Aluminium

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of aluminium | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation |

UK: /ˌæljʊˈmɪniəm/ AL-yuu-MIN-ee-əm US: /əˈljuːmɪnəm/ ə-LEW-min-əm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative name | aluminum (US, informal) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | silvery gray metallic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aluminium in the periodic table | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 13 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group, period | group 13 (boron group), period 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Element category | post-transition metal, sometimes considered a metalloid | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight (Ar) | 26.9815385(7)[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ne] 3s2 3p1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase | solid | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 933.47 K (660.32 °C, 1220.58 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 2743 K (2470 °C, 4478 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density near r.t. | 2.70 g/cm3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid, at m.p. | 2.375 g/cm3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 10.71 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 284 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 24.20 J/(mol·K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | +3, +2,[2] +1[3], −1, −2 (an amphoteric oxide) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.61 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

1st: 577.5 kJ/mol 2nd: 1816.7 kJ/mol 3rd: 2744.8 kJ/mol (more) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 143 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 121±4 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 184 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Miscellanea | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure |

face-centered cubic (fcc)  | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | (rolled) 5000 m/s (at r.t.) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 23.1 µm/(m·K) (at 25 °C) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 237 W/(m·K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 28.2 nΩ·m (at 20 °C) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic[4] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic susceptibility (χmol) | +16.5·10−6 cm3/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young's modulus | 70 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 26 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 76 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.35 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 2.75 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vickers hardness | 160–350 MPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 160–550 MPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7429-90-5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prediction | Antoine Lavoisier[5] (1787) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery and first isolation | Hans Christian Ørsted[6] (1825) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Named by | Humphry Davy[5] (1807) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Main isotopes of aluminium | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Aluminium or aluminum (see below) is a chemical element with symbol Al and atomic number 13. It is a silvery-white, soft, nonmagnetic, ductile metal in the boron group. By mass, aluminium makes up about 8% of the Earth's crust; it is the third most abundant element after oxygen and silicon and the most abundant metal in the crust, though it is less common in the mantle below. Aluminium metal is so chemically reactive that native specimens are rare and limited to extreme reducing environments. Instead, it is found combined in over 270 different minerals.[7] The chief ore of aluminium is bauxite.

Aluminium is remarkable for the metal's low density and its ability to resist corrosion through the phenomenon of passivation. Aluminium and its alloys are vital to the aerospace industry[8] and important in transportation and building industries, such as building facades and window frames.[9] The oxides and sulfates are the most useful compounds of aluminium.[8]

Despite its prevalence in the environment, no known form of life uses aluminium salts metabolically, but aluminium is well tolerated by plants and animals.[10] Because of these salts' abundance, the potential for a biological role for them is of continuing interest, and studies continue.

Characteristics

Physical

Aluminium is a relatively soft, durable, lightweight, ductile, and malleable metal with appearance ranging from silvery to dull gray, depending on the surface roughness. It is nonmagnetic and does not easily ignite. A fresh film of aluminium serves as a good reflector (approximately 92%) of visible light and an excellent reflector (as much as 98%) of medium and far infrared radiation. The yield strength of pure aluminium is 7–11 MPa, while aluminium alloys have yield strengths ranging from 200 MPa to 600 MPa.[11] Aluminium has about one-third the density and stiffness of steel. It is easily machined, cast, drawn and extruded.

Aluminium atoms are arranged in a face-centered cubic (fcc) structure. Aluminium has a stacking-fault energy of approximately 200 mJ/m2.[12]

Aluminium is a good thermal and electrical conductor, having 59% the conductivity of copper, both thermal and electrical, while having only 30% of copper's density. Aluminium is capable of superconductivity, with a superconducting critical temperature of 1.2 kelvin and a critical magnetic field of about 100 gauss (10 milliteslas).[13] Aluminium is the most common material for the fabrication of superconducting qubits.[14]

Chemical

Corrosion resistance can be excellent because a thin surface layer of aluminium oxide forms when the bare metal is exposed to air, effectively preventing further oxidation,[15] in a process termed passivation. The strongest aluminium alloys are less corrosion resistant due to galvanic reactions with alloyed copper.[11] This corrosion resistance is greatly reduced by aqueous salts, particularly in the presence of dissimilar metals.

In highly acidic solutions, aluminium reacts with water to form hydrogen, and in highly alkaline ones to form aluminates— protective passivation under these conditions is negligible. Primarily because it is corroded by dissolved chlorides, such as common sodium chloride, household plumbing is never made from aluminium.[16]

However, because of its general resistance to corrosion, aluminium is one of the few metals that retains silvery reflectance in finely powdered form, making it an important component of silver-colored paints. Aluminium mirror finish has the highest reflectance of any metal in the 200–400 nm (UV) and the 3,000–10,000 nm (far IR) regions; in the 400–700 nm visible range it is slightly outperformed by tin and silver and in the 700–3000 nm (near IR) by silver, gold, and copper.[17]

Aluminium is oxidized by water at temperatures below 280 °C to produce hydrogen, aluminium hydroxide and heat:

- 2 Al + 6 H2O → 2 Al(OH)3 + 3 H2

This conversion is of interest for the production of hydrogen. However, commercial application of this fact has challenges in circumventing the passivating oxide layer, which inhibits the reaction, and in storing the energy required to regenerate the aluminium metal.[18]

Isotopes

Aluminium has many known isotopes, with mass numbers range from 21 to 42; however, only 27Al (stable) and 26Al (radioactive, t1⁄2 = 7.2×105 years) occur naturally. 27Al has a natural abundance above 99.9%. 26Al is produced from argon in the atmosphere by spallation caused by cosmic-ray protons. Aluminium isotopes are useful in dating marine sediments, manganese nodules, glacial ice, quartz in rock exposures, and meteorites. The ratio of 26Al to 10Be has been used to study transport, deposition, sediment storage, burial times, and erosion on 105 to 106 year time scales.[19] Cosmogenic 26Al was first applied in studies of the Moon and meteorites. Meteoroid fragments, after departure from their parent bodies, are exposed to intense cosmic-ray bombardment during their travel through space, causing substantial 26Al production. After falling to Earth, atmospheric shielding drastically reduces 26Al production, and its decay can then be used to determine the meteorite's terrestrial age. Meteorite research has also shown that 26Al was relatively abundant at the time of formation of our planetary system. Most meteorite scientists believe that the energy released by the decay of 26Al was responsible for the melting and differentiation of some asteroids after their formation 4.55 billion years ago.[20]

Natural occurrence

Stable aluminium is created when hydrogen fuses with magnesium, either in large stars or in supernovae.[21] It is estimated to be the 14th most common element in the Universe, by mass-fraction.[22] However, among the elements that have odd atomic numbers, aluminium is the third most abundant by mass fraction, after hydrogen and nitrogen.[22]

In the Earth's crust, aluminium is the most abundant (8.3% by mass) metallic element and the third most abundant of all elements (after oxygen and silicon).[23] The Earth's crust has a greater abundance of aluminium than the rest of the planet, primarily in aluminium silicates. In the Earth's mantle, which is only 2% aluminium by mass, these aluminium silicate minerals are largely replaced by silica and magnesium oxides. Overall, the Earth is about 1.4% aluminium by mass (eighth in abundance by mass). Aluminium occurs in greater proportion in the Earth than in the Solar system and Universe because the more common elements (hydrogen, helium, neon, nitrogen, carbon as hydrocarbon) are volatile at Earth's proximity to the Sun and large quantities of those were lost.

Because of its strong affinity for oxygen, aluminium is almost never found in the elemental state; instead it is found in oxides or silicates. Feldspars, the most common group of minerals in the Earth's crust, are aluminosilicates. Native aluminium metal can only be found as a minor phase in low oxygen fugacity environments, such as the interiors of certain volcanoes.[24] Native aluminium has been reported in cold seeps in the northeastern continental slope of the South China Sea. Chen et al. (2011)[25] propose the theory that these deposits resulted from bacterial reduction of tetrahydroxoaluminate Al(OH)4−.[25]

Aluminium also occurs in the minerals beryl, cryolite, garnet, spinel, and turquoise.[26] Impurities in Al2O3, such as chromium and iron, yield the gemstones ruby and sapphire, respectively.

Although aluminium is a common and widespread element, not all aluminium minerals are economically viable sources of the metal. Almost all metallic aluminium is produced from the ore bauxite (AlOx(OH)3–2x). Bauxite occurs as a weathering product of low iron and silica bedrock in tropical climatic conditions.[27] Bauxite is mined from large deposits in Australia, Brazil, Guinea, and Jamaica; it is also mined from lesser deposits in China, India, Indonesia, Russia, and Suriname.

Production and refinement

Bayer process and Hall–Héroult processes

Bauxite is converted to aluminium oxide (Al2O3) by the Bayer process.[10] Relevant chemical equations are:

- Al2O3 + 2 NaOH → 2 NaAlO2 + H2O

- 2 H2O + NaAlO2 → Al(OH)3 + NaOH

The intermediate, sodium aluminate, with the simplified formula NaAlO2, is soluble in strongly alkaline water, and the other components of the ore are not. Depending on the quality of the bauxite ore, twice as much waste ("Bauxite tailings") as alumina is generated.

The conversion of alumina to aluminium metal is achieved by the Hall–Héroult process. In this energy-intensive process, a solution of alumina in a molten (950 and 980 °C (1,740 and 1,800 °F)) mixture of cryolite (Na3AlF6) with calcium fluoride is electrolyzed to produce metallic aluminium:

- Al3+ + 3 e− → Al

The liquid aluminium metal sinks to the bottom of the solution and is tapped off, and usually cast into large blocks called aluminium billets for further processing. Carbon dioxide is produced at the carbon anode:

- 2 O2− + C → CO2 + 4 e−

The carbon anode is consumed by reaction with oxygen to form carbon dioxide gas, with a small quantity of fluoride gases. In modern smelters, the gas is filtered through alumina to remove fluorine compounds and return aluminium fluoride to the electrolytic cells. The anode (i.e. the reduction cell) must be replaced regularly, since it is consumed in the process. The cathode is also eroded, mainly by electrochemical processes and liquid metal movement induced by intense electrolytic currents. After five to ten years, depending on the current used in the electrolysis, a cell must be rebuilt because of cathode wear.

Aluminium electrolysis with the Hall–Héroult process consumes a lot of energy. The worldwide average specific energy consumption is approximately 15±0.5 kilowatt-hours per kilogram of aluminium produced (52 to 56 MJ/kg). Some smelters achieve approximately 12.8 kW·h/kg (46.1 MJ/kg). (Compare this to the heat of reaction, 31 MJ/kg, and the Gibbs free energy of reaction, 29 MJ/kg.) Minimizing line currents for older technologies are typically 100 to 200 kiloamperes; state-of-the-art smelters operate at about 350 kA.

The Hall–Heroult process produces aluminium with a purity of above 99%. Further purification can be done by the Hoopes process. This process involves the electrolysis of molten aluminium with a sodium, barium and aluminium fluoride electrolyte. The resulting aluminium has a purity of 99.99%.[10][28]

Electric power represents about 20% to 40% of the cost of producing aluminium, depending on the location of the smelter. Aluminium production consumes roughly 5% of electricity generated in the US.[29] Aluminium producers tend to locate smelters in places where electric power is both plentiful and inexpensive—such as the United Arab Emirates with its large natural gas supplies,[30] and Iceland[31] and Norway[32] with energy generated from renewable sources. The world's largest smelters of alumina are located in the People's Republic of China, Russia and the provinces of Quebec and British Columbia in Canada.[29][33][34]

In 2005, the People's Republic of China was the top producer of aluminium with almost a one-fifth world share, followed by Russia, Canada, and the US, reports the British Geological Survey.

Over the last 50 years, Australia has become the world's top producer of bauxite ore and a major producer and exporter of alumina (before being overtaken by China in 2007).[33][35] Australia produced 77 million tonnes of bauxite in 2013.[36] The Australian deposits have some refining problems, some being high in silica, but have the advantage of being shallow and relatively easy to mine.[37]

Aluminium chloride electrolysis process

The high energy consumption of Hall–Héroult process motivated the development of the electrolytic process based on aluminium chloride. The pilot plant with 6500 tons/year output was started in 1976 by Alcoa. The plant offered two advantages: (i) energy requirements were 40% less than plants using the Hall–Héroult process, and (ii) the more accessible kaolinite (instead of bauxite and cryolite) was used for feedstock. Nonetheless, the pilot plant was shut down. The reasons for failure were the cost of aluminium chloride, general technology maturity problems, and leakage of the trace amounts of toxic polychlorinated biphenyl compounds.[38][39]

Aluminium chloride process can also be used for the co-production of titanium, depending on titanium contents in kaolinite.

Aluminium carbothermic process

The non-electrolytic aluminium carbothermic process of aluminium production would theoretically be cheaper and consume less energy. However, it has been in the experimental phase for decades because the high operating temperature creates difficulties in material technology that have not yet been solved.[40][41]

Recycling

Aluminium is theoretically 100% recyclable without any loss of its natural qualities. According to the International Resource Panel's Metal Stocks in Society report, the global per capita stock of aluminium in use in society (i.e. in cars, buildings, electronics etc.) is 80 kg (180 lb). Much of this is in more-developed countries (350–500 kg (770–1,100 lb) per capita) rather than less-developed countries (35 kg (77 lb) per capita). Knowing the per capita stocks and their approximate lifespans is important for planning recycling.

Recovery of the metal through recycling has become an important task of the aluminium industry. Recycling was a low-profile activity until the late 1960s, when the growing use of aluminium beverage cans brought it to public awareness.

Recycling involves melting the scrap, a process that requires only 5% of the energy used to produce aluminium from ore, though a significant part (up to 15% of the input material) is lost as dross (ash-like oxide).[42] An aluminium stack melter produces significantly less dross, with values reported below 1%.[43] The dross can undergo a further process to extract aluminium.

Europe has achieved high rates of aluminium recycling ranging from 42% of beverage cans, 85% of construction materials, and 95% of transport vehicles.[44]

Recycled aluminium is known as secondary aluminium, but maintains the same physical properties as primary aluminium. Secondary aluminium is produced in a wide range of formats and is employed in 80% of alloy injections. Another important use is extrusion.

White dross from primary aluminium production and from secondary recycling operations still contains useful quantities of aluminium that can be extracted industrially.[45] The process produces aluminium billets, together with a highly complex waste material. This waste is difficult to manage. It reacts with water, releasing a mixture of gases (including, among others, hydrogen, acetylene, and ammonia), which spontaneously ignites on contact with air;[46] contact with damp air results in the release of copious quantities of ammonia gas. Despite these difficulties, the waste is used as a filler in asphalt and concrete.[47]

Compounds

Oxidation state +3

The vast majority of compounds, including all Al-containing minerals and all commercially significant aluminium compounds, feature aluminium in the oxidation state 3+. The coordination number of such compounds varies, but generally Al3+ is six-coordinate or tetracoordinate. Almost all compounds of aluminium(III) are colorless.[23]

Halides

All four trihalides are well known. Unlike the structures of the three heavier trihalides, aluminium fluoride (AlF3) features six-coordinate Al. The octahedral coordination environment for AlF3 is related to the compactness of the fluoride ion, six of which can fit around the small Al3+ center. AlF3 sublimes (with cracking) at 1,291 °C (2,356 °F). With heavier halides, the coordination numbers are lower. The other trihalides are dimeric or polymeric with tetrahedral Al centers. These materials are prepared by treating aluminium metal with the halogen, although other methods exist. Acidification of the oxides or hydroxides affords hydrates. In aqueous solution, the halides often form mixtures, generally containing six-coordinate Al centers that feature both halide and aquo ligands. When aluminium and fluoride are together in aqueous solution, they readily form complex ions such as [AlF(H

2O)

5]2+

, AlF

3(H

2O)

3, and [AlF

6]3−

. In the case of chloride, polyaluminium clusters are formed such as [Al13O4(OH)24(H2O)12]7+.

Oxide and hydroxides

Aluminium forms one stable oxide with the chemical formula Al2O3. It can be found in nature in the mineral corundum.[48] Aluminium oxide is also commonly called alumina.[49] Sapphire and ruby are impure corundum contaminated with trace amounts of other metals. The two oxide-hydroxides, AlO(OH), are boehmite and diaspore. There are three trihydroxides: bayerite, gibbsite, and nordstrandite, which differ in their crystalline structure (polymorphs). Most are produced from ores by a variety of wet processes using acid and base. Heating the hydroxides leads to formation of corundum. These materials are of central importance to the production of aluminium and are themselves extremely useful.

Carbide, nitride, and related materials

Aluminium carbide (Al4C3) is made by heating a mixture of the elements above 1,000 °C (1,832 °F). The pale yellow crystals consist of tetrahedral aluminium centers. It reacts with water or dilute acids to give methane. The acetylide, Al2(C2)3, is made by passing acetylene over heated aluminium.

Aluminium nitride (AlN) is the only nitride known for aluminium. Unlike the oxides, it features tetrahedral Al centers. It can be made from the elements at 800 °C (1,472 °F). It is air-stable material with a usefully high thermal conductivity. Aluminium phosphide (AlP) is made similarly; it hydrolyses to give phosphine:

- AlP + 3 H2O → Al(OH)3 + PH3

Organoaluminium compounds and related hydrides

A variety of compounds of empirical formula AlR3 and AlR1.5Cl1.5 exist.[50] These species usually feature tetrahedral Al centers formed by dimerization with some R or Cl bridging between both Al atoms, e.g. "trimethylaluminium" has the formula Al2(CH3)6 (see figure). With large organic groups, triorganoaluminium compounds exist as three-coordinate monomers, such as triisobutylaluminium. Such compounds are widely used in industrial chemistry, despite the fact that they are often highly pyrophoric. Few analogues exist between organoaluminium and organoboron compounds other than large organic groups.

The important aluminium hydride is lithium aluminium hydride (LiAlH4), which is used in as a reducing agent in organic chemistry. It can be produced from lithium hydride and aluminium trichloride:

- 4 LiH + AlCl3 → LiAlH4 + 3 LiCl

Several useful derivatives of LiAlH4 are known, e.g. sodium bis(2-methoxyethoxy)dihydridoaluminate. The simplest hydride, aluminium hydride or alane, remains a laboratory curiosity. It is a polymer with the formula (AlH3)n, in contrast to the corresponding boron hydride that is a dimer with the formula (BH3)2.

Oxidation states +1 and +2

Although the great majority of aluminium compounds feature Al3+ centers, compounds with lower oxidation states are known and sometime of significance as precursors to the Al3+ species.

Aluminium(I)

AlF, AlCl and AlBr exist in the gaseous phase when the trihalide is heated with aluminium. The composition AlI is unstable at room temperature, converting to triiodide:[51]

A stable derivative of aluminium monoiodide is the cyclic adduct formed with triethylamine, Al4I4(NEt3)4. Also of theoretical interest but only of fleeting existence are Al2O and Al2S. Al2O is made by heating the normal oxide, Al2O3, with silicon at 1,800 °C (3,272 °F) in a vacuum.[51] Such materials quickly disproportionate to the starting materials.

Aluminium(II)

Very simple Al(II) compounds are invoked or observed in the reactions of Al metal with oxidants. For example, aluminium monoxide, AlO, has been detected in the gas phase after explosion[52] and in stellar absorption spectra.[53] More thoroughly investigated are compounds of the formula R4Al2 which contain an Al-Al bond and where R is a large organic ligand.[54]

Analysis

The presence of aluminium can be detected in qualitative analysis using aluminon.

Applications

General use

Aluminium is the most widely used non-ferrous metal.[55] The global production of aluminium in 2005 was 31.9 million tonnes. It exceeded that of any other metal except iron (837.5 million tonnes).[56]

Aluminium is almost always alloyed, which markedly improves its mechanical properties, especially when tempered. For example, the common aluminium foils and beverage cans are alloys of 92% to 99% aluminium.[57] The main alloying agents are copper, zinc, magnesium, manganese, and silicon (e.g., duralumin) with the levels of other metals in a few percent by weight.[58]

Some of the many uses for aluminium metal are in:

- Transportation[59] (automobiles, aircraft, trucks, railway cars, marine vessels, bicycles, spacecraft, etc.) as sheet, tube, and castings.

- Packaging[60] (cans, foil, frame of etc.).

- Food and beverage containers, because of its resistance to corrosion.

- Construction (windows, doors, siding, building wire, sheathing, roofing, etc.).[61]

- A wide range of household items, from cooking utensils to baseball bats and watches.[62]

- Street lighting poles,[63] sailing ship masts, walking poles.

- Outer shells and cases for consumer electronics and photographic equipment.

- Electrical transmission lines for power distribution ("creep" and oxidation are not issues in this application as the terminations are usually multi-sided "crimps" which enclose all sides of the conductor with a gas-tight seal).

- MKM steel and Alnico magnets.

- Super purity aluminium (SPA, 99.980% to 99.999% Al), used in electronics and CDs, and also in wires/cabling.

- Heat sinks for transistors, CPUs, and other components in electronic appliances.

- Substrate material of metal-core copper clad laminates used in high brightness LED lighting.

- Light reflective surfaces and paint.

- Pyrotechnics, solid rocket fuels, and thermite.

- Production of hydrogen gas by reaction with hydrochloric acid or sodium hydroxide.

- In alloy with magnesium to make aircraft bodies and other transportation components.

- Cooking utensils, because of its resistance to corrosion and light-weight.[64]

- Coins in such countries as France, Italy, Poland, Finland, Romania, Israel, and the former Yugoslavia struck from aluminium or an aluminium-copper alloy.[65][66]

- Musical instruments. Some guitar models sport aluminium diamond plates on the surface of the instruments, usually either chrome or black. Kramer Guitars and Travis Bean are both known for having produced guitars with necks made of aluminium, which gives the instrument a very distinctive sound. Aluminium is used to make some guitar resonators and some electric guitar speakers.[67]

Aluminium is usually alloyed – it is used as pure metal only when corrosion resistance and/or workability is more important than strength or hardness. The strength of aluminium alloys is abruptly increased with small additions of scandium, zirconium, or hafnium.[68] A thin layer of aluminium can be deposited onto a flat surface by physical vapor deposition or (very infrequently) chemical vapor deposition or other chemical means to form optical coatings and mirrors.

Aluminium compounds

Because aluminium is abundant and most of its derivatives exhibit low toxicity, the compounds of aluminium enjoy wide and sometimes large-scale applications.

Alumina

Aluminium oxide (Al2O3) and the associated oxy-hydroxides and trihydroxides are produced or extracted from minerals on a large scale. The great majority of this material is converted to metallic aluminium. In 2013, about 10% of the domestic shipments in the United States were used for other applications.[69] One major use is to absorb water where it is viewed as a contaminant or impurity. Alumina is used to remove water from hydrocarbons in preparation for subsequent processes that would be poisoned by moisture.

Aluminium oxides are common catalysts for industrial processes; e.g. the Claus process to convert hydrogen sulfide to sulfur in refineries and to alkylate amines. Many industrial catalysts are "supported" by alumina, meaning that the expensive catalyst material (e.g., platinum) is dispersed over a surface of the inert alumina.

Being a very hard material (Mohs hardness 9), alumina is widely used as an abrasive; being extraordinarily chemically inert, it is useful in highly reactive environments such as high pressure sodium lamps.

Sulfates

Several sulfates of aluminium have industrial and commercial application. Aluminium sulfate (Al2(SO4)3·(H2O)18) is produced on the annual scale of several billions of kilograms. About half of the production is consumed in water treatment. The next major application is in the manufacture of paper. It is also used as a mordant, in fire extinguishers, in fireproofing, as a food additive (E number E173), and in leather tanning. Aluminium ammonium sulfate, which is also called ammonium alum, (NH4)Al(SO4)2·12H2O, is used as a mordant and in leather tanning,[70] as is aluminium potassium sulfate ([Al(K)](SO4)2)·(H2O)12. The consumption of both alums is declining.

Chlorides

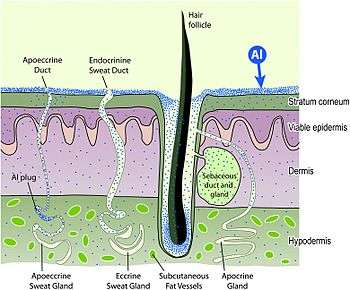

Aluminium chloride (AlCl3) is used in petroleum refining and in the production of synthetic rubber and polymers. Although it has a similar name, aluminium chlorohydrate has fewer and very different applications, particularly as a colloidal agent in water purification and an antiperspirant. It is an intermediate in the production of aluminium metal.

Niche compounds

Many aluminium compounds have niche applications:

- Aluminium acetate in solution is used as an astringent.[71]

- Aluminium borate (Al2O3·B2O3) and aluminium fluorosilicate (Al2(SiF6)3) are used in the production of glass, ceramics, synthetic gemstones.

- Aluminium phosphate (AlPO4) used in the manufacture of glass, ceramic, pulp and paper products, cosmetics, paints, varnishes, and in dental cement.[72]

- Aluminium hydroxide (Al(OH)3) is used as an antacid, and mordant; it is used also in water purification, the manufacture of glass and ceramics, and in the waterproofing fabrics.

- Lithium aluminium hydride is a powerful reducing agent used in organic chemistry.

- Organoaluminiums are used as Lewis acids and cocatalysts.

- Methylaluminoxane is a cocatalyst for Ziegler-Natta olefin polymerization to produce vinyl polymers such as polyethene.

- Aqueous aluminium ions (such as aqueous aluminium sulfate) are used to treat against fish parasites such as Gyrodactylus salaris.

- In many vaccines, certain aluminium salts serve as an immune adjuvant (immune response booster) to allow the protein in the vaccine to achieve sufficient potency as an immune stimulant.

Aluminium alloys in structural applications

Aluminium alloys with a wide range of properties are used in engineering structures. Alloy systems are classified by a number system (ANSI) or by names indicating their main alloying constituents (DIN and ISO).

The strength and durability of aluminium alloys vary widely, not only as a result of the components of the specific alloy, but also as a result of heat treatments and manufacturing processes. A lack of knowledge of these aspects has from time to time led to improperly designed structures and gained aluminium a bad reputation.

One important structural limitation of aluminium alloys is their fatigue strength. Unlike steels, aluminium alloys have no well-defined fatigue limit, meaning that fatigue failure eventually occurs, under even very small cyclic loadings. Engineers must assess applications and design for a fixed and finite life of the structure, rather than infinite life.

Another important property of aluminium alloys is sensitivity to heat. Workshop procedures are complicated by the fact that aluminium, unlike steel, melts without first glowing red. Manual blow torch operations require additional skill and experience. Aluminium alloys, like all structural alloys, are subject to internal stresses after heat operations such as welding and casting. The lower melting points of aluminium alloys make them more susceptible to distortions from thermally induced stress relief. Stress can be relieved and controlled during manufacturing by heat-treating the parts in an oven, followed by gradual cooling—in effect annealing the stresses.

The low melting point of aluminium alloys has not precluded use in rocketry, even in combustion chambers where gases can reach 3500 K. The Agena upper stage engine used regeneratively cooled aluminium in some parts of the nozzle, including the thermally critical throat region.

Another alloy of some value is aluminium bronze (Cu-Al alloy).

History

Although ancient Greeks and Romans used aluminium salts as dyeing mordants and as astringents for dressing wounds, metallic aluminium was not refined until the modern era. Alum, a salt of aluminium and potassium, is still used as a styptic. In 1782, Guyton de Morveau suggested calling the "base" of (i.e., the metallic element in) alum alumine.[73] In 1808, Humphry Davy identified the existence of a metal base of alum, which he at first termed alumium and later aluminum (see etymology section, below).

The metal was first produced in 1825 in an impure form by Danish physicist and chemist Hans Christian Ørsted. He reacted anhydrous aluminium chloride with potassium amalgam, yielding a lump of metal looking similar to tin.[74][75] Friedrich Wöhler was aware of these experiments and cited them, but after repeating Ørsted's experiments, he concluded that this metal was pure potassium. He conducted a similar experiment in 1827 by mixing anhydrous aluminium chloride with potassium and produced aluminium.[75] Wöhler is therefore generally credited with isolating aluminium (Latin alumen, alum). Further, Pierre Berthier discovered aluminium in bauxite ore. Henri Etienne Sainte-Claire Deville improved Wöhler's method in 1846. As described in his 1859 book, aluminium trichloride could be reduced by sodium, which was more convenient and less expensive than potassium, which Wöhler had used.[76] In the mid-1880s, aluminium metal was exceedingly difficult to produce, which made pure aluminium more valuable than gold.[77] So celebrated was the metal that bars of aluminium were exhibited at the Exposition Universelle of 1855.[78] Napoleon III of France is reputed to have held a banquet where the most honored guests were given aluminium utensils, while the others made do with gold.[79][80]

Aluminium was selected as the material for the 100 ounces (2.8 kg) capstone of the Washington Monument in 1884, a time when one ounce (30 grams) cost the daily wage of a common worker on the project (in 1884 about $1 for 10 hours of labor.[81] The capstone, which was set in place on 6 December 1884 in an elaborate dedication ceremony, was the largest single piece of aluminium cast at the time.[81][82] It suffered some damage from lightning strikes, and was reengineered, redesigned and replaced in the 1934 renovation of the monument.[81]

The Cowles companies supplied aluminium alloy in quantity in the United States and England using smelters like the furnace of Carl Wilhelm Siemens by 1886.[83][84][85]

Hall-Heroult process: availability of cheap aluminium metal

Charles Martin Hall of Ohio in the US and Paul Héroult of France independently developed the Hall-Héroult electrolytic process that facilitated large-scale production of metallic aluminium. This process remains in use today.[86] In 1888, with the financial backing of Alfred E. Hunt, the Pittsburgh Reduction Company started; today it is known as Alcoa. Héroult's process was in production by 1889 in Switzerland at Aluminium Industrie, now Alcan, and at British Aluminium, now Luxfer Group and Alcoa, by 1896 in Scotland.[87]

By 1895, the metal was being used as a building material as far away as Sydney, Australia, in the dome of the Chief Secretary's Building.

With the explosive expansion of the airplane industry during World War I (1914–1917), major governments demanded large shipments of aluminium for light, strong airframes. They often subsidized factories and the necessary electrical supply systems.[88]

Many navies have used an aluminium superstructure for their vessels; the 1975 fire aboard USS Belknap that gutted her aluminium superstructure, as well as observation of battle damage to British ships during the Falklands War, led to many navies switching to all steel superstructures.

Aluminium wire was once widely used for domestic electrical wiring in the United States, and a number of fires resulted from creep and corrosion-induced failures at junctions and terminations; additional and preventable factors in the failures have been identified.[89][90] Aluminium is still used in electrical services with specially designed wire termination hardware.

Etymology

The various names all derive from its elemental presence in alum. The word comes into English from Old French, from alumen, a Latin word meaning "bitter salt".[91]

Two variants of the name are in current use: aluminium ( /ˌæljʊˈmɪniəm/) and aluminum (/əˈluːmɪnəm/). There is also an obsolete variant alumium. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) adopted aluminium as the standard international name for the element in 1990 but, three years later, recognized aluminum as an acceptable variant. The IUPAC periodic table uses the aluminium spelling only.[92] IUPAC internal publications use the two spelling with nearly equal frequency.[93]

Different endings

Most countries use the ending "-ium" for "aluminium". In the United States and Canada, the ending "-um" predominates.[23][94] The Canadian Oxford Dictionary prefers aluminum, whereas the Australian Macquarie Dictionary prefers aluminium. In 1926, the American Chemical Society officially decided to use aluminum in its publications; American dictionaries typically label the spelling aluminium as "chiefly British".[95][96] The earliest citation given in the Oxford English Dictionary for any word used as a name for this element is alumium, which British chemist and inventor Humphry Davy employed in 1808 for the metal he was trying to isolate electrolytically from the mineral alumina. The citation is from the journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London: "Had I been so fortunate as to have obtained more certain evidences on this subject, and to have procured the metallic substances I was in search of, I should have proposed for them the names of silicium, alumium, zirconium, and glucium."[97][98]

Davy settled on aluminum by the time he published his book Elements of Chemical Philosophy in June 1812: "This substance appears to contain a peculiar metal, but as yet Aluminum has not been obtained in a perfectly free state, though alloys of it with other metalline substances have been procured sufficiently distinct to indicate the probable nature of alumina."[99] In September 1812, fellow British scientist Thomas Young[100] wrote a review of Davy's book, which was published anonymously in the Quarterly Review, a British literary and political periodical, in which he objected to aluminum and proposed the name aluminium: "for so we shall take the liberty of writing the word, in preference to aluminum, which has a less classical sound."[101]

The -ium suffix followed the precedent set in other newly discovered elements of the time: potassium, sodium, magnesium, calcium, and strontium (all of which Davy isolated himself). Nevertheless, element names ending in -um were not unknown at the time; for example, platinum (known to Europeans since the 16th century), molybdenum (discovered in 1778), and tantalum (discovered in 1802). The -um suffix is consistent with the universal spelling alumina for the oxide (as opposed to aluminia), as lanthana is the oxide of lanthanum, and magnesia, ceria, and thoria are the oxides of magnesium, cerium, and thorium respectively.

The aluminum spelling is used in the Webster's Dictionary of 1828. In his advertising handbill for his new electrolytic method of producing the metal in 1892, Charles Martin Hall used the -um spelling, despite his constant use of the -ium spelling in all the patents[86] he filed between 1886 and 1903. Hall's domination of production of the metal ensured that aluminum became the standard English spelling in North America.

Biology

Despite its widespread occurrence in the Earth crust, aluminium has no known function in biology. Aluminium salts are remarkably nontoxic, aluminium sulfate having an LD50 of 6207 mg/kg (oral, mouse), which corresponds to 500 grams for an 80 kg (180 lb) person.[10] The extremely low acute toxicity notwithstanding, the health effects of aluminium are of interest in view of the widespread occurrence of the element in the environment and in commerce.

Health concerns

In very high doses, aluminium is associated with altered function of the blood–brain barrier.[103] A small percentage of people are allergic to aluminium and experience contact dermatitis, digestive disorders, vomiting or other symptoms upon contact or ingestion of products containing aluminium, such as antiperspirants and antacids. In those without allergies, aluminium is not as toxic as heavy metals, but there is evidence of some toxicity if it is consumed in amounts greater than 40 mg/day per kg of body mass.[104] The use of aluminium cookware has not been shown to lead to aluminium toxicity in general, however excessive consumption of antacids containing aluminium compounds and excessive use of aluminium-containing antiperspirants provide more significant exposure levels. Consumption of acidic foods or liquids with aluminium enhances aluminium absorption,[105] and maltol has been shown to increase the accumulation of aluminium in nerve and bone tissues.[106] Aluminium increases estrogen-related gene expression in human breast cancer cells cultured in the laboratory.[107] The estrogen-like effects of these salts have led to their classification as metalloestrogens.

There is little evidence that aluminium in antiperspirants causes skin irritation.[10] Nonetheless, its occurrence in antiperspirants, dyes (such as aluminium lake), and food additives has caused concern.[108] Although there is little evidence that normal exposure to aluminium presents a risk to healthy adults,[109] some studies point to risks associated with increased exposure to the metal.[108] Aluminium in food may be absorbed more than aluminium from water.[110] It is classified as a non-carcinogen by the US Department of Health and Human Services.[104]

In case of suspected sudden intake of a large amount of aluminium, deferoxamine mesylate may be given to help eliminate it from the body by chelation.[111]

Occupational safety

Exposure to powdered aluminium or aluminium welding fumes can cause pulmonary fibrosis. The United States Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has set a permissible exposure limit of 15 mg/m3 time weighted average (TWA) for total exposure and 5 mg/m3 TWA for respiratory exposure. The US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) recommended exposure limit is the same for respiratory exposure but is 10 mg/m3 for total exposure, and 5 mg/m3 for fumes and powder.

Fine aluminium powder can ignite or explode, posing another workplace hazard.[112][113]

Alzheimer's disease

Aluminium has controversially been implicated as a factor in Alzheimer's disease.[114] According to the Alzheimer's Society, the medical and scientific opinion is that studies have not convincingly demonstrated a causal relationship between aluminium and Alzheimer's disease.[115] Nevertheless, some studies, such as those on the PAQUID cohort,[116] cite aluminium exposure as a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease. Some brain plaques have been found to contain increased levels of the metal.[117] Research in this area has been inconclusive; aluminium accumulation may be a consequence of the disease rather than a causal agent.[118][119]

Effect on plants

Aluminium is primary among the factors that reduce plant growth on acid soils. Although it is generally harmless to plant growth in pH-neutral soils, the concentration in acid soils of toxic Al3+ cations increases and disturbs root growth and function.[120][121][122][123]

Most acid soils are saturated with aluminium rather than hydrogen ions. The acidity of the soil is therefore, a result of hydrolysis of aluminium compounds.[124] The concept of "corrected lime potential"[125] is now used to define the degree of base saturation in soil testing to determine the "lime requirement".[126][127]

Wheat has developed a tolerance to aluminium, releasing organic compounds that bind to harmful aluminium cations. Sorghum is believed to have the same tolerance mechanism. The first gene for aluminium tolerance has been identified in wheat. It was shown that sorghum's aluminium tolerance is controlled by a single gene, as for wheat.[128] This adaptation is not found in all plants.

Biodegradation

A Spanish scientific report from 2001 claimed that the fungus Geotrichum candidum consumes the aluminium in compact discs.[129][130] Other reports all refer back to the 2001 Spanish report and there is no supporting original research. Better documented, the bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the fungus Cladosporium resinae are commonly detected in aircraft fuel tanks that use kerosene-based fuels (not AV gas), and laboratory cultures can degrade aluminium.[131] However, these life forms do not directly attack or consume the aluminium; rather, the metal is corroded by microbe waste products.[132]

See also

References

- ↑ Meija, J.; et al. (2016). "Atomic weights of the elements 2013 (IUPAC Technical Report)". Pure Appl. Chem. 88 (3): 265–91. doi:10.1515/pac-2015-0305.

- ↑ Aluminium monoxide

- ↑ Aluminium iodide

- ↑ Lide, D. R. (2000). "Magnetic susceptibility of the elements and inorganic compounds" (PDF). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (81st ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 0849304814.

- 1 2 "Aluminum". Los Alamos National Laboratory. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ↑ "13 Aluminium". Elements.vanderkrogt.net. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- ↑ Shakhashiri, B. Z. (17 March 2008). "Chemical of the Week: Aluminum" (PDF). SciFun.org. University of Wisconsin. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 May 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- 1 2 Singh, Bikram Jit (2014). RSM: A Key to Optimize Machining: Multi-Response Optimization of CNC Turning with Al-7020 Alloy. Anchor Academic Publishing (aap_verlag). ISBN 9783954892099.

- ↑ Hihara, Lloyd H.; Adler, Ralph P. I.; Latanision, Ronald M. (2013-10-23). Environmental Degradation of Advanced and Traditional Engineering Materials. CRC Press. ISBN 9781439819272.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Frank, W. B. (2009). "Aluminum". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a01_459.pub2.

- 1 2 Polmear, I. J. (1995). Light Alloys: Metallurgy of the Light Metals (3rd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-340-63207-9.

- ↑ Dieter, G. E. (1988). Mechanical Metallurgy. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-016893-8.

- ↑ Cochran, J. F.; Mapother, D. E. (1958). "Superconducting Transition in Aluminum". Physical Review. 111 (1): 132–142. Bibcode:1958PhRv..111..132C. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.111.132.

- ↑ Devoret, M. H.; Schoelkopf, R. J. (2013). "Superconducting Circuits for Quantum Information: An Outlook". Science. 339 (6124): 1169–1174. doi:10.1126/science.1231930.

- ↑ Vargel, Christian (2004) [French edition published 1999]. Corrosion of Aluminium. Elsevier. ISBN 0-08-044495-4. Archived from the original on 21 May 2016.

- ↑ Beal, Roy E. (1 January 1999). Engine Coolant Testing : Fourth Volume. ASTM International. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-8031-2610-7. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016.

- ↑ Macleod, H. A. (2001). Thin-film optical filters. CRC Press. pp. 158–159. ISBN 0-7503-0688-2.

- ↑ "Reaction of Aluminum with Water to Produce Hydrogen" (PDF). U.S. Department of Energy. 1 January 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 September 2012.

- ↑ Dickin, A. P. (2005). "In situ Cosmogenic Isotopes". Radiogenic Isotope Geology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53017-0. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008.

- ↑ Dodd, R. T. (1986). Thunderstones and Shooting Stars. Harvard University Press. pp. 89–90. ISBN 0-674-89137-6.

- ↑ Cameron, A. G. W. (1957). Stellar Evolution, Nuclear Astrophysics, and Nucleogenesis (PDF) (2nd ed.). Atomic Energy of Canada. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 January 2016.

- 1 2 Abundance in the Universe for all the elements in the Periodic Table Archived 11 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine.. Periodictable.com. Retrieved on 30 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 217. ISBN 0-08-037941-9.

- ↑ Barthelmy, D. "Aluminum Mineral Data". Mineralogy Database. Archived from the original on 4 July 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- 1 2 Chen, Z.; Huang, Chi-Yue; Zhao, Meixun; Yan, Wen; Chien, Chih-Wei; Chen, Muhong; Yang, Huaping; Machiyama, Hideaki; Lin, Saulwood (2011). "Characteristics and possible origin of native aluminum in cold seep sediments from the northeastern South China Sea". Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 40 (1): 363–370. Bibcode:2011JAESc..40..363C. doi:10.1016/j.jseaes.2010.06.006.

- ↑ Downs, A. J. (1993-05-31). Chemistry of Aluminium, Gallium, Indium and Thallium. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9780751401035.

- ↑ Guilbert, J. F.; Park, C. F. (1986). The Geology of Ore Deposits. W. H. Freeman. pp. 774–795. ISBN 0-7167-1456-6.

- ↑ Totten, G. E.; Mackenzie, D. S. (2003). Handbook of Aluminum. Marcel Dekker. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-8247-4843-2. Archived from the original on 15 June 2016.

- 1 2 Emsley, J. (2001). "Aluminium". Nature's Building Blocks: An A–Z Guide to the Elements. Oxford University Press. p. 24. ISBN 0-19-850340-7.

- ↑ Dipaola, Anthony (4 June 2013). "U.A.E. Plans to Merge Aluminum Makers in $15 Billion Venture". bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Hilmarsson, Thorsteinn. "Energy and aluminium in Iceland" (PDF). institutenorth.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "From alumina to aluminium". hydro.com. Archived from the original on 14 June 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- 1 2 Brown, T. J. (2009). World Mineral Production 2003–2007. British Geological Survey.

- ↑ Schmitz, C.; Domagala, J.; Haag, P. (2006). Handbook of Aluminium Recycling. Vulkan-Verlag. p. 27. ISBN 3-8027-2936-6.

- ↑ "The Australian Industry". Australian Aluminium Council. Archived from the original on 17 July 2007. Retrieved 11 August 2007.

- ↑ "Bauxite and Alumina, US Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries" (PDF). USGS. February 2014. p. 26. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ↑ "Australian Bauxite". Australian Aluminium Council. Archived from the original on 18 July 2007. Retrieved 11 August 2007.

- ↑ Kannan, G.N.; Desikan, P.S. (1985). "Critical appraisal and review of aluminium chloride electrolysis for the production of aluminium" (PDF). Bulletin of Electrochemistry. 1 (5): 483–488. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 December 2015.

- ↑ Green, John A. S. (2007). Aluminum Recycling and Processing for Energy Conservation and Sustainability. ASM International. p. 197. ISBN 1615030573.

- ↑ Aluminum Carbothermic Technology Advanced Reactor Process Archived 24 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine.. US Department of Energy

- ↑ Balomenos, Efthymios (June 2011). "Carbothermic reduction of alumina: A review of developed processes and novel concepts" (PDF). European Metallurgical Conference (EMC-2011). 3: 729–743. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 December 2015.

- ↑ "Benefits of Recycling". Ohio Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original on 24 June 2003.

- ↑ "Theoretical/Best Practice Energy Use In Metalcasting Operations" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 October 2013.

- ↑ "Reciclado del aluminio. Confemetal.es ASERAL" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 20 July 2011.

- ↑ Hwang, J. Y.; Huang, X.; Xu, Z. (2006). "Recovery of Metals from Aluminium Dross and Salt cake" (PDF). Journal of Minerals & Materials Characterization & Engineering. 5 (1): 47. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 September 2012.

- ↑ "Why are dross & saltcake a concern?". www.experts123.com. Archived from the original on 14 November 2012.

- ↑ Dunster, A. M.; et al. (2005). "Added value of using new industrial waste streams as secondary aggregates in both concrete and asphalt". Waste & Resources Action Programme.

- ↑ Roscoe, Henry Enfield; Schorlemmer, Carl (1913). A treatise on chemistry. Macmillan.

- ↑ Eastaugh, Nicholas; Walsh, Valentine; Chaplin, Tracey; Siddall, Ruth (2008-09-10). Pigment Compendium. Routledge. ISBN 9781136373930.

- ↑ Elschenbroich, C. (2006). Organometallics. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-29390-2.

- 1 2 Dohmeier, C.; Loos, D.; Schnöckel, H. (1996). "Aluminum(I) and Gallium(I) Compounds: Syntheses, Structures, and Reactions". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 35 (2): 129–149. doi:10.1002/anie.199601291.

- ↑ Tyte, D. C. (1964). "Red (B2Π–A2σ) Band System of Aluminium Monoxide". Nature. 202 (4930): 383–384. Bibcode:1964Natur.202..383T. doi:10.1038/202383a0.

- ↑ Merrill, P. W.; Deutsch, A. J.; Keenan, P. C. (1962). "Absorption Spectra of M-Type Mira Variables". The Astrophysical Journal. 136: 21. Bibcode:1962ApJ...136...21M. doi:10.1086/147348.

- ↑ Uhl, W. (2004). "Organoelement Compounds Possessing Al—Al, Ga—Ga, In—In, and Tl—Tl Single Bonds". Advances in Organometallic Chemistry. Advances in Organometallic Chemistry. 51: 53–108. ISBN 0-12-031151-8. doi:10.1016/S0065-3055(03)51002-4.

- ↑ "Aluminum". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- ↑ Hetherington, L. E. (2007). World Mineral Production: 2001–2005. British Geological Survey. ISBN 978-0-85272-592-4.

- ↑ Millberg, L. S. "Aluminum Foil". How Products are Made. Archived from the original on 13 July 2007. Retrieved 11 August 2007.

- ↑ Lyle, J. P.; Granger, D. A.; Sanders, R. E. (2005). "Aluminum Alloys". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a01_481.

- ↑ Davis, Joseph R. (1993). Aluminum and Aluminum Alloys. ASM International. ISBN 9780871704962.

- ↑ Selke, Susan (1994-04-21). Packaging and the Environment: Alternatives, Trends and Solutions. CRC Press. ISBN 9781566761048.

- ↑ "Sustainability of Aluminium in Buildings" (PDF). European Aluminium Association. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- ↑ "Materials in Watchmaking – From Traditional to Exotic". Watches. Infoniac.com. Archived from the original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ↑ Brown, Richard E. (2008-09-09). Electric Power Distribution Reliability, Second Edition. CRC Press. ISBN 9780849375682.

- ↑ Ghali, Edward (2010-05-05). Corrosion Resistance of Aluminum and Magnesium Alloys: Understanding, Performance, and Testing. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470531761.

- ↑ "World's coinage uses 24 chemical elements, Part 1". World Coin News. 17 February 1992.

- ↑ "World's coinage uses 24 chemical elements, Part 2". World Coin News. 2 March 1992.

- ↑ "What is the difference between paper-cone and aluminum-cone woofers in your bass guitar speaker cabinets? – MUSIC Group. All rights reserved.". musicgroup-prod.mindtouch.us. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ↑ Skachkov, V. M.; Pasechnik, L. A.; Yatsenko, S. P. (2014). "Introduction of scandium, zirconium and hafnium into aluminum alloys. Dispersion hardening of intermetallic compounds with nanodimensional particles" (PDF). Nanosystems: physics, chemistry, mathematics. 5 (4). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ↑ "Minerals Yearbook Bauxite and Alumina" (PDF). USGS. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ Helmboldt, O. (2007). "Aluminum Compounds, Inorganic". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a01_527.pub2.

- ↑ Ryan, Rachel S. M.; Organization, World Health (2004). WHO Model Formulary, 2004. World Health Organization. ISBN 9789241546317.

- ↑ Occupational Skin Disease. Grune & Stratton. 1983. ISBN 9780808914945.

- ↑ de Morveau (1782) "Mémoire sur les dénominations chimiques, la nécessité d'en perfectionner le système, & les règles pour y parvenir" (Memoir on chemical names, the necessity of improving the system, and rules for attaining it), Observations sur la physique, sur l'histoire naturelle, et sur les arts, …, 19 : 370–382 ; see especially p. 378. From p. 378: "La seconde terre est celle qui sert de base à l'alun: en la nommant argille, il faudroit chercher un autre nom au minéral, qui n'en recèle jamais qu'une portion; il faudroit, suivant notre second principe, substituer le mot argilleux au mot alumineux, pour tous ses composés. Il est plus simple de conserver le dernier, & en tirer un substantif, pour indiquer l'étre primitif. Ainsi, l'on dira que l'alun ou vitriol alumineux a pour base l'alumine, que la Nature nous offre abondamment dans les argilles." (The second earth is what serves as the base in alum: by naming it "clay", one would have to seek another name for the mineral, which never harbors even a part of it; one would have to, following our second principle [for naming chemical compounds], substitute the word "clay-ish" for the word "aluminous" in all its compounds. It is simpler to retain the latter and to draw a noun from it, in order to indicate the primitive entity [i.e., element]. Thus, one will say that alum or aluminous sulfate has as [its] base alumine [i.e., aluminium], which Nature offers us abundantly in clays.)

- ↑ Ørsted (1827) "Fra 31 Maj 1824 til 31 Maj 1825" ([Proceedings of the Society] from 31 May 1824 until 31 May 1825), Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskabs, Philosophiske og Historiske Afhandlinger (The Royal Danish Scientific Society, Philosophical and Historical Papers), 3 : xxv–xxvi. Archived 15 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Ørsted produced aluminium chloride (Chlorleeræret, chloride of clay ore) by passing chlorine over heated clay (Leer), and then reacted it with potassium amalgam (Kaliamalgam), which mixture, after distillation, left a lump of metal (Metalklump) resembling tin (Tinnet), which he called "clay metal" (Leermetal).

- 1 2 Wöhler, F. (1827). "Ueber das Aluminium". Annalen der Physik und Chemie. 2nd series. 11: 146–161.

- ↑ Sainte-Claire Deville, H. E. (1859). De l'aluminium, ses propriétés, sa fabrication. Paris: Mallet-Bachelier. Archived from the original on 30 April 2016.

- ↑ Polmear, I. J. (2006). "Production of Aluminium". Light Alloys from Traditional Alloys to Nanocrystals. Elsevier/Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-0-7506-6371-7.

- ↑ Karmarsch, C. (1864). "Fernerer Beitrag zur Geschichte des Aluminiums". Polytechnisches Journal. 171 (1): 49.

- ↑ Venetski, S. (1969). ""Silver" from clay". Metallurgist. 13 (7): 451–453. doi:10.1007/BF00741130.

- ↑ "Friedrich Wohler's Lost Aluminum". ChemMatters: 14. October 1990.

- 1 2 3 Binczewski, G. J. (1995). "The Point of a Monument: A History of the Aluminum Cap of the Washington Monument". JOM. 47 (11): 20–25. Bibcode:1995JOM....47k..20B. doi:10.1007/BF03221302. Archived from the original on 24 January 2016.

- ↑ Kelly, John (19 June 2013). "Local: The Washington Monument is tall, but is it the tallest?". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ↑ "Cowles' Aluminium Alloys". The Manufacturer and Builder. 18 (1): 13. 1886. Archived from the original on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- ↑ McMillan, W. G. (1891). A Treatise on Electro-Metallurgy. London: Charles Griffin and Company, Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company. pp. 302–305. Retrieved 26 October 2007.

- ↑ Sackett, W. E.; Scannell, J. J.; Watson, M. E. (1917). Scannel's New Jersey's First Citizens and State Guide. J.J. Scannell. pp. 103–105. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- 1 2 US patent 400664, Charles Martin Hall, "Process of Reducing Aluminium from its Fluoride Salts by Electrolysis", issued 2 April 1889

- ↑ Wallace, D. H. (1977) [1937]. Market Control in the Aluminum Industry (Reprint ed.). Arno Press. p. 6. ISBN 0-405-09786-7.

- ↑ Ingulstad, Mats (2012) "'We Want Aluminum, No Excuses': Business-Government Relations in the American Aluminum Industry, 1917–1957," pp. 33–68 in From Warfare to Welfare: Business-Government Relations in the Aluminium Industry, ed. Mats Ingulstad and Hans Otto Frøland. Oslo: Tapir Academic Press, 2012.

- ↑ Home Inspection and Building Inspection: The Hazards of Aluminum Wiring. Heimer.com. Retrieved on 30 July 2016.

- ↑ Aluminum wiring Archived 6 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine.. Faqs.org (27 March 2014). Retrieved on 30 July 2016.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "alum". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 30 November 2016. Retrieved 2016-11-18.. iupac.org

- ↑ IUPAC Web site publication search for 'aluminum'. google.com

- ↑ Bremner, John Words on Words: A Dictionary for Writers and Others Who Care about Words, pp. 22–23. ISBN 0-231-04493-3.

- ↑ "Aluminium – Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary". Archived from the original on 30 June 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ "aluminium – Definition of aluminium (Webster's New World and American Heritage Dictionary)". Archived from the original on 16 September 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ "alumium", Oxford English Dictionary. Ed. J.A. Simpson and E.S.C. Weiner, second edition Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989. OED Online Oxford University Press. Accessed 29 October 2006. Citation is listed as "1808 SIR H. DAVY in Phil. Trans. XCVIII. 353". The ellipsis in the quotation is as it appears in the OED citation.

- ↑ Davy, Humphry (1808). "Electro Chemical Researches, on the Decomposition of the Earths; with Observations on the Metals obtained from the alkaline Earths, and on the Amalgam procured from Ammonia". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. Royal Society of London. 98: 353. doi:10.1098/rstl.1808.0023

. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

. Retrieved 10 December 2009. - ↑ Davy, Humphry (1812). Elements of Chemical Philosophy. ISBN 0-217-88947-6. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

- ↑ Cutmore, Jonathan. "Quarterly Review Archive". Romantic Circles. University of Maryland. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ Young, Thomas (September 1812). "Elements of Chemical Philosophy By Sir Humphry Davy". Quarterly Review. John Murray. VIII (15): 72. ISBN 0-217-88947-6. 210. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

- 1 2 Exley, C. (2013). "Human exposure to aluminium". Environmental Science: Processes & Impacts. 15 (10): 1807. doi:10.1039/C3EM00374D.

- ↑ Banks, W.A.; Kastin, A. J. (1989). "Aluminum-induced neurotoxicity: alterations in membrane function at the blood–brain barrier". Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 13 (1): 47–53. PMID 2671833. doi:10.1016/S0149-7634(89)80051-X.

- 1 2 Dolara, Piero (21 July 2014). "Occurrence, exposure, effects, recommended intake and possible dietary use of selected trace compounds (aluminium, bismuth, cobalt, gold, lithium, nickel, silver)". International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition. Informa Plc. 65: 911–924. ISSN 1465-3478. PMID 25045935. doi:10.3109/09637486.2014.937801.

- ↑ Slanina, P.; French, W.; Ekström, L. G.; Lööf, L.; Slorach, S.; Cedergren, A. (1986). "Dietary citric acid enhances absorption of aluminum in antacids". Clinical Chemistry. American Association for Clinical Chemistry. 32 (3): 539–541. PMID 3948402.

- ↑ Van Ginkel, M. F.; Van Der Voet, G. B.; D'haese, P. C.; De Broe, M. E.; De Wolff, F. A. (1993). "Effect of citric acid and maltol on the accumulation of aluminum in rat brain and bone". The Journal of laboratory and clinical medicine. 121 (3): 453–60. PMID 8445293.

- ↑ Darbre, P. D. (2006). "Metalloestrogens: an emerging class of inorganic xenoestrogens with potential to add to the oestrogenic burden of the human breast". Journal of Applied Toxicology. 26 (3): 191–7. PMID 16489580. doi:10.1002/jat.1135.

- 1 2 Ferreira, P. C.; Piai Kde, A.; Takayanagui, A. M.; Segura-Muñoz, S. I. (2008). "Aluminum as a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease". Revista Latino-americana de enfermagem. 16 (1): 151–7. PMID 18392545. doi:10.1590/S0104-11692008000100023

.

. - ↑ Gitelman, H. J. "Physiology of Aluminum in Man" Archived 19 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine., in Aluminum and Health, CRC Press, 1988, ISBN 0-8247-8026-4, p. 90

- ↑ Yokel RA; Hicks CL; Florence RL (2008). "Aluminum bioavailability from basic sodium aluminum phosphate, an approved food additive emulsifying agent, incorporated in cheese". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 46 (6): 2261–6. PMC 2449821

. PMID 18436363. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2008.03.004.

. PMID 18436363. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2008.03.004. - ↑ Aluminum Toxicity Archived 3 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine. from NYU Langone Medical Center. Last reviewed November 2012 by Igor Puzanov, MD

- ↑ "CDC – NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards – Aluminum". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ "CDC – NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards – Aluminum (pyro powders and welding fumes, as Al)". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ Ferreira PC; Piai Kde A; Takayanagui AM; Segura-Muñoz SI (2008). "Aluminum as a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease". Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 16 (1): 151–7. PMID 18392545. doi:10.1590/S0104-11692008000100023

. Archived from the original on 26 May 2009.

. Archived from the original on 26 May 2009. - ↑ Aluminium and Alzheimer's disease Archived 11 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine., The Alzheimer's Society. Retrieved 30 January 2009.

- ↑ Rondeau, V.; Jacqmin-Gadda, H.; Commenges, D.; Helmer, C.; Dartigues, J.-F. (2008). "Aluminum and Silica in Drinking Water and the Risk of Alzheimer's Disease or Cognitive Decline: Findings From 15-Year Follow-up of the PAQUID Cohort". American Journal of Epidemiology. 169 (4): 489–96. PMC 2809081

. PMID 19064650. doi:10.1093/aje/kwn348.