Carnivora

| Carnivorans Temporal range: 42–0 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Various carnivorans, with feliforms (tiger, spotted hyena and African civet) to the left, and caniforms (brown bear, gray wolf and wolverine) to the right | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| (unranked): | Carnivoramorpha |

| Order: | Carnivora Bowdich (1821)[2] |

| Families | |

| |

Carnivora (/kɑːrˈnɪvərə/;[3][4] from Latin carō (stem carn-) "flesh" and vorāre "to devour") is a diverse scrotiferan order that includes over 280 species of placental mammals. Its members are formally referred to as carnivorans, whereas the word "carnivore" (often popularly applied to members of this group) can refer to any meat-eating organism. Carnivorans are the most diverse in size of any mammalian order, ranging from the least weasel (Mustela nivalis), at as little as 25 g (0.88 oz) and 11 cm (4.3 in), to the polar bear (Ursus maritimus), which can weigh up to 1,000 kg (2,200 lb), to the southern elephant seal (Mirounga leonina), whose adult males weigh up to 5,000 kg (11,000 lb) and measure up to 6.9 m (23 ft) in length.

Some carnivorans, such as cats and pinnipeds, depend entirely on meat for their nutrition. Others, such as raccoons and bears, depending on the local habitat, are more omnivorous: the giant panda is almost exclusively a herbivore, but will take fish, eggs and insects, while the polar bear subsists mainly on seals. Carnivorans have teeth and claws adapted for catching and eating other animals. Many hunt in packs and are social animals, giving them an advantage over larger prey.

Carnivorans are split into two suborders: feliforms ("cat-like") and caniforms ("dog-like").

Taxonomy

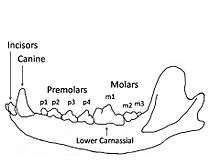

Carnivorans all share the same arrangement of teeth in which the last upper premolar (named P4) and the first lower molar (named m1) have blade-like enamel crowns that work together as carnassial teeth to shear meat. Carnivorans have had this arrangement for over 60 million years with many adaptions, and these dental adaptions help identify carnivoran species and groupings of species.[5]

Evolution

Carnivorans evolved in North America out of members of the family Miacidae (miacids) about 42 million years ago.[1] They soon split into cat-like and dog-like forms (Feliformia and Caniformia). Their molecular phylogeny[6] shows the extant Carnivora are a monophyletic group, the crown group of the Carnivoramorpha.

Distinguishing features

Most carnivorans are terrestrial; they usually have strong, sharp claws, typically with five, but never fewer than four, toes on each foot, and well-developed, prominent canine teeth, cheek teeth (premolars, and molars) that generally have cutting edges. The last premolar of the upper jaw and first molar of the lower are termed the carnassials or sectorial teeth. These blade-like teeth occlude (close) with a scissor-like action for shearing and shredding meat. Carnassials are most highly developed in the Felidae and the least developed in the Ursidae. Carnivorans have six incisors and two conical canines in each jaw. The only two exceptions to this are the sea otter (Enhydra lutris), which has four incisors in the lower jaw, and the sloth bear (Melursus ursinus), which has four incisors in the upper jaw. The number of molars and premolars is variable between carnivoran species, but all teeth are deeply rooted and are diphyodont.[7] Incisors are retained by carnivorans and the third incisor is commonly large and sharp (canine-like). Carnivorans have either four or five digits on each foot, with the first digit on the forepaws, also known as the dew claw, being vestigial in most species and absent in some.

The superfamily Canoidea (or suborder Caniformia) – Canidae (wolves, dogs and foxes), Mephitidae (skunks and stink badgers), Mustelidae (weasels, badgers, and otters), Procyonidae (raccoons), Ursidae (bears), Ailuridae (red panda), Otariidae (eared seals), Odobenidae (walrus), and Phocidae (earless seals) (the last three families formerly classified in the superfamily Pinnipedia) and the extinct family Amphicyonidae (bear-dogs) – are characterized by having nonchambered or partially chambered auditory bullae, nonretractable claws, and a well-developed baculum. Most species are rather plain in coloration, lacking the flashy spotted or rosetted coats like many species of felids and viverrids have. This is because Canoidea tend to range in the temperate and subarctic biomes, although Mustelidae and Procyonidae have a few tropical species. Most are terrestrial, although a few species, like procyonids, are arboreal. All families except the Canidae and a few species of Mustelidae are plantigrade. Diet is varied and most tend to be omnivorous to some degree, and thus the carnassial teeth are less specialized. Canoidea have more premolars and molars in an elongated skull.

The superfamily Feloidea (or suborder Feliformia)– Felidae (cats), Prionodontidae (Asiatic linsangs), Herpestidae (mongooses), Hyaenidae (hyenas), Viverridae (civets), and Eupleridae (Malagasy carnivorans), as well as the extinct family Nimravidae (paleofelids) – often have spotted, rosetted or striped coats, and tend to be more brilliantly colored than their Canoidean counterparts. This is because these species tend to range in tropical habitats, although a few species do inhabit temperate and subarctic habitats. Many are arboreal or semiarboreal, and the majority are digitigrade. Diet tends to be more strictly carnivorous, especially in the family Felidae. They have fewer teeth and shorter skulls, with much more specialized carnassials meant for shearing meat. Feliformia claws are often retractile, or rarely, semiretractile. The terminal phalanx, with the claw attached, folds back in the forefoot into a sheath by the outer side of the middle phalanx of the digit, and is retained in this position when at rest by a strong elastic ligament. In the hindfoot, the terminal joint or phalanx is retracted on to the top, and not the side of the middle phalanx. Deep flexor muscles straighten the terminal phalanges, so the claws protrude from their sheaths, and the soft "velvety" paw becomes suddenly converted into a formidable weapon. The habitual retraction of the claws preserves their points from wear.

The superfamily Pinnipedia (walruses, seals, and sea lions), now considered to be part of Caniformia, are medium to large (to 6.5 m) aquatic mammals. Being homeothermic (warm-blooded) marine mammals, pinnipeds need a low surface area to body mass ratio. Otherwise, they would suffer from excessive heat loss due to water's high capacity for heat conduction. The body is usually insulated with a thick layer of fat called blubber and typically covered with hair. The digits are not separate, but connected by a thick web that forms flippers for swimming; thus, the forelimbs and hindlimbs are transformed into paddles. This enables them to dive at extreme depths (600 m for the Weddell seal). They can remain underwater for long periods of time, sometimes an hour or more, but most dives are usually short. The facial region of skull is relatively small, with pinnae very small or lacking, and the vibrissae are well developed. The molariform teeth are mostly homodont and the canines are well developed. The tail is very short or absent, the ears are small or absent as well, and the external genitalia are hidden in slits or depressions in the body.

Skull structure

Members of Carnivora have a characteristic skull shape with relatively large brains encased in a heavy skull. The skull has a highly developed zygomatic arch just behind the maxilla (common to all mammals and their cynodont forebears), and they have ossified external auditory bullae. Feloidea have a two-chambered auditory bulla. In addition to allowing extra room for the passage of muscles to work the lower jaw, the zygomatic arch also allows for differentiation of separate muscle groups to be involved in biting and chewing. Masseters attach from the dentary (specifically, the masseteric fossa) to the zygomatic arch and onto the maxilla in front of the arch, providing crushing force. The temporalis attaches from the dentary (specifically, the coronoid process) to the side of the braincase, providing torque about the axis of jaw articulation.

In comparing the skulls of carnivores and herbivores, it can be seen that the shearing force of the temporalis is somewhat more important to carnivores, which have more room on the braincase (this is not unrelated to carnivoran intelligence) and commonly develop a sagittal crest (running from posterior to anterior on the skull), providing yet additional room for temporalis attachment. Carnivoran jaws can only move on a vertical axis, in an up-and-down motion, and cannot move from side-to-side. The jaw joint in carnivores tends to lie within the plane of tooth occlusion, an arrangement that further emphasizes shearing (as in a pair of scissors). In herbivores, the crushing force of the masseters is relatively more important than is shearing. The jaw joint is generally well above the plane of tooth occlusion, allowing extra room for masseteric attachment on the dentary and causing the rotation of the lower jaw to be translated into straight-ahead crushing force between the teeth of the upper and lower jaws.

Dentition

Dentition relates to the arrangement of teeth in the mouth, with the dental notation for the upper-jaw teeth using the upper-case letters I to denote incisors, C for canines, P for premolars, and M for molars, and the lower-case letters i, c, p and m to denote the mandible teeth. Teeth are numbered using one side of the mouth and from the front of the mouth to the back. In carnivores, the upper premolar P4 and the lower molar m1 form the carnassials that are used together in a scissor-like action to shear the muscle and tendon of prey.[8]

Physiology

Carnivora have a simple stomach adapted to digest primarily meat, as compared to the elaborate digestive systems of herbivorous animals, which are necessary to break down tough, complex plant fibers. The caecum is either absent or short and simple, and the colon is not sacculated or much wider than the small intestine. Most species of Carnivora are, to some degree, omnivorous, except the Felidae and Pinnipedia, which are obligate carnivores. Most have highly developed senses, especially vision and hearing, and often a highly acute sense of smell in many species, such as in the Canoidea. They are excellent runners: some are long-distance runners, but more commonly are sprinters. Even bears and raccoons, although seemingly slow and clumsy, are capable of remarkable bursts of speed.

Diet specializations

Carnivorans include carnivores, omnivores, and even a few primarily herbivorous species, such as the giant panda and the binturong. Important teeth for carnivorans are the large, slightly recurved canines, used to dispatch prey, and the carnassial complex, used to rend meat from bone and slice it into digestible pieces. Dogs have molar teeth behind the carnassials for crushing bones, but cats have only a greatly reduced, functionless molar behind the carnassial in the upper jaw. Cats will strip bones clean but will not crush them to get the marrow inside. Omnivores, such as bears and raccoons, have developed blunt, molar-like carnassials. Carnassials are a key adaptation for terrestrial vertebrate predation; all other placental orders are primarily herbivores, insectivores, or aquatic.

Reproductive system

Most male carnivorans have a baculum, although it is relatively short in felids, and absent in hyenas.[9] Carnivorans tend to produce a single litter annually, but some produce multiple litters a year, and larger carnivorans, like bears, have gaps of 2–3 yr between litters. The average gestation period lies between 50 and 115 days, although the ursids and mustelids have delayed implantation, thus extending the gestation period six to 9 months beyond the normal period. Litter sizes are usually small, ranging from one to 13 young, which are born with underdeveloped eyes and ears. In most species, the mother has exclusive or at least primary care of the offspring. Many species of carnivorans are solitary, but a few are gregarious.

Phylogeny

Carnivorans evolved from members of the family Miacidae (miacids, now recognized as paraphyletic[10]). The transition from Miacidae to Carnivora was a general trend in the middle and late Eocene, with taxa from both North America and Eurasia involved. The divergence of carnivorans from other miacids, as well as the divergence of the two clades within Carnivora, Caniformia and Feliformia, is now inferred to have happened in the middle Eocene, about 42 million years ago (mya).[1]

Traditionally, the extinct family Viverravidae (viverravids) had been thought to be the earliest carnivorans, with fossil records first appearing in the Paleocene of North America about 60 mya, but recently described evidence from cranial morphology now places them outside the order Carnivora.[11]

The Miacidae are not a monophyletic group, but a paraphyletic array of stem taxa. Today, Carnivora is restricted to the crown group, Carnivora and miacoids are grouped in the clade Carnivoramorpha, and the miacoids are regarded as basal carnivoramorphs. Based on dental features and braincase sizes, it is now known that Carnivora must have evolved from a form even more primitive than Creodonta, and thus these two orders may not even be sister groups.[12] The Carnivora, Creodonta, Pholidota, and a few other extinct orders are informally grouped together in the clade Ferae. Older classification schemes divided the order into two suborders: Fissipedia (which included the families of primarily land Carnivora) and Pinnipedia (which included the true seals, eared seals, and walrus). However, it is now recognized that the Fissipedia is a paraphyletic group and that the pinnipeds were not the sister group to the fissipeds but rather had arisen from among them.

Carnivora are generally divided into the suborders Feliformia (cat-like) and Caniformia (dog-like), the latter of which includes the pinnipeds. The pinnipeds are part of a clade, known as the Arctoidea, which also includes the Ursidae (bears) and the superfamily Musteloidea. The Musteloidea in turn consists of the Mustelidae (mustelids: weasels), Procyonidae (procyonids: raccoons), Mephitidae (skunks) and Ailurus (red panda). The oldest caniforms are the Miacis species Miacis cognitus, the Amphicyonidae (bear-dogs) such as Daphoenus, and Hesperocyon (of the family Canidae, subfamily Hesperocyoninae). Hesperocyonine canids first appeared in North America, and the earliest species is currently dated at 39.74 mya, but they were not represented in Europe until well into the Miocene, and not into Asia and Africa until the Pliocene. Miacis and Amphicyonidae were the first of the caniforms to split from the others and are sometimes considered to be sister groups to Ursidae, but the exact closeness of Amphicyonidae and Ursidae, as well as Arctoidae to Ursidae, is still uncertain. The Canidae (wolves, coyotes, jackals, foxes and dogs) are generally considered to be the sister group to Arctoidea.[12][13][14] The Ursidae first occur in North America in the Late Eocene (ca. 38 mya) as the very small and graceful Parictis that had a skull only 7 cm long. Like the canids, this family does not appear in Eurasia and Africa until the Miocene. The other caniform families Amphicyonidae, Mustelidae and Procyonidae occur in both the Old World and the New World by the Late Eocene and Early Oligocene.[12]

The ancestor of all Feliformia evolved from the Caniformia-Feliformia split. Nandinia, the African palm civet, seems to be the most primitive of all the feliforms and the very first to split from the others.[6] The Asiatic linsangs of the genus Prionodon (traditionally placed in the Viverridae) form a family of their own, as some recent[15] studies indicate that Prionodon is actually the closest living relative to the cats. The Nimravidae are sometimes seen as the most basal of all feliforms and the first to split from the others, but there is a possibility that Nimravidae might not even belong within the order,[14] and therefore its position as a clade within Carnivora is currently unstable. Other studies indicate that the barbourofelids form a separate family, which is closely related to the true felids instead of being related to the nimravids. Recognizable nimravid fossils date from the late Eocene (37 mya), from the Chadronian White River Carnivora Formation at Flagstaff Rim, Wyoming. Nimravid diversity appears to have peaked about 28 mya. The hypercarnivorous (strictly meat-eating) nimravid feliforms were extinct in North America after 26 mya and felids did not arrive in North America until the early middle Miocene (16 mya).

It has been suggested that canids evolved hypercarnivorous morphologies because feliforms were absent during this period (the "cat-gap", 26-18.5 mya), however recent data do not support this hypothesis. Hypercarnivore feliforms (felids and nimravids) occupied an area that canids did not and where felids, nimravids, and hypercarnivorous creodonts are found. Hypercarnivorous canids were present before the disappearance of the nimravids, and all became extinct before the appearance of felids. Following the extinction of nimravids, only three taxa originated, two of which were relatively small in body size. Disparity increased during the "cat-gap" even with the extinction of the hypercarnivorous extremes. This was due to the extinction of morphological intermediates, and because carnivorans began to occupy hypocarnivorous (nonmeat-specialist) morphospace for the first time in North America. Procyonids did not arrive in North America until the early Miocene, and "modern" ursids (e.g., Ursinae), did not arrive until the late Miocene. Extinct lineages of Ursidae were present in North America from the late Eocene through the Miocene and amphicyonids (bear-dogs) were present during this period as well, but occupied a morphospace generally shared with canids and not in close proximity to ursids. A large question remains as to why there was a progressive decline in hypercarnivorous carnivoramorphans during the late Oligocene/early Miocene. During this period all hypercarnivorous forms disappeared from the fossil record, including hypercarnivorous feliforms, canids, and mustelids. One possible explanation is climate change. Earth was gradually cooling after the late Paleocene, and over a period spanning the Eocene/Oligocene boundary, a dramatic climatic cooling event occurred.[16]

A recent study has finally resolved the exact position of Ailurus: the red panda is neither a procyonid nor an ursid, but forms a monotypic family, with the other musteloids as its closest living relatives. The same study also showed that the mustelids are not a primitive family, as was once thought. Their small body size is a secondary trait—the primitive body form of the arctoids was large, not small.[13] Recent molecular studies also suggest that the endemic Carnivora of Madagascar, including three genera usually classed with the civets and four genera of mongooses classed with the Herpestidae, are all descended from a single ancestor. They form a single sister taxon to the Herpestidae. The hyenas are also closely related to this clade.

Classification

When order Carnivora was first discovered and named, there were only 5 families

- Family Canidae: Dogs and foxes

- Family Felidae: Cats

- Family Mustelidae: Weasels, badgers, raccoons, otters, skunks, and relatives (combining today's families Mustelidae and Mephitidae)

- Family Ursidae: Bears, and pandas (combining today's families Ailuridae, Procyonidae, and Ursidae)

- Family Viverridae: Mongooses, civets, hyenas, and relatives (combining today's families Eupleridae, Herpestidae, Hyaenidae, Nandiniidae, Prionodontidae, and Viverridae)

The most common modern classification scheme divides the Carnivora into sixteen living and a number of extinct families, as follows:[17]

- ORDER CARNIVORA

- Suborder Feliformia ("cat-like")

- Superfamily †Stenoplesictoidea

- Family †Stenoplesictidae

- Family †Percrocutidae

- Family †Nimravidae: false sabre-tooth cats (5–36 mya)

- Family Nandiniidae: African palm civet; one species

- Superfamily Feloidea

- Family Prionodontidae: Asiatic linsangs; two species in one genus

- Family †Barbourofelidae (6–18 mya)

- Family Felidae: cats; 41 species in 15 genera

- Superfamily Viverroidea

- Family Viverridae: civets and allies; 34 species in 15 genera[18]

- Superfamily Herpestoidea

- Family Hyaenidae: hyenas and aardwolf; four species in three genera

- Family Eupleridae: Malagasy carnivorans; 10 species in seven genera

- Family Herpestidae: mongooses and allies; 33 species in 14 genera

- Superfamily †Stenoplesictoidea

- Suborder Caniformia ("dog-like")

- Family †Amphicyonidae: bear-dogs (9–37 mya)

- Family Canidae: dogs and allies; 35 species in 12 genera

- Infraorder Arctoidea

- Superfamily Ursoidea

- Family †Hemicyonidae: (2–22 mya)

- Family Ursidae: bears; eight species in five genera

- Superfamily Pinnipedia

- Family †Enaliarctidae: (23–20 mya?)

- Family Odobenidae: walrus; one species

- Family Otariidae: eared seals; 15 species in seven genera

- Family Phocidae: true seals; 18 species in 13 genera

- Superfamily Musteloidea

- Family Ailuridae: red panda; one species

- Family Mephitidae: skunks and stink badgers; 12 species in four genera

- Family Mustelidae: weasels and allies; 57 species in 22 genera

- Family Procyonidae: raccoons and allies; 14 species in six genera

- Superfamily Ursoidea

- Suborder Feliformia ("cat-like")

Phylogenetic tree

The cladogram is based on Flynn (2005).[19]

| Carnivora |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Heinrich, R.E.; Strait, S.G.; Houde, P. (2008). "Earliest Eocene Miacidae (Mammalia: Carnivora) from northwestern Wyoming". Journal of Paleontology. 82 (1): 154–162. doi:10.1666/05-118.1.

- ↑ Bowditch, T. E. 1821. An analysis of the natural classifications of Mammalia for the use of students and travelers J. Smith Paris. 115. (refer pages 24, 33)

- ↑ "Carnivora". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House.

- ↑ "Carnivora". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- ↑ Wang, Xiaoming; Tedford, Richard H.; Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008. ISBN 0231135289, p1

- 1 2 Eizirik, E.; Murphy, W.J.; Koepfli, K.P.; Johnson, W.E.; Dragoo, J.W.; O'Brien, S.J. (2010). "Pattern and timing of the diversification of the mammalian order Carnivora inferred from multiple nuclear gene sequences". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 56: 49–63. PMID 20138220. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.01.033.

- ↑ http://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Carnivora/

- ↑ Wang, Xiaoming; Tedford, Richard H. (2008). Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History. Columbia University Press, New York. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-231-13529-0.

- ↑ Dixson, A. F. "Baculum length and copulatory behaviour in carnivores and pinnipeds (Grand Order Ferae)." Journal of Zoology 235.1 (1995): 67-76.

- ↑ Wesley-Hunt, G.D.; Flynn J.J. (2005). Phylogeny of the Carnivora: Basal Relationships Among the Carnivoramorphans, and Assessment of the Position of 'Miacoidea' Relative to Carnivora. Journal of Systematic Paleontology, 3: 1-28. doi:10.1017/S1477201904001518

- ↑ Polly, David, Gina D. Wesley-Hunt, Ronald E. Heinrich, Graham Davis and Peter Houde (2006). "Earliest Known Carnivoran Auditory Bulla and Support for a Recent Origin of Crown-Clade Carnivora (Eutheria, Mammalia)" (PDF). Palaeontology. 49 (5): 1019–1027. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2006.00586.x. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-11-18.

- 1 2 3 Kemp, T.S. (2005). The Origin and Evolution of Mammals. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850760-4.

- 1 2 Wesley-Hunt, Gina D.; John J. Flynn (2005). "Phylogeny of the Carnivores". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 3: 1–28. doi:10.1017/S1477201904001518. Archived from the original on 2010-11-18.

- 1 2 Wesley-Hunt, Gina D.; Lars Werdelin (2005). "Basicranial morphology and phylogenetic position of the upper Eocene carnivoramorphan Quercygale" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 50 (4): 837–846. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2007.

- ↑ Johnson, W.E.; Eizirik, E.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; Murphy, W.J.; Antunes, A.; Teeling, E.; O'Brien, S.J. (2006). "The Late Miocene Radiation of Modern Felidae: A Genetic Assessment". Science. 311: 73–77. PMID 16400146. doi:10.1126/science.1122277.

- ↑ Wesley-Hunt, Gina D. (2005). "The Morphological Diversification of Carnivores in North America". Paleobiology. 31: 35–55. ISSN 0094-8373. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2005)031<0035:TMDOCI>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Wilson, D.E.; Mittermeier, R.A., eds. (2009). Handbook of the Mammals of the World, Volume 1: Carnivora. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. pp. 50–658. ISBN 978-84-96553-49-1.

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 548–559. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Flynn, J. J.; Finarelli, J. A.; Zehr, S.; Hsu, J.; Nedbal, M. A. (2005). "Molecular phylogeny of the Carnivora (Mammalia): Assessing the impact of increased sampling on resolving enigmatic relationships". Systematic Biology. 54 (2): 317–37. PMID 16012099. doi:10.1080/10635150590923326.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to: Carnivora |

| The Wikibook Dichotomous Key has a page on the topic of: Carnivora |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Carnivora. |