Cape Canaveral Air Force Station

| Cape Canaveral Air Force Station | |

|---|---|

| Part of Patrick Air Force Base | |

|

Cape Canaveral, Florida, United States Near Cocoa Beach in United States | |

| |

| |

Cape Canaveral Air Force Station | |

| Coordinates | 28°29′20″N 80°34′40″W / 28.48889°N 80.57778°WCoordinates: 28°29′20″N 80°34′40″W / 28.48889°N 80.57778°W |

| Type | Air Force Base |

| Area | 1,325 acres (5 km2)[1] |

| Site information | |

| Owner | U.S. Department of Defense |

| Operator | Air Force Space Command |

| Controlled by | 45th Space Wing |

| Open to the public | No |

| Website | http://www.patrick.af.mil |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1940[2] |

| In use | 1948—present |

| Events | Space Race |

Cape Canaveral Air Force Station (CCAFS) (known as Cape Kennedy Air Force Station from 1963 to 1973) is an installation of the United States Air Force Space Command's 45th Space Wing. [2]

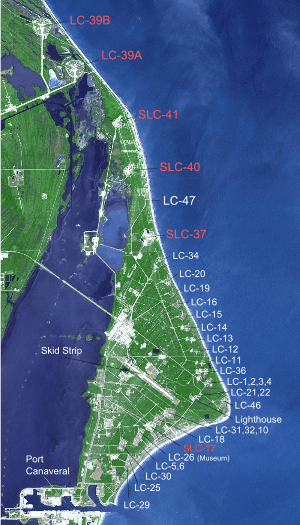

CCAFS is headquartered at the nearby Patrick Air Force Base, and located on Cape Canaveral in Brevard County, Florida, CCAFS. The station is the primary launch head of America's Eastern Range[3] with three launch pads currently active (Space Launch Complexes 37B, 40, and 41). Popularly known as "Cape Kennedy" from 1963 to 1973, and as "Cape Canaveral" from 1949 to 1963 and from 1973 to the present, the facility is south-southeast of NASA's Kennedy Space Center on adjacent Merritt Island, with the two linked by bridges and causeways. The Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Skid Strip provides a 10,000-foot (3,000 m) runway[4] close to the launch complexes for military airlift aircraft delivering heavy and outsized payloads to the Cape.

A number of American space exploration pioneers were launched from CCAFS, including the first U.S. Earth satellite in 1958, first U.S. astronaut (1961), first U.S. astronaut in orbit (1962), first two-man U.S. spacecraft (1965), first U.S. unmanned lunar landing (1966), and first three-man U.S. spacecraft (1968). It was also the launch site for all of the first spacecraft to (separately) fly past each of the planets in the Solar System (1962–1977), the first spacecraft to orbit Mars (1971) and roam its surface (1996), the first American spacecraft to orbit and land on Venus (1978), the first spacecraft to orbit Saturn (2004), and to orbit Mercury (2011), and the first spacecraft to leave the Solar System (1977).

History

The CCAFS area had been used by the United States government to test missiles since 1949, when President Harry S. Truman established the Joint Long Range Proving Ground at Cape Canaveral.[5] The location was among the best in the continental United States for this purpose, as it allowed for launches out over the Atlantic Ocean, and is closer to the equator than most other parts of the United States, allowing rockets to get a boost from the Earth's rotation.

Air Force proving ground

On June 1, 1948, the U.S. Navy transferred the former Banana River Naval Air Station to the U.S. Air Force, with USAF renaming the facility the Joint Long Range Proving Ground (JLRPG) Base on June 10, 1949. On October 1, 1949, the Joint Long Range Proving Ground Base was transferred from the Air Materiel Command to the Air Force Division of the Joint Long Range Proving Ground. On May 17, 1950, the base was renamed the Long Range Proving Ground Base, but three months later was renamed Patrick Air Force Base, in honor of Army Maj. Gen. Mason Patrick.[6] In 1951, the Air Force established the Air Force Missile Test Center.

Early American sub-orbital rocket flights were achieved at Cape Canaveral in 1956.[7] These flights occurred shortly after sub-orbital flights launched from White Sands Missile Range, such as the Viking 12 sounding rocket on February 4, 1955. [8] Following the Soviet Union's successful Sputnik 1 (launched on October 4, 1957), the US attempted its first launch of an artificial satellite from Cape Canaveral on December 6, 1957. However, the rocket carrying Vanguard TV3 blew up on the launch pad.[9]

NASA was founded in 1958, and Air Force crews launched missiles for NASA from the Cape, known then as Cape Canaveral Missile Annex. Redstone, Jupiter, Pershing 1, Pershing 1a, Pershing II, Polaris, Thor, Atlas, Titan and Minuteman missiles were all tested from the site, the Thor becoming the basis for the expendable launch vehicle (ELV) Delta rocket, which launched Telstar 1 in July 1962. The row of Titan (LC-15, 16, 19, 20) and Atlas (LC-11, 12, 13, 14) launch pads along the coast came to be known as Missile Row in the 1960s.

Project Mercury

NASA's first manned spaceflight program was prepared for launch from Canaveral by U.S. Air Force crews. Mercury's objectives were to place a manned spacecraft in Earth orbit, investigate human performance and ability to function in space, and safely recover the astronaut and spacecraft. Suborbital flights were launched by derivatives of the Army's Redstone missile from LC-5; two such flights were made by Alan Shepard on May 5, 1961, and Gus Grissom on July 21. Orbital flights were launched by derivatives of the Air Force's larger Atlas D missile from LC-14. The first American in orbit was John Glenn on February 20, 1962. Three more orbital flights followed through May 1963.

Flight control for all Mercury missions was provided at the Mercury Control Center located at Canaveral near LC-14.

Temporary name change

On November 29, 1963, following the death of President John F. Kennedy, his successor Lyndon B. Johnson issued Executive Order 11129 renaming both NASA's Merrit Island Launch Operations Center and "the facilities of Station No. 1 of the Atlantic Missile Range" (a reference to Canaveral AFB) as the "John F. Kennedy Space Center". He had also convinced Gov. C. Farris Bryant (D-Fla.) to change the name of Cape Canaveral to Cape Kennedy. This resulted in some confusion in public perception, which conflated the two. NASA Administrator James E. Webb clarified this by issuing a directive stating the Kennedy Space Center name applied only to Merrit Island, while the Air Force issued a general order renaming the Air Force Station launch site Cape Kennedy Air Force Station.[10] This name was used through the Gemini and early Apollo programs.

However, the geographical name change proved to be unpopular, owing to the historical longevity of Cape Canaveral (one of the oldest place-names in the United States, dating to the early 1500s). In 1973, both the Air Force Base and the geographical Cape names were reverted to Canaveral after the Florida legislature passed a bill changing the name back that was signed into law by Florida governor Reubin Askew.[11][12]

Gemini and early Apollo

The two-man Gemini spacecraft was launched into orbit by a derivative of the Air Force Titan II missile. Twelve Gemini flights were launched from LC-19, ten of which were manned. The first manned flight, Gemini 3, took place on March 23, 1965. Later Gemini flights were supported by seven unmanned launches of the Agena Target Vehicle on the Atlas-Agena from LC-14, to develop rendezvous and docking, critical for Apollo. Two of the Atlas-Agena vehicles failed to reach orbit on Gemini 6 and Gemini 9, and a mis-rigging of the nosecone on a third caused it to fail to eject in orbit, preventing docking on Gemini 9A. The final flight, Gemini 12, launched on November 11, 1966.

The capabilities of the Mercury Control Center were inadequate for the flight control needs of Gemini and Apollo, so NASA built an improved Mission Control Center in 1963, which it decided to locate at the newly built Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, Texas, rather than at Canaveral or at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland.[13]

The Apollo program's goal of landing a man on the Moon required development of the Saturn family of rockets. The large Saturn V rocket necessary to take men to the Moon required a larger launch facility than Cape Canaveral could provide, so NASA built the Kennedy Space Center located west and north of Canaveral on Merrit Island. But the earlier Saturn I and IB could be launched from the Cape's Launch Complexes 34 and 37. The first four Saturn I development launches were made from LC-34 between October 27, 1961 and March 28, 1963. These were followed by the final test launch and five operational launches from LC-37 between January 29, 1964 and July 30, 1965.

The Saturn IB uprated the capability of the Saturn I, so that it could be used for Earth orbital tests of the Apollo spacecraft. Two unmanned test launches of the Apollo Command/Service Module (CSM), AS-201 and AS-202, were made from LC-34, and an unmanned flight (AS-203) to test the behavior of upper stage liquid hydrogen fuel in orbit from LC-37, between February 26 and August 25, 1966. The first manned CSM flight, AS-204 or Apollo 1, was planned to launch from LC-34 on February 21, 1967, but the entire crew of Gus Grissom, Edward H. White and Roger Chaffee were killed in a cabin fire during a spacecraft test on pad 34 on January 27, 1967. The AS-204 rocket was used to launch the unmanned, Earth orbital first test flight of the Apollo Lunar Module, Apollo 5, from LC-37 on January 22, 1968. After significant safety improvements were made to the Command Module, Apollo 7 was launched from LC-34 to fulfill Apollo 1's mission, using Saturn IB AS-205 on October 11, 1968.

In 1972, NASA deactivated both LC-34 and LC-37. It briefly considered reactivating both for Apollo Applications Program launches after the end of Apollo, but instead modified the Kennedy Space Center launch complex to handle the Saturn IB for the Skylab and Apollo-Soyuz Test Project launches. The LC-34 service structure and umbilical tower were razed, leaving only the concrete launch pedestal as a monument to the Apollo 1 crew. In 2001, LC-37 was recommissioned and converted to service Delta IV launch vehicles.

Subsequent activity

The Air Force chose to expand the capabilities of the Titan launch vehicles for its heavy lift capabilities. The Air Force constructed Launch Complexes 40 and 41 to launch Titan III and Titan IV rockets just south of Kennedy Space Center. A Titan III has about the same payload capacity as the Saturn IB at a considerable cost savings.

Launch Complex 40 and 41 have been used to launch defense reconnaissance, communications and weather satellites and NASA planetary missions. The Air Force also planned to launch two Air Force manned space projects from LC 40 and 41. They were the Dyna-Soar, a manned orbital rocket plane (canceled in 1963) and the USAF Manned Orbital Laboratory (MOL), a manned reconnaissance space station (canceled in 1969).

From 1974–1977 the powerful Titan-Centaur became the new heavy lift vehicle for NASA, launching the Viking and Voyager series of spacecraft from Launch Complex 41. Complex 41 later became the launch site for the most powerful unmanned U.S. rocket, the Titan IV, developed by the Air Force.

With increased use of a leased launch pad by private company SpaceX, the Air Force launch support operations at the Cape are planning for 21 launches in 2014, a fifty percent increase over the 2013 launch rate. SpaceX has reservations for a total of ten of those launches in 2014, with an option for an eleventh.[14]

Unmanned launches at Cape Canaveral

The first United States satellite launch, Explorer 1, was made by the Army Ballistic Missile Agency on February 1, 1958 (UTC) from Canaveral's LC-26A using a Juno I RS-29 missile. NASA's first launch, Pioneer 1, came on October 11 of the same year from LC-17A using a Thor-Able rocket.

Besides Project Gemini, the Atlas-Agena launch complexes LC-12 and LC-13 were used during the 1960s for the unmanned Ranger and Lunar Orbiter programs and the first five Mariner interplanetary probes. The Atlas-Centaur launch complex LC-36 was used for the 1960s Surveyor unmanned lunar landing program and the last five Mariner probes through 1973.

NASA has also launched communications and weather satellites from Launch Complexes 40 and 41, built at the north end of the Cape in 1964 by the Air Force for its Titan IIIC and Titan IV rockets. From 1974–1977 the powerful Titan IIIE served as the heavy-lift vehicle for NASA, launching the Viking and Voyager series of planetary spacecraft and the Cassini–Huygens Saturn probe from LC-41.

Three Cape Canaveral pads are currently operated by NASA and private industry for civilian launches: SLC-41 for the Atlas V and SLC-37B for the Delta IV, both for United Launch Alliance heavy payloads; and SLC-40 for SpaceX Falcon 9 launches to the International Space Station.

NASA's Launch Services Program (LSP) is responsible for oversight of launch operations and countdown management for all unmanned launches at Cape Canaveral which it does not operate.

Boeing X-37B

The Boeing X-37B, a reusable unmanned spacecraft operated by USAF which is also known as the Orbital Test Vehicle (OTV), has been successfully launched four times from Cape Canaveral.[15] All X-37B missions have been launched with Atlas V rockets. Past launch dates for the X-37B spaceplane include April 22, 2010, March 5, 2011, December 11, 2012 and May 20, 2015. The fourth and latest X-37B mission landed at the Kennedy Space Center on May 7, 2017 after 718 days in orbit. The first three X-37B missions all made successful autonomous landings from space to a 15,000 foot runway located at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California which was originally designed for Space Shuttle return from orbit operations.

Facilities

Of the launch complexes built since 1950, several have been leased and modified for use by private aerospace companies. Launch Complex SLC-17 was used for the Delta II Heavy variant, through 2011.[16] Launch Complexes SLC-37 and SLC-41 were modified to launch EELV Delta IV and Atlas V launch vehicles, respectively.[17] These launch vehicles replaced all earlier Delta, Atlas, and Titan rockets. Launch Complex SLC-47 is used to launch weather sounding rockets. Launch Complex SLC-46 is reserved for use by Space Florida.[18]

Launch Complex SLC-40 hosted the first launch of the SpaceX Falcon 9 in June 2010.[19] Falcon 9 launches continued from this complex through 2015, consisting of unmanned Commercial Resupply Services missions for NASA to the International Space Station as well as commercial satellite flights. SpaceX has also leased Launch Complex 39A from NASA and has nearly completed modifying it to accommodate Falcon Heavy and Commercial Crew manned spaceflights to the ISS with their Crew Dragon spacecraft in 2017.[20] SpaceX Landing Zone 1, used to land first stages of Falcon 9 launch vehicles, is located at the site of the former LC-13.

On September 16, 2015, NASA announced that Blue Origin has leased Launch Complex 36 and will modify it as a launch site for their next-generation launch vehicles.[21]

In the case of low-inclination (geostationary) launches the location of the area at 28°27′N put it at a slight disadvantage against other launch facilities situated nearer the equator. The boost eastward from the Earth's rotation is about 406 m/s (908 miles per hour) at Cape Canaveral against about 463 m/s (1,035 miles per hour) at the European Guiana Space Centre in French Guiana.[22]

In the case of high-inclination (polar) launches the latitude does not matter, but the Cape Canaveral area is not suitable because inhabited areas underlie these trajectories; Vandenberg Air Force Base, Cape Canaveral's West coast counterpart, or the smaller Kodiak Launch Complex in Alaska is used instead.

The Air Force Space & Missile Museum is located at LC-26.[23] Hangar AE, located in the CCAFS Industrial Area, collects telemetry from launches all over the USA. NASA's Launch Services Program has three Launch Vehicle Data Centers (LVDC) within that display telemetry real-time for engineers.

National Register of Historic Places

|

Cape Canaveral Air Force Station

Part of Air Force Space Command (AFSPC) | |

| |

| Location | Cape Canaveral, Florida, United States |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 28°29′20″N 80°34′40″W / 28.48889°N 80.57778°W |

| Area | 1,325 acres (5 km2)[1] |

| Built | 1950+[24] |

| Visitation | Not open to the public |

| NRHP Reference # | 84003872[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | April 16, 1984 |

| Designated NHLD | April 16, 1984[25] |

Gallery

|

See also

References

- 1 2 3 National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 "Patrick Air Force Base – FAQ Topic". Patrick Air Force Base. Archived from the original on November 17, 2007.

- ↑ CAST 1999, p. 1-12.

- ↑ "World Aero Data: Cape Cnaveral AFS Skid Strip – XMR". Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ↑ "Factsheets : Evolution of the 45th Space Wing". Archived from the original on June 13, 2011.

- ↑ CAST 1999, p. 1-5.

- ↑ "Cape Canaveral LC5".

- ↑ "Viking".

- ↑ By MILTON BRACKER Special to The New York Times. (1957, Dec 07). Vanguard rocket burns on beach; failure to launch test satellite assailed as blow to U.S. prestige. New York Times (1923-Current File), pp. 1. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/114053516

- ↑ Benson, Charles D.; Faherty, William B. (August 1977). "Chapter 7: The Launch Directorate Becomes an Operational Center - Kennedy's Last Visit". Moonport: A History of Apollo Launch Facilities and Operations. History Series. SP-4204. NASA.

- ↑ "History of Cape Canaveral 1959-Present".

- ↑ Cape Canaveral GNIS page

- ↑ Dethloff, Henry C. (1993). "Chapter 5: Gemini: On Managing Spaceflight". Suddenly Tomorrow Came... A History of the Johnson Space Center. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-1502753588.

- ↑ Klotz, Irene (2014-01-15). "SpaceX Drives Sharp Increase in Projected Launches at Cape". SpaceNews. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- ↑ http://www.af.mil/AboutUs/FactSheets/Display/tabid/224Article/104539/x-37b-orbital-test-vehicle.aspx

- ↑ CAST 1999, p. 1-26.

- ↑ CAST 1999, p. 1-31.

- ↑ CAST 1999, p. 1-35.

- ↑ SpaceX Corp (October 23, 2009). "Dragon/ Falcon 9 Update". SpaceX. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- ↑ Bergin, Chris (18 February 2015). "Falcon Heavy into production as Pad 39A HIF rises out of the ground". NASASpaceFlight. NASASpaceFLight. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ↑ Kenneth Chang (September 16, 2015). "Blue Origin, Jeff Bezos’ Rocket Company, to Launch from Florida". The New York Times. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ "Up, Up, and Away". The Universe: In the Classroom. Astro Society. Retrieved August 11, 2011.

- ↑ CAST 1999, pp. 1–29 to 1–30.

- ↑ "Cape Canaveral Air Force Station". Florida Heritage Tourism Interactive Catalog. Florida's Office of Cultural and Historical Programs. September 23, 2007. Archived from the original on December 14, 2007.

- ↑ Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Archived January 13, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. at National Historic Landmarks Program.

Sources

- "Launch Site Safety Assessment, Section 1.0 Eastern Range General Range Capabilities" (PDF). Research Triangle Institute, Center for Aerospace Technology (CAST), Florida Office. Federal Aviation Administration. March 1999. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. |

- Patrick Air Force Base

- Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Virtual Tour

- Air Force Space and Missile Museum Web site

- "Cape Canaveral Lighthouse Shines Again" article and video interview about the lighthouse

- Aviation: From Sand Dunes to Sonic Booms, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary

- The short film "The Cape (1963)" is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. FL-8-5, "Cape Canaveral Air Station, Launch Complex 17, East end of Lighthouse Road, Cape Canaveral, Brevard, FL"

- The Launch Pads of Cape Canaveral