Ligures

The Ligures (singular Ligus or Ligur; English: Ligurians, Greek: Λίγυες) were an ancient Indo-European people who appear to have originated in, and gave their name to, Liguria, a region of north-western Italy.[1] Elements of the Ligures appear to have migrated to other areas of western Europe, including the Iberian peninsula.

Little is known of the Old Ligurian language. It is generally believed to have been an Indo-European language with particularly strong Celtic affinities, as well as similarities to Italic languages. Only some proper names have survived, such as the inflectional suffix -asca or -asco "village".[2]

Because of the strong Celtic influences on their language and culture, they were known in antiquity as Celto-Ligurians (in Greek Κελτολίγυες Keltolígues).[3]

History

According to Plutarch, the Ligurians called themselves Ambrones, which could indicate a relationship with the Ambrones of northern Europe.[4]

Strabo tells that they were of a different race from the Celts (by which he means Gauls), who inhabited the rest of the Alps, though they resembled them in their mode of life.[5]

Aeschylus represents Hercules as contending with the Ligures on the stony plains, near the mouths of the Rhone, and Herodotus speaks of Ligures inhabiting the country above Massilia (modern Marseilles, founded by the Greeks).

Thucydides also speaks of the Ligures having expelled the Sicanians, an Iberian tribe, from the banks of the river Sicanus, in Iberia.[6]

The Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax describes the Ligyes (Ligures) as living along the Mediterranean coast from Antion (Antibes) as far as the mouth of the Rhone; then intermingled with the Iberians from the Rhone to Emporion in Spain.[7]

The Ligures seem to have been ready to engage as mercenary troops in the service of others. Ligurian auxiliaries are mentioned in the army of the Carthaginian general Hamilcar I in 480 BC.[8] Greek leaders in Sicily continued to recruit their mercenary forces from the same quarter as late as the time of Agathocles.[6][9]

The Ligures fought long and hard against the Romans, but as a result of these hostilities many were displaced from their homeland[10] and eventually assimilated into Roman culture during the 2nd century BC. Roman sources describe the Ligurians as smaller framed than the Gauls, but physically stronger, more ferocious and fiercer as warriors, hence their reputation as mercenary troops.

Lucan in his Pharsalia (c. 61 AD) described Ligurian tribes as being long-haired, and their hair a shade of auburn (a reddish-brown):

...Ligurian tribes, now shorn, in ancient daysFirst of the long-haired nations, on whose necks

Once flowed the auburn locks in pride supreme.[11]

People with Ligurian names were living south of Placentia, in Italy, as late as 102 AD.[4]

Modern theories on origins

Traditional accounts suggested that the Ligures represented the northern branch of an ethno-linguistic layer older than, and very different to, the proto-Italic peoples. It was widely believed that that a "Ligurian-Sicanian" culture occupied a wide area of southern Europe,[12] stretching from Liguria to Sicily and Iberia. However, while any such area would be broadly similar to that of the paleo-European "Tyrrhenian culture" hypothetised by later modern scholars, there are no known links between the Tyrrenians and Ligurians.

In the 19th century, the origins of the Ligures drew renewed attention from scholars. Amédée Thierry, a French historian, linked them to the Iberians,[13] while Karl Müllenhoff, professor of Germanic antiquities at the Universities of Kiel and Berlin, studying the sources of the Ora maritima by Avienus (a Latin poet who lived in the 4th century AD, but who used as a source for his own work a Phoenician Periplum of the 6th century BC),[14] held that the name 'Ligurians' generically referred to various peoples who lived in Western Europe, including the Celts, but thought the "real Ligurians" were a Pre-Indo-European population.[15]

Italian geologist and paleontologist Arturo Issel considered Ligurians as being direct descendants of the Cro-Magnon men which lived throughout Gaul from the Mesolithic period.[16]

Dominique-François-Louis Roget, Baron de Belloguet, claimed a "Gallic" origin of the Ligurians.[17] During the Iron Age the spoken language, the main divinities and the workmanship of the artifacts unearthed in the area of Liguria (such as the numerous torcs found) were similar to those of Celtic culture in both style and type.[18]

Those in favor of an Indo-European origin included Henri d'Arbois de Jubainville, a 19th-century French historian, who argued the Ligurians were the earliest Indo-European speakers of the Western Europe. Jubainville's "Celto-Ligurian hypothesis", as it latter became known, was significantly expanded in the second edition of his initial study. It inspired a body of contemporary philological research, as well as some archaeological work. The Celto-Ligurian hypothesis became associated with the Funnelbeaker culture and "expanded to cover much of Central Europe".[19]

Julius Pokorny adapted the Celto-Ligurian hypothesis into one linking the Ligures to the Illyrians, citing an array of similar evidence from Eastern Europe. Under this theory the "Ligures-Illyrians" became associated with the prehistoric Urnfield peoples.[20]

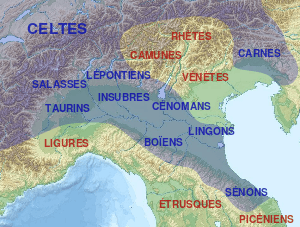

Tribes

Numerous tribes of Ligures are mentioned by ancient historians, among them:

- Alpini (or Montani) (in the hinterland of Savona)

- Apuani (in Lunigiana)

- Bimbelli

- Bagienni (or Vagienni) (in the area of Bene Vagienna)

- Briniates (or Boactes) (in the area of Brugnato)

- Celelates

- Cerdiciates

- Commoni

- Cosmonates (in the area of Castellazzo Bormida)

- Deciates (in modern Provence, west of the river Var)

- Elisyces/Helisyces - a tribe that dwelt in the region of Narbo (Narbonne) and modern northern Roussillon. May have been either Iberian or Ligurian or a Ligurian-Iberian tribe.

- Epanterii

- Euburiates

- Friniates (in the area now called Frignano)

- Garuli

- Genuates (or Genuenses) (in and around Genoa)

- Hercates

- Ilvates (or Iluates) (if different from the Iriates) (on the island of Elba)

- Iriates (or Ilvates, Iluates?) (in the territory of Tortona, Voghera and Libarna)

- Ingauni

- Intemelii

- Langates (or Langenses) (north of the Genuates)

- Lapicini (or Lapicinii)

- Laevi (along the Ticino River and in the area of Pavia)

- Libici (or Libui)

- Magelli (or Mucelli) (in the Mugello region)

- Marici (near the confluence of the rivers Orba, Bormida and Tanaro)

- Olivari

- Oxybii (or Oxibii) (in modern Provence)

- Sabates (in the area of Vado Ligure)

- Salassi (Gallo-Ligurian people) (in and around Aosta Valley)

- Salluvii (or Saluvii) (if different from the Salyes) (in modern Provence)

- Salyes (or Salii, or also Salluvii, Saluvii?) (in modern Provence)

- Statielli (or Statiellates) (in the valleys of the Orba [left bank], Bormida and Tanaro)

- Sueltri (or Suelteri)

- Taurini (or Taurisci) (Gallo-Ligurian people) (in Turin region)

- Tigulli (or Tigullii)

- Tricastini

- Vediantii

- Veiturii (west of the Genuates, in and around Voltri [now a suburb of Genoa])

- Veleiates (or Veliates) (between Veleia and Libarna)

- Veneni

In the island of Corsica and far northeast Sardinia dwelt a group of tribes called Corsi, although they are classified as nuragic tribes (that may have been related to the Iberians, the Aquitanians or to the Etruscans) they also may have been a group of ligurian tribes, like the Ilvates in the neighboring Ilva (Elba) island (nuragic tribes, in Corsica and Sardinia, were not necessarily from the same ethnic origin or spoke the same language):

- Corsi

- Belatones (Belatoni)

- Cervini

- Cilebenses (Cilibensi)

- Corsi Proper, they dwelt at the extreme north-east of Sardinia, near the Tibulati and immediately north of the Coracenses.

- Cumanenses (Cumanesi)

- Lestricones/Lestrigones (Lestriconi/Lestrigoni)

- Licinini

- Longonenses (Longonensi)

- Macrini

- Opini

- Subasani

- Sumbri

- Tarabeni

- Tibulati, they dwelt at the extreme north of Sardinia, about the ancient city of Tibula, near the Corsi (for whom Corsica is named) and immediately north of the Coracenses.

- Titiani

- Venacini

See also

References

- ↑ "Liguria", in William Smith (ed.), Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography (1854)

- ↑ The suffixes -asca or -asco do not appear to be related to the Celtic -brac, possibly meaning "swamp".

- ↑ Baldi, Philip (2002). The Foundations of Latin. Walter de Gruyter. p. 112.

- 1 2 Boardman, John (1988). The Cambridge ancient history: Persia, Greece and the Western Mediterranean c. 525–479 BC. p. 716.

- ↑ Strabo, Geography, book 2, chapter 5, section 28.

- 1 2 William Smith, ed. (1854). "Liguria". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography.

- ↑ Shipley, Graham (2008). "The Periplous of Pseudo-Scylax: An Interim Translation".

- ↑ Herodotus 7.165; Diodorus Siculus 11.1.

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus 21.3.

- ↑ Broadhead, William (2002). Internal migration and the transformation of Republican Italy (PDF) (Ph.D.). University College London. p. 15.

- ↑ Lucan, Pharsalia, I. 496, translated by Edward Ridley (1896).

- ↑ Sciarretta, Antonio (2010). Toponomastica d'Italia. Nomi di luoghi, storie di popoli antichi. Milano: Mursia. pp. 174–194. ISBN 978-88-425-4017-5.

- ↑ Amédée Thierry, Histoire des Gaulois depuis les temps les plus reculés.

- ↑ Postumius Rufius Festus (qui et) Avienius, Ora maritima, 129–133 (nel quale in modo oscuro indica i Liguri come abitanti a nord delle "isole oestrymniche"; 205 (Liguri a nord della città di Ophiussa nella penisola iberica); 284–285 (il fiume Tartesso nascerebbe dalle "paludi ligustine").

- ↑ Karl Viktor Müllenhoff, Deutsche Alterthurnskunde, I volume.

- ↑ Arturo Issel Liguria geologica e preistorica, Genoa 1892, II volume, pp. 356–357.

- ↑ Dominique François Louis Roget de Belloguet, Ethnogénie gauloise, ou Mémoires critiques sur l'origine et la parenté des Cimmériens, des Cimbres, des Ombres, des Belges, des Ligures et des anciens Celtes. Troisiéme partie. Preuves intellectuelles. Le génie gaulois, Paris 1868.

- ↑ Gilberto Oneto Paesaggio e architettura delle regioni padano-alpine dalle origini alla fine del primo millennio, Priuli e Verlucc, editori 2002, pp. 34–36, 49.

- ↑ See, in particular McEvedy 1967:29ff.

- ↑ Henning, Andersen (2003). Language Contacts in Prehistory: Studies in Stratigraphy. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 16–17.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ligures. |

- ARSLAN E. A. 2004b, LVI.14 Garlasco, in I Liguri. Un antico popolo europeo tra Alpi e Mediterraneo, Catalogo della Mostra (Genova, 23.10.2004-23.1.2005), Milano-Ginevra, pp. 429–431.

- ARSLAN E. A. 2004 c.s., Liguri e Galli in Lomellina, in I Liguri. Un antico popolo europeo tra Alpi e Mediterraneo, Saggi Mostra (Genova, 23.10.2004–23.1.2005).

- Raffaele De Marinis, Giuseppina Spadea (a cura di), Ancora sui Liguri. Un antico popolo europeo tra Alpi e Mediterraneo, De Ferrari editore, Genova 2007 (scheda sul volume).

- John Patterson, Sanniti,Liguri e Romani,Comune di Circello;Benevento

- Giuseppina Spadea (a cura di), I Liguri. Un antico popolo europeo tra Alpi e Mediterraneo" (catalogo mostra, Genova 2004–2005), Skira editore, Genova 2004