Canyoning

Canyoning (canyoneering in the U.S. / kloofing in South-Africa / torrentismo in Italian, barranquismo in Spanish) is travelling in canyons using a variety of techniques that may include other outdoor activities such as walking, scrambling, climbing, jumping, abseiling (rappelling), and swimming.

Although hiking down a canyon that is non-technical, (canyon hiking) is often referred to as canyoneering, the terms canyoning and canyoneering are more often associated with technical descents — those that require abseils (rappels) and ropework, technical climbing or down-climbing, technical jumps, and/or technical swims.

Canyoning is frequently done in remote and rugged settings and often requires navigational, route-finding and other wilderness travel skills.

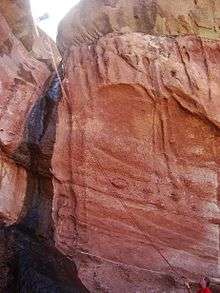

Canyons that are ideal for canyoning are often cut into the bedrock stone, forming narrow gorges with numerous drops, beautifully sculpted walls, and sometimes spectacular waterfalls. Most canyons are cut into limestone, sandstone, granite or basalt, though other rock types are found. Canyons can be very easy or extremely difficult, though emphasis in the sport is usually on aesthetics and fun rather than pure difficulty. A wide variety of canyoning routes are found throughout the world, and canyoning is enjoyed by people of all ages and skill levels.

Canyoning gear includes climbing hardware, static or semi-static ropes, helmets, wetsuits, and specially designed shoes, packs, and rope bags. While canyoneers have used and adapted climbing, hiking, and river running gear for years, more and more specialized gear is invented and manufactured as canyoning popularity increases.

Canyoning around the world

In most parts of the world canyoning is done in mountain canyons with flowing water. The number of countries with established canyoning outfitters is growing yearly, and include:

Africa

- Kenya

- Madagascar

- Mauritius

- Morocco

- Reunion

- South Africa (known as "kloofing")

Asia

- China

- Georgia

- Hong Kong

- Indonesia

- India

- Iran

- Israel

- Japan

- Jordan

- Laos

- Lebanon

- Malaysia

- Nepal

- Philippines

- Sri Lanka

- Taiwan

- Thailand

- Vietnam

Europe

- Albania

- Austria

- Bosnia & Herzegovina

- Bulgaria

- Croatia

- England

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Iceland

- Ireland

- Italy

- Montenegro

- Norway

- Portugal (Azores) (Madeira)

- Romania

- Russia

- Scotland

- Serbia

- Slovenia

- Spain

- Switzerland

- Wales

- Turkey

North America

- Antigua

- Belize

- Canada

- Costa Rica

- Cuba

- Dominica

- Dominican Republic

- El Salvador

- Grenada

- Guadeloupe

- Guatemala

- Honduras

- Jamaica

- Martinique

- Mexico

- Nicaragua

- Panama

- United States

Oceania

South America

In Japan and Taiwan canyoning is called river tracing and typically involves traveling upstream.

In the UK canyoning is now readily available in locations including Scotland and some areas of Cornwall, however the most popular area is canyoning in Wales. It has been described as slightly different from its American counterpart however involves all the traditional methods but in a different climate and location. Most experts who visit Wales for this activity often refer to it as Gorge Walking yet the main concept remains the same.

In the United States, descending mountain canyons with flowing water is sometimes referred to as canyoning, although the term "canyoneering" is more common. Most canyoneering in the United States occurs in the many slot canyons carved in the sandstone found throughout the Colorado Plateau. Outside of the Colorado Plateau, numerous canyoneering opportunities are found in the San Gabriel, Sierra Nevada, Cascade, and Rocky Mountain ranges.

Canyoning in the UK has gained in popularity over recent years. Of all parts of the UK Wales and Scotland are recognized as the best places to try out this activity. In the Welsh language canyoning is called "cerdded ceunant".

Canyoning in Ticino, Switzerland also named the eldorado for canyoning is one of a kind because of its authentic granite rock, crystal green pools and its pleasant mediterranean climate. This region has been popular throughout the whole story of canyoning, back in the days of the pioneers, but only the last few years is gaining an enormous popularity amongst more experienced canyoneers.

Hazards

Canyoning can be dangerous. Escape out the sides of a canyon is often impossible, and completion of the descent is the only possibility. Due to the remoteness and inaccessibility of many canyons, rescue can be impossible for several hours or several days.

High water flow / hydraulics

Canyons with significant water flow may be treacherous and require special ropework techniques for safe travel. Hydraulics, undercurrents, and sieves (or strainers) occur in flowing canyons and can trap or pin and drown a canyoneer. A 1993 accident in Zion National Park, Utah, USA, in which two leaders of a youth group drowned in powerful canyon hydraulics (and the lawsuit which followed) brought notoriety to the sport.[1]

Flash floods

A potential danger of many canyoning trips is a flash flood. A canyon "flashes" when a large amount of precipitation falls in the drainage, and water levels in the canyon rise quickly as the runoff rushes down the canyon. In canyons that drain large areas, the rainfall could be many kilometers away from the canyoners, completely unbeknown to them. A calm or even dry canyon can quickly become a violent torrent due to a severe thunderstorm in the vicinity. Fatalities have occurred as a result of flash floods; in one widely publicized 1999 incident, 21 tourists on a commercial canyoning adventure trip drowned in Saxetenbach Gorge, Switzerland. Authorities in Switzerland have set in the last few years high standards on safety, "Safety in adventures" label is becoming the standard for all companies to prove they are following the standard safety procedures.

Hypothermia and hyperthermia

Temperature related illnesses are also canyoning hazards. In arid desert canyons, heat exhaustion can occur if proper hydration levels are not maintained and adequate steps are not taken to avoid the intense rays of the sun. Hypothermia can be a serious danger in any canyon that contains water, during any time of the year. Wetsuits and drysuits can mitigate this danger to a large degree, but when people miscalculate the amount of water protection they will need, dangerous and sometimes fatal situations can occur. Hypothermia due to inadequate cold water protection is cited as a cause of a 2005 incident in which two college students drowned in a remote Utah canyon.[2]

Keeper potholes

Some canyoneering, especially in sandstone slots, involves escaping from large potholes. Also called "keeper potholes," these features, carved out by falling water at the bottom of a drop in the watercourse, are circular pits that often contain water that is too deep to stand up in and whose walls are too smooth to easily climb out of. Canyoneers use several unique and creative devices to escape potholes, including hooks used for aid climbing attached to long poles and specialized weighted bags that are attached to ropes and tossed over the lip of a pothole.

Very narrow slots

Narrow slot canyons, especially those narrower than humans, present difficult obstacles for canyoners. At times a canyoner is forced to climb up (using chimneying or off-width climbing techniques) to a height where one can comfortably maneuver laterally with pressure on both walls of the canyon. This tends to be strenuous and can require climbing high above the canyon floor, unprotected, for long periods of time. Failure to complete the required moves could result in being trapped in a canyon where rescue is extremely difficult.

Narrow sandstone slot canyons tend to have abrasive walls which rip clothing and gear, and can cause painful skin abrasion as a canyoner moves or slides along them

Education and training

As the sport of canyoneering begins to grow, there are more and more people looking to learn the skills needed to safely descend canyons. There are several reputable organizations that are now offering classes of various forms to the public. Most programs have three or four levels of skills. The first level usually is basic rappelling, rope work, navigation, identification of gear and clothing, and basic rappel setups. The second level deals with anchor building and strategies on how to descend various types of canyons. The third level deals with rescue situations, both self rescues and how to rescue others along with wilderness first aid. An optional course often deals with swift water canyons which entails very different techniques to descend canyons that are flowing with swift water.

References

- ↑ Smith, Christopher; Ray Ring (August 22, 1994). "Whose fault? A Utah canyon turns deadly". High Country News. -- (Requires free registration as of July 18, 2006)

- ↑ "Trip turns deadly for 2 BYU hikers". Salt Lake Tribune.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Canyoning. |