Casting (metalworking)

In metalworking, casting means a process, in which liquid metal is poured into a mold, that contains a hollow cavity of the desired shape, and is then allowed to cool and solidify. The solidified part is also known as a casting, which is ejected or broken out of the mold to complete the process. Casting is most often used for making complex shapes that would be difficult or uneconomical to make by other methods.[1]

Casting processes have been known for thousands of years, and widely used for sculpture, especially in bronze, jewellery in precious metals, and weapons and tools. Traditional techniques include lost-wax casting, plaster mold casting and sand casting.

The modern casting process is subdivided into two main categories: expendable and non-expendable casting. It is further broken down by the mold material, such as sand or metal, and pouring method, such as gravity, vacuum, or low pressure.[2]

Expendable mold casting

Expendable mold casting is a generic classification that includes sand, plastic, shell, plaster, and investment (lost-wax technique) moldings. This method of mold casting involves the use of temporary, non-reusable molds.

Sand casting

Sand casting is one of the most popular and simplest types of casting, and has been used for centuries. Sand casting allows for smaller batches than permanent mold casting and at a very reasonable cost. Not only does this method allow manufacturers to create products at a low cost, but there are other benefits to sand casting, such as very small-size operations. The process allows for castings small enough fit in the palm of one's hand to those large enough only for train beds (one casting can create the entire bed for one rail car). Sand casting also allows most metals to be cast depending on the type of sand used for the molds.[3]

Sand casting requires a lead time of days, or even weeks sometimes, for production at high output rates (1–20 pieces/hr-mold) and is unsurpassed for large-part production. Green (moist) sand has almost no part weight limit, whereas dry sand has a practical part mass limit of 2,300–2,700 kg (5,100–6,000 lb). Minimum part weight ranges from 0.075–0.1 kg (0.17–0.22 lb). The sand is bonded together using clays, chemical binders, or polymerized oils (such as motor oil). Sand can be recycled many times in most operations and requires little maintenance.

Plaster mold casting

Plaster casting is similar to sand casting except that plaster of paris is substituted for sand as a mold material. Generally, the form takes less than a week to prepare, after which a production rate of 1–10 units/hr·mold is achieved, with items as massive as 45 kg (99 lb) and as small as 30 g (1 oz) with very good surface finish and close tolerances.[4] Plaster casting is an inexpensive alternative to other molding processes for complex parts due to the low cost of the plaster and its ability to produce near net shape castings. The biggest disadvantage is that it can only be used with low melting point non-ferrous materials, such as aluminium, copper, magnesium, and zinc.[5]

Shell molding

Shell molding is similar to sand casting, but the molding cavity is formed by a hardened "shell" of sand instead of a flask filled with sand. The sand used is finer than sand casting sand and is mixed with a resin so that it can be heated by the pattern and hardened into a shell around the pattern. Because of the resin and finer sand, it gives a much finer surface finish. The process is easily automated and more precise than sand casting. Common metals that are cast include cast iron, aluminium, magnesium, and copper alloys. This process is ideal for complex items that are small to medium-sized.

Investment casting

Investment casting (known as lost-wax casting in art) is a process that has been practiced for thousands of years, with the lost-wax process being one of the oldest known metal forming techniques. From 5000 years ago, when beeswax formed the pattern, to today’s high technology waxes, refractory materials and specialist alloys, the castings ensure high-quality components are produced with the key benefits of accuracy, repeatability, versatility and integrity.

Investment casting derives its name from the fact that the pattern is invested, or surrounded, with a refractory material. The wax patterns require extreme care for they are not strong enough to withstand forces encountered during the mold making. One advantage of investment casting is that the wax can be reused.[4]

The process is suitable for repeatable production of net shape components from a variety of different metals and high performance alloys. Although generally used for small castings, this process has been used to produce complete aircraft door frames, with steel castings of up to 300 kg and aluminium castings of up to 30 kg. Compared to other casting processes such as die casting or sand casting, it can be an expensive process. However, the components that can be produced using investment casting can incorporate intricate contours, and in most cases the components are cast near net shape, so require little or no rework once cast.

Waste molding of plaster

A durable plaster intermediate is often used as a stage toward the production of a bronze sculpture or as a pointing guide for the creation of a carved stone. With the completion of a plaster, the work is more durable (if stored indoors) than a clay original which must be kept moist to avoid cracking. With the low cost plaster at hand, the expensive work of bronze casting or stone carving may be deferred until a patron is found, and as such work is considered to be a technical, rather than artistic process, it may even be deferred beyond the lifetime of the artist.

In waste molding a simple and thin plaster mold, reinforced by sisal or burlap, is cast over the original clay mixture. When cured, it is then removed from the damp clay, incidentally destroying the fine details in undercuts present in the clay, but which are now captured in the mold. The mold may then at any later time (but only once) be used to cast a plaster positive image, identical to the original clay. The surface of this plaster may be further refined and may be painted and waxed to resemble a finished bronze casting.

Evaporative-pattern casting

This is a class of casting processes that use pattern materials that evaporate during the pour, which means there is no need to remove the pattern material from the mold before casting. The two main processes are lost-foam casting and full-mold casting.

Lost-foam casting

Lost-foam casting is a type of evaporative-pattern casting process that is similar to investment casting except foam is used for the pattern instead of wax. This process takes advantage of the low boiling point of foam to simplify the investment casting process by removing the need to melt the wax out of the mold.

Full-mold casting

Full-mold casting is an evaporative-pattern casting process which is a combination of sand casting and lost-foam casting. It uses an expanded polystyrene foam pattern which is then surrounded by sand, much like sand casting. The metal is then poured directly into the mold, which vaporizes the foam upon contact.

Non-expendable mold casting

Non-expendable mold casting differs from expendable processes in that the mold need not be reformed after each production cycle. This technique includes at least four different methods: permanent, die, centrifugal, and continuous casting. This form of casting also results in improved repeatability in parts produced and delivers Near Net Shape results.

Permanent mold casting

Permanent mold casting is a metal casting process that employs reusable molds ("permanent molds"), usually made from metal. The most common process uses gravity to fill the mold. However, gas pressure or a vacuum are also used. A variation on the typical gravity casting process, called slush casting, produces hollow castings. Common casting metals are aluminum, magnesium, and copper alloys. Other materials include tin, zinc, and lead alloys and iron and steel are also cast in graphite molds. Permanent molds, while lasting more than one casting still have a limited life before wearing out.

Die casting

The die casting process forces molten metal under high pressure into mold cavities (which are machined into dies). Most die castings are made from nonferrous metals, specifically zinc, copper, and aluminium-based alloys, but ferrous metal die castings are possible. The die casting method is especially suited for applications where many small to medium-sized parts are needed with good detail, a fine surface quality and dimensional consistency.

Semi-solid metal casting

Semi-solid metal (SSM) casting is a modified die casting process that reduces or eliminates the residual porosity present in most die castings. Rather than using liquid metal as the feed material, SSM casting uses a higher viscosity feed material that is partially solid and partially liquid. A modified die casting machine is used to inject the semi-solid slurry into re-usable hardened steel dies. The high viscosity of the semi-solid metal, along with the use of controlled die filling conditions, ensures that the semi-solid metal fills the die in a non-turbulent manner so that harmful porosity can be essentially eliminated.

Used commercially mainly for aluminium and magnesium alloys, SSM castings can be heat treated to the T4, T5 or T6 tempers. The combination of heat treatment, fast cooling rates (from using un-coated steel dies) and minimal porosity provides excellent combinations of strength and ductility. Other advantages of SSM casting include the ability to produce complex shaped parts net shape, pressure tightness, tight dimensional tolerances and the ability to cast thin walls.[6]

Centrifugal casting

In this process molten metal is poured in the mold and allowed to solidify while the mold is rotating. Metal is poured into the center of the mold at its axis of rotation. Due to centrifugal force the liquid metal is thrown out towards the periphery.

Centrifugal casting is both gravity- and pressure-independent since it creates its own force feed using a temporary sand mold held in a spinning chamber at up to 900 N. Lead time varies with the application. Semi- and true-centrifugal processing permit 30–50 pieces/hr-mold to be produced, with a practical limit for batch processing of approximately 9000 kg total mass with a typical per-item limit of 2.3–4.5 kg.

Industrially, the centrifugal casting of railway wheels was an early application of the method developed by the German industrial company Krupp and this capability enabled the rapid growth of the enterprise.

Small art pieces such as jewelry are often cast by this method using the lost wax process, as the forces enable the rather viscous liquid metals to flow through very small passages and into fine details such as leaves and petals. This effect is similar to the benefits from vacuum casting, also applied to jewelry casting.

Continuous casting

Continuous casting is a refinement of the casting process for the continuous, high-volume production of metal sections with a constant cross-section. Molten metal is poured into an open-ended, water-cooled mold, which allows a 'skin' of solid metal to form over the still-liquid centre, gradually solidifying the metal from the outside in. After solidification, the strand, as it is sometimes called, is continuously withdrawn from the mold. Predetermined lengths of the strand can be cut off by either mechanical shears or traveling oxyacetylene torches and transferred to further forming processes, or to a stockpile. Cast sizes can range from strip (a few millimeters thick by about five meters wide) to billets (90 to 160 mm square) to slabs (1.25 m wide by 230 mm thick). Sometimes, the strand may undergo an initial hot rolling process before being cut.

Continuous casting is used due to the lower costs associated with continuous production of a standard product, and also increased quality of the final product. Metals such as steel, copper, aluminum and lead are continuously cast, with steel being the metal with the greatest tonnages cast using this method.

Terminology

Metal casting processes uses the following terminology:[7]

- Pattern: An approximate duplicate of the final casting used to form the mold cavity.

- Molding material: The material that is packed around the pattern and then the pattern is removed to leave the cavity where the casting material will be poured.

- Flask: The rigid wood or metal frame that holds the molding material.

- Core: An insert in the mold that produces internal features in the casting, such as holes.

- Core print: The region added to the pattern, core, or mold used to locate and support the core.

- Mold cavity: The combined open area of the molding material and core, where the metal is poured to produce the casting.

- Riser: An extra void in the mold that fills with molten material to compensate for shrinkage during solidification.

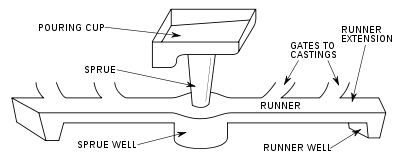

- Gating system: The network of connected channels that deliver the molten material to the mold cavities.

- Pouring cup or pouring basin: The part of the gating system that receives the molten material from the pouring vessel.

- Sprue: The pouring cup attaches to the sprue, which is the vertical part of the gating system. The other end of the sprue attaches to the runners.

- Runners: The horizontal portion of the gating system that connects the sprues to the gates.

- Gates: The controlled entrances from the runners into the mold cavities.

- Vents: Additional channels that provide an escape for gases generated during the pour.

- Parting line or parting surface: The interface between the cope and drag halves of the mold, flask, or pattern.

- Draft: The taper on the casting or pattern that allow it to be withdrawn from the mold

- Core box: The mold or die used to produce the cores.

- Chaplet: Long vertical holding rod for core that after casting it become the integral part of casting, provide the suppot to the core.

Some specialized processes, such as die casting, use additional terminology.

Theory

Casting is a solidification process, which means the solidification phenomenon controls most of the properties of the casting. Moreover, most of the casting defects occur during solidification, such as gas porosity and solidification shrinkage.[8]

Solidification occurs in two steps: nucleation and crystal growth. In the nucleation stage solid particles form within the liquid. When these particles form their internal energy is lower than the surrounded liquid, which creates an energy interface between the two. The formation of the surface at this interface requires energy, so as nucleation occurs the material actually undercools, that is it cools below its freezing temperature, because of the extra energy required to form the interface surfaces. It then recalescences, or heats back up to its freezing temperature, for the crystal growth stage. Note that nucleation occurs on a pre-existing solid surface, because not as much energy is required for a partial interface surface, as is for a complete spherical interface surface. This can be advantageous because fine-grained castings possess better properties than coarse-grained castings. A fine grain structure can be induced by grain refinement or inoculation, which is the process of adding impurities to induce nucleation.[9]

All of the nucleations represent a crystal, which grows as the heat of fusion is extracted from the liquid until there is no liquid left. The direction, rate, and type of growth can be controlled to maximize the properties of the casting. Directional solidification is when the material solidifies at one end and proceeds to solidify to the other end; this is the most ideal type of grain growth because it allows liquid material to compensate for shrinkage.[9]

Cooling curves

Cooling curves are important in controlling the quality of a casting. The most important part of the cooling curve is the cooling rate which affects the microstructure and properties. Generally speaking, an area of the casting which is cooled quickly will have a fine grain structure and an area which cools slowly will have a coarse grain structure. Below is an example cooling curve of a pure metal or eutectic alloy, with defining terminology.[10]

Note that before the thermal arrest the material is a liquid and after it the material is a solid; during the thermal arrest the material is converting from a liquid to a solid. Also, note that the greater the superheat the more time there is for the liquid material to flow into intricate details.[11]

The above cooling curve depicts a basic situation with a pure alloy, however, most castings are of alloys, which have a cooling curve shaped as shown below.

Note that there is no longer a thermal arrest, instead there is a freezing range. The freezing range corresponds directly to the liquidus and solidus found on the phase diagram for the specific alloy.

Chvorinov's rule

The local solidification time can be calculated using Chvorinov's rule, which is:

Where t is the solidification time, V is the volume of the casting, A is the surface area of the casting that contacts the mold, n is a constant, and B is the mold constant. It is most useful in determining if a riser will solidify before the casting, because if the riser does solidify first then it is worthless.[12]

The gating system

The gating system serves many purposes, the most important being conveying the liquid material to the mold, but also controlling shrinkage, the speed of the liquid, turbulence, and trapping dross. The gates are usually attached to the thickest part of the casting to assist in controlling shrinkage. In especially large castings multiple gates or runners may be required to introduce metal to more than one point in the mold cavity. The speed of the material is important because if the material is traveling too slowly it can cool before completely filling, leading to misruns and cold shuts. If the material is moving too fast then the liquid material can erode the mold and contaminate the final casting. The shape and length of the gating system can also control how quickly the material cools; short round or square channels minimize heat loss.[13]

The gating system may be designed to minimize turbulence, depending on the material being cast. For example, steel, cast iron, and most copper alloys are turbulent insensitive, but aluminium and magnesium alloys are turbulent sensitive. The turbulent insensitive materials usually have a short and open gating system to fill the mold as quickly as possible. However, for turbulent sensitive materials short sprues are used to minimize the distance the material must fall when entering the mold. Rectangular pouring cups and tapered sprues are used to prevent the formation of a vortex as the material flows into the mold; these vortices tend to suck gas and oxides into the mold. A large sprue well is used to dissipate the kinetic energy of the liquid material as it falls down the sprue, decreasing turbulence. The choke, which is the smallest cross-sectional area in the gating system used to control flow, can be placed near the sprue well to slow down and smooth out the flow. Note that on some molds the choke is still placed on the gates to make separation of the part easier, but induces extreme turbulence.[14] The gates are usually attached to the bottom of the casting to minimize turbulence and splashing.[13]

The gating system may also be designed to trap dross. One method is to take advantage of the fact that some dross has a lower density than the base material so it floats to the top of the gating system. Therefore, long flat runners with gates that exit from the bottom of the runners can trap dross in the runners; note that long flat runners will cool the material more rapidly than round or square runners. For materials where the dross is a similar density to the base material, such as aluminium, runner extensions and runner wells can be advantageous. These take advantage of the fact that the dross is usually located at the beginning of the pour, therefore the runner is extended past the last gate(s) and the contaminates are contained in the wells. Screens or filters may also be used to trap contaminates.[14]

It is important to keep the size of the gating system small, because it all must be cut from the casting and remelted to be reused. The efficiency, or yield, of a casting system can be calculated by dividing the weight of the casting by the weight of the metal poured. Therefore, the higher the number the more efficient the gating system/risers.[15]

Shrinkage

There are three types of shrinkage: shrinkage of the liquid, solidification shrinkage and patternmaker's shrinkage. The shrinkage of the liquid is rarely a problem because more material is flowing into the mold behind it. Solidification shrinkage occurs because metals are less dense as a liquid than a solid, so during solidification the metal density dramatically increases. Patternmaker's shrinkage refers to the shrinkage that occurs when the material is cooled from the solidification temperature to room temperature, which occurs due to thermal contraction.[16]

Solidification shrinkage

| Metal | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Aluminium | 6.6 |

| Copper | 4.9 |

| Magnesium | 4.0 or 4.2 |

| Zinc | 3.7 or 6.5 |

| Low carbon steel | 2.5–3.0 |

| High carbon steel | 4.0 |

| White cast iron | 4.0–5.5 |

| Gray cast iron | −2.5–1.6 |

| Ductile cast iron | −4.5–2.7 |

Most materials shrink as they solidify, but, as the adjacent table shows, a few materials do not, such as gray cast iron. For the materials that do shrink upon solidification the type of shrinkage depends on how wide the freezing range is for the material. For materials with a narrow freezing range, less than 50 °C (122 °F),[19] a cavity, known as a pipe, forms in the center of the casting, because the outer shell freezes first and progressively solidifies to the center. Pure and eutectic metals usually have narrow solidification ranges. These materials tend to form a skin in open air molds, therefore they are known as skin forming alloys.[19] For materials with a wide freezing range, greater than 110 °C (230 °F),[19] much more of the casting occupies the mushy or slushy zone (the temperature range between the solidus and the liquidus), which leads to small pockets of liquid trapped throughout and ultimately porosity. These castings tend to have poor ductility, toughness, and fatigue resistance. Moreover, for these types of materials to be fluid-tight a secondary operation is required to impregnate the casting with a lower melting point metal or resin.[17][20]

For the materials that have narrow solidification ranges pipes can be overcome by designing the casting to promote directional solidification, which means the casting freezes first at the point farthest from the gate, then progressively solidifies towards the gate. This allows a continuous feed of liquid material to be present at the point of solidification to compensate for the shrinkage. Note that there is still a shrinkage void where the final material solidifies, but if designed properly this will be in the gating system or riser.[17]

Risers and riser aids

Risers, also known as feeders, are the most common way of providing directional solidification. It supplies liquid metal to the solidifying casting to compensate for solidification shrinkage. For a riser to work properly the riser must solidify after the casting, otherwise it cannot supply liquid metal to shrinkage within the casting. Risers add cost to the casting because it lowers the yield of each casting; i.e. more metal is lost as scrap for each casting. Another way to promote directional solidification is by adding chills to the mold. A chill is any material which will conduct heat away from the casting more rapidly than the material used for molding.[21]

Risers are classified by three criteria. The first is if the riser is open to the atmosphere, if it is then it is called an open riser, otherwise it is known as a blind type. The second criterion is where the riser is located; if it is located on the casting then it is known as a top riser and if it is located next to the casting it is known as a side riser. Finally, if the riser is located on the gating system so that it fills after the molding cavity, it is known as a live riser or hot riser, but if the riser fills with materials that have already flowed through the molding cavity it is known as a dead riser or cold riser.[15]

Riser aids are items used to assist risers in creating directional solidification or reducing the number of risers required. One of these items are chills which accelerate cooling in a certain part of the mold. There are two types: external and internal chills. External chills are masses of high-heat-capacity and high-thermal-conductivity material that are placed on an edge of the molding cavity. Internal chills are pieces of the same metal that is being poured, which are placed inside the mold cavity and become part of the casting. Insulating sleeves and toppings may also be installed around the riser cavity to slow the solidification of the riser. Heater coils may also be installed around or above the riser cavity to slow solidification.[22]

Patternmaker's shrink

| Metal | Percentage | in/ft |

|---|---|---|

| Aluminium | 1.0–1.3 | 1⁄8– 5⁄32 |

| Brass | 1.5 | 3⁄16 |

| Magnesium | 1.0–1.3 | 1⁄8– 5⁄32 |

| Cast iron | 0.8–1.0 | 1⁄10– 1⁄8 |

| Steel | 1.5–2.0 | 3⁄16– 1⁄4 |

Shrinkage after solidification can be dealt with by using an oversized pattern designed specifically for the alloy used. Contraction rules, or shrink rules, are used to make the patterns oversized to compensate for this type of shrinkage.[23] These rulers are up to 2.5% oversize, depending on the material being cast.[22] These rulers are mainly referred to by their percentage change. A pattern made to match an existing part would be made as follows: First, the existing part would be measured using a standard ruler, then when constructing the pattern, the pattern maker would use a contraction rule, ensuring that the casting would contract to the correct size.

Note that patternmaker's shrinkage does not take phase change transformations into account. For example, eutectic reactions, martensitic reactions, and graphitization can cause expansions or contractions.[23]

Mold cavity

The mold cavity of a casting does not reflect the exact dimensions of the finished part due to a number of reasons. These modifications to the mold cavity are known as allowances and account for patternmaker's shrinkage, draft, machining, and distortion. In non-expendable processes, these allowances are imparted directly into the permanent mold, but in expendable mold processes they are imparted into the patterns, which later form the mold cavity.[23] Note that for non-expendable molds an allowance is required for the dimensional change of the mold due to heating to operating temperatures.[24]

For surfaces of the casting that are perpendicular to the parting line of the mold a draft must be included. This is so that the casting can be released in non-expendable processes or the pattern can be released from the mold without destroying the mold in expendable processes. The required draft angle depends on the size and shape of the feature, the depth of the mold cavity, how the part or pattern is being removed from the mold, the pattern or part material, the mold material, and the process type. Usually the draft is not less than 1%.[23]

The machining allowance varies drastically from one process to another. Sand castings generally have a rough surface finish, therefore need a greater machining allowance, whereas die casting has a very fine surface finish, which may not need any machining tolerance. Also, the draft may provide enough of a machining allowance to begin with.[24]

The distortion allowance is only necessary for certain geometries. For instance, U-shaped castings will tend to distort with the legs splaying outward, because the base of the shape can contract while the legs are constrained by the mold. This can be overcome by designing the mold cavity to slope the leg inward to begin with. Also, long horizontal sections tend to sag in the middle if ribs are not incorporated, so a distortion allowance may be required.[24]

Cores may be used in expendable mold processes to produce internal features. The core can be of metal but it is usually done in sand.

Filling

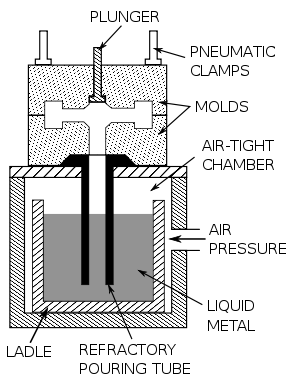

There are a few common methods for filling the mold cavity: gravity, low-pressure, high-pressure, and vacuum.[25]

Vacuum filling, also known as counter-gravity filling, is more metal efficient than gravity pouring because less material solidifies in the gating system. Gravity pouring only has a 15 to 50% metal yield as compared to 60 to 95% for vacuum pouring. There is also less turbulence, so the gating system can be simplified since it does not have to control turbulence. Plus, because the metal is drawn from below the top of the pool the metal is free from dross and slag, as these are lower density (lighter) and float to the top of the pool. The pressure differential helps the metal flow into every intricacy of the mold. Finally, lower temperatures can be used, which improves the grain structure.[25] The first patented vacuum casting machine and process dates to 1879.[26]

Low-pressure filling uses 5 to 15 psig (35 to 100 kPag) of air pressure to force liquid metal up a feed tube into the mold cavity. This eliminates turbulence found in gravity casting and increases density, repeatability, tolerances, and grain uniformity. After the casting has solidified the pressure is released and any remaining liquid returns to the crucible, which increases yield.[27]

Tilt filling

Tilt filling, also known as tilt casting, is an uncommon filling technique where the crucible is attached to the gating system and both are slowly rotated so that the metal enters the mold cavity with little turbulence. The goal is to reduce porosity and inclusions by limiting turbulence. For most uses tilt filling is not feasible because the following inherent problem: if the system is rotated slow enough to not induce turbulence, the front of the metal stream begins to solidify, which results in mis-runs. If the system is rotated faster it induces turbulence, which defeats the purpose. Durville of France was the first to try tilt casting, in the 1800s. He tried to use it to reduce surface defects when casting coinage from aluminium bronze.[28]

Macrostructure

The grain macrostructure in ingots and most castings have three distinct regions or zones: the chill zone, columnar zone, and equiaxed zone. The image below depicts these zones.

The chill zone is named so because it occurs at the walls of the mold where the wall chills the material. Here is where the nucleation phase of the solidification process takes place. As more heat is removed the grains grow towards the center of the casting. These are thin, long columns that are perpendicular to the casting surface, which are undesirable because they have anisotropic properties. Finally, in the center the equiaxed zone contains spherical, randomly oriented crystals. These are desirable because they have isotropic properties. The creation of this zone can be promoted by using a low pouring temperature, alloy inclusions, or inoculants.[12]

Inspection

Common inspection methods for steel castings are magnetic particle testing and liquid penetrant testing.[29] Common inspection methods for aluminum castings are radiography, ultrasonic testing, and liquid penetrant testing.[30]

Defects

There are a number of problems that can be encountered during the casting process. The main types are: gas porosity, shrinkage defects, mold material defects, pouring metal defects, and metallurgical defects.

Casting Process Simulation

Casting process simulation uses numerical methods to calculate cast component quality considering mold filling, solidification and cooling, and provides a quantitative prediction of casting mechanical properties, thermal stresses and distortion. Simulation accurately describes a cast component’s quality up-front before production starts. The casting rigging can be designed with respect to the required component properties. This has benefits beyond a reduction in pre-production sampling, as the precise layout of the complete casting system also leads to energy, material, and tooling savings.

The software supports the user in component design, the determination of melting practice and casting methoding through to pattern and mold making, heat treatment, and finishing. This saves costs along the entire casting manufacturing route.

Casting process simulation was initially developed at universities starting from the early '70s, mainly in Europe and in the U.S., and is regarded as the most important innovation in casting technology over the last 50 years. Since the late '80s, commercial programs are available which make it possible for foundries to gain new insight into what is happening inside the mold or die during the casting process.

See also

- Bronze sculpture

- Bronze and brass ornamental work

- Flexible mold

- Porosity sealing

- Spin casting

- Spray forming

References

Notes

- ↑ Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 277

- ↑ Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 278

- ↑ Schleg et al. 2003, chapters 2–4.

- 1 2 Kalpakjian & Schmid 2006.

- ↑ Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 315

- ↑ 10th International Conference Semi-Solid Processing of Alloys and Composites, Eds. G. Hirt, A. Rassili & A. Buhrig-Polaczek, Aachen Germany & Liege, Belgium, 2008

- ↑ Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, pp. 278–279

- ↑ Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, pp. 279–280

- 1 2 Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 280

- ↑ Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, pp. 280–281

- ↑ Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 281

- 1 2 Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 282

- 1 2 Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 284

- 1 2 Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 285

- 1 2 Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 287

- ↑ Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, pp. 285–286

- 1 2 3 Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 286

- ↑ Stefanescu 2008, p. 66.

- 1 2 3 Stefanescu 2008, p. 67.

- ↑ Porter, David A.; Easterling, K. E. (2000), Phase transformations in metals and alloys (2nd ed.), CRC Press, p. 236, ISBN 978-0-7487-5741-1.

- ↑ Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, pp. 286–288.

- 1 2 Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 288

- 1 2 3 4 5 Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 289

- 1 2 3 Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 290

- 1 2 Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, pp. 319–320.

- ↑ Iron and Steel Institute (1912), Journal of the Iron and Steel Institute, 86, Iron and Steel Institute, p. 547.

- ↑ Lesko, Jim (2007), Industrial design (2nd ed.), John Wiley and Sons, p. 39, ISBN 978-0-470-05538-0.

- ↑ Campbell, John (2004), Castings practice: the 10 rules of castings, Butterworth-Heinemann, pp. 69–71, ISBN 978-0-7506-4791-5.

- ↑ Blair & Stevens 1995, p. 4‐6.

- ↑ Kissell & Ferry 2002, p. 73.

Bibliography

- Blair, Malcolm; Stevens, Thomas L. (1995), Steel castings handbook (6th ed.), ASM International, ISBN 978-0-87170-556-3.

- Degarmo, E. Paul; Black, J T.; Kohser, Ronald A. (2003), Materials and Processes in Manufacturing (9th ed.), Wiley, ISBN 0-471-65653-4.

- Kalpakjian, Serope; Schmid, Steven (2006), Manufacturing Engineering and Technology (5th ed.), Pearson, ISBN 0-13-148965-8.

- Kissell, J. Randolph; Ferry, Robert L. (2002), Aluminum structures: a guide to their specifications and design (2nd ed.), John Wiley and Sons, ISBN 978-0-471-01965-7.

- Schleg, Frederick P.; Kohloff, Frederick H.; Sylvia, J. Gerin; American Foundry Society (2003), Technology of Metalcasting, American Foundry Society, ISBN 978-0-87433-257-5.

- Stefanescu, Doru Michael (2008), Science and Engineering of Casting Solidification (2nd ed.), Springer, ISBN 978-0-387-74609-8.

- Ravi, B (2010), Metal Casting: Computer-aided Design and Analysis (1st ed.), PHI, ISBN 81-203-2726-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Casting. |

- Interactive casting design/manufacturing examples

- Castings or Forgings? A look at the advantages of each manufacturing process

- Umha Aois – Bronze Age casting videoclip

- Viking Bronze – Early Medieval metal casting

- Video clip of a 50 gram arc cast alloy solidifying

- Glossary of Metalcasting Terms

- DoITPoMS Teaching and Learning Package- "Casting"

- Global Metal Casting Statistics