence of the centrifugal force. This is effectively Archimedes' principle as generated by centrifugal force as opposed to being generated by gravity.

- Some amusement rides make use of centrifugal forces. For instance, a Gravitron's spin forces riders against a wall and allows riders to be elevated above the machine's floor in defiance of Earth's gravity.[24]

Nevertheless, all of these systems can also be described without requiring the concept of centrifugal force, in terms of motions and forces in a stationary frame, at the cost of taking somewhat more care in the consideration of forces and motions within the system.

History of conceptions of centrifugal and centripetal forces

The conception of centrifugal force has evolved since the time of Huygens, Newton, Leibniz, and Hooke who expressed early conceptions of it. Its modern conception as a fictitious force arising in a rotating reference frame evolved in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Centrifugal force has also played a role in debates in classical mechanics about detection of absolute motion. Newton suggested two arguments to answer the question of whether absolute rotation can be detected: the rotating bucket argument, and the rotating spheres argument.[25] According to Newton, in each scenario the centrifugal force would be observed in the object's local frame (the frame where the object is stationary) only if the frame were rotating with respect to absolute space. Nearly two centuries later, Mach's principle was proposed where, instead of absolute rotation, the motion of the distant stars relative to the local inertial frame gives rise through some (hypothetical) physical law to the centrifugal force and other inertia effects. Today's view is based upon the idea of an inertial frame of reference, which privileges observers for which the laws of physics take on their simplest form, and in particular, frames that do not use centrifugal forces in their equations of motion in order to describe motions correctly.

The analogy between centrifugal force (sometimes used to create artificial gravity) and gravitational forces led to the equivalence principle of general relativity.[26][27]

Other uses of the term

While the majority of the scientific literature uses the term centrifugal force to refer to the particular fictitious force that arises in rotating frames, there are a few limited instances in the literature of the term applied to other distinct physical concepts. One of these instances occurs in Lagrangian mechanics. Lagrangian mechanics formulates mechanics in terms of generalized coordinates {qk}, which can be as simple as the usual polar coordinates or a much more extensive list of variables.[28][29] Within this formulation the motion is described in terms of generalized forces, using in place of Newton's laws the Euler–Lagrange equations. Among the generalized forces, those involving the square of the time derivatives {(dqk ⁄ dt )2} are sometimes called centrifugal forces.[30][31][32][33] In the case of motion in a central potential the Lagrangian centrifugal force has the same form as the fictitious centrifugal force derived in a co-rotating frame.[34] However, the Lagrangian use of "centrifugal force" in other, more general cases has only a limited connection to the Newtonian definition.

In another instance the term refers to the reaction force to a centripetal force, or reactive centrifugal force. A body undergoing curved motion, such as circular motion, is accelerating toward a center at any particular point in time. This centripetal acceleration is provided by a centripetal force, which is exerted on the body in curved motion by some other body. In accordance with Newton's third law of motion, the body in curved motion exerts an equal and opposite force on the other body. This reactive force is exerted by the body in curved motion on the other body that provides the centripetal force and its direction is from that other body toward the body in curved motion.[35][36] [37][38]

This reaction force is sometimes described as a centrifugal inertial reaction,[39][40] that is, a force that is centrifugally directed, which is a reactive force equal and opposite to the centripetal force that is curving the path of the mass.

The concept of the reactive centrifugal force is sometimes used in mechanics and engineering. It is sometimes referred to as just centrifugal force rather than as reactive centrifugal force[41][42] although this usage is deprecated in elementary mechanics.[43]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Centrifugal force. |

- Centrifugal mechanism of acceleration

- Equivalence principle

- Folk physics

- Lamm equation

- Lagrangian point

- Balancing of rotating masses

References

- ↑

- ↑ David P. Stern (2006). "Frames of Reference: The Basics". From Stargazers to Starships. Goddard Space Flight Center Space Physics Data Facility. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, article on Centrifuge

- ↑ Feynman Lectures on Physics, Book 1, 12-11.

- 1 2 Alexander L. Fetter; John Dirk Walecka (2003). Theoretical Mechanics of Particles and Continua. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 38–39. ISBN 0-486-43261-0.

- ↑ Jerrold E. Marsden; Tudor S. Ratiu (1999). Introduction to Mechanics and Symmetry: A Basic Exposition of Classical Mechanical Systems. Springer. p. 251. ISBN 0-387-98643-X.

- ↑ "Centrifugal force". Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 August 2016. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ↑ Knight, Judson (2016). Schlager, Neil, ed. Centripetal Force. Science of Everyday Things, Volume 2: Real-Life Physics. Thomson Learning. p. 47. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- ↑ "Curious About Astronomy?" Archived January 17, 2015, at the Wayback Machine., Cornell University, retrieved June 2007

- ↑ Boynton, Richard (2001). "Precise Measurement of Mass" (PDF). Sawe Paper No. 3147. Arlington, Texas: S.A.W.E., Inc. Retrieved 2007-01-21.

- ↑ i.e. P = P1 i + P2 j +P3 k

- ↑ John L. Synge; Byron A. Griffith (2007). Principles of Mechanics (Reprint of Second Edition of 1942 ed.). Read Books. p. 347. ISBN 1-4067-4670-3.

- ↑ Twice to and once to .

- ↑ Taylor (2005). p. 342.

- ↑ LD Landau; LM Lifshitz (1976). Mechanics (Third ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-7506-2896-9.

- ↑ Louis N. Hand; Janet D. Finch (1998). Analytical Mechanics. Cambridge University Press. p. 267. ISBN 0-521-57572-9.

- ↑ Mark P Silverman (2002). A universe of atoms, an atom in the universe (2 ed.). Springer. p. 249. ISBN 0-387-95437-6.

- ↑ Taylor (2005). p. 329.

- ↑ Cornelius Lanczos (1986). The Variational Principles of Mechanics (Reprint of Fourth Edition of 1970 ed.). Dover Publications. Chapter 4, §5. ISBN 0-486-65067-7.

- ↑ Morton Tavel (2002). Contemporary Physics and the Limits of Knowledge. Rutgers University Press. p. 93. ISBN 0-8135-3077-6.

Noninertial forces, like centrifugal and Coriolis forces, can be eliminated by jumping into a reference frame that moves with constant velocity, the frame that Newton called inertial.

- ↑ Louis N. Hand; Janet D. Finch (1998). Analytical Mechanics. Cambridge University Press. p. 324. ISBN 0-521-57572-9.

- ↑ I. Bernard Cohen; George Edwin Smith (2002). The Cambridge companion to Newton. Cambridge University Press. p. 43. ISBN 0-521-65696-6.

- ↑ Simon Newcomb (1878). Popular astronomy. Harper & Brothers. pp. 86–88.

- ↑ Myers, Rusty L. (2006). The basics of physics. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 57. ISBN 0-313-32857-9.

- ↑ An English translation is found at Isaac Newton (1934). Philosophiae naturalis principia mathematica (Andrew Motte translation of 1729, revised by Florian Cajori ed.). University of California Press. pp. 10–12.

- ↑ Barbour, Julian B. and Herbert Pfister (1995). Mach's principle: from Newton's bucket to quantum gravity. Birkhäuser. ISBN 0-8176-3823-7, p. 69.

- ↑ Eriksson, Ingrid V. (2008). Science education in the 21st century. Nova Books. ISBN 1-60021-951-9, p. 194.

- ↑ For an introduction, see for example Cornelius Lanczos (1986). The variational principles of mechanics (Reprint of 1970 University of Toronto ed.). Dover. p. 1. ISBN 0-486-65067-7.

- ↑ For a description of generalized coordinates, see Ahmed A. Shabana (2003). "Generalized coordinates and kinematic constraints". Dynamics of Multibody Systems (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 90 ff. ISBN 0-521-54411-4.

- ↑ Christian Ott (2008). Cartesian Impedance Control of Redundant and Flexible-Joint Robots. Springer. p. 23. ISBN 3-540-69253-3.

- ↑ Shuzhi S. Ge; Tong Heng Lee; Christopher John Harris (1998). Adaptive Neural Network Control of Robotic Manipulators. World Scientific. pp. 47–48. ISBN 981-02-3452-X.

In the above Euler–Lagrange equations, there are three types of terms. The first involves the second derivative of the generalized co-ordinates. The second is quadratic in where the coefficients may depend on . These are further classified into two types. Terms involving a product of the type are called centrifugal forces while those involving a product of the type for i ≠ j are called Coriolis forces. The third type is functions of only and are called gravitational forces.

- ↑ R. K. Mittal; I. J. Nagrath (2003). Robotics and Control. Tata McGraw-Hill. p. 202. ISBN 0-07-048293-4.

- ↑ T Yanao; K Takatsuka (2005). "Effects of an intrinsic metric of molecular internal space". In Mikito Toda; Tamiki Komatsuzaki; Stuart A. Rice; Tetsuro Konishi; R. Stephen Berry. Geometrical Structures Of Phase Space In Multi-dimensional Chaos: Applications to chemical reaction dynamics in complex systems. Wiley. p. 98. ISBN 0-471-71157-8.

As is evident from the first terms ..., which are proportional to the square of , a kind of "centrifugal force" arises ... We call this force "democratic centrifugal force". Of course, DCF is different from the ordinary centrifugal force, and it arises even in a system of zero angular momentum.

- ↑ See p. 5 in Donato Bini; Paolo Carini; Robert T Jantzen (1997). "The intrinsic derivative and centrifugal forces in general relativity: I. Theoretical foundations". International Journal of Modern Physics D. 6 (1).. The companion paper is Donato Bini; Paolo Carini; Robert T Jantzen (1997). "The intrinsic derivative and centrifugal forces in general relativity: II. Applications to circular orbits in some stationary axisymmetric spacetimes". International Journal of Modern Physics D. 6 (1).

- ↑ Mook, Delo E. & Thomas Vargish (1987). Inside relativity. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02520-7, p. 47.

- ↑ G. David Scott (1957). "Centrifugal Forces and Newton's Laws of Motion". 25. American Journal of Physics. p. 325.

- ↑ Signell, Peter (2002). "Acceleration and force in circular motion" Physnet. Michigan State University, "Acceleration and force in circular motion", §5b, p. 7.

- ↑ Mohanty, A. K. (2004). Fluid Mechanics. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 81-203-0894-8, p. 121.

- ↑ Roche, John (September 2001). "Introducing motion in a circle". Physics Education 43 (5), pp. 399-405, "Introducing motion in a circle". Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ Lloyd William Taylor (1959). Physics, the pioneer science. 1. Dover Publications. p. 173.

- ↑ Edward Albert Bowser (1920). An elementary treatise on analytic mechanics: with numerous examples (25th ed.). D. Van Nostrand Company. p. 357.

- ↑ Joseph A. Angelo (2007). Robotics: a reference guide to the new technology. Greenwood Press. p. 267. ISBN 1-57356-337-4.

- ↑ Eric M Rogers (1960). Physics for the Inquiring Mind. Princeton University Press. p. 302.