Castleman's disease

| Castleman disease | |

|---|---|

| |

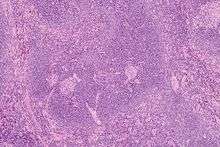

| Micrograph of Castleman disease, hyaline vascular variant, exhibiting the characteristically expanded mantle zone and a radially penetrating sclerotic blood vessel ("lollipop" sign). H&E stain. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | D47.4 |

| ICD-9-CM | 785.6 |

| DiseasesDB | 2165 |

| MeSH | D005871 |

Castleman disease, also known as giant lymph node hyperplasia, lymphoid hamartoma, or angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia, is a group of uncommon lymphoproliferative disorders that share common lymph node histological features. It is named after Benjamin Castleman.[1][2]

Castleman's disease has two main forms: It may be localized to a single lymph node (unicentric) or occur systemically (multicentric).

The unicentric form can usually be cured by surgically removing the lymph node, with a 10-year survival of 95%.[3]

Multicentric Castleman disease (MCD) involves hyperactivation of the immune system, excessive release of proinflammatory chemicals (cytokines), proliferation of immune cells (B cells and T cells), and multiple organ system dysfunction.[4] Castleman disease must be distinguished from other disorders that can demonstrate "Castleman-like" lymph node features, including reactive lymph node hyperplasia, autoimmune disorders, and malignancies.[5] Multicentric Castleman's disease is associated with lymphoma and Kaposi's sarcoma.[6]

Signs and symptoms

MCD clinical features range from waxing and waning mild enlargement of the lymph nodes with B symptoms to more severe cases involving intense inflammation, widespread enlargement of lymph nodes enlargement of the liver and spleen, vascular leak syndrome with anasarca, fluid collections in the space around the lungs, and fluid collection in the abdomen's peritoneal space, organ failure, and even death. The most common 'B Symptoms' of MCD are high fevers, night sweats, weight loss, and loss of appetite. Acute episodes can display significant clinical overlap with acute viral illnesses, autoimmune diseases, hematologic malignancies, and even sepsis. Laboratory findings commonly include low red blood cell count, low or high platelet counts, low albumin, high gamma globulin levels, elevated C-reactive protein levels, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, IL-6, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and fibrinogen; positive anti-nuclear antibody, anti-erythrocyte autoantibodies, and anti-platelet antibodies; and protein spilling into the urine, and polyclonal marrow plasmacytosis. Castleman disease is seen in POEMS syndrome and is implicated in 10% of cases of paraneoplastic pemphigus.

Pathogenesis

Lymph node abnormalities and organ dysfunction in Castleman disease are caused by excessive secretion of cytokines. IL-6 is the most commonly elevated cytokine,[7] but some affected people may have normal IL-6 levels and present with non-iron-deficient microcytic anemia.[5]

The release of these cytokines is caused by infection with Human herpesvirus 8 in HHV-8-associated MCD. The cause of the release of cytokines in idiopathic MCD has been hypothesized to be caused by either a somatic mutation, a germline genetic mutation, or a non-HHV-8-virus.[4]

Diagnosis

Castleman disease is diagnosed when a lymph node biopsy reveals regression of germinal centers, abnormal vascularity, and a range of hyaline vascular changes and/or polytypic plasma cell proliferation. These features can also be seen in other disorders involving excessive cytokine release, so they must be excluded before a Castleman disease diagnosis should be made.

It is essential for the biopsy sample to be tested for HHV-8 with latent associated nuclear antigen (LANA) by immunohistochemistry or PCR for HHV-8 in the blood.

Types

There are three sub-types of Castleman disease.

- Unicentric Castleman disease

- HHV-8-associated multicentric Castleman disease

- HHV-8-negative multicentric Castleman disease

Unicentric vs. multicentric

Unicentric Castleman disease involves "Castleman-like" lymph node changes at only a single site. Enlarged lymph nodes in the chest can press on the windpipe (trachea) or smaller breathing tubes going into the lungs (bronchi), causing breathing problems. If the enlarged nodes are in the abdomen, the person might have pain, a feeling of fullness, or trouble eating. In at least 90% of cases, removal of the enlarged node is curative with no further complications.

Multicentric Castleman disease (MCD) involves "Castleman-like" lymph node changes at multiple sites and patients often demonstrate intense episodes of systemic inflammatory symptoms, polyclonal/reactive lymphocyte and plasma cell proliferation, autoimmune manifestations, and multiple organ system impairment.[4][8]

- HHV-8-associated Multicentric Castleman disease HHV-8, also called KSHV, is a gammaherpesvirus that is responsible for causing approximately 50% of MCD cases by driving excessive cytokine release secondary to the expression of the virus-encoded cytokine, vIL-6.[9] These cases are referred to as HHV-8-associated MCD and all demonstrate "plasmablastic" lymph node features. HHV-8 also causes Kaposi's sarcoma and primary effusion lymphoma. Most cases of HHV-8-associated MCD are also HIV positive, because HIV and other causes of immunosuppression prevent the body from being able to control HHV-8 viral replication. This is most likely due to expression of the virus

- HHV-8-negative Multicentric Castleman disease The cause for immune activation that is responsible for the other 50% of MCD cases is unknown. These cases are referred to as idiopathic MCD. Idiopathic MCD can demonstrate hyaline vascular, plasmacytic, or mixed lymph node features.[4]

Treatment

Unicentric

In the unicentric form of the disease, surgical resection is often curative,[5][10] and the prognosis is excellent.

HHV-8-associated multicentric

There is no standard therapy for multicentric Castleman disease. Treatment modalities change based on HHV-8 status, so it is essential to determine HHV-8 status before beginning treatment. For HHV-8-associated MCD the following treatments have been used: rituximab, antiviral medications such as ganciclovir, and chemotherapy.[11]

Treatment with the antiherpesvirus medication ganciclovir or the anti-CD20 B cell monoclonal antibody, rituximab, may markedly improve outcomes. These medications target and kill B cells via the B cell specific CD20 marker. Since B cells are required for the production of antibodies, the body's immune response is weakened whilst on treatment and the risk of further viral or bacterial infection is increased. Due to the uncommon nature of the condition there are not many large scale research studies from which standardized approaches to therapy may be drawn, and the extant case studies of individuals or small cohorts should be read with caution. As with many diseases, the patient's age, physical state and previous medical history with respect to infections may impact the disease progression and outcome.

HHV-8-negative multicentric

For HHV-8-negative MCD (idiopathic MCD), the following treatments have been used: corticosteroids, rituximab, monoclonal antibodies against IL-6 such as tocilizumab and siltuximab, and the immunomodulator thalidomide.[12]

Prior to 1996 MCD carried a poor prognosis of about 2 years, due to autoimmune hemolytic anemia and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma which may arise as a result of proliferation of infected cells. The timing of diagnosis, with particular attention to the difficulty of determining the cause of B symptoms without a CT scan and lymph node biopsy, may have a significant impact on the prognosis and risk of death. Left untreated, MCD usually gets worse and becomes increasingly difficult and unresponsive to current treatment regimens.

Siltuximab prevents it from binding to the IL-6 receptor, was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of multicentric Castleman disease on April 23, 2014.[13][14] Preliminary data suggest that treatment siltuximab may achieve tumour and symptomatic response in 34% of patients with MCD.[15]

Other treatments for multicentric Castleman disease include the following:

Research

A new model of pathogenesis (lymph node changes are not “benign tumors” that secrete cytokines, but reactive changes due to excessive cytokine release from an as-yet unknown cause) and a new classification system for MCD (based on HHV-8 status) have ensued.[4] CDCN has launched a platform for online discussion among physicians and researchers, developed a global research agenda, and launched a global patient community in partnership with EURODIS and NORD. Current strategic priorities include: 1) establishing a global patient registry, 2) empowering the global patient community to support one another and join the fight against CD, and 3) distributing high-impact research grants.

See also

References

- ↑ synd/3017 at Who Named It?

- ↑ Castleman B, Iverson L, Menendez VP. "Localized mediastinal lymphnode hyperplasia resembling".

- ↑ Cokelaere et al., Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:662-9

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fajgenbaum, David; van Rhee, Frits; Nabel, Chris (May 8, 2014). "HHV-8-negative, idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease: novel insights into biology, pathogenesis, and therapy". Blood. 123 (19): 2924–33. PMID 24622327. doi:10.1182/blood-2013-12-545087.

- 1 2 3 Weng, Chien-Hsiang; Joe-Bin Chen; John Wang; Cheng-Chung Wu; Yuan Yu; Tseng-Hsi Lin (23 August 2011). "Surgically Curable Non-Iron Deficiency Microcytic Anemia: Castleman Disease". Onkologie. 34 (8-9): 456–458. PMID 21934347. doi:10.1159/000331283.

- ↑ "Castleman disease". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2010-02-03.

- ↑ Ahmed B, Tschen JA, Cohen PR, et al. (September 2007). "Cutaneous Castleman disease responds to anti interleukin-6 treatment". Mol. Cancer Ther. 6 (9): 2386–90. PMID 17766835. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0256.

- ↑ Menezes BF, Morgan R, Azad M (2007). "Multicentric Castleman disease: a case report". J Med Case Reports. 1: 78. PMC 2014764

. PMID 17803812. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-1-78.

. PMID 17803812. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-1-78. - ↑ Aoki Y, Yarchoan R, Wyvill K, Okamoto S, Little RF, Tosato G (April 2001). "Detection of viral interleukin-6 in Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-linked disorders". Blood. 97 (7): 2173–6. PMID 11264189. doi:10.1182/blood.V97.7.2173.

- ↑ Talarico F, Negri L, Iusco D, Corazza GG (April 2008). "Unicentric Castleman disease in peripancreatic tissue: case report and review of the literature". G Chir. 29 (4): 141–4. PMID 18419976.

- ↑ Sprinz E, Jeffman M, Liedke P, Putten A, Schwartsmann G (February 2004). "Successful treatment of AIDS-related Castleman disease following the administration of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART)". Ann. Oncol. 15 (2): 356–8. PMID 14760135. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdh066.

- ↑ Matsuyama M, Suzuki T, Tsuboi H, et al. (2007). "Anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody (tocilizumab) treatment of multicentric Castleman disease". Intern. Med. 46 (11): 771–4. PMID 17541233. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.46.6262. Archived from the original (– Scholar search) on 2012-12-19.

- ↑ "A Study to Evaluate the Safety of Long-term Treatment With Siltuximab in Patients With Multicentric Castleman Disease". ClinalTrails.gov.

- ↑ "FDA approves Sylvant for rare Castleman’s disease". FDA.gov. April 23, 2014.

- ↑ Wong, Raymond; Corey Casper; Nikhil Munshi; Xiaoyan Ke; Alexander Fosså; David Simpson; Marcelo Capra; Ting Liu; Ruey Kuen Hsieh; Yeow Tee Goh; Jun Zhu; Seok-Goo Cho; Hanyun Ren; James Cavet; Rajesh Bandekar; Margaret Rothman; Thomas A Puchalski; Shalini Chaturvedi; Helgi van de Velde; Jessica Vermeulen; Frits van Rhee (9 December 2013). A Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study Of The Efficacy and Safety Of Siltuximab, An Anti-Interleukin-6 Monoclonal Antibody, In Patients With Multicentric Castleman Disease. American Society of Hematology 55th Annual Meeting. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ↑ http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/castleman-disease/DS01000/DSECTION=treatments-and-drugs

External links

- International Castlemans Disease Organization

- Castleman's Awareness and Research Effort

- Castleman Disease Collaborative Network

- Orphanet: Castleman disease