Diclofenac

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | , Cataflam, Voltaren, see trade names[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a689002 |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | oral, rectal, intramuscular, intravenous (renal- and gallstones), topical |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | More than 99% |

| Metabolism | hepatic, oxidative, primarily by CYP2C9, also by CYP2C8, CYP3A4, as well as conjugative by glucuronidation (UGT2B7) and sulfation;[2] no active metabolites exist |

| Biological half-life | 1.2-2 hr (35% of the drug enters enterohepatic recirculation) |

| Excretion | 40% biliary 60% urine |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.035.755 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C14H11Cl2NO2 |

| Molar mass | 296.148 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Diclofenac (sold under a number of trade names)[1] is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) taken or applied to reduce inflammation and as an analgesic reducing pain in certain conditions. It is supplied as or contained in medications under a variety of trade names.

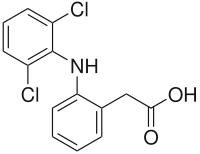

The name "diclofenac" derives from its chemical name: 2-(2,6-dichloranilino) phenylacetic acid. Diclofenac was first synthesized by Alfred Sallmann and Rudolf Pfister and introduced as Voltaren by Ciba-Geigy (now Novartis) in 1973.[3]

In the United Kingdom, United States, India, and Brazil diclofenac may be supplied as either the sodium or potassium salt; in China, it is most often supplied as the sodium salt, while in some other countries it is only available as the potassium salt. It is available as a generic drug in a number of formulations, including diclofenac diethylamine, which is applied topically. Over-the-counter (OTC) use is approved in some countries for minor aches and pains and fever associated with common infections. As of 2015 the cost for a typical month of medication in the United States is 50 to 100 USD.[4]

The drug's use in animals is controversial due to its toxicity which can rapidly kill scavenging birds that eat dead animals. It has been banned for veterinary use in many countries.

Medical uses

Diclofenac is used to treat pain, inflammatory disorders, and dysmenorrhea.[5]

Pain

Inflammatory disorders may include musculoskeletal complaints, especially arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, polymyositis, dermatomyositis, osteoarthritis, dental pain, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) pain, spondylarthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, gout attacks,[6] and pain management in cases of kidney stones and gallstones. An additional indication is the treatment of acute migraines.[7] Diclofenac is used commonly to treat mild to moderate postoperative or post-traumatic pain, in particular when inflammation is also present,[6] and is effective against menstrual pain and endometriosis.

Diclofenac is also available in topical forms and has been found to be useful for osteoarthritis but not other types of long-term musculoskeletal pain.[8]

It may also help with actinic keratosis, and acute pain caused by minor strains, sprains, and contusions (bruises).[9]

In many countries,[10] eye drops are sold to treat acute and chronic nonbacterial inflammation of the anterior part of the eyes (e.g., postoperative states). Diclofenac eye drops have also been used to manage pain for traumatic corneal abrasion.[11]

Diclofenac is often used to treat chronic pain associated with cancer, in particular if inflammation is also present (Step I of the World Health Organization (WHO) scheme for treatment of chronic pain).[12] Diclofenac can be combined with opioids if needed such as a fixed combination of diclofenac and codeine.

Other

Diclofenac has been found to increase the blood pressure in patients with Shy–Drager syndrome and diabetes mellitus. Currently, this use is highly investigative and cannot be recommended as routine treatment.

Voltaren (diclofenac) 50 mg enteric coated tablets

Voltaren (diclofenac) 50 mg enteric coated tablets- Arthrotec (diclofenac and misoprostol) 50-mg tablets

Sintofarm (diclofenac) for suppository administration

Sintofarm (diclofenac) for suppository administration

Contraindications

- Hypersensitivity against diclofenac

- History of allergic reactions (bronchospasm, shock, rhinitis, urticaria) following the use of other NSAIDs such as aspirin

- Third-trimester pregnancy

- Active stomach and/or duodenal ulceration or gastrointestinal bleeding

- Inflammatory bowel disease such as Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis

- Severe insufficiency of the heart (NYHA III/IV)

- Pain management in the setting of coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery

- Severe liver insufficiency (Child-Pugh Class C)

- Severe renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance <30 ml/min)

- Caution in patients with pre-existing hepatic porphyria, as diclofenac may trigger attacks

- Caution in patients with severe, active bleeding such as cerebral hemorrhage

- NSAIDs in general should be avoided during dengue fever, as it induces (often severe) capillary leakage and subsequent heart failure.

- Caution in patients with fluid retention or heart failure.

- Can lead to onset of new hypertension or worsening of pre-existing hypertension

- Can cause serious skin adverse events such as exfoliative dermatitis, Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS), and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), which can be fatal.[2]

Side effects

Diclofenac consumption has been associated with significantly increased vascular and coronary risk in a study including coxib, diclofenac, ibuprofen and naproxen.[13] Upper gastrointestinal complications were also reported.[13] Major vascular events were increased by about a third by diclofenac, chiefly due to an increase in major coronary events.[13] Compared with placebo, of 1000 patients allocated to diclofenac for a year, three more had major vascular events, one of which was fatal.[13] Vascular death was increased significantly by diclofenac.[13]

Cardiac

In 2013, a study funded by core grants from the UK Medical Research Council and the British Heart Foundations, and collaboration coordinated by the Clinical Trial Service Unit & Epidemiological Studies Unit (CTSU) at the University of Oxford, UK; major vascular events were increased by about a third by diclofenac (rate ratio 1·41,95% CI 1·12–1·78; p=0·0036), chiefly due to an increase in major coronary events (1·70, 1·19–2·41; p=0·0032).[13] Compared with placebo, of 1000 patients allocated to diclofenac for a year, three more had major vascular events, one of which was fatal.[13] Vascular death was increased significantly by diclofenac (1·65, 0·95–2·85, p=0·0187).[13]

Following the identification of increased risks of heart attacks with the selective COX-2 inhibitor rofecoxib in 2004, attention has focused on all the other members of the NSAIDs group, including diclofenac. Research results are mixed, with a meta-analysis of papers and reports up to April 2006 suggesting a relative increased rate of heart disease of 1.63 compared to nonusers.[14] Professor Peter Weissberg, Medical Director of the British Heart Foundation said, "However, the increased risk is small, and many patients with chronic debilitating pain may well feel that this small risk is worth taking to relieve their symptoms". Only aspirin was found not to increase the risk of heart disease; however, this is known to have a higher rate of gastric ulceration than diclofenac.

A subsequent large study of 74,838 users of NSAIDs or coxibs found no additional cardiovascular risk from diclofenac use.[15] A very large study of 1,028,437 Danish users of various NSAIDs or coxibs found the "Use of the nonselective NSAID diclofenac and the selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor rofecoxib was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular death (odds ratio, 1.91; 95% confidence interval, 1.62 to 2.42; and odds ratio, 1.66; 95% confidence interval, 1.06 to 2.59, respectively), with a dose-dependent increase in risk."[16] In Britain the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) said in June 2013 that the drug should not be used by people with serious underlying heart conditions—people who had suffered heart failure, heart disease or a stroke were advised to stop using it completely.[17] As of January 15 2015 the MHRA announced that diclofenac will be reclassified as a prescription-only medicine (POM) due to the risk of cardiovascular adverse events.[18]

Diclofenac is similar in COX-2 selectivity to celecoxib.[19] A review by FDA Medical Officer David Graham concluded diclofenac does increase the risk of myocardial infarction.[20]

Gastrointestinal

- Gastrointestinal complaints are most often noted. The development of ulceration and/or bleeding requires immediate termination of treatment with diclofenac. Most patients receive a gastro-protective drug as prophylaxis during long-term treatment (misoprostol, ranitidine 150 mg at bedtime or omeprazole 20 mg at bedtime).

Hepatic

- Liver damage occurs infrequently, and is usually reversible. Hepatitis may occur rarely without any warning symptoms and may be fatal. Patients with osteoarthritis more often develop symptomatic liver disease than patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Liver function should be monitored regularly during long-term treatment. If used for the short-term treatment of pain or fever, diclofenac has not been found more hepatotoxic than other NSAIDs.

- As of December 2009, Endo, Novartis, and the US FDA notified healthcare professionals to add new warnings and precautions about the potential for elevation in liver function tests during treatment with all products containing diclofenac sodium.[21]

- Cases of drug-induced hepatotoxicity have been reported in the first month, but can occur at any time during treatment with diclofenac. Postmarketing surveillance has reported cases of severe hepatic reactions, including liver necrosis, jaundice, fulminant hepatitis with and without jaundice, and liver failure. Some of these reported cases resulted in fatalities or liver transplantation.

- Physicians should measure transaminases periodically in patients receiving long-term therapy with diclofenac. Based on clinical trial data and postmarketing experiences, transaminases should be monitored within 4 to 8 week after initiating treatment with diclofenac.

Renal

- NSAIDs "are associated with adverse renal [kidney] effects caused by the reduction in synthesis of renal prostaglandins"[22] in sensitive persons or animal species, and potentially during long-term use in nonsensitive persons if resistance to side effects decreases with age. However, this side effect cannot be avoided merely by using a COX-2 selective inhibitor because, "Both isoforms of COX, COX-1 and COX-2, are expressed in the kidney... Consequently, the same precautions regarding renal risk that are followed for nonselective NSAIDs should be used when selective COX-2 inhibitors are administered."[22] However, diclofenac appears to have a different mechanism of renal toxicity.

- Studies in Pakistan showed diclofenac caused acute kidney failure in vultures when they ate the carcasses of animals that had recently been treated with it. Drug-sensitive species and individual humans are initially assumed to lack genes expressing specific drug detoxification enzymes.[23]

Mental health

- Mental health side effects have been reported. These symptoms are rare, but exist in significant enough numbers to include as potential side effects. These include depression, anxiety, irritability, nightmares, and psychotic reactions.[24]

Other

- Diclofenac and other NSAIDs can cause temporary infertility in women,[25] particularly those who take it regularly. NSAIDs have been known to cause luteinized unruptured follicle syndrome, which delays or prevents ovulation.[26]

- Bone marrow depression is noted infrequently (leukopenia, agranulocytosis, thrombopenia with/without purpura, aplastic anemia). These conditions may be life-threatening and/or irreversible, if detected too late. All patients should be monitored closely. Diclofenac is a weak and reversible inhibitor of thrombocytic aggregation needed for normal coagulation.

- It induces warm antibody hemolytic anemia by inducing antibodies to Rh antigens; ibuprofen also does this.[27]

- Diclofenac may disrupt the normal menstrual cycle.

- Research (published 2010) has linked use of diclofenac to an increased risk of stroke.[28]

- Research (published 2014) has been reported by Pongkorpsakol and co-workers, Diclofenac may be useful to treat diarrhea. </ref>

Mechanism of action

The primary mechanism responsible for its anti-inflammatory, antipyretic, and analgesic action is thought to be inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis by inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX). It also appears to exhibit bacteriostatic activity by inhibiting bacterial DNA synthesis.[29]

Inhibition of COX also decreases prostaglandins in the epithelium of the stomach, making it more sensitive to corrosion by gastric acid. This is also the main side effect of diclofenac. Diclofenac has a low to moderate preference to block the COX2-isoenzyme (approximately 10-fold) and is said to have, therefore, a somewhat lower incidence of gastrointestinal complaints than noted with indomethacin and aspirin.

The action of one single dose is much longer (6 to 8 hr) than the very short half-life of the drug indicates. This could be partly because it persists for over 11 hours in synovial fluids.[30]

Diclofenac may also be a unique member of the NSAIDs. Some evidence indicates it inhibits the lipoxygenase pathways, thus reducing formation of the leukotrienes (also pro-inflammatory autacoids). It also may inhibit phospholipase A2 as part of its mechanism of action. These additional actions may explain its high potency - it is the most potent NSAID on a broad basis.[31]

Marked differences exist among NSAIDs in their selective inhibition of the two subtypes of cyclooxygenase, COX-1 and COX-2. Much pharmaceutical drug design has attempted to focus on selective COX-2 inhibition as a way to minimize the gastrointestinal side effects of NSAIDs such as aspirin. In practice, use of some COX-2 inhibitors with their adverse effects has led to massive numbers of patient family lawsuits alleging wrongful death by heart attack, yet other significantly COX-selective NSAIDs, such as diclofenac, have been well tolerated by most of the population.

Besides the COX-inhibition, a number of other molecular targets of diclofenac possibly contributing to its pain-relieving actions have recently been identified. These include:

- Blockage of voltage-dependent sodium channels (after activation of the channel, diclofenac inhibits its reactivation also known as phase inhibition)

- Blockage of acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs)[32]

- Positive allosteric modulation of KCNQ- and BK-potassium channels (diclofenac opens these channels, leading to hyperpolarization of the cell membrane)

Ecological effects

Use of diclofenac in animals has been reported to have led to a sharp decline in the vulture population in the Indian subcontinent – a 95% decline by 2003[33] and a 99.9% decline by 2008. The mechanism is presumed to be renal failure,[34] however toxicity may be due to direct inhibition of uric acid secretion in vultures.[35] Vultures eat the carcasses of livestock that have been administered veterinary diclofenac, and are poisoned by the accumulated chemical,[36] as vultures do not have a particular enzyme to break down diclofenac. At a meeting of the National Wildlife Board in March 2005, the Government of India announced it intended to phase out the veterinary use of diclofenac.[37] Meloxicam is a safer candidate to replace use of diclofenac.[38] It is more expensive than diclofenac, but the price is coming down as more drug companies begin to manufacture it.[39]

Steppe eagles have same vulnerability to [40]diclofenac as vultures and may also fall victim to it.[41] Diclofenac has been shown also to harm freshwater fish species such as rainbow trout.[42][43][44][45] In contrast, New World vultures, such as the turkey vulture, can tolerate at least 100 times the level of diclofenac that is lethal to Gyps species.[46]

"The loss of tens of millions of vultures over the last decade has had major ecological consequences across the Indian Subcontinent that pose a potential threat to human health. In many places, populations of feral dogs (Canis familiaris) have increased sharply from the disappearance of Gyps vultures as the main scavenger of wild and domestic ungulate carcasses. Associated with the rise in dog numbers is an increased risk of rabies"[38] and casualties of almost 50,000 people.[47] The Government of India cites this as one of those major consequences of a vulture species extinction.[37] A major shift in transfer of corpse pathogens from vultures to feral dogs and rats could lead to a disease pandemic causing millions of deaths in a crowded country like India; whereas vultures’ digestive systems safely destroy many species of such pathogens.

The loss of vultures has had a social impact on the Indian Zoroastrian Parsi community, who traditionally use vultures to dispose of human corpses in Towers of Silence, but are now compelled to seek alternative methods of disposal.[38]

Despite the vulture crisis, diclofenac remains available in other countries including many in Europe.[48] It was controversially approved for veterinary use in Spain in 2013 and continues to be available, despite Spain being home to around 90% of the European vulture population and an independent simulation showing that the drug could reduce the population of vultures by 1-8% annually. Spain's medicine agency presented simulations suggesting that the number of deaths would be quite small.[49][50]

Formulations and trade names

Pennsaid is a minimally systemic prescription topical lotion formulation of 1.5% w/w diclofenac sodium, which is approved in the US, Canada and other countries for osteoarthritis of the knee.

Flector Patch, a minimally systemic topical patch formulation of diclofenac, is indicated for acute pain due to minor sprains, strains, and contusions. The patch has been approved in many other countries outside the US under different brand names.

Voltaren and Voltarol contain the sodium salt of diclofenac. In the United Kingdom, Voltarol can be supplied with either the sodium salt or the potassium salt, while Cataflam, sold in some other countries, is the potassium salt only. However, Voltarol Emulgel contains diclofenac diethylammonium, in which a 1.16% concentration is equivalent to a 1% concentration of the sodium salt. In 2016 Voltarol was one of the biggest selling branded over-the-counter medications sold in Great Britain, with sales of £39.3 million.[51]

Diclofenac is available in stomach acid-resistant formulations (25 and 50 mg), fast-disintegrating oral formulations (25 and 50 mg), powder for oral solution (50 mg), slow- and controlled-release forms (75, 100 or 150 mg), suppositories (50 and 100 mg), and injectable forms (50 and 75 mg).

Diclofenac is also available over-the-counter in some countries: 12.5 mg diclofenac as potassium salt in Switzerland (Voltaren dolo), the Netherlands (Voltaren K), and preparations containing 25 mg diclofenac as the potassium salt in Germany (various trade names), New Zealand, Australia, Japan, (Voltaren Rapid), and Sweden (Voltaren T and Diclofenac T). Diclofenac as potassium salt can be found throughout the Middle East in 25-mg and 50-mg doses (Cataflam). Solaraze (3% diclofenac sodium gel) is topically applied, twice a day for three months, to manage the skin condition known as actinic or solar keratosis. Parazone-DP is combination of diclofenac potassium and paracetamol, manufactured and supplied by Ozone Pharmaceuticals and Chemicals, Gujarat,India.

On 14 January 2015, diclofenac oral preparations were reclassified as prescription-only medicines in the UK. The topical preparations are still available without prescription.[52]

Diclofenac formulations are available worldwide under many different trade names.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 Drugs.com Diclofenac international availability

- 1 2 "Diclofenac Potassium". Drugs.com. Drugsite Trust. Retrieved 2015-11-15.

- ↑ Altman R, Bosch B, Brune K, Patrignani P, Young C (2015). "Advances in NSAID development: evolution of diclofenac products using pharmaceutical technology". Drugs. 75: 859–77. PMC 4445819

. PMID 25963327. doi:10.1007/s40265-015-0392-z.

. PMID 25963327. doi:10.1007/s40265-015-0392-z. - ↑ Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 7. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ↑ "Diclofenac Epolamine". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- 1 2 "RUFENAL". Birzeit Pharmaceutical Company. Archived from the original on 2011-05-26.

- ↑ cambiarx.com

- ↑ Dutta, NK; Mazumdar, K; Dastidar, SG; Park, JH (October 2007). "Activity of diclofenac used alone and in combination with streptomycin against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice.". International journal of antimicrobial agents. 30 (4): 336–40. PMID 17644321. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.04.016.

- ↑ mayoclinic.com

- ↑ cbg-meb.nl, SPC Netherlands

- ↑ Wakai A, Lawrenson JG, Lawrenson AL, Wang Y, Brown MD, Quirke M, Ghandour O, McCormick R, Walsh CD, Amayem A, Lang E, Harrison N (2017). "Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for analgesia in traumatic corneal abrasions". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 5: CD009781. PMID 28516471. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009781.pub2.

- ↑ WHO's pain ladder for adults

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Bhala, N.; Emberson, J.; et al. (2013). "Vascular and upper gastrointestinal effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: meta-analyses of individual participant data from randomised trials". The Lancet. 382 (9894): 769–779. PMC 3778977

. PMID 23726390. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60900-9.

. PMID 23726390. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60900-9. - ↑ Kearney PM, Baigent C, Godwin J, Halls H, Emberson JR, Patrono C (2006). "Do selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors and traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increase the risk of atherothrombosis? Meta-analysis of randomised trials". BMJ. 332 (7553): 1302–8. PMC 1473048

. PMID 16740558. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7553.1302.

. PMID 16740558. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7553.1302. - ↑ Solomon DH, Avorn J, Stürmer T, Glynn RJ, Mogun H, Schneeweiss S (2006). "Cardiovascular outcomes in new users of coxibs and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: high-risk subgroups and time course of risk". Arthritis Rheum. 54 (5): 1378–89. PMID 16645966. doi:10.1002/art.21887.

- ↑ Fosbøl EL, Folke F, Jacobsen S, Rasmussen JN, Sørensen R, Schramm TK, Andersen SS, Rasmussen S, Poulsen HE, Køber L, Torp-Pedersen C, Gislason GH (2010). "Cause-Specific Cardiovascular Risk Associated With Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs Among Healthy Individuals". Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 3 (4): 395–405. PMID 20530789. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.861104.

- ↑ BBC: Heart risk warning over painkiller diclofenac, 29 June 2013

- ↑ "Press release: Diclofenac tablets now only available as a prescription medicine". Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. January 14, 2015. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ↑ FitzGerald GA, Patrono C (2001). "The coxibs, selective inhibitors of cyclooxygenase-2". N Engl J Med. 345 (6): 433–42. PMID 11496855. doi:10.1056/NEJM200108093450607.

- ↑ Graham DJ (2006). "COX-2 inhibitors, other NSAIDs, and cardiovascular risk: the seduction of common sense". JAMA. 296 (13): 1653–6. PMID 16968830. doi:10.1001/jama.296.13.jed60058.

- ↑ fda.gov

- 1 2 Brater DC (2002). "Renal effects of cyclooxygyenase-2-selective inhibitors". J Pain Symptom Manage. 23 (4 Suppl): S15–20; discussion S21–3. PMID 11992745. doi:10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00370-6.

- ↑ http://www.nature.com/news/cattle-drug-threatens-thousands-of-vultures-1.19839

- ↑ "Diclofenac Side Effects". Drugs.com. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ↑ NSAIDS, Aspirin & Infertility http://www.fertilityplus.com/faq/nsaids.html

- ↑ Infertility May Sometimes Be Associated with NSAID Consumption http://rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org/content/35/1/76.full.pdf

- ↑ www.merck.com/mmpe/sec11/ch131/ch131b.html?qt=diclofenac&alt=sh#sec11-ch131-ch131b-174

- ↑ ABC News: Study links Voltaren to strokes http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2010/09/14/3011102.htm

- ↑ Dastidar SG, Ganguly K, Chaudhuri K, Chakrabarty AN (2000). "The anti-bacterial action of diclofenac shown by inhibition of DNA synthesis". Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 14 (3): 249–51. PMID 10773497. doi:10.1016/S0924-8579(99)00159-4.

- ↑ Fowler PD, Shadforth MF, Crook PR, John VA (1983). "Plasma and synovial fluid concentrations of diclofenac sodium and its major hydroxylated metabolites during long-term treatment of rheumatoid arthritis". Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 25 (3): 389–94. PMID 6628528. doi:10.1007/BF01037953.

- ↑ Scholer. Pharmacology of Diclofenac Sodium. Am J of Medicine Volume 80 April 28, 1986

- ↑ Voilley N, de Weille J, Mamet J, Lazdunski M: Nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs inhibit both the activity and the inflammation-induced expression of acid-sensing ion channels in nociceptors. J Neurosci. 2001 Oct 15;21(20):8026-33.

- ↑ Oaks JL, Gilbert M, Virani MZ, Watson RT, Meteyer CU, Rideout BA, Shivaprasad HL, Ahmed S, Chaudhry MJ, Arshad M, Mahmood S, Ali A, Khan AA (2004). "Diclofenac residues as the cause of vulture population decline in Pakistan". Nature. 427 (6975): 630–3. Bibcode:2004Natur.427..630O. PMID 14745453. doi:10.1038/nature02317.

- ↑ Swan, Gerry E.; Cuthbert, Richard; Quevedo, Miguel; Green, Rhys E.; Pain, Deborah J.; Bartels, Paul; Cunningham, Andrew A.; Duncan, Neil; Meharg, Andrew A.; Oaks, J. Lindsay; Parry-Jones, Jemima; Shultz, Susanne; Taggart, Mark A.; Verdoorn, Gerhard; Wolter, Kerri (2006-06-22). "Toxicity of diclofenac to Gyps vultures". Biology Letters. 2 (2): 279–282. ISSN 1744-9561. PMC 1618889

. PMID 17148382. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2005.0425.

. PMID 17148382. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2005.0425. - ↑ Naidoo V, Swan GE (August 2008). "Diclofenac toxicity in Gyps vulture is associated with decreased uric acid excretion and not renal portal vasoconstriction". Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 149 (3): 269–74. PMID 18727958. doi:10.1016/j.cbpc.2008.07.014.

- ↑ "Vet drug 'killing Asian vultures'". BBC News. 2004-02-28.

- 1 2 "Saving the Vultures from Extinction" (Press release). Press Information Bureau, Government of India. 2005-05-16. Retrieved 2006-05-12.

- 1 2 3 Swan G, Naidoo V, Cuthbert R, Green RE, Pain DJ, Swarup D, Prakash V, Taggart M, Bekker L, Das D, Diekmann J, Diekmann M, Killian E, Meharg A, Patra RC, Saini M, Wolter K (2006). "Removing the threat of diclofenac to critically endangered Asian vultures". PLoS Biol. 4 (3): e66. PMC 1351921

. PMID 16435886. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040066.

. PMID 16435886. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040066. - ↑ Gill, V. New drug threat to Asian vultures BBC News December 9, 2009.

- ↑ "Diclofenac Sodium | Diclofenac Sodium Gel | 75mg, 50mg". www.diclofenacsodium.info. Retrieved 2017-08-08.

- ↑ Phadnis, Mayuri (May 28, 2014). "Eagles fall prey to vulture-killing chemical". Pune Mirror. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- ↑ Schwaiger J, Ferling H, Mallow U, Wintermayr H, Negele RD (2004). "Toxic effects of the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac. Part I: Histopathological alterations and bioaccumulation in rainbow trout". Aquat. Toxicol. 68 (2): 141–150. PMID 15145224. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2004.03.014.

- ↑ Triebskorn R, Casper H, Heyd A, Eikemper R, Köhler HR, Schwaiger J (2004). "Toxic effects of the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac. Part II: Cytological effects in liver, kidney, gills and intestine of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss)". Aquat. Toxicol. 68 (2): 151–166. PMID 15145225. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2004.03.015.

- ↑ Schwaiger & Triebskorn (2005). UBA-Berichte 29/05: 217-226.

- ↑ Triebskorn R, Casper H, Scheil V, Schwaiger J (2007). "Ultrastructural effects of pharmaceuticals (carbamazepine, clofibric acid, metoprolol, diclofenac) in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and common carp (Cyprinus carpio)". Anal Bioanal Chem. 387 (4): 1405–16. PMID 17216161. doi:10.1007/s00216-006-1033-x.

- ↑ Rattner BA, Whitehead MA, Gasper G, Meteyer CU, Link WA, Taggart MA, Meharg AA, Pattee OH, Pain DJ (2009). "Apparent tolerance of turkey vultures (Cathartes aura) to the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac". Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 27 (11): 2341–2345. PMID 18476752. doi:10.1897/08-123.1.

- ↑ Rabies follows disruption in food cycle

- ↑ "E-010588/2015: answer given by Mr Andriukaitis on behalf of the Commission". European Parliament. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ↑ Becker, Rachel. "Cattle drug threatens thousands of vultures". Nature. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ↑ Vulture killing drug now available on EU market

- ↑ "A breakdown of the over-the-counter medicines market in Britain in 2016". Pharmaceutical Journal. 28 April 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ↑ https://www.gov.uk/drug-device-alerts/drug-alert-oral-diclofenac-presentations-with-legal-status-p-reclassified-to-pom

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Diclofenac. |

- Diclofenac: Drug Information Provided by Lexi-Comp: Merck Manual Professional

- Cancer Treatment with Diclofenac – What Are the Facts?