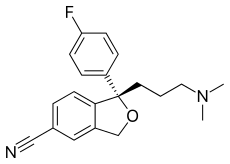

Skeletal formula

The skeletal formula, also called line-angle formula or shorthand formula, of an organic compound is a type of molecular structural formula that serves as a shorthand representation of a molecule's bonding and some details of its molecular geometry. A skeletal formula shows the skeletal structure or skeleton of a molecule, which is composed of the skeletal atoms that make up the molecule.[1] It is represented in two dimensions, as on a page of paper. It employs certain conventions to represent carbon and hydrogen atoms, which are the most common in organic chemistry.

An early form of this representation was first developed by the organic chemist Friedrich August Kekulé von Stradonitz. For this reason, they are sometimes termed Kekulé structures.[2] Skeletal formulae have become ubiquitous in organic chemistry, partly because they are relatively quick and simple to draw, and also because the curved arrow notation used for discussions of reaction mechanism and/or delocalization can be readily superimposed. As in Lewis structures, covalent bonds are indicated by line segments, with a doubled or tripled line segment indicating double or triple bonding, respectively. Likewise, skeletal formulae generally indicate formal charges associated with each atom (although lone pairs are usually optional, see below). In fact, skeletal formulae can be thought of as abbreviated Lewis structures that observe the following conventions: (1) Carbon atoms are generally represented by the vertices (intersections and termini) of line segments. As exceptions, methyl groups are often explicitly written out as Me or CH3, while cumulene carbons are usually represented by a heavy center dot. (2) Hydrogen atoms attached to carbon are implied: an unlabeled vertex is understood to be a carbon atom attached to the number of hydrogens required to satisfy the octet rule, while a vertex labeled with a formal charge and/or nonbonding electrons is understood to have the number of hydrogen atoms required for consistency with these properties. Frequently, acetylenic and formyl hydrogens are also explicitly shown for the sake of clarity. (3) Hydrogen atoms attached to a heteroatom must be explicitly shown; the heteroatom and hydrogen atoms attached thereto are usually shown as a single group (e.g., OH, NH2) without explicitly showing the hydrogen–heteroatom bond; (4) Nonbonding electron pairs on heteroatoms are optionally shown, while ones on carbon (e.g., carbenes) must be indicated explicitly.

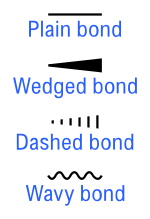

As additional conventions, wedged or dashed line segments are employed to indicate bonds pointing out of or receding into the plane of the paper, respectively, as a means of representing absolute and/or relative stereochemistry. Bonds to sp2 and/or sp3 hybridized carbon atoms are conventionally represented using 120° angles whenever possible. (If all four substituents to a tetrahedral carbon are explicitly shown, bonds to the two in-plane substituents meet at 120°, while the other two substituents, shown with wedged and dashed bonds, subtend a smaller angle of ~60°.) On the other hand, the linear geometry at sp hybridized atoms is normally depicted by line segments meeting at 180°. Carbo- and heterocycles (3 to 8 atoms) are generally represented as regular polygons, whereas larger ring sizes tend to be represented by concave polygons.

In the standard depiction of a molecule, the canonical form (resonance structure) with the greatest contribution is drawn. However, the skeletal formula is understood to represent the "real molecule" — that is, the weighed average of all contributing canonical forms. Thus, in cases where two or more canonical forms contribute with equal weight (e.g., in benzene, or a carboxylate anion) and one of the canonical forms is selected arbitrarily, the skeletal formula is understood to depict the true structure, containing equivalent bonds of fractional order, even though the delocalized bonds are depicted as nonequivalent single and double bonds.

Several other methods for depicting chemical structures are also commonly used in organic chemistry (though less frequently than skeletal formulae). For example, conformational structures look similar to skeletal formulae and are used to depict the approximate positions of the atoms in a molecule, as a perspective drawing. Other types of representations, e.g., Newman projections, Haworth projections and Fischer projections, also look somewhat similar to skeletal formulae. However, there are differences in the conventions used, and the reader needs to be aware of them in order to understand the structural details that are encoded in these depictions.

The skeleton

The skeletal structure of an organic compound is the series of atoms bonded together that form the essential structure of the compound. The skeleton can consist of chains, branches and/or rings of bonded atoms. Skeletal atoms other than carbon or hydrogen are called heteroatoms.[3]

The skeleton has hydrogen and/or various substituents bonded to its atoms. Hydrogen is the most common non-carbon atom that is bonded to carbon and, for simplicity, is not explicitly drawn. In addition, carbon atoms are not generally labelled as such directly (i.e. with a "C"), whereas heteroatoms are always explicitly noted as such (i.e. using "N" for nitrogen, "O" for oxygen, etc.)

Heteroatoms and other groups of atoms that give rise to relatively high rates of chemical reactivity, or introduce specific and interesting characteristics in the spectra of compounds are called functional groups, as they give the molecule a function. Heteroatoms and functional groups are known collectively as "substituents", as they are considered to be a substitute for the hydrogen atom that would be present in the parent hydrocarbon of the organic compound in question.

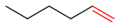

Implicit carbon and hydrogen atoms

For example, in the image below, the skeletal formula of hexane is shown. The carbon atom labeled C1 appears to have only one bond, so there must also be three hydrogens bonded to it, in order to make its total number of bonds four. The carbon atom labelled C3 has two bonds to other carbons and is therefore bonded to two hydrogen atoms as well. A ball-and-stick model of the actual molecular structure of hexane, as determined by X-ray crystallography, is shown for comparison, in which carbon atoms are depicted as black balls and hydrogen atoms as white ones.

NOTE: It doesn't matter which end of the chain you start numbering from, as long as you're consistent when drawing diagrams. The condensed formula or the IUPAC name will confirm the orientation. Some molecules will become familiar regardless of the orientation.

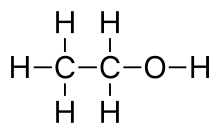

Any hydrogen atoms bonded to non-carbon atoms are drawn explicitly. In ethanol, C2H5OH, for instance, the hydrogen atom bonded to oxygen is denoted by the symbol H, whereas the hydrogen atoms which are bonded to carbon atoms are not shown directly. Lines representing heteroatom-hydrogen bonds are usually omitted for clarity and compactness, so a functional group like the hydroxyl group is most often written −OH instead of −O−H. These bonds are sometimes drawn out in full in order to accentuate their presence when they participate in reaction mechanisms.

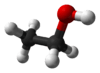

Shown below for comparison are a ball-and-stick model of the actual three-dimensional structure of the ethanol molecule in the gas phase (determined by microwave spectroscopy, left), the Lewis structure (centre) and the skeletal formula (right).

Explicit heteroatoms

All atoms that are not carbon or hydrogen are signified by their chemical symbol, for instance Cl for chlorine, O for oxygen, Na for sodium, and so forth. These atoms are commonly known as heteroatoms in the context of organic chemistry.

Pseudoelement symbols

There are also symbols that appear to be chemical element symbols, but represent certain very common substituents or indicate an unspecified member of a group of elements. These are known as pseudoelement symbols or organic elements.[4] The most widely used symbol is Ph, which represents the phenyl group. A list of pseudoelement symbols in common use is shown below:

General symbols

- X for any (pseudo)halogen atom

- L or Ln for a ligand or ligands

- M or Met for any metal atom ([M] is used to indicate a ligated metal, MLn, when the identities of the ligands are unknown or irrelevant)

- E for any electrophile (in some contexts, it is also used to indicate a p-block element)

- Nu for any nucleophile

- D for a deuterium (2H) atom

- T for a tritium (3H) atom

Alkyl groups

- R for any alkyl group or even any organyl group (Alk can be used to unambiguously indicate an alkyl group)

- Me for the methyl group

- Et for the ethyl group

- Pr, n-Pr, or nPr for the (normal) propyl group (Pr is also the symbol for the element praseodymium. However, since the propyl group is monovalent, while praseodymium is nearly always trivalent, ambiguity rarely, if ever, arises in practice.)

- i-Pr or iPr (i often italicized) for the isopropyl group

- Bu, n-Bu or nBu for the (normal) butyl group

- i-Bu or iBu (i often italicized) for the isobutyl group

- s-Bu or sBu for the secondary butyl group

- t-Bu or tBu for the tertiary butyl group

- Pn for the pentyl group (or Am for the synonymous amyl group, although Am is also the symbol for americium.)

- Cy or Chx for the cyclohexyl group

- Ad for the 1-adamantyl group

- Tr for the trityl group

Aromatic substituents

- Ar for any aromatic substituent (Ar is also the symbol for the element argon. However, argon is inert under all usual conditions encountered in organic chemistry, so the use of Ar to represent an aryl substituent never causes confusion.)

- Het for any heteroaromatic substituent

- Bn or Bzl for the benzyl group (not to be confused with Bz for benzoyl)

- Mes for the mesityl group

- Ph, Φ, or φ for the phenyl group (The use of phi for phenyl has been in decline)

- Tol for the tolyl group

- Cp for the cyclopentadienyl group (Cp was the symbol for cassiopium, a former name for lutetium)

- Cp* for the pentamethylcyclopentadienyl group

Functional groups

- Ac for the acetyl group (Ac is also the symbol for the element actinium. However, actinium is almost never encountered in organic chemistry, so the use of Ac to represent the acetyl group never causes confusion)

- Bz for the benzoyl group

- Piv for the pivalyl (t-butylcarbonyl) group

Leaving groups

See the article leaving group for further information

- Bs for the brosyl (p-bromobenzenesulfonyl) group

- Ms for the mesyl (methanesulfonyl) group

- Ns for the nosyl (p-nitrobenzenesulfonyl) group

- Tf for the trifyl (trifluoromethanesulfonyl) group

- Ts for tosyl (p-toluenesulfonyl) group (Ts is also the symbol for the element tennessine. However, tennessine is never encountered in organic chemistry, so the use of Ts to represent the tosyl group never causes confusion)

Protecting groups

A protecting group or protective group is introduced into a molecule by chemical modification of a functional group to obtain chemoselectivity in a subsequent chemical reaction, facilitating multistep organic synthesis.

- Boc for the t-butoxycarbonyl group

- Cbz or Z for the carboxybenzyl group

- Fmoc for the fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl group

Multiple bonds

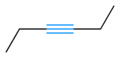

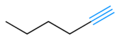

Two atoms can be bonded by sharing more than one pair of electrons. The common bonds to carbon are single, double and triple bonds. Single bonds are most common and are represented by a single, solid line between two atoms in a skeletal formula. Double bonds are denoted by two parallel lines, and triple bonds are shown by three parallel lines.

In more advanced theories of bonding, non-integer values of bond order exist. In these cases, a combination of solid and dashed lines indicate the integer and non-integer parts of the bond order, respectively.

Hex-3-ene has an internal carbon-carbon double bond

Hex-1-ene has a terminal double bond

Hex-3-yne has an internal carbon-carbon triple bond

Hex-1-yne has a terminal carbon-carbon triple bond

Note: in the gallery above, double bonds have been shown in red and triple bonds in blue. This was added for clarity - multiple bonds are not normally coloured in skeletal formulae.

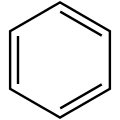

Benzene rings

In recent years, benzene is generally depicted as a hexagon with alternating single and double bonds, much like the structure originally proposed by Kekulé in 1872. As mentioned above, the alternating single and double bonds of "1,3,5-cyclohexatriene" are understood to be a drawing of one of the two equivalent canonical forms of benzene, in which all carbon-carbon bonds are of equivalent length and have a bond order of 1.5.

An alternative representation that emphasizes this delocalization uses a circle, drawn inside the regular hexagon of single bonds. This style, based on one proposed by Johannes Thiele, used to be very common in introductory organic chemistry textbooks and is still frequently used in informal settings. However, because this depiction does not keep track of electron pairs and is unable to show the precise movement of electrons, it has largely been superseded by the Kekuléan depiction in pedagogical and formal academic contexts.

Stereochemistry

Stereochemistry is conveniently denoted in skeletal formulae:[5]

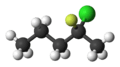

Ball-and-stick model of

(R)-2-chloro-2-fluoropentane-2-Chloro-2-fluoropentane.svg.png)

Skeletal formula of

(R)-2-chloro-2-fluoropentane-2-Chloro-2-fluoropentane.svg.png)

Skeletal formula of

(S)-2-chloro-2-fluoropentane

Skeletal formula of amphetamine, indicating a mixture of two stereoisomers: (R)- and (S)-

The relevant chemical bonds can be depicted in several ways:

- Solid lines represent bonds in the plane of the paper or screen.

- Solid wedges represent bonds that point out of the plane of the paper or screen, towards the observer.

- Hashed wedges or dashed lines (thick or thin) represent bonds that point into the plane of the paper or screen, away from the observer.

- Wavy lines represent either unknown stereochemistry or a mixture of the two possible stereoisomers at that point.

An early use of this notation can be traced back to Richard Kuhn who in 1932 used solid thick lines and dotted lines in a publication. The modern wedges were popularised in the 1959 textbook "Organic Chemistry" by Donald J. Cram and George S. Hammond [6]

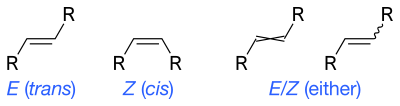

Skeletal formulae can depict cis and trans isomers of alkenes. Wavy single bonds are the standard way to represent unknown or unspecified stereochemistry or a mixture of isomers (as with tetrahedeal stereocenters). A crossed double-bond has been used sometimes; is no longer considered an acceptable style for general use, but may still be required by computer software.[5]

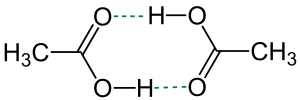

Hydrogen bonds

Hydrogen bonds are generally denoted by dotted or dashed lines. In other contexts, dashed lines may also represent partially formed or broken bonds in a transition state.

References

- ↑ General, Organic, and Biological Chemistry, H. Stephen Stoker 2012

- ↑ This term is ambiguous, because "Kekulé structure" also refers to Kekulé's famous proposal of hexagonal, alternating double-bonds for the structure of benzene.

- ↑ IUPAC Recommendations 1999, Revised Section F: Replacement of Skeletal Atoms

- ↑ Clayden, Jonathan; Greeves, Nick; Warren, Stuart; Wothers, Peter (2001). Organic Chemistry (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-19-850346-0.

- 1 2 J. Brecher (2006). "Graphical representation of stereochemical configuration (IUPAC Recommendations 2006)" (PDF). Pure Appl. Chem. 78 (10): 1897–1970. doi:10.1351/pac200678101897.

- ↑ The Historical Origins of Stereochemical Line and Wedge Symbolism William B. Jensen Journal of Chemical Education 2013 90 (5), 676-677 doi:10.1021/ed200177u

External links

- Drawing organic molecules from chemguide.co.uk