Sardinian language

| Sardinian | |

|---|---|

| Sardu, Limba / Lingua Sarda | |

| Native to | Italy |

| Region | Sardinia |

Native speakers | ~1 million (1993–2007)[1] |

| Dialects |

|

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Limba Sarda Comuna code |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

sc |

| ISO 639-2 |

srd |

| ISO 639-3 |

srd – inclusive code SardinianIndividual codes: sro – Campidanese Sardiniansrc – Logudorese Sardinian |

| Glottolog |

sard1257[2] |

| Linguasphere |

51-AAA-pd & -pe |

| |

|

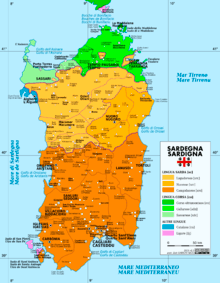

Linguistic map of Sardinia. Sardinian is yellow (Logudorese) and orange (Campidanese). | |

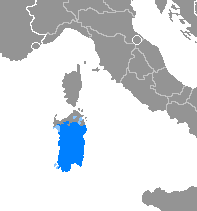

Sardinian (sardu, limba sarda, lingua sarda) or Sard is the primary indigenous Romance language spoken on most of the island of Sardinia (Italy). Of the Romance languages, it is considered one of the closest, if not the closest, to Latin.[3][4] However, it also incorporates a Pre-Latin (Paleo-Sardinian, also known as Nuragic, and, to a much lesser degree, Punic) substratum,[5] and a Byzantine Greek, Catalan, Spanish and Italian superstratum due to the past political membership of the island, first falling into the Hispanic sphere of influence and later towards the Italian one.

Sardinian consists of two mutually intelligible varieties,[6] each with its own literature:[7][8] Campidanese and Logudorese, spoken respectively in the southern half and in the north-central part of Sardinia. Some attempts have been made to introduce a standardized writing system for administrative purposes by combining the two Sardinian varieties, like the LSU (Limba Sarda Unificada, "Unified Sardinian Language") and LSC (Limba Sarda Comuna, "Common Sardinian Language"),[9] but they have not been generally acknowledged by native speakers.[10][11][12]

In 1997 Sardinian, along with all the other languages spoken by the Sardinians, was recognized by a regional law; since 1999, Sardinian is also one of the twelve "historical language minorities" of Italy and protected as such by the national Law no. 482/1999.[13] However, the language is in retreat and UNESCO classifies both main varieties as "definitely endangered";[14] although an estimated 68.4 percent of the islanders have a good oral command of Sardinian.[15] Italian is displacing it nonetheless in many cases, and language ability among children has been estimated to have dropped in fact to around 13 percent.[16][17]

Overview

Now the question arises as to whether Sardinian is to be considered a dialect or a language in its own right. Politically speaking,[18] it is clearly one of the many dialects of Italy, just like the Serbo-Croatian and the Albanian spoken in various villages of Calabria and Sicily. However, from a linguistic point of view, that is a different question. It can be said that Sardinian has no relationship whatsoever with any dialect of mainland Italy; it is an archaic Romance speech with its own distinctive characteristics, showing a very original vocabulary in addition to morphology and syntax rather different from the Italian dialects.[19]— Max Leopold Wagner, La lingua sarda, 1951 – Ilisso, pp. 90–91

Sardinian is considered the most conservative Romance language,[20] and its substratum (Paleo-Sardinian or Nuragic) has also been researched. A 1949 study by Italian-American linguist Mario Pei, analyzing the degree of difference from a language's parent (Latin, in the case of Romance languages) by comparing phonology, inflection, syntax, vocabulary, and intonation, indicated the following percentages (the higher the percentage, the greater the distance from Latin):[21] Sardinian 8%, Italian 12%, Spanish 20%, Romanian 23.5%, Occitan 25%, Portuguese 31%, and French 44%. For example, Latin "Pone mihi tres panes in bertula" (put three loaves of bread [from home] in the bag for me) would be the very similar "Ponemi tres panes in bertula" in Sardinian.[22]

Compared to the mainland Italian lects, Sardinian is virtually incomprehensible for Italians,[12] being actually an autonomous linguistic group.[24][25]

History

Sardinia's relative isolation from mainland Europe encouraged the development of a Romance language preserving traces of its indigenous, pre-Roman language(s). The language is posited to have substratal influences from Paleo-Sardinian language, which some scholars have linked to Basque[26] and Etruscan.[27] Adstratal influences include Catalan, Spanish, and Italian. The situation of Sardinian language with regard to the politically dominant ones did not change until the 1950s.[28][29]

Origins, Prenuragic and Nuragic era

The origins of the Paleo-Sardinian language are currently not known. Research has attempted to discover obscure, indigenous, pre-Romance roots; the root s(a)rd, present in many place names and denoting the island's people, is reportedly from Sherden (one of the Sea Peoples), although this assertion is hotly debated.

In 1984, Massimo Pittau said he found in the Etruscan language the etymology of many Latin words after comparing it with the Nuragic language(s).[27] Etruscan elements, formerly thought to have originated in Latin, would indicate a connection between the ancient Sardinian culture and the Etruscans. According to Pittau, the Etruscan and Nuragic language(s) are descended from Lydian (and therefore Indo-European) as a consequence of contact with Etruscans and other Tyrrhenians from Sardis as described by Herodotus.[27] Although Pittau suggests that the Tirrenii landed in Sardinia and the Etruscans landed in modern Tuscany, his views are not shared by most Etruscologists.

According to Alberto Areddu[30] the Sherden were of Illyrian origin, on the basis of some lexical elements, unanimously acknowledged as belonging to the indigenous Substrate. Areddu asserts that in ancient Sardinia, especially in the most interior area (Barbagia and Ogliastra), the locals supposedly spoke a particular branch of Indo-European. There are in fact some correspondences, both formal and semantic, with the few testimonies of Illyrian (or Thracian) languages, and above all with their claimed linguistical continuer, Albanian. He finds such correlations: sard. eni, enis, eniu 'yew' = alb. enjë 'yew'; sard. urtzula 'clematis' = alb. urth 'ivy'; sard. rethi 'tendril' = alb. rrypthi 'tendril'.[31] Recently he also discovered important correlations with the Balkan bird world.[32]

According to Bertoldi and Terracini, Paleo-Sardinian has similarities with the Iberic languages and Siculian; for example, the suffix ara in proparoxytones indicated the plural. Terracini proposed the same for suffixes in -/àna/, -/ànna/, -/énna/, -/ònna/ + /r/ + a paragogic vowel (such as the toponym Bunnànnaru). Rohlfs, Butler and Craddock add the suffix -/ini/ (such as the toponym Barùmini) as a unique element of Paleo-Sardinian. Suffixes in /a, e, o, u/ + -rr- found a correspondence in north Africa (Terracini), in Iberia (Blasco Ferrer) and in southern Italy and Gascony (Rohlfs), with a closer relationship to Basque (Wagner and Hubschmid). However, these early links to a Basque precursor have been questioned by some Basque linguists.[33] According to Terracini, suffixes in -/ài/, -/éi/, -/òi/, and -/ùi/ are common to Paleo-Sardinian and northern African languages. Pittau emphasized that this concerns terms originally ending in an accented vowel, with an attached paragogic vowel; the suffix resisted Latinization in some place names, which show a Latin body and a Nuragic suffix. According to Bertoldi, some toponyms ending in -/ài/ and -/asài/ indicated an Anatolic influence. The suffix -/aiko/, widely used in Iberia and possibly of Celtic origin, and the ethnic suffix in -/itanos/ and -/etanos/ (for example, the Sardinian Sulcitanos) have also been noted as Paleo-Sardinian elements (Terracini, Ribezzo, Wagner, Hubschmid and Faust).

Linguists Blasco Ferrer (2009, 2010) and Morvan (2009) have attempted to revive a theoretical connection with Basque by linking words such as Sardinian ospile "fresh grazing for cattle" and Basque ozpil; Sardinian arrotzeri "vagabond" and Basque arrotz "stranger"; Gallurese (South Corsican and North Sardinian) zerru "pig" and Basque zerri. Genetic data on the distribution of HLA antigens have suggested a common origin for the Basques and Sardinians.[34]

Since the Neolithic period, some degree of variance across the island's regions is also attested. The Arzachena culture, for instance, suggests a link between the northernmost Sardinian region (Gallura) and southern Corsica that finds further confirmation in the Naturalis Historia by Pliny the Elder. There are also some stylistic differences between north and south Nuragic Sardinia, which may indicate the existence of two other tribal groups (Balares and Ilienses) mentioned by the same Roman author. According to the archeologist Giovanni Ugas,[35] these peoples may have in fact played an important role in shaping the current regional linguistic differences of the island.

Roman period

Although Roman domination, which began in 238 BC, brought Latin to Sardinia, it was unable to completely supplant the pre-Roman Sardinian languages, including Punic, which continued to be spoken until the second century AD. Some obscure Nuragic roots remained unchanged, and in many cases the Latin accepted local roots (like nur, which makes its appearance in nuraghe, Nurra, Nurri and many other toponyms). Barbagia, the mountainous central region of the island, derives its name from the Latin Barbaria, because its people refused cultural and linguistic assimilation for a long time: 50% of toponyms of central Sardinia, particulary in the territory of Olzai, are actually not related to any known language.[36] Besides the place names, on the island there are still a few names of plants, animals and geological formations directly traceable to the ancient Nuragic era.[37] Cicero called the Sardinian rebels latrones mastrucati ("thieves with rough wool cloaks") to emphasize Roman superiority.[38]

During the long Roman domination Latin gradually become however the speech of the majority of the inhabitants of the island.[39] As a result of this process of romanization the Sardinian language is today classified as Romance or neo-Latin, with some phonetic features resembling Old Latin. Some linguists assert that modern Sardinian, being part of the Island Romance group,[23] was the first language to split off from Latin, all others evolving from Latin as Continental Romance.

At that time, the only literature being produced in Sardinia was mostly in Latin: the native (Paleo-Sardinian) and non-native (Punic) pre-Roman languages were then already extinct (the last Punic inscription in Bithia, southern Sardinia, is from the second or third century A.D.[40]). Some engraved poems in ancient Greek and Latin (the two most prestigious languages in the Roman Empire[41]) are to be seen in Viper Cave, Cagliari, ( Grutta 'e sa Pibera in Sardinian, Grotta della Vipera in Italian, Cripta Serpentum in Latin), a burial monument built by Lucius Cassius Philippus (a Roman who had been exiled to Sardinia) in remembrance of his dead spouse Atilia Pomptilla. We also have some religious works by Saint Lucifer and Eusebius, both from Caralis (Cagliari).

Although Sardinia was culturally influenced and politically ruled by the Byzantine Empire for almost five centuries, Greek did not enter the language except for some ritual or formal expressions in Sardinian using Greek structure and, sometimes, the Greek alphabet.[42][43] Evidence for this is found in the condaghes, the first written documents in Sardinian. From the long Byzantine era there are only a few entries but they already provide a glimpse of the sociolinguistical situation on the island in which, in addition to the community's everyday Neo-Latin language, Greek was also spoken by the ruling classes.[44] Some toponyms, such as Jerzu (thought to derive from the Greek khérsos, "untilled"), together with the personal names Mikhaleis, Konstantine and Basilis, demonstrate Greek influence.[44]

As the Muslims conquered southern Italy and Sicily, communications broke down between Constantinople and Sardinia, whose districts became progressively more autonomous from the Byzantine oecumene (Greek: οἰκουμένη). Sardinia was then brought back into the Latin cultural sphere.

Giudicati period

Sardinian was the first Romance language to gain official status, being used by the Giudicati ("Judgeships"), four Byzantine districts often quarreling with each other that became independent political entities after the Arab expansion in the Mediterranean cut the ties between the island and Byzantium. Old Sardinian had a greater number of archaisms and Latinisms than the present language does. While the earlier documents show the existence of an early Sardinian Koine,[45] the language used by the various Judgeships already displayed a certain range of dialectal variation.[29] A special position was occupied by the Giudicato of Arborea, the last Sardinian kingdom to fall to foreign powers, in which a transitional dialect was spoken, that of Middle Sardinian, The Carta de Logu of the Kingdom of Arborea, one of the first constitutions in history drawn up in 1355–1376 by Marianus IV and the Queen, the "Lady Judge" (judikessa in Sardinian, giudicessa in Italian) Eleanor, was written in this transitional variety of Sardinian, and remained in force until 1827.[46][47] It is presumed the Arborean judges attempted to unify the two main Sardinian dialects in order to gain legitimacy and be therefore entitled to rule the entire island.[48]

Dante Alighieri wrote in his 1302–05 essay De vulgari eloquentia that Sardinians Sardinians, not being Italians (Latii) and having no vulgar language of their own, resorted to aping Latin instead.[12][49][50][51][52][53] Dante's view has been dismissed, because Sardinian had evolved enough to be unintelligible to non-islanders. A popular 12th-century verse from the poem Domna, tant vos ai preiada quotes the provençal troubadour Raimbaut de Vaqueiras, saying No t'intend plui d'un Toesco / o Sardo o Barbarì ("I don't understand you any more than I understand a German / or a Sardinian or a Berber");[54][55][56][53] the Tuscan poet Fazio degli Uberti refers to the Sardinians in his poem Dittamondo as una gente che niuno non la intende / né essi sanno quel ch'altri pispiglia ("a people that no one is able to understand / nor do they come to a knowledge of what other peoples say").[57][52][53] The Muslim geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi, who lived in Palermo, Sicily at the court of King Roger II, wrote in his work "Kitab nuzhat al-mushtaq fi'khtiraq al-'afaq" ("The book of pleasant journeys into faraway lands" or, simply, "The book of Roger") that "Sardinia is large, mountainous, poorly provided with water, two hundred and eighty miles long and one hundred and eighty long from west to east. [...] Sardinians are ethnically Rum Afāriqah (Latins of Africa) like the Berbers; they shun contacts with all the other Rum (Latin) nations and are people of purpose and valiant that never leave the arms".[58][59]

The literature of this period primarily consists of legal documents, besides the aforementioned Carta de Logu. The first document containing Sardinian elements is a 1063 donation to the abbey of Montecassino signed by Barisone I of Torres.[60] Other documents are the Carta Volgare (1070–1080) in Campidanese, the 1080 Logudorese Privilege,[61] the 1089 Donation of Torchitorio (in the Marseille archives),[62] the 1190–1206 Marsellaise Chart (in Campidanese)[63] and an 1173 communication between the Bishop Bernardo of Civita and Benedetto, who oversaw the Opera del Duomo in Pisa.[64] The Statutes of Sassari are written in Logudorese.[65]

Aragonese period – Catalan influence

The 1297 feoffment of Sardinia by Pope Boniface VIII led to the creation of the Aragonese Kingdom of Sardinia and a long period of war between the Aragonese and Sardinians, ending with a Catalan victory at Sanluri in 1409 and the renunciation of any succession right signed by William III of Narbonne in 1420.[66] During this period the clergy adopted Catalan as their primary language, relegating Sardinian to a secondary status. According to attorney Sigismondo Arquer (Cagliari, 1530 – Toledo, 4 giugno 1571), author of Sardiniae brevis historia et descriptio in Sebastian Münster's Cosmographia Universalis, Sardinian prevailed in rural areas and Catalan was spoken in the cities, where the ruling class eventually became bilingual in both languages; Alghero is still a Catalan-speaking enclave on Sardinia to this day.[67]

The long-lasting war and the so-called Black Death had a devastating effect on the island, depopulating large parts of it. People from the neighbouring island of Corsica began to settle in the northern Sardinian coast, leading to the birth of the Tuscan-sounding Sassarese and Gallurese.[68][69]

Despite Catalan being widely spoken and written on the island at this time (leaving a lasting influence in Sardinian), there are some written records of Sardinian. One is the 15th-century Sa Vitta et sa Morte, et Passione de sanctu Gavinu, Brothu et Ianuariu, written by Antòni Canu (1400–1476) and published in 1557: Tando su rey barbaru su cane renegadu / de custa resposta multu restayt iradu / & issu martiriu fetit apparigiare / itu su quale fesit fortemente ligare / sos sanctos martires cum bonas catenas / qui li segaant sos ossos cum sas veinas / & totu sas carnes cum petenes de linu ... . Rimas Spirituales, by Hieronimu Araolla, "glorif[ied] and enrich[ed] Sardinian, our language" (magnificare et arrichire sa limba nostra sarda) as Spanish, French and Italian poets had done for their languages (la Deffense et illustration de la langue françoyse and il Dialogo delle lingue).[28][70] Antonio Lo Frasso, a poet born in Alghero[71] (a city he remembered fondly)[72] who spent his life in Barcelona, wrote lyric poetry in Sardinian:[73] ... Non podende sufrire su tormentu / de su fogu ardente innamorosu. / Videndemi foras de sentimentu / et sensa una hora de riposu, / pensende istare liberu e contentu / m'agato pius aflitu e congoixosu, / in essermi de te senora apartadu, / mudende ateru quelu, ateru istadu ....

Habsburg period – Spanish influence

Through the marriage of Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon in 1469 and, later in 1624, the reorganization of the monarchy led by the Count-Duke of Olivares, Sardinia would progressively leave the exclusive Aragonese cultural sphere in favour of a broader Spanish one. Spanish was perceived as an elitist language, gaining ground among the ruling classes; Sardinian retained much of its importance, being the only language the rural people spoke.[74][75] In "Legendariu de Santas Virgines, et Martires de Iesu Christu", the Orgolese priest Ioan Matheu Garipa called Sardinian the closest living relative of classical Latin: Las apo voltadas in sardu menjus qui non in atera limba pro amore de su vulgu [...] qui non tenjan bisonju de interprete pro bi-las decrarare, et tambene pro esser sa limba sarda tantu bona, quanta participat de sa latina, qui nexuna de quantas limbas si plàtican est tantu parente assa latina formale quantu sa sarda. Spanish had a profound lexical influence on Sardinian nonetheless, especially in those words related to the role that the Spanish had in the vast Habsburg Empire as the language of the Court[76] and in the American and Philippine colonies. Most Sardinian authors were well-versed in Spanish, so much so that Vicente Bacallar y Sanna was one of the founders of the Real Academia Española,[77] and used to write in both Spanish and Sardinian until the 19th century; a notable exception was Pedro Delitala (1550–1590), who decided to write in Italian instead.[71][78]

A 1620 proclamation is in the Bosa archives.[79]

Savoyard period and Kingdom of Italy

The War of the Spanish Succession gave Sardinia to Austria, whose sovereignty was confirmed by the 1713–14 treaties of Utrecht and Rastatt. In 1717 a Spanish fleet reoccupied Cagliari, and the following year Sardinia was ceded to Victor Amadeus II of Savoy in exchange for Sicily. This transfer would not initially entail any social nor linguistic changes, though: Sardinia would still retain for a long time its Hispanic character, so much so that only in 1767 were the Aragonese and Spanish dynastic symbols replaced by the Savoyard cross.[80]

During the Savoyard period, a number of essays written by philologist Matteo Madau[81][82] and professor (and senator) Giovanni Spano attempted to establish a unified orthography based on Logudorese, just like Florentine would become the basis for Italian.[83] In 1811, Vincenzo Raimondo Porru published the first essay on the Southern Sardinian grammar[84] and in 1832 the first Sardinian-Italian dictionary as well.[85]

However, the Savoyard government imposed Italian on Sardinia in July 1760,[86][87][88][89] for reasons related more to the Savoyard need of drawing the island away from the Spanish influence than for Italian nationalism, which would be later pursued by the King Charles Albert.[90][91] At the time, Italian was a foreign language to Sardinians.[92]

Carlo Baudi di Vesme (Cuneo, 1809 – Turin, 1877) claimed that the suppression of Sardinian and the imposition of Italian was desirable in order to make the islanders "civilized" Italians,[93] importing solely Italian-speaking teachers from other regions, and Piedmontese cartographers replaced many Sardinian place names with Italian ones. Despite the assimilation policy the anthem of the Savoyard Kingdom of Sardinia was the Hymnu Sardu Nationale (Sardinian National Anthem), or Cunservet Deus su Re (God save the King), with Sardinian lyrics first in Campidanese and then Logudorese.[94]

During the mobilization for World War I, the Italian Army compelled all Sardinians to enlist as Italian subjects and established the Sassari Infantry Brigade on 1 March 1915 at Tempio Pausania and Sinnai. Unlike the other infantry brigades of Italy, Sassari's conscripts were only Sardinians (including many officers). It is the only unit in Italy with an anthem in a language other than Italian: Dimonios ("Devils"), by Luciano Sechi. Its title derives from Rote Teufel (German for "red devils"). However, compulsory military service played a role in language shift.

Under Fascism all languages other than Italian were banned, including Sardinia's improvised poetry competitions,[95][96][97] and surnames were changed to sound more Italian.[98] During this period, the Sardinian Hymn of the Piedmontese Kingdom was a chance to use a regional language without penalty; as a royal tradition, it could not be forbidden.

Present

The emphasis on monolingual (Italian-only) policies and assimilation has continued after World War II, with historical sites and ordinary objects renamed in Italian.[99] The Ministry of Public Education reportedly requested that the Sardinian teachers be put under surveillance.[100] The rejection of the indigenous language, along with a rigid model of Italian-language education[101], corporal punishment and shaming, led to poor schooling for Sardinians. Even now, Sardinia currently has the highest rate of school and university drop-out in Italy.[102]

There have been many campaigns, often expressed in the form of political demands, to give Sardinian equal status with Italian as a means to promote cultural identity.[103] Following tensions and claims of the Sardinian nationalist movement for concrete cultural and political autonomy, including the recognition of the Sardinians as an ethnic and linguistic minority, three separate bills were presented to the Regional Council in the '80s.[28] A survey conducted in 1984 (cited in Pinna Catte's work, 1992[104]) showed that many Sardinians had a positive attitude towards bilingual education (22% wanted Sardinian to be compulsory in Sardinian schools, while 54.7% would prefer to see teaching in Sardinian as optional); this consensus remains strong to this day. A further survey in 2008 reported that more than half of the interviewees, 57.3%, are in favour of the introduction of Sardinian into schools alongside Italian.[105]

During the 1990s, Sardinian, Albanian, Catalan, German, Greek, Slovenian, Croatian, French, Franco-Provençal, Friulian, Ladin and Occitan were formally recognized as minority languages by Law no. 482/1999.[106] Nevertheless, in many Italian libraries and universities books about the Sardinian language are still classified as Linguistica italiana (Italian linguistics), Dialetti italiani (Italian dialects) or Dialettologia italiana (Italian dialectology).[107][108] Sardinian is considered an "Italian dialect" by some[109] (even at the institutional level[110][111]) and it has been stigmatized as indicative of a lack of education;[112][113] it is still associated by many with shame, backwardness and provincialism.[114] For instance, some Sardinians call the language sa limba de su famine / sa lingua de su famini, literally translating into English as "the language of hunger" (i.e. the language of the poor), regarding it as a stigma of a poverty-stricken, rural, and underprivileged life.

Besides, a number of other factors like a considerable immigration flow from mainland Italy, the interior rural exodus to urban areas, where Sardinian is spoken by a lower percentage of the population[115] and the use of Italian as a prerequisite for jobs and social advancement actually hinder any policy set up to promote the language.[17][116][117] Therefore, UNESCO classifies Sardinian as "definitely endangered", because "many children learn the language, but some of them cease to use it throughout the school years".[118]

At present, language use is far from stable:[28] reports show that, while an estimated 68 percent of the islanders have a good oral command of Sardinian, language ability among the children drops to around 13 percent, if not even less;[17][119][120] some linguists, like Mauro Maxia, cite the low number of Sardinian-speaking children as indicative of language decline, calling Sardinia "a case of linguistic suicide".[16] Most of the younger generation, although they do understand some Sardinian, is actually Italian monolingual and monocultural,[17] speaking a Sardinian-influenced dialect of Italian[121][28][122] that is often nicknamed italiànu porcheddìnu ("pig Italian", meaning more or less "broken Italian") by many native Sardinian speakers.[123] Today, most people who speak Sardinian on an everyday basis live mainly in country-side areas, like the Barbagia region.[124][125]

A bill proposed by former prime minister Mario Monti's cabinet would have lowered Sardinian's protection level,[126] distinguishing between languages protected by international agreements (German, Slovenian, French and Ladin) and indigenous languages. This bill, which was not implemented (Italy, along with France and Malta,[127] has signed but not ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages),[128][129] triggered a reaction on the island.[130][131][132][133] Students have expressed an interest in taking all (or part) of their exit examinations in Sardinian.[134][135][136][137][138][139][140][141][142][143]

In response to a 2013 Italian initiative to remove bilingual signs, a group of Sardinians began a virtual campaign on Google Maps to replace Italian place names with the original Sardinian names. After about one month, Google changed the place names back to Italian.[144][145][146] After a signature campaign,[147] it has been made possible to change the language setting on Facebook from any language to Sardinian.[148][149][150][151] It is also possible to switch to Sardinian even in Telegram[152][153] and a couple of other apps, like Vivaldi, F-Droid, OsmAnd, Notepad++, Stellarium[154] etc. In the 1990s, there was a resurgence of Sardinian-language music, ranging from the more traditional genres (cantu a tenore, cantu a chiterra, gozos etc.) to rock (Kenze Neke, Askra, Tzoku, Tazenda etc.) and even hip hop and rap (Dr. Drer e CRC Posse, Quilo, Sa Razza, Malam, Menhir, Stranos Elementos, Randagiu Sardu, Futta etc.), and with artists who use the language as a means to promote the island and address its long-standing issues and the new challenges.[155][156][157][158] There are also a few films (like Su Re, Bellas Mariposas, Treulababbu, Sonetaula etc.) dubbed in Sardinian,[159] and some others (like Metropolis) provided with subtitles in the language.[160]

In 2015, all the political parties in the Sardinian regional council have reached an agreement involving a series of amendments to the old 1997 law in order to introduce the optional teaching of the language in Sardinia's schools;[161][162][163] as of now, this law has yet to be approved. Although there is still not an option to teach Sardinian on the island itself, let alone in Italy, some language courses are instead sometimes available in Germany (Universities of Stuttgart, Munich, Tübingen, Mannheim[164] etc.), Spain (University of Girona)[165] and Czech Republic (Brno university).[166][167] Shigeaki Sugeta also taught Sardinian to his students of Romance languages at the Waseda University in Tokyo, Japan.[168][169][170][171]

At present, the Sardinian-speaking community is the least protected one in Italy, despite being the largest minority language group officially recognized by the state.[29][173] In fact the language, which is receding in all domains of use, is still not given access to any field of public life,[17] such as education (Italian–Sardinian bilingualism is still frowned upon,[16][136][174][175] while the local universities do not play pretty much any role whatsoever in supporting the language[176][177][178]), politics (with the exception of some nationalist groups[179]), justice, administrative authorities and public services, media,[180][181][182] and cultural,[183] ecclesiastical,[184][185] economic and social activities, as well as facilities. According to a 2017 report on the digital language diversity in Europe, Sardinian appears to be particularly vital on social media as part of many people's everyday life for private use, but such vitality does not still translate into a strong and wide availability of Internet media for the language.[186] In 2017, a 60-hour Sardinian language course has been introduced for the first time in Sardinia and Italy at the University of Cagliari, although such a course was already available in other universities abroad.[187]

In 2015, the Council of Europe commented on the status of national minorities in Italy, regrettably noting the à la carte approach of the Italian state towards them with the exception of the German, French and Slovenian languages, where Italy has been forced to apply full bilingualism due to international agreements. Despite the formal recognition from the Italian state, Italy does not in fact collect any information on the ethnic and linguistic composition of the population and there is virtually no print and broadcasting media exposure in politically or numerically weaker minorites like Sardinian. Moreover, the resources allocated to cultural projects like bilingual education, which lacks a consistent approach, are largely insufficient to meet "even the most basic expectations".[188][189][190][191]

With things being the way they are now, Sardinian has low prestige[17] and is relegated to little more than highly localised levels of interaction.[17] With a solution to the Sardinian question being unlikely to be found anytime soon,[28] the language is becoming highly endangered.[176]

Phonology

All dialects of Sardinian have phonetic features that are relatively archaic compared to other Romance languages. The degree of archaism varies, with the dialect spoken in the Province of Nuoro being considered the most conservative. Medieval evidence indicates that the language spoken on Sardinia and Corsica at the time was similar to modern Nuorese Sardinian. The other dialects are thought to have evolved through Catalan, Spanish and later Italian influences.

The examples listed below are from the Logudorese dialect:

- The Latin short vowels [i] and [u] have preserved their original sound; in Italian, Spanish and Portuguese they became [e] and [o], respectively (for example, siccus > sicu, "dry" (Italian secco, Spanish and Portuguese seco).

- Preservation of the plosive sounds [k] and [ɡ] before front vowels [e] and [i] in many words; for example, centum > kentu, "hundred"; decem > dèke, "ten" and gener > gheneru, "son-in-law" (Italian cento, dièci, genero with [tʃ] and [dʒ]).

- Absence of diphthongizations found in other Romance languages; for example, potest > podest, "he can" (Italian può, Spanish puede, Portuguese pode); bonus > bónu, "good" (Italian buono, Spanish bueno, Portuguese bom)

Sardinian contains the following phonetic innovations:

- Change of the Latin -ll- into a retroflex [ɖɖ], shared with Sicilian and Southern Corsican; for example, corallus > coraddu, "coral" and villa > bidda, "village, town"

- Similar changes in the consonant clusters -ld- and -nd-: soldus > [ˈsoɖ.ɖu] (money), abundantia > [ab.buɳ.ˈɖan.tsi.a] (abundance)

- Evolution of pl-, fl and cl into pr, fr and cr, as in Portuguese and Galician; for example, platea > pratza, "plaza" (Portuguese praça, Galician praza, Italian piazza), fluxus > frúsciu, "flabby" (Portuguese and Galician frouxo) and ecclesia > cresia, "church" (Portuguese igreja, Galician igrexa and Italian chiesa)

- Metathesis such as abbratzare > abbaltzare (to embrace)

- Vowel prothesis before an initial r in Campidanese, similar to Basque and Gascon: rex > urrei = re, gurrèi (king); rota > arroda (wheel) (Gascon arròda); rivus > Sardinian and Gascon arríu (river)

- Vowel prothesis in Logudorese before an initial s followed by consonant, as in the Western Romance languages: scriptum > iscrítu (Spanish escrito, French écrit), stella > isteddu, "star" (Spanish estrella, French étoile)

- Except for the Nuorese dialects, intervocalic Latin single voiceless plosives [p, t, k] became voiced approximant consonants. Single voiced plosives [b, d, ɡ] were lost: [t] > [d] (or its soft counterpart, [ð]): locus > [ˈlo.ɡu] (Italian luògo), caritas > ['ka.ri.tas] (It. carità). This also applies across word boundaries: porcus (pig), but su borku (the pig); domu (house), but sa omu (the house). Such sound changes have become grammaticalised, making Sardinian an initial mutating language with similarities in this to the Celtic Languages.

Although the latter two features were acquired during Spanish rule, the others indicate a deeper relationship between ancient Sardinia and the Iberian world; the retroflex d, l and r are found in southern Italy, Tuscany and Asturias, and were probably involved in the palatalization process of the Latin clusters -ll-, pl-, cl- (-ll- > Spanish and Catalan -ll- [ʎ], Gascon -th [c]; cl- > Galician-Portuguese ch- [tʃ], Ital. chi- [kj]).

According to Eduardo Blasco Ferrer, Sardinian has the following phonemes:

Vowels

The five vowels /a/ /e/ /i/ /o/ /u/, without length differentiation. In Campidanesu, there are 7 vowels, with open è and ò having developed phonemic status.

Consonants

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m /m/ | n /n/ | nny /ɲ/ | |||||

| Plosive | p /p/ b /b/ | t /t/ d /d/ | dd /ɖ/ | k /k/ g /ɡ/ | ||||

| Affricate | tz /ts/ z /dz/ | ch, c, (ts) /tʃ/ g /dʒ/ | ||||||

| Fricative | b [β] | f /f/ v /v/ | (th /θ/) d [ð] | s, ss /s/ s /z/ | sc /ʃ/ x /ʒ/ | g [ɣ] | ||

| Tap | r /ɾ/ | |||||||

| Trill | rr /r/ | |||||||

| Lateral | l /l/ | |||||||

| Approximant | j /j/ |

There are three series of plosives or corresponding approximants:

- Voiceless stops derive from their Latin counterparts in composition after another stop. They are reinforced (double) in initial position, but this reinforcement is not written because it does not produce a different phoneme.

- Double voiced stops (after another consonant) derive from their Latin equivalents in composition after another stop.

- Weak voiced "stops", sometimes transcribed ⟨β, δ, ğ⟩ (approximants [β, ð, ɣ] after vowels, as in Spanish), derive from single Latin stops (voiced or voiceless).

In Cagliari and neighboring dialects, the soft [d] is assimilated to the rhotic consonant [ɾ]: digitus > didu = diru (finger).

The double-voiced retroflex stop /ɖɖ/ (written dd) derives from the former retroflex lateral approximant /ɭɭ/.

Fricatives

- The labiodentals /f/ (sometimes pronounced [ff] or [v] in initial position) and /v/

- Latin initial v becomes b (vipera > bibera, "viper")

- In central Sardinia the sound /f/ disappears, akin to the /f/ > /h/ change in Gascon and Spanish.

- Latin initial v becomes b (vipera > bibera, "viper")

- [θ], written th (as in the English thing, the voiceless dental fricative), is a restricted dialectal variety of the phoneme /ts/.

- /s/

- /ss/: For example, ipsa > íssa

- /ʃ/: Pronounced [ʃ] at the beginning of a word, otherwise [ʃʃ] = [ʃ.ʃ], and is written sc(i/e). The voiced equivalent, [ʒ], is often spelled with the letter x.

Affricates

- /ts/ (or [tts]), a denti-alveolar affricate consonant written tz, corresponds to Italian z or ci.

- /dz/ (or [ddz]), written z, corresponds to Italian gi- or ggi- respectively.

- /tʃ/, written c(i/e) or ç (also written ts in loanwords)

- /ttʃ/

- /dʒ/, written g(e/i) or j

Nasals

- /m/, /mm/

- /n/, /nn/

- /ɲɲ/, written nny (the palatal nasal for some speakers or dialects, although for most the pronunciation is [nːj])

Liquids

Some permutations of l and r are seen; in most dialects, a preconsonant l (for example, lt or lc) becomes r: Latin "altum" > artu, marralzu = marrarzu, "rock".

In palatal context, Latin l changed into [dz], [ts], [ldz] [ll] or [dʒ], rather than the [ʎ] of Italian: achizare (Italian accigliare), *volia > bòlla = bòlza = bòza, "wish" (Italian vòglia), folia > fogia = folla = foza, "leaf" (Italian foglia), filia > filla = fidza = fiza, "daughter" (Italian figlia).

Grammar

Sardinian's distinctive features are:

- The plural marker is -s (from the Latin accusative plural), as in the Western Romance languages French, Occitan, Catalan, Spanish, Portuguese and Galician): sardu, sardus, "sardinian"; pudda, puddas, "hen"; margiane, margianes, "fox". In Italo-Dalmatian languages (such as Italian) or Eastern Romance languages (such as Romanian), the plural ends with -i or -e.

- Sardinian uses a definite article derived from the Latin ipse: su, sa, plural sos, sas (Logudorese) and is (Campidanese). Such articles are common in Balearic Catalan, and were common in Gascon.

- A periphrastic construction of "have to" (late Latin habere ad) is used for the future: ap'a istàre < apo a istàre "I will stay", Vulgar Latin 'habeo ad stare' (as in the Portuguese hei de estar, but here as periphrasis for estarei). Other Latin languages have realisations of the alternative Vulgar Latin 'stare habeo', Italian "starò", Spanish "estaré".

- For prohibitions, a negative form of the subjunctive is used: no bengias!, "don't come!" (compare Spanish no vengas and Portuguese não venhas, classified as part of the affirmative imperative mood).

Varieties

Sardinia has historically had a small population scattered across isolated cantons. The Sardinian language is traditionally divided by scholars into two macro-varieties: Logudorese (su sardu logudoresu), spoken in the north, and Campidanese (su sardu campidanesu), spoken in the south. They differ primarily in phonetics, which does not hamper intelligibility.[6] Logudorese is considered the more conservative dialect, with the Nuorese subdialect (su sardu nugoresu) being the most conservative of all. It has retained the classical Latin pronunciation of the stop velars (kena versus cena, "supper"), the front middle vowels (compare Campidanese iotacism, probably from Byzantine Greek)[192] and assimilation of close-mid vowels (cane versus cani, "dog" and gattos versus gattus, "cats"). Labio-velars become plain labials (limba versus lingua, "language" and abba versus acua, "water"). I is prosthesized before consonant clusters beginning in s (iscala versus Campidanese scala, "stairway" and iscola versus scola, "school"). An east-west strip of small villages in central Sardinia speaks a transitional dialect (Sardu de mesania) between Logudorese and Campidanese. Examples include is limbas (the languages) and is abbas (the waters). Campidanese is the dialect spoken in the southern half of Sardinia (including Cagliari, the metropolis of the Roman province), influenced by Rome, Carthage, Costantinople and Late Latin. Examples include is fruminis (the rivers) and is domus (the houses).

Sardinian is the language of most Sardinian communities. However, in a significant number of Sardinian communities (amounting to 20% of the Sardinian population) Sardinian is not spoken as the native and primary language.[29][6] Two Sardinian–Corsican transitional languages (Gallurese and Sassarese) are spoken in the northernmost part of Sardinia,[193] although some Sardinian is also understood by the majority of people living there (73,6% in Gallura and 67,8% in the Sassarese-speaking subregion). Sassari, the second-largest city on Sardinia and the main center of the northern half of the island (cabu de susu in Sardinian, capo di sopra in Italian), is located there. There are also two language islands, the Catalan Algherese-speaking community from the inner city of Alghero (northwest Sardinia) and the Ligurian-speaking towns of Carloforte, in San Pietro Island, and Calasetta in Sant'Antioco island (south-west Sardinia).[193]

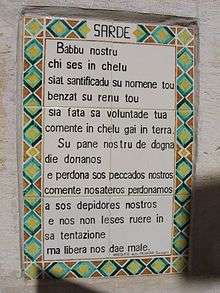

Sample of text

| English | Logudorese Sardinian | Transitional Mesanìa dialect | Campidanese Sardinian |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Our Father in heaven, |

Babbu nostru chi ses in chelu, |

Babbu nostru chi ses in celu, |

Babbu nostu chi ses in celu, |

See also

- Sardinia

- Sardinians

- Paleo-Sardinian language

- Southern Romance

- Dialects of Sardinian: Logudorese, Campidanese

- Non-Sardinian dialects spoken on Sardinia: Sassarese, Gallurese, Algherese, Tabarchino

Notes

- ↑ Sardinian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

Campidanese Sardinian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

Logudorese Sardinian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) - ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Sardinian". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ L'Aventure des langues en Occident , Henriette Walter, Le Livre de poche, Paris, 1994, p. 174

- ↑ Romance languages, Rebecca Posner, Marius Sala. Encyclopedia Britannica

- ↑ Mele, Antonio. Termini prelatini della lingua sarda tuttora vivi nell'uso. Edizioni Ilienses, Olzai

- 1 2 3 Sardinian intonational phonology: Logudorese and Campidanese varieties, Maria Del Mar Vanrell, Francesc Ballone, Carlo Schirru, Pilar Prieto

- ↑ "Sardegna Cultura – Lingua sarda – Il sardo". Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "Sardegna Cultura – Lingua sarda – Letteratura". Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "Sardegna Cultura – Lingua sarda – Limba sarda comuna". Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ Oppo, Anna. Le lingue dei sardi, p. 89

- ↑ La standardizzazione del sardo, oppure: Quante lingue standard per il sardo? E quali? - Matthea Wilsch, Universität Stuttgart, Institut für Linguistik/Romanistik

- 1 2 3 Sardinian Language, Rebecca Posner, Marius Sala. Encyclopedia Britannica

- ↑ "Legge 482". Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger", UNESCO

- ↑ Oppo, Anna. Le lingue dei sardi, p. 7

- 1 2 3 "La situazione sociolinguistica della Sardegna settentrionale di Mauro Maxia". Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Sardinian language use survey, 1995". Euromosaic. To access the data, click on List by languages, Sardinian, then scroll to "Sardinian language use survey".

- ↑ It is to be noted on that matter that Wagner would conduct academic research in 1951; Sardinian would have waited another forty years to be politically recognized, at least formally, as a minority language in Italy.

- ↑ Original version (in Italian): Sorge ora la questione se il sardo si deve considerare come un dialetto o come una lingua. È evidente che esso è, politicamente, uno dei tanti dialetti dell’Italia, come lo è anche, p. es., il serbo-croato o l’albanese parlato in vari paesi della Calabria e della Sicilia. Ma dal punto di vista linguistico la questione assume un altro aspetto. Non si può dire che il sardo abbia una stretta parentela con alcun dialetto dell’italiano continentale; è un parlare romanzo arcaico e con proprie spiccate caratteristiche, che si rivelano in un vocabolario molto originale e in una morfologia e sintassi assai differenti da quelle dei dialetti italiani.

- ↑ Contini & Tuttle, 1982: 171; Blasco Ferrer, 1989: 14

- ↑ Pei, Mario (1949). Story of Language. ISBN 03-9700-400-1.

- ↑ Sardegna, isola del silenzio, Manlio Brigaglia

- 1 2 Koryakov Y.B. Atlas of Romance languages. Moscow, 2001

- ↑ De Mauro, Tullio. L'Italia delle Italie, 1979, Nuova Guaraldi Editrice, Florence, 89

- ↑ Minoranze Linguistiche, Fiorenzo Toso, Treccani

- ↑ Eduardo Blasco Ferrer, ed. 2010. Paleosardo: Le radici linguistiche della Sardegna neolitica (Paleosardo: The Linguistic Roots of Neolithic Sardinian). De Gruyter Mouton

- 1 2 3 "Massimo Pittau – La lingua dei Sardi Nuragici e degli Etruschi". Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Rebecca Posner, John N. Green (Editors), Trends in Romance Linguistics and Philology: Bilingualism and Linguistic Conflict in Romance, pp. 271–294

- 1 2 3 4 Minoranze linguistiche, Sardo. Ministero della Pubblica Istruzione

- ↑ Le Origini "albanesi" della civiltà in Sardegna, Naples, 2007

- ↑ Due nomi di piante che ci legano agli albanesi, Alberto Areddu. L'enigma della lingua albanese

- ↑ Uccelli nuragici e non nella Sardegna di oggi, Seattle 2016

- ↑ Trask, L. The History of Basque Routledge: 1997 ISBN 0-415-13116-2

- ↑ Arnaiz-Villena A, Rodriguez de Córdoba S, Vela F, Pascual JC, Cerveró J, Bootello A. – HLA antigens in a sample of the Spanish population: common features among Spaniards, Basques, and Sardinians. – Hum Genet. 1981;58(3):344-8.

- ↑ Giovanni Ugas – L'alba dei Nuraghi (2005) pg.241

- ↑ Wolf H. J., 1998, Toponomastica barbaricina, p.20 Papiros publisher, Nuoro

- ↑ Wagner M.L., D.E.S. – Dizionario etimologico sardo, DES, Heidelberg, 1960–64

- ↑ "Cicero: Pro Scauro". Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ Casula, Francesco Cesare (1994). La Storia di Sardegna. Sassari, it: Carlo Delfino Editore. ISBN 978-88-7138-084-1. p.110

- ↑ Barreca F.(1988), La civiltà fenicio-punica in Sardegna, Carlo Delfino Editore, Sassari

- ↑ Cum utroque sermone nostro sis paratus. Svetonio, De vita Caesarum, Divus Claudius, 42

- ↑ M. Wescher e M. Blancard, Charte sarde de l’abbaye de Saint-Victor de Marseille écrite en caractères grecs, in "Bibliothèque de l’ École des chartes", 35 (1874), pp. 255–265

- ↑ Un’inedita carta sardo-greca del XII secolo nell’Archivio Capitolare di Pisa, di Alessandro Soddu – Paola Crasta – Giovanni Strinna

- 1 2 Giulio Paulis, Lingua e cultura nella Sardegna Bizantina, Sassari, 1983

- ↑ Salvi, Sergio. Le lingue tagliate: storia delle minoranze linguistiche in Italia, Rizzoli, 1975, pp.176-177

- ↑ La Carta de Logu, La Costituzione Sarda

- ↑ "Carta de Logu (original text)". Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ Barisone II of Arborea, G. Seche, L'incoronazione di Barisone "Re di Sardegna" in due fonti contemporanee: gli Annales genovesi e gli Annales pisani, Rivista dell'Istituto di storia dell'Europa mediterranea, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, n°4, 2010

- ↑ Dantis Alagherii De Vulgari Eloquentia Liber Primus, The Latin Library: Sardos etiam, qui non Latii sunt sed Latiis associandi videntur, eiciamus, quoniam soli sine proprio vulgari esse videntur, gramaticam tanquam simie homines imitantes: nam domus nova et dominus meus locuntur. (Lib. I, XI, 7)

- ↑ De Vulgari Eloquentia (English translation)

- ↑ De Vulgari Eloquentia 's Italian paraphrase by Sergio Cecchini

- 1 2 Marinella Lőrinczi, La casa del signore. La lingua sarda nel De vulgari eloquentia

- 1 2 3 Salvi, Sergio. Le lingue tagliate: storia delle minoranze linguistiche in Italia, Rizzoli, 1975, pp.195

- ↑ Domna, tant vos ai preiada (BdT 392.7), vv. 74-75

- ↑ Leopold Wagner, Max. La lingua sarda, a cura di Giulio Paulis – Ilisso, p. 78

- ↑ "Le sarde, une langue normale". Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ Dittamondo III XII 56 ss.

- ↑ روم أفارقة متبربرون ومتوحشون,

- ↑ Contu Giuseppe, Sardinia in Arabic sources, Annali della Facoltà di Lingue e Letterature Straniere dell'Università di Sassari, Vol. 3 (2003 pubbl. 2005), p. 287-297. ISSN 1828-5384, http://eprints.uniss.it/1055/

- ↑ "Archivio Cassinense Perg. Caps. XI, n. 11 " e "TOLA P., Codice Diplomatico della Sardegna, I, Sassari, 1984, p. 153"

- ↑ In nomine Domini amen. Ego iudice Mariano de Lacon fazo ista carta ad onore de omnes homines de Pisas pro xu toloneu ci mi pecterunt: e ego donolislu pro ca lis so ego amicu caru e itsos a mimi; ci nullu imperatore ci lu aet potestare istu locu de non (n)apat comiatu de leuarelis toloneu in placitu: de non occidere pisanu ingratis: e ccausa ipsoro ci lis aem leuare ingratis, de facerlis iustitia inperatore ci nce aet exere intu locu ...

- ↑ E inper(a)tor(e) ki l ati kastikari ista delegantzia e fagere kantu narat ista carta siat benedittu ...

- ↑ In nomine de Pater et Filiu et Sanctu Ispiritu. Ego iudigi Salusi de Lacunu cun muiere mea donna (Ad)elasia, uoluntate de Donnu Deu potestando parte de KKaralis, assolbu llu Arresmundu, priori de sanctu Saturru, a fagiri si carta in co bolit. Et ego Arresmundu, l(eba)nd(u) ass(o)ltura daba (su) donnu miu iudegi Salusi de Lacunu, ki mi illu castigit Donnu Deu balaus (a)nnus rt bonus et a issi et a (muiere) sua, fazzu mi carta pro kertu ki fegi cun isus de Maara pro su saltu ubi si ( ... )ari zizimi ( ... ) Maara, ki est de sanctu Saturru. Intrei in kertu cun isus de Maara ca mi machelaa(nt) in issu saltu miu (et canpa)niarunt si megu, c'auea cun istimonius bonus ki furunt armadus a iurari, pro cantu kertàà cun, ca fuit totu de sanctu Sat(ur)ru su saltu. Et derunt mi in issu canpaniu daa petra de mama et filia derectu a ssu runcu terra de Gosantini de Baniu et derectu a bruncu d'argillas e derectu a piskina d'arenas e leuat cabizali derectu a sa bia de carru de su mudeglu et clonpit a su cabizali de uentu dextru de ssa doméstia de donnigellu Cumitayet leuet tuduy su cabizali et essit a ssas zinnigas de moori de silba, lassandu a manca serriu et clonpit deretu a ssu pizariu de sellas, ubi posirus sa dìì su tremini et leuat sa bia maiori de genna (de sa) terra al(ba et) lebat su moori ( ... ) a sa terra de sanctu Saturru, lassandu lla issa a manca et lebat su moori lassandu a (manca) sas cortis d'oriinas de ( ... ) si. Et apirus cummentu in su campaniu, ki fegir(us), d'arari issus sas terras ipsoru ki sunt in su saltu miu et (ll)u castiari s(u) saltu et issus hominis mius de Sinnay arari sas terras mias et issas terras issoru ki sunt in saltu de ssus et issus castiari su saltu(u i)ssoru. Custu fegirus plagendu mi a mimi et a issus homi(nis) mius de Sinnay et de totu billa de Maara. Istimonius ki furunt a ssegari su saltu de pari (et) a poniri sus treminis, donnu Cumita de Lacun, ki fut curatori de Canpitanu, Cumita d'Orrù ( ... ) du, A. Sufreri et Iohanni de Serra, filiu de su curatori, Petru Soriga et Gosantini Toccu Mullina, M( ... ) gi Calcaniu de Pirri, C. de Solanas, C. Pullu de Dergei, Iorgi Cabra de Kerarius, Iorgi Sartoris, Laurenz( ... ) ius, G. Toccu de Kerarius et P. Marzu de Quartu iossu et prebiteru Albuki de Kibullas et P. de Zippari et M. Gregu, M. de Sogus de Palma et G. Corsu de sancta Ilia et A. Carena, G. Artea de Palma et Oliueri de Kkarda ( ... ) pisanu et issu gonpanioni. Et sunt istimonius de logu Arzzoccu de Maroniu et Gonnari de Laco(n) mancosu et Trogotori Dezzori de Dolia. Et est facta custa carta abendu si lla iudegi a manu sua sa curatoria de Canpitanu pro logu salbadori (et) ki ll'(aet) deuertere, apat anathema (daba) Pater et Filiu et Sanctu Ispiritu, daba XII Appostolos et IIII Euangelistas, XVI Prophetas, XXIV Seniores, CCC(XVIII) Sanctus Patris et sorti apat cun Iuda in ifernum inferiori. Siat et F. I. A. T.

- ↑ Ego Benedictus operaius de Santa Maria de Pisas Ki la fatho custa carta cum voluntate di Domino e de Santa Maria e de Santa Simplichi e de indice Barusone de Gallul e de sa muliere donna Elene de Laccu Reina appit kertu piscupu Bernardu de Kivita, cum Iovanne operariu e mecum e cum Previtero Monte Magno Kercate nocus pro Santa Maria de vignolas ... et pro sa doma de VillaAlba e de Gisalle cum omnia pertinentia is soro .... essende facta custa campania cun sii Piscupu a boluntate de pare torraremus su Piscupu sa domo de Gisalle pro omnia sua e de sos clericos suos, e issa domo de Villa Alba, pro precu Kindoli mandarun sos consolos, e nois demus illi duas ankillas, ki farmi cojuvatas, suna cun servo suo in loco de rnola, e sattera in templo cun servii de malu sennu: a suna naran Maria Trivillo, a sattera jorgia Furchille, suna fuit de sa domo de Villa Alba, e sattera fuit de Santu Petru de Surake ... Testes Judike Barusone, Episcopu Jovanni de Galtellì, e Prite Petru I upu e Gosantine Troppis e prite Marchu e prite Natale e prite Gosantino Gulpio e prite Gomita Gatta e prite Comita Prias e Gerardu de Conettu ... e atteros rneta testes. Anno dom.milles.centes.septuag.tertio

- ↑ Vois messer N. electu potestate assu regimentu dessa terra de Sassari daue su altu Cumone de Janna azes jurare a sancta dei evangelia, qui fina assu termen a bois ordinatu bene et lejalmente azes facher su offitiu potestaria in sa dicta terra de Sassari ...

- ↑ Francesco Cesare Casula, La storia di Sardegna, 1994

- ↑ Why is Catalan spoken in L'Alguer? – Corpus Oral de l'Alguerès

- ↑ Carlo Maxia, Studi Sardo-Corsi, Dialettologia e storia della lingua fra le due isole

- ↑ Ciurrata di la linga gadduresa, Atti del II Convegno Internazionale di Studi

- ↑ Incipit to "Lettera al Maestro" in "La Sardegna e la Corsica", Ines Loi Corvetto, Torino, UTET Libreria, 1993: Semper happisi desiggiu, Illustrissimu Segnore, de magnificare, & arrichire sa limba nostra Sarda; dessa matessi manera qui sa naturale insoro tottu sas naciones dessu mundu hant magnificadu & arrichidu; comente est de vider per isos curiosos de cuddas.

- 1 2 J. Arce, La literatura hispánica de Cerdeña. Revista de la Facultad de Filología, 1956

- ↑ ... L'Alguer castillo fuerte bien murado / con frutales por tierra muy divinos / y por la mar coral fino eltremado / es ciudad de mas de mil vezinos...

- ↑ Los diez libros de fortuna d'Amor (1573)

- ↑ Storia della lingua sarda, vol. 3, a cura di Giorgia Ingrassia e Eduardo Blasco Ferrer

- ↑ Juan Francisco Carmona Cagliari, 1610–1670, Alabança de San George obispu suelense: Citizen (in Spanish): “You, shepherd! What frightens you? Have you never seen some people gathering?”; Shepherd (in Sardinian): “Are you asking me if I'm married?”; Citizen (in Spanish): “You're not getting a grasp of what I say, do you? Oh, what an idiot shepherd!”; Shepherd (in Sardinian): “I'm actually thirsty and tired”; Citizen (in Spanish): “I'd better speak in Sardinian so that we understand each other better. (in Sardinian) Tell me, shepherd, where are you from?”; Shepherd: “I'm from Suelli, my lord, I’ve been ordered to bring my lord a present”; Citizen: “Ah, now you understand what I said, don't you!””. (“Ciudadano: Que tiens pastor, de que te espantas? que nunca has visto pueblo congregado?; Pastor: E ite mi nais, si seu coiadu?; Ciudadano: Que no me entiendes? o, que pastor bozal aqui me vino; Pastor: A fidi tengu sidi e istau fadiau; Ciudadano: Mejor sera que en sardo tambien able pues algo dello se y nos oigamos. Nada mi su pastori de undi seis?; Pastor: De Suedi mi Sennori e m’anti cumandadu portari unu presenti a monsignori; Ciudadano: Jmoi jà mi jntendeis su que apu nadu”).

- ↑ Jacinto Arnal de Bolea (1636), El Forastero, Antonio Galcerin editor, Cagliari - "....ofreciéndonos a la vista la insigne ciudad de Càller, corte que me dixeron era de aquel reino. ....La hermosura de las damas, el buen gusto de su alino, lo prendido y bien saconado de lo curioso-dandole vida con mil donaires-, la grandeza en los titulos, el lucimientos en los cavalleros, el concurso grande de la nobleza y el agasajo para un forastero no os los podrà zifrar mi conocimiento. Basta para su alavanza el deciros que alcuna vez, con olvido en mi peregrinaciò y con descuido en mis disdichas, discurria por los templos no estrano y por las calles no atajado, me hallava con evidencias grandes que era aquel sitio el alma de Madrid, que con tanta urbanidad y cortesìa se exercitavan en sus nobles correspondencias"

- ↑ Vicenç Bacallar, el sard botifler als orígens de la Real Academia Española - VilaWeb

- ↑ Rime diverse, Cagliari, 1595

- ↑ Jn Dei nomine Amen, noverint comente sende personalmente constituidos in presensia mia notariu et de sos testimongios infrascrittos sa viuda Caterina Casada et Coco mugere fuit de su Nigola Casada jàganu, Franziscu Casada et Joanne Casada Frades, filios de su dittu Nigola et Caterina Casada de sa presente cittade faguinde custas cosas gratis e de certa sciensia insoro, non per forza fraudu, malìssia nen ingannu nen pro nexuna attera sinistra macchinassione cun tottu su megius modu chi de derettu poden et deven, attesu et cunsideradu chi su dittu Nigola Casada esseret siguida dae algunos corpos chi li dein de notte, pro sa quale morte fettin querella et reclamo contra sa persona de Pedru Najtana, pro paura de sa justissia, si ausentait, in sa quale aussensia est dae unu annu pattinde multos dannos, dispesas, traballos e disusios.

- ↑ M. Lepori, Dalla Spagna ai Savoia. Ceti e corona della Sardegna del Settecento (Rome, 2003)

- ↑ Un arxipèlag invisible: la relació impossible de Sardenya i Còrsega sota nacionalismes, segles XVIII-XX – Marcel Farinelli, Universitat Pompeu Fabra. Institut Universitari d'Història Jaume Vicens i Vives, p. 285

- ↑ "Ichnussa – la biblioteca digitale della poesia sarda". Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "[ ...] Ciononostante le due opere dello Spano sono di straordinaria importanza, in quanto aprirono in Sardegna la discussione sul problema della lingua sarda, quella che sarebbe dovuta essere la lingua unificata ed unificante, che si sarebbe dovuta imporre in tutta l'isola sulle particolarità dei singoli dialetti e suddialetti, la lingua della nazione sarda, con la quale la Sardegna intendeva inserirsi tra le altre nazioni europee, quelle che nell'Ottocento avevano già raggiunto o stavano per raggiungere la loro attuazione politica e culturale, compresa la nazione italiana. E proprio sulla falsariga di quanto era stato teorizzato ed anche attuato a favore della nazione italiana, che nell'Ottocento stava per portare a termine il processo di unificazione linguistica, elevando il dialetto fiorentino e toscano al ruolo di "lingua nazionale", chiamandolo italiano illustre, anche in Sardegna l'auspicata lingua nazionale sarda fu denominata sardo illustre". Massimo Pittau, Grammatica del sardo illustre, Nuoro, pp. 11–12

- ↑ Saggio di grammatica sul dialetto sardo meridionale dedicato a sua altezza reale Maria Cristina di Bourbon infanta delle Sicilie duchessa del genevese, Cagliari, Reale stamperia, 1811

- ↑ Nou dizionariu universali sardu-italianu, Cagliari, Tipografia Arciobispali, 1832

- ↑ The phonology of Campidanian Sardinian : a unitary account of a self-organizing structure, Roberto Bolognesi, The Hague : Holland Academic Graphics

- ↑ S'italianu in Sardìnnia , Amos Cardia, Iskra

- ↑ "Limba Sarda 2.0S'italianu in Sardigna? Impostu a òbligu de lege cun Boginu – Limba Sarda 2.0". Limba Sarda 2.0. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "La limba proibita nella Sardegna del '700 da Ritorneremo, una storia tramandata oralmente". Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ King Charles Emmanuel III of Sardinia, Royal Note, 23 July 1760: "Since we must use for such teachings (lower schools), among the most cultured languages, the one that is the less distant from the native dialect and the most appropriate to public administration at the same time, we have decided to use Italian in the aforementioned schools, as it is in fact no more different from the Sardinian language than the Spanish one, and indeed the most educated Sardinians have already a grasp of it; it is also the most viable option to facilitate and increase trade; the Piedmontese in the Kingdom won't have to learn another language to be employed in the public sector, and the Sardinians could also find work on the continent." Original: "Dovendosi per tali insegnamenti (scuole inferiori) adoperare fra le lingue più colte quella che è meno lontana dal materno dialetto ed a un tempo la più corrispondente alle pubbliche convenienze, si è determinato di usare nelle scuole predette l'italiana, siccome quella appunto che non essendo più diversa dalla sarda di quello fosse la castigliana, poiché anzi la maggior parte dei sardi più colti già la possiede; resta altresì la più opportuna per maggiormente agevolare il commercio ed aumentare gli scambievoli comodi; ed i Piemontesi che verranno nel Regno, non avranno a studiare una nuova lingua per meglio abituarsi al servizio pubblico e dei sardi, i quali in tal modo potranno essere impiegati anche nel continente.

- ↑ Girolamo Sotgiu (1984), Storia della Sardegna Sabauda, Editori Laterza

- ↑ "Italian is as familiar to me as Latin, French or other foreign languages which one only partially learns through grammar study and the books, without fully getting the hang of them"[...] (Original: [...]"È tanto nativa per me la lingua italiana, come la latina, francese o altre forestiere che solo s’imparano in parte colla grammatica, uso e frequente lezione de’ libri, ma non si possiede appieno"[...]) said Andrea Manca Dell’Arca, agronomist from Sassari at the end of the 17th century (Ricordi di Santu Lussurgiu di Francesco Maria Porcu In Santu Lussurgiu dalle Origini alla "Grande Guerra" – Grafiche editoriali Solinas – Nuoro, 2005)

- ↑ "It would be a great innovation, with regard to both the civilizing process in Sardinia and the public education, to ban the Sardinian dialects in every social and ecclesiastical activity, mandating the use of the Italian language... It is also necessary to eradicate the Sardinian dialect [sic] and introduce Italian even for other good reasons; that is, to civilize that nation [referring to Sardinia], in order for it to comprehend the instructions and commands from the Government... (Carlo Baudi di Vesme, Political and economical considerations on Sardinia, 1848)" Original: "Una innovazione in materia di incivilimento della Sardegna e d’istruzione pubblica, che sotto vari aspetti sarebbe importantissima, si è quella di proibire severamente in ogni atto pubblico civile non meno che nelle funzioni ecclesiastiche, tranne le prediche, l’uso dei dialetti sardi, prescrivendo l’esclusivo impiego della lingua italiana… È necessario inoltre scemare l’uso del dialetto sardo ed introdurre quello della lingua italiana anche per altri non men forti motivi; ossia per incivilire alquanto quella nazione, sì affinché vi siano più universalmente comprese le istruzioni e gli ordini del Governo ... " (Carlo Baudi di Vesme, Considerazioni politiche ed economiche sulla Sardegna, 1848)

- ↑ Il primo inno d'Italia è sardo

- ↑ L. Marroccu, Il ventennio fascista

- ↑ M. Farinelli, The Invisible Motherland? The Catalan-Speaking Minority in Sardinia and Catalan Nationalism, p. 15

- ↑ "Quando a scuola si insegnava la lingua sarda". Il Manifesto Sardo.

- ↑ Lussu became Lusso, and Pilu changed to Pilo; a large number of Sardinian surnames were affected by this policy.

- ↑ Sardinia and the right to self-determination of peoples, Document to be presented to the European left University of Berlin – Enrico Lobina

- ↑ "Lingua sarda: dall’interramento alla resurrezione?". Il Manifesto Sardo. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ Lavinio, 1975, 2003

- ↑ "Dispersione scolastica, a Sassari e Cagliari il (triste) record italiano". Sardiniapost.it. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ New research shows strong support for Sardinian – Eurolang

- ↑ Educazione bilingue in Sardegna: problematiche generali ed esperienze di altri paesi, M.T.Pinna Catte, Sassari, 1992

- ↑ Oppo, Anna. Le lingue dei sardi, p. 50

- ↑ Norme in materia di tutela delle minoranze linguistiche storiche, Italian parliament

- ↑ "Il sardo è un dialetto. Campagna di boicottaggio contro l'editore Giunti". Sardiniapost.it. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "La lingua sarda a rischio estinzione – Disterraus sardus".

- ↑ ULS Planàrgia-Montiferru. "In sardu est prus bellu". Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ Il sardo non è una lingua ma un dialetto. Lo ha deciso la corte di Cassazione, L'Unione Sarda

- ↑ "I giudici della Cassazione: "Il sardo non è una vera lingua, è solamente un dialetto". aMpI: "gravissimo attacco alla lingua del popolo sardo"". Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ Giovanna Tonzanu, Sa limba sarda (article written in Italian)

- ↑ La lingua sarda oggi: bilinguismo, problemi di identità culturale e realtà scolastica, Maurizio Virdis (Università di Cagliari)

- ↑ The Sardinian professor fighting to save Gaelic – and all Europe's minority tongues, The Guardian

- ↑ A similar condition led Irish to be spoken only in certain areas, known as Gaeltacht (Edwards J., Language, society and identity, Oxford, 1985)

- ↑ "- Institut für Linguistik/Romanistik – Universität Stuttgart". Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "Una breve introduzione alla "Questione della lingua sarda" – Etnie". Etnie. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ Salminen, Tapani (1993–1999). "UNESCO Red Book on Endangered Languages: Europe:". Retrieved 2008-06-13.

- ↑ La Nuova Sardegna, 04/11/10, Per salvare i segni dell'identità – di Paolo Coretti

- ↑ Ai docenti di sardo lezioni in italiano, Sardegna 24 – Cultura

- ↑ Difendere l'italiano per resuscitare il sardo, Enrico Pitzianti, L'Indiscreto

- ↑ Roberto Bolognesi, Le identità linguistiche dei sardi, Cagliari, Condaghes, 2013

- ↑ Lingua e società in Sardegna – Mauro Maxia

- ↑ Marco Oggianu (2006-12-21). "Sardinien: Ferienparadies oder stiller Tod eines Volkes?". Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ Damien Simonis (2003). Sardinia. Lonely Planet Publications. pp. 240–241. ISBN 9781740590334.

- ↑ Sardaigne

- ↑ European Parliamentary Research Service. Regional and minority languages in the European Union, Briefing September 2016

- ↑ "404 Not Found-Regione Autonoma della Sardegna". Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "L’Ue richiama l’Italia: non ha ancora firmato la Carta di tutela – Cronaca – Messaggero Veneto". Messaggero Veneto. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "Università contro spending review "Viene discriminato il sardo"". SassariNotizie.com. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ redazione. "Il consiglio regionale si sveglia sulla tutela della lingua sarda". BuongiornoAlghero.it. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "Salviamo sardo e algherese in Parlamento". Alguer.it. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "Il sardo è un dialetto?". Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ Simone Tatti. "Do you speak... su Sardu?". focusardegna. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "Cagliari, promosso a pieni voti il tredicenne che ha dato l'esame in sardo – Sardiniapost.it". Sardiniapost.it. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- 1 2 "Eleonora d'Arborea in sardo? La prof. "continentale" dice no – Sardiniapost.it". Sardiniapost.it. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "Esame di maturità per la limba". la Nuova Sardegna. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "Quartu, esame di terza media in campidanese:studenti premiati in Comune". Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "Studentessa dialoga in sardo con il presidente dei docenti". la Nuova Sardegna. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ Antonio Maccioni. "In sardo all’esame di maturità. La scelta di Lia Obinu al liceo scientifico di Bosa". Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ Studente sostiene l'esame di terza media su Grazia Deledda interamente in sardo, L'Unione Sarda, 2016

- ↑ La maturità ad Orgosolo: studente-poeta in costume sardo, tesina in limba, Sardiniapost.it

- ↑ Col costume sardo all'esame di maturità discute la tesina in "limba", Casteddu Online

- ↑ "Sardinian 'rebels' redraw island map". Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ di Federico Spano. "La limba sulle mappe di Google". la Nuova Sardegna. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "Su Google Maps spariscono i nomi delle città in sardo". la Nuova Sardegna. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "Facebook in sardo: è possibile ottenerlo se noi tutti compiliamo la richiesta".

- ↑ "Come si mette la lingua sarda su Facebook". Giornalettismo.

- ↑ "Via alle traduzioni, Facebook in sardo sarà presto una realtà".

- ↑ Ora Facebook parla sardo, successo per la App in limba. Sardiniapost

- ↑ È arrivato Facebook in lingua sarda, Wired

- ↑ Telegram in sardu: oe si podet, Sa Gazeta

- ↑ Tecnologies de la sobirania, VilaWeb

- ↑ La limba nel cielo: le costellazioni ribattezzate in sardo, La Nuova Sardegna

- ↑ Storia della lingua sarda, vol. 3, a cura di Giorgia Ingrassia e Eduardo Blasco Ferrer, CUEC, pp. 227–230

- ↑ Stranos Elementos, musica per dare voce al disagio sociale

- ↑ Il passato che avanza a ritmo di rap – La Nuova Sardegna

- ↑ Cori e rappers in limba alla Biennale – La Nuova Sardegna

- ↑ La lingua sarda al cinema. Un’introduzione. Di Antioco Floris e Salvatore Pinna – UniCa

- ↑ Storia della lingua sarda, vol. 3, a cura di Giorgia Ingrassia e Eduardo Blasco Ferrer, CUEC, p. 226

- ↑ "Sardinia's parties strike deal to introduce Sardinian language teaching in schools". Nationalia. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "Proposta di legge n. 167 – XV Legislatura". Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "Lingua sarda, dalla Regione 3 milioni di euro per insegnarla nelle scuole". Sardegna Oggi. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ 30 e lode in lingua sarda per gli studenti tedeschi, La Donna Sarda

- ↑ "I tedeschi studiano il sardo nell’isola". la Nuova Sardegna. 18 May 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "Studenti cechi imparano il sardo – Cronaca – la Nuova Sardegna". la Nuova Sardegna. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "Ecco come insegno il sardo nella Repubblica Ceca". Sardiniapost.it. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "In città il professore giapponese che insegna la lingua sarda a Tokio". Archivio – La Nuova Sardegna. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "Limba made in Japan". Archivio – La Nuova Sardegna. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "Il professore giapponese che insegna il sardo ai sardi". Archivio – La Nuova Sardegna. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ Un docente giapponese in questione ha scritto il vocabolario sardo-italiano-giapponese, Vistanet.it

- ↑ Lingue di minoranza e scuola, Carta Generale. Ministero della Pubblica Istruzione

- ↑ Inchiesta ISTAT (2000), pg. 105–107

- ↑ "The internet as a Rescue Tool of Endangered Languages: Sardinian – Free University of Berlin" (PDF).

- ↑ IL VIDEO: Elisa, la studentessa cui è stata negata la tesina in sardo: "Semus in custa terra e no ischimus nudda" ("We live in this land and we don't know a thing about it")

- 1 2 Il ruolo della lingua sarda nelle scuole e nelle università sarde - Svenja Weisser, Universität Stuttgart, Institut für Linguistik/Romanistik

- ↑ "Caro Mastino, non negare l’evidenza: per te il sardo è una lingua morta. Che l’Università di Sassari vorrebbe insegnare come se fosse il latino". vitobiolchini. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "Lingua Sarda: La figuraccia di Mastino, rettore dell’Università di Sassari". Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ Language and nationalism in Europe, edited by Stephen Barbour and Cathie Carmichael, Oxford University Press, pp.178

- ↑ "- Institut für Linguistik/Romanistik – Universität Stuttgart". Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "No al sardo in Rai, Pigliaru: "Discriminazione inaccettabile"". la Nuova Sardegna. 1 August 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "Bill excluding Sardinian, Friulian from RAI broadcasts sparks protest". Nationalia. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "On Why I Translated Zakaria Tamer's Stories from Arabic into Sardinian – Arabic Literature (in English)". Arabic Literature (in English). Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "Niente messa in limba, lettera al vescovo: "Perché non parlare in sardo?"". Sardiniapost.it.

- ↑ "Messa vietata in sardo: lettera aperta all'arcivescovo Miglio". Casteddu Online.

- ↑ Sardinian, a digital language?, DLDP Sardinian Report, the Digital Language Diversity Project

- ↑ Lingua sarda: "trinta prenu" per i primi due studenti, Unica.it

- ↑ The Council of Europe Advisory Committee on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, Fourth Opinion on Italy, 2015

- ↑ Lingua sarda: il Consiglio d'Europa indaga lo stato italiano. Ne parliamo con Giuseppe Corongiu - SaNatzione

- ↑ Il Consiglio d'Europa: «Lingua sarda discriminata, norme non rispettate», L'Unione Sarda

- ↑ Resolution CM/ResCMN(2017)4 on the implementation of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities by Italy, Council of Europe

- ↑ et ipso quoque sermo Sardorum adhuc retinetnon pauca verba sermonis graeci atque ipse loquentium sonum graecisanum quendam prae se fert – Roderigo Hunno Baeza, Caralis Panegyricus, about 1516, manuscript preserved in the University Library of Cagliari

- 1 2 Le minoranze linguistiche in Italia

References

- Vincenzo Raimondo Porru, Saggio di gramatica sul dialetto sardo meridionale, Cagliari, 1811.

- Vincenzo Raimondo Porru, Nou Dizionariu Universali Sardu-Italianu. Cagliari, 1832

- Giovanni Spano, Ortografia Sarda Nazionale. Cagliari, Reale Stamperia, 1840.

- Giovanni Spano, Vocabolario Sardo-Italiano e Italiano-Sardo. Cagliari: 1851–1852.

- Max Leopold Wagner, Historische Lautlehre des Sardinischen, 1941.

- Max Leopold Wagner. La lingua sarda. Storia, spirito e forma. Berna: 1950.

- Max Leopold Wagner, Dizionario etimologico sardo, Heidelberg, 1960–1964.

- Michael Allan Jones, Sardinian Syntax, Routledge, 1993.

- Massimo Pittau, La lingua Sardiana o dei Protosardi, Cagliari, 1995

- B. S. Kamps and Antonio Lepori, Sardisch fur Mollis & Muslis, Steinhauser, Wuppertal, 1985.

- Shigeaki Sugeta, Su bocabolariu sinotticu nugoresu – giapponesu – italianu: sas 1500 paragulas fundamentales de sa limba sarda, Edizioni Della Torre, 2000

- Shigeaki Sugeta, Cento tratti distintivi del sardo tra le lingue romanze: una proposta, 2010.

- Salvatore Colomo, Vocabularieddu Sardu-Italianu / Italianu-Sardu.

- Luigi Farina, Vocabolario Nuorese-Italiano e Bocabolariu Sardu Nugoresu-Italianu.

- Michael Allan Jones, Sintassi della lingua sarda (Sardinian Syntax), Condaghes, Cagliari, 2003.

- Eduardo Blasco Ferrer, Linguistica sarda. Storia, metodi, problemi, Condaghes, Cagliari, 2003.

- Roberto Bolognesi and Wilbert Heeringa, Sardegna tra tante lingue: il contatto linguistico in Sardegna dal Medioevo a oggi, Condaghes, Cagliari, 2005.

- Roberto Bolognesi, Le identità linguistiche dei sardi, Condaghes

- Roberto Bolognesi, The phonology of Campidanian Sardinian : a unitary account of a self-organizing structure, The Hague : Holland Academic Graphics

- Amos Cardia, S'italianu in Sardìnnia, Iskra, 2006.

- Amos Cardia, Apedala dimòniu, I sardi, Cagliari, 2002.

- Francesco Casula, La Lingua sarda e l'insegnamento a scuola, Alfa, Quartu Sant'Elena, 2010.

- Antonio Lepori, Stòria lestra de sa literadura sarda. De su Nascimentu a su segundu Otuxentus, C.R., Quartu S. Elena, 2005.

- Antonio Lepori, Vocabolario moderno sardo-italiano: 8400 vocaboli, CUEC, Cagliari, 1980.

- Antonio Lepori, Zibaldone campidanese, Castello, Cagliari, 1983.

- Antonio Lepori, Fueddàriu campidanesu de sinònimus e contràrius, Castello, Cagliari, 1987.

- Antonio Lepori, Dizionario Italiano-Sardo Campidanese, Castello, Cagliari, 1988.

- Antonio Lepori, Gramàtiga sarda po is campidanesus, C.R., Quartu S. Elena, 2001.

- Francesco Mameli, Il logudorese e il gallurese, Soter, 1998.

- Alberto G. Areddu, Le origini "albanesi" della civiltà in Sardegna, Napoli 2007

- Gerhard Rohlfs, Le Gascon, Tübingen, 1935.

- Johannes Hubschmid, Sardische Studien, Bern, 1953.

- Giulio Paulis, I nomi di luogo della Sardegna, Sassari, 1987.

- Giulio Paulis, I nomi popolari delle piante in Sardegna, Sassari, 1992.

- Massimo Pittau, I nomi di paesi città regioni monti fiumi della Sardegna, Cagliari, 1997.

- Giuseppe Mercurio, S'allega baroniesa. La parlata sardo-baroniese, fonetica, morfologia, sintassi , Milano, 1997.

- H.J. Wolf, Toponomastica barbaricina, Nuoro, 1998.

- Eduardo Blasco Ferrer, Storia della lingua sarda, Cagliari, 2009.

- Eduardo Blasco Ferrer, Paleosardo. Le radici linguistiche della Sardegna neolitica, Berlin, 2010.

- Marcello Pili, Novelle lanuseine: poesie, storia, lingua, economia della Sardegna, La sfinge, Ariccia, 2004.

- Michelangelo Pira, Sardegna tra due lingue, Della Torre, Cagliari, 1984.

- Massimo Pittau, Grammatica del sardo-nuorese, Patron, Bologna, 1972.

- Massimo Pittau, Grammatica della lingua sarda, Delfino, Sassari, 1991.

- G. Mensching, 1992, Einführung in die sardische Sprache.

- Massimo Pittau, Dizionario della lingua sarda: fraseologico ed etimologico, Gasperini, Cagliari, 2000/2003.

- Antonino Rubattu, Dizionario universale della lingua di Sardegna, Edes, Sassari, 2003.

- Antonino Rubattu, Sardo, italiano, sassarese, gallurese, Edes, Sassari, 2003.

- Mauro Maxia, Lingua Limba Linga. Indagine sull’uso dei codici linguistici in tre comuni della Sardegna settentrionale, Cagliari, Condaghes 2006