Central pontine myelinolysis

| Central pontine myelinolysis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Axial fat-saturated T2-weighted image showing hyperintensity in the pons with sparing of the peripheral fibers, the patient was an alcoholic admitted with a serum Na of 101 treated with hypertonic saline, he was left with quadreparesis, dysarthria, and altered mental status | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | neurology |

Central pontine myelinolysis (CPM), also known as osmotic demyelination syndrome or central pontine demyelination, is a neurological disorder caused by severe damage of the myelin sheath of nerve cells in the area of the brainstem termed the pons, predominately of iatrogenic, treatment-induced cause. It is characterized by acute paralysis, dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), and dysarthria (difficulty speaking), and other neurological symptoms.

Central pontine myelinolysis was first described by Adams et al in 1959 as a clinicopathological entity. The original paper described four cases with fatal outcomes, and the findings on autopsy. The cause was not known then but the authors suspected either a toxin or a nutritional deficiency. ‘Central pontine’ indicated the site of the lesion and ‘myelinolysis’ was used to emphasise that myelin was affected preferentially compared to the other neuronal elements. The authors intentionally avoided the term ‘demyelination’ to describe the condition, in order to differentiate this condition from multiple sclerosis and other neuroinflammatory disorders.[1]

Since this original description, demyelination in other areas of the central nervous system associated with osmotic stress has been described outside the pons.[2] The more general term "osmotic demyelination syndrome" is now preferred to the original more restrictive term "central pontine myelinolysis".[3]

Central pontine myelinolysis presents most commonly as a complication of treatment of patients with profound hyponatremia (low sodium), which can result from a varied spectrum of conditions, based on different mechanisms. It occurs as a consequence of a rapid rise in serum tonicity following treatment in individuals with chronic, severe hyponatremia who have made intracellular adaptations to the prevailing hypotonicity.[4]

Symptoms

Clinical presentation of CPM is heterogeneous and depend on the regions of the brain involved. Prior to its onset, patients may present with the neurological signs and symptoms of hyponatraemic encephalopathy such as nausea and vomiting, confusion, headache and seizures. These symptoms may resolve with normalisation of the serum sodium concentration. Three to five days later, a second phase of neurological manifestations occurs correlating with the onset of myelinolysis. Observable immediate precursors may include seizures, disturbed consciousness, gait changes, and decrease or cessation of respiratory function.[5][6]

The classical clinical presentation is the progressive development of spastic tetraparesis, pseudobulbar palsy, and emotional lability (pseudobulbar affect), with other more variable neurological features associated with brainstem damage. These result from a rapid myelinolysis of the corticobulbar and corticospinal tracts in the brainstem.[7]

Causes

The most common cause of is overly rapid correction of low blood sodium levels (hyponatremia).[8] Apart from rapid correction of hyponatraemia, there are case reports of central pontine myelinolysis in association with hypokalaemia, anorexia nervosa when feeding is started, patients undergoing dialysis and burns victims. There is a case report of central pontine myelinolysis occurring in the context of re-feeding syndrome, in the absence of hyponatremia.[1]

It has also been known to occur in patients suffering withdrawal symptoms of chronic alcoholism.[9] In these instances, occurrence may be entirely unrelated to hyponatremia or rapid correction of hyponatremia. It could affect patients who take some prescription medicines that are able to cross the blood-brain barrier and cause abnormal thirst reception - in this scenario the CPM is caused by polydipsia leading to low blood sodium levels (hyponatremia).

In schizophrenic patients with psychogenic polydipsia, inadequate thirst reception leads to excessive water intake, severely diluting serum sodium.[10] With this excessive thirst combined with psychotic symptoms, brain damage such as CPM[11] may result from hyperosmolarity caused by excess intake of fluids, (primary polydipsia) although this is difficult to determine because such patients are often institutionalised and have a long history of mental health conditions.[12]

It has been observed following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.[13]

CPM may also occur in patients prone to hyponatraemia affected by

- severe liver disease

- liver transplant[14][15][16]

- alcoholism

- severe burns[17][18]

- malnutrition

- anorexia[19][20][21]

- severe electrolyte disorders

- AIDS

- hyperemesis gravidarum[22][23]

- hyponatremia due to Peritoneal Dialysis

- Wernicke encephalopathy[24]

Pathophysiology

The currently accepted theory states that the brain cells adjust their osmolarities by changing levels of certain osmolytes like inositol, betaine, and glutamine in response to varying serum osmolality. In the context of chronic low plasma sodium (hyponatremia), the brain compensates by decreasing the levels of these osmolytes within the cells, so that they can remain relatively isotonic with their surroundings and not absorb too much fluid. The reverse is true in hypernatremia, in which the cells increase their intracellular osmolytes so as not to lose too much fluid to the extracellular space.

With correction of the hyponatremia with intravenous fluids, the extracellular tonicity increases, followed by an increase in intracellular tonicity. When the correction is too rapid, not enough time is allowed for the brain's cells to adjust to the new tonicity, namely by increasing the intracellular osmoles mentioned earlier. If the serum sodium levels rise too rapidly, the increased extracellular tonicity will continue to drive water out of the brain's cells. This can lead to cellular dysfunction and CPM.[25][26]

Diagnosis

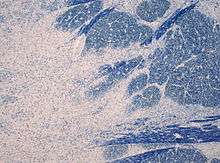

It can be diagnosed clinically in the appropriate context, but may be difficult to confirm radiologically using conventional imaging techniques. Changes are more prominent on MRI than on CT, but often take days or weeks after acute symptom onset to develop. Imaging by MRI typically demonstrates areas of hyperintensity on T2-weighted images.

Prevention and treatment

To minimise the risk of this condition developing from its most common cause, overly rapid reversal of hyponatremia, the hyponatremia should be corrected at a rate not exceeding 10 mmol/L/24 h or 0.5 mEq/L/h; or 18 m/Eq/L/48hrs; thus avoiding demyelination.[26] No large clinical trials have been performed to examine the efficacy of therapeutic re-lowering of serum sodium, or other interventions sometimes advocated such as steroids or plasma exchange.[26] Alcoholic patients should receive vitamin supplementation and a formal evaluation of their nutritional status.[27][28]

Once osmotic demyelination has begun, there is no cure or specific treatment. Care is mainly supportive. Alcoholics are usually given vitamins to correct for other deficiencies. The favourable factors contributing to the good outcome in CPM without hyponatremia were: concurrent treatment of all electrolyte disturbances, early Intensive Care Unit involvement at the advent of respiratory complications, early introduction of feeding including thiamine supplements with close monitoring of the electrolyte changes and input.[1]

Research has led to improved outcomes.[29] Animal studies suggest that inositol reduces the severity of osmotic demyelination syndrome if given before attempting to correct chronic hyponatraemia.[30] Further study is required before using inositol in humans for this purpose.

Prognosis

Though traditionally, the prognosis is considered poor, a good functional recovery is possible. All patients at risk of developing refeeding syndrome should have their electrolytes closely monitored, including sodium, potassium, magnesium, glucose and phosphate.[1] Recent data indicate that the prognosis of critically ill patients may even be better than what is generally considered,[31] despite severe initial clinical manifestations and a tendency by the intensivists to underestimate a possible favorable evolution.[32] While some patients die, most survive and of the survivors, approximately one-third recover; one-third are disabled but are able to live independently; one-third are severely disabled.[33] Permanent disabilities range from minor tremors and ataxia to signs of severe brain damage, such as spastic quadriparesis and locked-in syndrome.[34] Some improvements may be seen over the course of the first several months after the condition stabilizes.

The degree of recovery depends on the extent of the original axonal damage.[25]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Bose, P; Kunnacherry, A; Maliakal, P (19 September 2011). "Central pontine myelinolysis without hyponatraemia". The Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. 41 (3): 211–214. PMID 21949915. doi:10.4997/JRCPE.2011.305

.

. - ↑ Gocht A, Colmant HJ (1987). "Central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis: a report of 58 cases". Clin. Neuropathol. 6 (6): 262–70. PMID 3322623.

- ↑ Lampl C, Yazdi K (2002). "Central pontine myelinolysis". Eur. Neurol. 47 (1): 3–10. PMID 11803185. doi:10.1159/000047939. Archived from the original on 2010-11-18.

- ↑ Babar, S. (October 2013). "SIADH Associated With Ciprofloxacin." (PDF). Annals of Pharmacotherapy. Sage Publishing. 47 (10): 1359–1363. ISSN 1060-0280. PMID 24259701. doi:10.1177/1060028013502457. Retrieved November 18, 2013.

- ↑ Musana AK, Yale SH (August 2005). "Central pontine myelinolysis: case series and review". WMJ. 104 (6): 56–60. PMID 16218318.

- ↑ Odier C, Nguyen DK, Panisset M (July 2010). "Central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis: from epileptic and other manifestations to cognitive prognosis". J. Neurol. 257 (7): 1176–80. PMID 20148334. doi:10.1007/s00415-010-5486-7.

- ↑ Karp BI, Laureno R (November 1993). "Pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis: a neurologic disorder following rapid correction of hyponatremia". Medicine (Baltimore). 72 (6): 359–73. PMID 8231786. doi:10.1097/00005792-199311000-00001.

- ↑ Bernsen HJ, Prick MJ (September 1999). "Improvement of central pontine myelinolysis as demonstrated by repeated magnetic resonance imaging in a patient without evidence of hyponatremia". Acta Neurol Belg. 99 (3): 189–93. PMID 10544728.

- ↑ Yoon B, Shim YS, Chung SW (2008). "Central Pontine and Extrapontine Myelinolysis After Alcohol Withdrawal". Alcohol. 43 (6): 647–9. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agn050.

- ↑ Donald, Hutcheon. "Psychogenic Polydipsia (Excessive Fluid seeking Behaviour)" (PDF). American Psychological Society Divisions.

- ↑ Lim, Leslie; Krystal, Andrew (2007-06-01). "Psychotic disorder in a patient with central and extrapontine myelinolysis". Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 61 (3): 320–322. ISSN 1440-1819. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01648.x.

- ↑ Melissa, Gill,; MacDara, McCauley,; Melissa, Gill,; MacDara, McCauley, (2015-01-21). "Psychogenic Polydipsia: The Result, or Cause of, Deteriorating Psychotic Symptoms? A Case Report of the Consequences of Water Intoxication". Case Reports in Psychiatry. 2015. ISSN 2090-682X. PMC 4320790

. PMID 25688318. doi:10.1155/2015/846459.

. PMID 25688318. doi:10.1155/2015/846459. - ↑ Lim KH, Kim S, Lee YS, et al. (April 2008). "Central pontine myelinolysis in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a case report". J. Korean Med. Sci. 23 (2): 324–7. PMC 2526450

. PMID 18437020. doi:10.3346/jkms.2008.23.2.324.

. PMID 18437020. doi:10.3346/jkms.2008.23.2.324. - ↑ Singh N, Yu VL, Gayowski T (March 1994). "Central nervous system lesions in adult liver transplant recipients: clinical review with implications for management". Medicine (Baltimore). 73 (2): 110–8. PMID 8152365. doi:10.1097/00005792-199403000-00004.

- ↑ Kato T, Hattori H, Nagato M, Kiuchi T, Uemoto S, Nakahata T, Tanaka K (April 2002). "Subclinical central pontine myelinolysis following liver transplantation". Brain Dev. 24 (3): 179–82. PMID 11934516. doi:10.1016/S0387-7604(02)00013-X. Retrieved 2014-05-29.

- ↑ Martinez AJ, Estol C, Faris AA (May 1988). "Neurologic complications of liver transplantation". Neurol Clin. 6 (2): 327–48. PMID 3047544.

- ↑ McKee AC, Winkelman MD, Banker BQ (August 1988). "Central pontine myelinolysis in severely burned patients: relationship to serum hyperosmolality". Neurology. 38 (8): 1211–7. PMID 3399069. doi:10.1212/wnl.38.8.1211.

- ↑ Winkelman MD, Galloway PG (September 1992). "Central nervous system complications of thermal burns. A postmortem study of 139 patients". Medicine (Baltimore). 71 (5): 271–83. PMID 1522803. doi:10.1097/00005792-199209000-00002.

- ↑ Sugimoto T, Murata T, Omori M, Wada Y (March 2003). "Central pontine myelinolysis associated with hypokalaemia in anorexia nervosa". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 74 (3): 353–5. PMC 1738317

. PMID 12588925. doi:10.1136/jnnp.74.3.353. Retrieved 2014-05-29.

. PMID 12588925. doi:10.1136/jnnp.74.3.353. Retrieved 2014-05-29. - ↑ Keswani SC (April 2004). "Central pontine myelinolysis associated with hypokalaemia in anorexia nervosa". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 75 (4): 663; author reply 663. PMC 1739009

. PMID 15026526. Retrieved 2014-05-29.

. PMID 15026526. Retrieved 2014-05-29. - ↑ Leroy S, Gout A, Husson B, de Tournemire R, Tardieu M (June 2012). "Centropontine myelinolysis related to refeeding syndrome in an adolescent suffering from anorexia nervosa". Neuropediatrics. 43 (3): 152–4. PMID 22473289. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1307458. Retrieved 2014-05-29.

- ↑ Bergin PS, Harvey P (August 1992). "Wernicke's encephalopathy and central pontine myelinolysis associated with hyperemesis gravidarum". BMJ. 305 (6852): 517–8. PMC 1882865

. PMID 1393001. doi:10.1136/bmj.305.6852.517.

. PMID 1393001. doi:10.1136/bmj.305.6852.517. - ↑ Sutamnartpong P, Muengtaweepongsa S, Kulkantrakorn K (January 2013). "Wernicke's encephalopathy and central pontine myelinolysis in hyperemesis gravidarum". J Neurosci Rural Pract. 4 (1): 39–41. PMC 3579041

. PMID 23546346. doi:10.4103/0976-3147.105608. Retrieved 2014-05-29.

. PMID 23546346. doi:10.4103/0976-3147.105608. Retrieved 2014-05-29. - ↑ Kishimoto Y, Ikeda K, Murata K, Kawabe K, Hirayama T, Iwasaki Y (2012). "Rapid development of central pontine myelinolysis after recovery from Wernicke encephalopathy: a non-alcoholic case without hyponatremia". Intern. Med. 51 (12): 1599–603. PMID 22728498. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.51.7498. Retrieved 2014-05-29.

- 1 2 Medana IM, Esiri MM (March 2003). "Axonal damage: a key predictor of outcome in human CNS diseases". Brain. 126 (Pt 3): 515–30. PMID 12566274. doi:10.1093/brain/awg061.

- 1 2 3 Spasovski G, Vanholder R, Allolio B, Annane D, Ball S, Bichet D, Decaux G, Fenske W, Hoorn E, Ichai C, Joannidis M, Soupart A, Zietse R, Haller M, van der Veer S, Van Biesen W, Nagler E (2014). "Clinical practice guideline on diagnosis and treatment of hyponatremia". European Journal of Endocrinology. 170: G1–G47. PMID 24569125. doi:10.1530/eje-13-1020.

- ↑ Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Norenberg MD (March 1981). "Rapid correction of hyponatremia causes demyelination: relation to central pontine myelinolysis". Science. 211 (4486): 1068–70. PMID 7466381. doi:10.1126/science.7466381.

- ↑ Laureno R (1980). "Experimental pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis". Trans Am Neurol Assoc. 105: 354–8. PMID 7348981.

- ↑ Brown WD (December 2000). "Osmotic demyelination disorders: central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis". Curr. Opin. Neurol. 13 (6): 691–7. PMID 11148672. doi:10.1097/00019052-200012000-00014.

- ↑ Silver SM, Schroeder BM, Sterns RH, Rojiani AM (2006). "Myoinositol administration improves survival and reduces myelinolysis after rapid correction of chronic hyponatremia in rats". J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 65 (1): 37–44. PMID 16410747. doi:10.1097/01.jnen.0000195938.02292.39.

- ↑ Louis G, Megarbane B, Lavoué S, Lassalle V, Argaud L, Poussel JF, Georges H, Bollaert PE (March 2012). "Long-term outcome of patients hospitalized in intensive care units with central or extrapontine myelinolysis*". Critical Care Medicine. 40 (3): 970–2. PMID 22036854. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e318236f152. Retrieved 2014-05-30.

- ↑ Young GB (March 2012). "Central pontine myelinolysis: a lesson in humility*". Critical Care Medicine. 40 (3): 1026–7. PMID 22343870. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31823b8e0b. Retrieved 2014-05-30.

- ↑ Abbott R, Silber E, Felber J, Ekpo E (October 2005). "Osmotic demyelination syndrome". BMJ. 331 (7520): 829–30. PMC 1246086

. PMID 16210283. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7520.829.

. PMID 16210283. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7520.829. - ↑ Luzzio, Christopher (17 November 2015). "Central Pontine Myelinolysis". Medscape. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

External links

- MedPix Images of Osmotic Myelinolysis