Carroll A. Deering

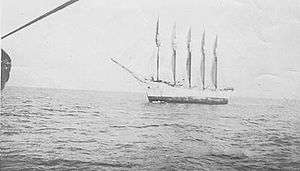

Schooner Carroll A. Deering, as seen from the Cape Lookout lightship on January 28, 1921. (US Coast Guard) | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Carroll A. Deering |

| Namesake: | G.G. Deering's son |

| Builder: | G.G. Deering Company, Bath, Maine |

| Completed: | 1919 |

| Fate: | Found wrecked January 31, 1921 |

| General characteristics | |

Carroll A. Deering was a five-masted commercial schooner that was found run aground off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, in 1921. Its crew went missing. The Deering is one of the most written-about maritime mysteries in history, with claims that it was a victim of the Bermuda Triangle, although the evidence points towards a mutiny or possibly piracy.

Overview

The Carroll A. Deering was built in Bath, Maine, in 1919 by the G.G. Deering Company for commercial use. The owner of the company named the ship after his son. The vessel was designed to carry cargo and had been in service for a year when it began its final voyage to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

The Deering’s last voyage

On August 19, 1920, the Deering prepared to sail from Norfolk, Virginia, to Rio de Janeiro with a cargo of coal. The ship was captained by William H. Merritt. Merritt's son, Sewall, was his first mate. He had a ten-man crew made up entirely of Scandinavians (mostly Danes). On August 22, 1920, the Deering left Newport News. In late August, Captain Merritt fell ill and had to be let off at the port of Lewes, Delaware, along with his son. The Deering Company hastily recruited Captain W. B. Wormell, a retired 66-year-old veteran captain, to replace him. Charles B. McLellan was hired on as first mate.

The vessel set sail for Rio on September 8, 1920, and arrived there, delivering its cargo without incident. Wormell gave his crew leave and met with a Captain Goodwin, an old friend who captained another cargo vessel. Wormell spoke of his crew with disdain, though he claimed to trust the engineer, Herbert Bates.[1] The Deering left Rio on December 2, 1920, and stopped for supplies in Barbados. First Mate McLellan got drunk in town and complained to Captain Hugh Norton of the Snow that he could not discipline the crew without Wormell interfering, and that he had to do all the navigation owing to Wormell's poor eyesight.[2] Later Captain Norton, his first mate and another captain were in the Continental Café and heard McLellan say, "I'll get the captain before we get to Norfolk, I will."[2] McLellan was arrested, but on January 9 Wormell forgave him, bailed him out of jail, and set sail for Hampton Roads.[3]

The ship was next sighted by the Cape Lookout lightship in North Carolina on January 28, 1921, when the vessel hailed it. The lightship's keeper, Captain Jacobson, reported that a thin man with reddish hair and a foreign accent told him the vessel had lost its anchors in a storm off Cape Fear. Jacobson took note of this, but his radio was out, so he was unable to report it. He noticed that the crew seemed to be "milling around" on the fore deck of the ship, an area where they were usually not allowed.

The wreck

On January 31, 1921, the Deering was sighted run aground on Diamond Shoals, an area off the coast of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, that has long been notorious as a common site of shipwrecks. Rescue ships were unable to approach the vessel owing to bad weather. The ship was not boarded until February 4, and it became clear that the ship had been completely abandoned. The ship's log and navigation equipment were gone, and the crew's personal effects and the ship's two lifeboats were gone as well. In the vessel's galley it appeared that certain foodstuffs were being prepared for the next day's meal at the time of the abandonment. The Coast Guard vessel Manning attempted to salvage the Deering, but found this impossible. The vessel was scuttled, using dynamite, on March 4 to prevent her from becoming a danger to other vessels and a portion of its bow drifted ashore on Ocracoke island.

Investigation

The U.S. government launched an extensive investigation into the disappearance of the crew of the Deering. Five departments of the government—Commerce, Treasury, Justice, Navy, and State—looked into the case. Herbert Hoover, then Secretary of Commerce, was intrigued by the fact that several other vessels of various nationalities—most notably the sulfur freighter Hewitt—had also disappeared in roughly the same area. Though most of these vessels were later revealed to have been sailing in the vicinity of a series of particularly vicious hurricanes, the Hewitt and Deering were proven to have been sailing away from the area of the storm at the time. Hoover's assistant, Lawrence Ritchey, was placed in charge of the investigation. Ritchey tried to chart what happened to the vessel between its last sighting at Cape Lookout and its running aground at Diamond Shoals by reading the log books of the Coast Guard lightships stationed at those places.

The investigation remained largely fruitless. When an Italian inquiry into the disappearance of the vessel Monte San Michele confirmed that there had been heavy hurricanes in the vicinity, most of the conspiracy theories were dropped and mutiny was generally accepted as the explanation for the Deering incident.

The investigation was closed in late 1922 without an official finding on the incident.

Speculation

There were a number of popular theories about the incident. It seemed at first that an external force was responsible for the disappearance of the crew.

On April 11, 1921, a man named Christopher Columbus Gray claimed to have found a message in a bottle floating in the waters of Buxton Beach, North Carolina; he swiftly turned it over to the authorities. The text of the message was as follows:

DEERING CAPTURED BY OIL BURNING BOAT SOMETHING LIKE CHASER. TAKING OFF EVERYTHING HANDCUFFING CREW. CREW HIDING ALL OVER SHIP NO CHANCE TO MAKE ESCAPE. FINDER PLEASE NOTIFY HEADQUARTERS DEERING.

The handwriting in the letter was identified as that of the ship's engineer, Bates, by the widow of Captain Wormell, and the bottle was proven to have been manufactured in Brazil. This, along with a sighting of a "mysterious" steamer that arrived at the Cape Lookout lightship in the wake of the Deering, suggested hostile action. The message also raised skepticism: if a crew member did manage to get hold of paper, pen, and bottle and write a letter, why would he request that the company be notified, as opposed to the police or Coast Guard? According to Kusche, Christopher Columbus Gray later admitted the letter had been forged.

The following theories were considered by the U.S. government in its investigation:

- Hurricanes: The U.S. government, particularly the Weather Bureau, strongly advocated a series of vicious hurricanes raging in the Atlantic as the cause of the disappearances. As mentioned above, however, both the Deering and the Hewitt were heading away from the path of these storms. In any case, several authors, including Larry Kusche and Richard Winer, have pointed out that the state of the ship indicates an orderly rather than panicked evacuation.

- Piracy: Captain O.W. Parker of the United States Marine Shipping Board certainly believed piracy responsible; he stated that, in his opinion, "Piracy without a doubt still exists as it has since the days of the Phoenicians". Captain Wormell's widow was a particularly strong advocate of this theory. It was believed that a group of pirates were responsible for the various disappearances; however, no real evidence of this theory emerged, and no suspected pirates were ever caught.

- Russian/Communist Piracy: During a police raid on the headquarters of the United Russian Workers Party (a Communist front group) in New York City, officers found papers that called on members of the organization to seize American ships and sail them to Russia. These papers showed that a Communist plot was afoot, and was circumstantially linked to several shipboard strikes the previous year. This was widely believed in regard to the Deering at the time, particularly by hardline anti-communists in the government. Though an intriguing suggestion, no definitive proof that any of these activities were actually carried out has surfaced.

- Rum Runners: A similar theory to the above speculates that a group of liquor smugglers working out of the Bahamas stole the ship to use as a rum-running vessel (this was during the Prohibition era). The Deering was large enough, according to Richard Winer's Ghost Ships, to carry roughly a million dollars' worth of liquor in its hold. On the other hand, it is doubtful that such a conspicuous, easily identifiable and comparatively slow vessel would constitute a choice target for smugglers.

- Mutiny: Wormell's known conflict with his first mate and derisive comments towards his crew while in Rio de Janeiro suggested that something may have been amiss between the captain and his men on the voyage. Captain Jacobson at Cape Lookout certainly thought it odd; the man who hailed his vessel was definitely not Captain Wormell, and he was not an officer by all accounts. Senator Frederick Hale of Maine advocated this theory, stating it was "a plain case of mutiny". Discontent with the captain could certainly have caused a mutiny of the crew, but once again, nothing definitive has ever been proven.

Perhaps inevitably, a more outlandish type of explanation became popular within a few decades of the incident:

- Paranormal Explanation: The disappearance of the ship's crew has been cited by innumerable authors dealing with anomalous phenomena and the supernatural. Charles Fort, in his book Lo! (1931), first mentioned this vessel in a "mysterious" context, and many subsequent chroniclers of sea mysteries have followed suit. Since this vessel sailed in the area generally considered to be part of the so-called Bermuda Triangle, the disappearance of the crew has often been tied to this fact.[4] However it should be noted that the ship's resting place (Diamond Shoals) and its last known point of sighting and communication (Cape Lookout) are several hundred miles away from the area generally known as the Bermuda Triangle.

Conclusion

No official explanation for the disappearance of the crew of the Carroll A. Deering was ever offered, though all of the concrete evidence suggests mutiny. The case is a favorite of paranormal and Bermuda Triangle hobbyists and has gained a reputation as one of the truly great maritime mysteries. It is also possible that the Deering's crew simply abandoned ship after the vessel grounded on Diamond Shoals and, unable to row to shore, were swept out to sea and a certain death in their small open lifeboats.

References

- ↑ Graveyard of the Atlantic page

- 1 2 Simpson, Bland (2005), Ghost Ship of Diamond Shoals: The Mystery of the Carroll A. Deering, UNC Press, pp. 55–7, ISBN 978-0-8078-5617-8

- ↑ Bland (2005) p60

- ↑ Eyers, Jonathan (2011). Don't Shoot the Albatross!: Nautical Myths and Superstitions. A&C Black, London, UK. ISBN 978-1-4081-3131-2.

Further reading

- Newspapers

- "Piracy Suspected In Disappearance Of 3 American Ships," New York Times, June 21, 1921.

- "Bath Owners Skeptical," New York Times, June 22, 1921.

- "Deering Skipper's Wife Caused Investigation," New York Times, June 22, 1921.

- "More Ships Added To Mystery List," New York Times, June 22, 1921.

- "Hunt On For Pirates," Washington Post, June 21, 1921

- "Comb Seas For Ships," Washington Post, June 22, 1921.

- "Port Of Missing Ships Claims 3000 Yearly," Washington Post, July 10, 1921.

- Books

- Ghost Ship of Diamond Shoals, The Mystery of the Carroll A. Deering (2002), Bland Simpson

- Lo! (1931), Charles Fort - ISBN 1-870870-89-1

- Invisible Horizons (1965), Vincent Gaddis

- The Bermuda Triangle (1974), Charles Berlitz

- The Bermuda Triangle Mystery: Solved (1975), Larry Kusche - ISBN 0-87975-971-2

- Ghost Ships (2000), Richard Winer

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carroll A. Deering. |

- C.A. Deering, Graveyard of the Atlantic.

Coordinates: 35°15′45″N 75°29′30″W / 35.262440°N 75.491695°W