Pholcus phalangioides

| Pholcus phalangioides | |

|---|---|

| |

| With cranefly prey | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Arachnida |

| Order: | Araneae |

| Suborder: | Araneomorphae |

| Family: | Pholcidae |

| Genus: | Pholcus |

| Species: | P. phalangioides |

| Binomial name | |

| Pholcus phalangioides Füssli, 1775 | |

| |

Pholcus phalangioides, known as the longbodied cellar spider or the skull spider due to its cephalothorax looking like a human skull, is a spider of the family Pholcidae. Females have a body length of about 9 mm; males are slightly smaller. Its legs are about 5 or 6 times the length of its body (reaching up to 7 cm of leg span in females). Its habit of living on the ceilings of rooms, caves, garages or cellars gives rise to one of its common names. They are considered beneficial in some parts of the world because they kill and eat other spiders, including species that can be considered a problem to humans such as hobo and redback spiders.[1][2]

This is the only spider species described by the Swiss entomologist Johann Kaspar Füssli, who first recorded it for science in 1775.[3] Confusion often arises over its common name, because "daddy long-legs" is also applied to two other distantly related arthropods: one being Opiliones, another order of arachnid known also as a "harvestman", the other an insect less ambiguously called the crane fly.

Habitat

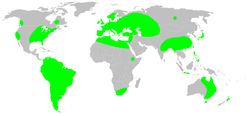

Originally a species restricted to warmer parts of the west Palearctic,[4] through the help of humans this synanthrope now occurs throughout a large part of the world.[1] It is unable to survive in cold weather, and consequently it is restricted to (heated) houses in some parts of its range.

Behaviour

Pholcus phalangioides is not considered aggressive, its first line of defense being to shake its web violently when disturbed as a mechanism against predators. It can easily catch and eat other spiders (even those much larger than itself, such as Eratigena atrica), mosquitoes and other insects, and woodlice. When food is scarce, it will prey on its own kind. Rough handling will cause some of its legs to become detached.

Peak breeding in this species occurs between June and September.[5] The female holds the 20 to 30 eggs in her pedipalps.[5] Spiderlings are transparent with short legs, and change their skin about 5 or 6 times as they mature.

Venom

An urban legend states that Pholcidae are the most venomous spiders in the world but that it is nevertheless harmless to humans because its fangs cannot penetrate human skin. Both of these claims have been proven untrue. Recent research has shown that pholcid venom has a relatively weak effect on insects.[6] In the MythBusters episode "Daddy Long-Legs" it was shown that the spider's fangs (0.25 mm) could penetrate human skin (0.1 mm), but that only a very mild burning feeling was felt for a few seconds.[7]

Gallery

Male with prey

Male with prey Cellar spider carrying its spiderlings

Cellar spider carrying its spiderlings Female with egg sac

Female with egg sac Female with offspring

Female with offspring- in Oxfordshire

- Cellar Spider with Green Lacewing

Web

Web

References

- 1 2 Daddy Long Legs – Queensland Museum

- ↑ FAMILY PHOLCIDAE – Daddy long-leg Spiders

- ↑ "The Nearctic Spider Database: Pholcus phalangioides (Fuesslin, 1775) Description". canadianarachnology.org. Archived from the original on 2009-11-06. Retrieved 2016-08-28.

- ↑ Adams, Richard J. (2014-01-28). "Field Guide to the Spiders of California and the Pacific Coast States". p. 73. Retrieved 2016-09-08.

- 1 2 Ferrick, A. (2002). "ADW: Pholcus phalangioides: INFORMATION". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2016-08-28.

- ↑ Spider Myths – If it could only bite

- ↑ "Buried in Concrete, Daddy Long-legs, Jet Taxi". MythBusters. Season 2004. Episode 13. 25 February 2004. Discovery Channel. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pholcus phalangioides. |

- Information on the Long Bodied Cellar Spider – often called "daddy long legs"

- Description and pictures

- Long description and pictures

- The checklist of Lithuanian spiders (Arachnida: Araneae). Marija Biteniekytė and Vygandas Rėlys, Biologija, 2011, Vol. 57, No. 4, pages 148–158, doi:10.6001/biologija.v57i4.1926