Candida albicans

| Candida albicans | |

|---|---|

_cells.jpg) | |

| Dimorphic Candida albicans growing both as yeast cells and filamentous cells on YEPD agar | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Saccharomycetes |

| Order: | Saccharomycetales |

| Family: | Saccharomycetaceae |

| Genus: | Candida |

| Species: | C. albicans |

| Binomial name | |

| Candida albicans (C.P.Robin) Berkhout (1923) | |

| Synonyms | |

Candida albicans is a type of yeast that is commonly used as a model organism for biology. It is generally referred to as a dimorphic fungus since it grows both as yeast and filamentous cells. However it has several different morphological phenotypes.

It is a common member of human gut flora and does not seem to proliferate outside mammalian hosts.[4] It is detectable in the gastrointestinal tract and mouth in 40-60% of healthy adults.[5][6] It is usually a commensal organism, but can become pathogenic in immunocompromised individuals under a variety of conditions.[6][7] It is one of the few species of the Candida genus that cause the infection candidiasis in humans. Overgrowth of the fungus results in candidiasis (candidosis).[6][7] Candidiasis is for example often observed in HIV-infected patients.[8]

C. albicans is the most common fungal species isolated from biofilms either formed on (permanent) implanted medical devices or on human tissue.[9][10] C. albicans, together with C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis and C. glabrata, is responsible for 50–90% of all cases of candidiasis in humans.[7][11][12] A mortality rate of 40% has been reported for patients with systemic candidiasis due to C. albicans.[13] Estimates range from 2800 to 11200 deaths caused annually in the USA due to C. albicans causes candidiasis.[14]

C. albicans was for a long time considered an obligate diploid organism without a haploid stage. This is however not the case. Next to a haploid stage C. albicans can also exist in a tetraploid stage. The latter is formed when diploid C. albicans cells mate when they are in the opaque form.[15] The diploid genome size is approximately 29Mb, and up to 70% of the protein coding genes have not yet been characterized.[16] C. albicans is easily cultured in the lab and can be studied both in vivo as in vitro. Depending on the media different studies can be done as the media influences the morphological state of C. albicans. A special type of medium is CHROMagar™ Candida which can be used to identify different species of candida.[17][18]

Etymology

Candida albicans can be seen as a tautology. Candida comes from the Latin word candidus, meaning white. Albicans itself is the present participle of the Latin word albicō, meaning becoming white. This leads to white becoming white, making it a tautology.

It is often shortly referred to as thrush, candidiasis or candida. More than hundred synonyms have been used to describe C. albicans.[2][19] Over 200 species have been described within the candida genus. The oldest reference to thrush, most likely caused by C. albicans, dates back to 400 B.C. in Hippocrates' work Of the Epidemics describing oral candidiasis.[20][2]

Genome

The genome of C. albicans is almost 16Mb large, 8 chromosomes (28Mb for the diploid stage) and contains 6198 Open Reading Frames (ORFs). 70% of these ORFs have not yet been characterized. The whole genome has been sequenced making it one of the first fungi to be completely sequenced (next to Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe).[16][8] All open reading frames (ORFs) are also available in gateway adapted vectors. Next to this ORFeome there is also the availability of a GRACE (gene replacement and conditional expression) library to study essential genes in the genome of C. albicans.[21][22] The most commonly used strains to study C. albicans are the WO-1 and SC5314 strains. The WO-1 strain is known to switch between white-opaque form with higher frequency while the SC5314 strain is the strain used for gene sequence reference.[23]

One of the most important features of the C. albicans genome is the high heterozygosity. At the base of this heterozygosity lies the occurrence of numeric and structural chromosomal rearrangements and changes as means of generating genetic diversity by chromosome length polymorphisms (contraction/expansion of repeats), reciprocal translocations, chromosome deletions, Nonsynonymous single-base polymorphisms and trisomy of individual chromosomes. These karyotypic alterations lead to changes in the phenotype, which is an adaptation strategy of this fungus. These mechanisms are further being explored with the availability of the complete analysis of the C. albicans genome.[24][25][26]

An unusual feature of the Candida genus is that in many of its species (including C. albicans and C. tropicalis, but not, for instance, C. glabrata) the CUG codon, which normally specifies leucine, specifies serine in these species. This is an unusual example of a departure from the standard genetic code, and most such departures are in start codons or, for eukaryotes, mitochondrial genetic codes.[27][28][29] This alteration may, in some environments, help these Candida species by inducing a permanent stress response, a more generalized form of the heat shock response.[30] However this different codon usage makes it more difficult to study C. albicans protein-protein interactions in the model organism S. cerevisiae. To overcome this problem a C. albicans specific two-hybrid system was developed.[31]

The genome of C. albicans is highly dynamic, contributed by the different CUG translation, and this variability has been used advantageously for molecular epidemiological studies and population studies in this species. The genome sequence has allowed for identifying the presence of a parasexual cycle (no detected meiotic division) in C. albicans.[32] This study of the evolution of sexual reproduction in six Candida species found recent losses in components of the major meiotic crossover-formation pathway, but retention of a minor pathway.[32] The authors suggested that if Candida species undergo meiosis it is with reduced machinery, or different machinery, and indicated that unrecognized meiotic cycles may exist in many species. In another evolutionary study, introduction of partial CUG identity redefinition (from Candida species) into Saccharomyces cerevisiae clones caused a stress response that negatively affected sexual reproduction. This CUG identity redefinition, occurring in ancestors of Candida species, was thought to lock these species into a diploid or polyploid state with possible blockage of sexual reproduction.[33]

Morphology

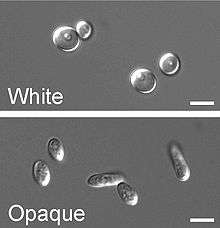

C. albicans exhibits a wide range of different morphological phenotypes due to phenotypic switching and bud to hypha transition. The yeast to hyphae transition is a rapid process and induced by environmental factors. Phenotypic switching is spontaneous, happens at lower rates and in certain strains up to seven different phenotypes are known. The best studied switching mechanism is the white to opaque switching (an epigenetic process). Other systems have been described as well. Two systems (the high frequency switching system and white to opaque switching) were discover by David R. Soll and colleagues.[34][35] Switching in C. albicans is often, but not always, influenced by environmental conditions such as the level of CO2, anaerobic conditions, medium used and temperature.[36]

Yeast to hyphae switching

Although often referred to as dimorphic, C. albicans is in fact polyphenic (often also referred to as pleomorphic).[37] When cultured in standard yeast laboratory medium, C. albicans grows as ovoid "yeast" cells. However, mild environmental changes in temperature, CO2, nutrients and pH can result in a morphological shift to filamentous growth.[38][39] Filamentous cells share many similarities with yeast cells. Both cell types seem to play a specific, distinctive role in the survival and pathogenicity of C. albicans. Yeast cells seem to be better suited for the dissemination in the bloodstream while hyphal cells have been proposed as a virulence factor. Hyphal cells are invasive and speculated to be important for tissue penetration, colonization of organs and surviving plus escaping macrophages.[40][41][42] The transition from yeast to hyphal cells is termed to be one of the key factors in the virulence of C. albicans, however it is not deemed necessary.[43] When C. albicans cells are grown in a medium that mimics the physiological environment of a human host, they grow as filamentous cells (both true hyphae and pseudohyphae). Candida albicans can also form Chlamydospores, the function of which remains unknown, but it is speculated they play a role in surviving harsh environments as they are most often formed under unfavorable conditions.[44]

The cAMP-PKA signaling cascade is crucial for the morphogenesis and an important transcriptional regulator for the switch from yeast like cells to filamentous cells is EFG1.[45][46]

High frequency switching

Besides the well studied yeast to hyphae transition other switching systems have been described.[47] One such system is the "high frequency switching" system. During this switching different cellular morphologies (phenotypes) are generated spontaneously. This type of switching does not occur en masse, represents a variability system and it happens independently from environmental conditions.[48] The strain 3153A produces at least seven different colony morphologies.[49][50][51] In many strains the different phases convert spontaneously to the other(s) at a low frequency. The switching is reversible, and colony type can be inherited from one generation to another. While several genes that are expressed differently in different colony morphologies have been identified, some recent efforts focus on what might control these changes. Further, whether a potential molecular link between dimorphism and phenotypic switching occurs is a tantalizing question.[52] Being able to switch through so many different (morphological) phenotypes makes C. albicans able to grow in different environments and this both as a commensal as a pathogen.[53]

In the 3153A strain, a gene called SIR2 (for silent information regulator), which seems to be important for phenotypic switching, has been found. SIR2 was originally found in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (brewer's yeast), where it is involved in chromosomal silencing—a form of transcriptional regulation, in which regions of the genome are reversibly inactivated by changes in chromatin structure (chromatin is the complex of DNA and proteins that make chromosomes). In yeast, genes involved in the control of mating type are found in these silent regions, and SIR2 represses their expression by maintaining a silent-competent chromatin structure in this region. The discovery of a C. albicans SIR2 implicated in phenotypic switching suggests it, too, has silent regions controlled by SIR2, in which the phenotype-specific genes may reside. How SIR2 itself is regulated in S. cerevisiae may yet provide more clues as to the switching mechanisms of C. albicans.

White to opaque switching

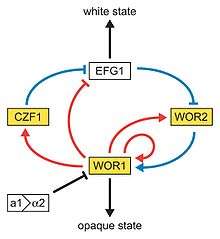

Next to the dimorphism and the first described high frequency switching system C. albicans undergoes another high frequency switching process called white to opaque switching, which is another phenotypic switching process in C. albicans. It was the second high-frequency switching system discovered in C. albicans.[54] The white to opaque switching is an epigenetic switching system.[55] Phenotypic switching is often used to refer to white-opaque switching, which consists of two phases: one that grows as round cells in smooth, white colonies (referred to as white form) and one that is rod-like and grows as flat, gray colonies (called opaque form). This switch from white cells to opaque cells is important for the virulence and the mating process of C. albicans as the opaque form is the mating competent form, being a million times more efficient in mating compared to the white type.[56][55][57] This switching between white and opaque form is regulated by the WOR1 regulator (White to Opaque Regulator 1) which is controlled by the mating type locus (MTL) repressor (a1-α2) that inhibits the expression of WOR1.[58] Besides the white and opaque phase there is also a third one: the gray phenotype. This phenotype shows the highest ability to cause cutaneous infections. The white, opaque and gray phenotypes form a tristable phenotypic switching system. Since it is often difficult to differentiate between white, opaque and gray cells phloxine B, a dye, can be added to the medium.[53]

A potential regulatory molecule in the white to opaque switching is Efg1p, a transcription factor found in the WO-1 strain that regulates dimorphism, and more recently has been suggested to help regulate phenotypic switching. Efg1p is expressed only in the white and not in the gray cell-type, and overexpression of Efg1p in the gray form causes a rapid conversion to the white form.[59][60]

White-GUT switch

A very special type of phenotypic switch is the white-GUT switch (Gastrointestinally-IndUced Transition). GUT cells are extremely adapted to survival in the digestive tract by metabolic adaptations to available nutrients in the digestive tract. The GUT cells live as commensal organisms and outcompete other phenotypes. The transition from white to GUT cells is driven by passage through the gut where environmental parameters trigger this transition by increasing the WOR1 expression.[61][62]

Role in disease

Candida is found worldwide but most commonly compromises immunocompromised individuals diagnosed with serious diseases such as HIV and cancer. Candida are ranked as one of the most common groups of organisms that cause nosocomial infections. Especially high risk individuals are patients that have recently undergone surgery, a transplant or are in the Intensive Care Units (ICU),[63] Candida albicans infections is the top source of fungal infections in critically ill or otherwise immuncompromised patients.[64] These patients predominantly develop oropharyngeal or thrush candidiasis, which can lead to malnutrition and interfere with the absorption of medication.[65] Methods of transmission include mother to infant through childbirth, people-to-people acquired infections that most commonly occur in hospital settings where immunocompromised patients acquire the yeast from healthcare workers and has a 40% incident rate. Men can become infected after having sex with a woman that has an existing vaginal yeast infection.[63] Parts of the body that are commonly infected include the skin, genitals, throat, mouth, and blood.[66] Distinguishing features of vaginal infection include discharge, and dry and red appearance of vaginal mucosa or skin. Candida continues to be the fourth most commonly isolated organism in bloodstream infections.[67]

Superficial and local infections

It commonly occurs, as a superficial infection, on mucous membranes in the mouth or vagina. Once in their life around 75% of women will suffer from vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) and about 90% of these infections are caused by C. albicans. It however may also affect a number of other regions. For example, higher prevalence of colonization of C. albicans was reported in young individuals with tongue piercing, in comparison to unpierced matched individuals.[68] To infect host tissue, the usual unicellular yeast-like form of C. albicans reacts to environmental cues and switches into an invasive, multicellular filamentous form, a phenomenon called dimorphism.[69] In addition, an overgrowth infection is considered superinfection, usually applied when an infection become opportunistic and very resistant to antifungals. It then becomes suppressed by antibiotics. The infection is prolonged when the original sensitive strain is replaced by the antibiotic-resistant strain.[70]

Candidiasis is known to cause GI symptoms particularly in immunocompromised patients or those receiving steroids (e.g. to treat asthma) or antibiotics. Recently, there is emerging literature that an overgrowth of fungus in the small intestine of non-immunocompromised subjects may cause unexplained GI symptoms. Small intestinal fungal overgrowth (SIFO) is characterized by the presence of excessive number of fungal organisms in the small intestine associated with gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. The most common symptoms observed in these patients were belching, bloating, indigestion, nausea, diarrhea, and gas. The underlying mechanism(s) that predisposes to SIFO is unclear. Further studies are needed; both to confirm these observations and to examine the clinical relevance of fungal overgrowth.[6][7][71]

Systemic infections

Systemic fungal infections (fungemias) including those by C. albicans have emerged as important causes of morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised patients (e.g., AIDS, cancer chemotherapy, organ or bone marrow transplantation). C. albicans often forms biofilms inside the body. Such C. albicans biofilms may form on the surface of implantable medical devices or organs. In these biofilms it is often found together with Staphylococcus aureus.[72][73][9][10] Such multispecies infections lead to higher mortalities.[74] In addition hospital-acquired infections by C. albicans have become a cause of major health concerns.[75][8] Especially once candida cells are introduced in the bloodstream a high mortality, up to 40-60% can occur.[8][76]

Although Candida albicans is the most common cause of candidemia, there has been a decrease in the incidence and an increases isolation of non-albicans species of Candida in recent years.[77] Preventive measures include keeping a healthy lifestyle including good nutrition, proper nutrition, and careful antibiotic use.

Economic implications

Given the fact that candidiasis is the fourth (to third) most frequent hospital acquired infection worldwide it leads to immense financial implications. Approximately 60000 cases of systemic candidiasis each year in the USA alone lead up to a cost to be between $2–4 billion.[78] The total costs for candidiasis are among the highest compared to other fungal infections due to the high prevalence.[79] The immense costs are partly explained by a longer stay in the intensive care unit or hospital in general. An extended stay for up to 21 more days compared to non infected patients is not uncommon.[80]

Proteins important for pathogenesis

Hwp1

Hwp1 stands for Hyphal wall protein 1. Hwp1 is a mannoprotein located on the surface of the hyphae in the hyphal form of Candida albicans. Hwp1 is a mammalian transglutaminase substrate. This host enzyme allows Candida albicans to attach stably to host epithelial cells.[81] Adhesion of Candida albicans to host cells is an essential first step in the infection process for colonization and subsequent induction of mucosal infection.

Slr1

RNA-binding protein Slr1 was recently discovered to play a role in instigating the hyphal formation and virulence in C. albicans.[82]

Candidalysin

Candidalysin is a cytolytic 31-amino acid α-helical peptide toxin that is released during hyphal formation. It contributes to virulence during mucosal infections.[83]

Genetic and genomic tools

Due to his nature as a model organism, being an important human pathogen and the alternative codon usage (CUG translated into serine rather than leucine), several specific projects and tools have been created to study C. albicans.[8]

Full sequence genome

The full genome of C. albicans has been sequenced and made publicly available in a candida database. The heterozygous diploid strain used for this full genome sequence project is the laboratory strain SC5314. The sequencing was done using a whole-genome shotgun approach.[84][85]

ORFeome project

Every predicted ORF has been created in a gateway adapted vector (pDONR207) and made publicly available. The vectors (plasmids) can be propagated in E.coli and grown on LB+gentamicin medium. This way every ORF is readily available in an easy to use vector. Using the gateway system it is possible to transfer the ORF of interest to any other gateway adapted vector for further studies of the specific ORF.[86][22]

CIp10 integrative plasmid

Contrary to the yeast S. cerevisiae episomal plasmids do not stay stable in C. albicans. In order to work with plasmids in C. albicans an integrative approach (plasmid integration into the genome) thus has to be used. A second problem is that most plasmid transformations are rather inefficient in C. albicans, however the CIp10 plasmid overcomes these problems and can be used with ease to transform C. albicans in a very efficient way. The plasmid integrates inside the RP10 locus as disruption of one RP10 allele does not seem to affect the viability and growth of C. albicans. Several adaptations of this plasmid have been made after the original became available.[87][88]

Candida two-hybrid (C2H) system

Due to the aberrant codon usage of C. albicans it is less feasible to use the common host organism (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) for two-hybrid studies. To overcome this problem a Candida albicans two-hybrid (C2H) system was created. The strain SN152 that is auxotrophic for leucine, arginine and histidine was used to create this C2H system. It was adapted by integrating a HIS1 reporter gene preceded by five LexAOp sequences. In the C2H system the bait plasmid (pC2HB) contains the staphylococcus aureus LexA BD, while the prey plasmid (pC2HP) harbors the viral AD VP16. Both plasmids are integrative plasmids since episomal plasmids do not stay stable in C. albicans. The reporter gene used in the system is the HIS1 gene. When proteins interact, the cells will be able to grow on medium lacking histidine due to the activation of the HIS1 reporter gene.[31][8]

Microarrays

Both DNA and protein microarrays were designed to study DNA expression profiles and antibody production in patients against C. albicans cell wall proteins.[89][90]

GRACE library

Using a tetracycline-regulatable promoter system a gene replacement and conditional expression (GRACE) library was created for 1152 genes. By using the regulatable promoter and having deleted 1 of the alleles of the specific gene it was possible to discriminate between non-essential and essential genes. Of the tested 1152 genes 567 showed to be essential. The knowledge on essential genes can be used to discover novel antifungals.[91]

Application in engineering

Candida albicans has been used in combination with carbon nanotubes (CNT) to produce stable electrically conductive bio-nano-composite tissue materials that have been used as temperature sensing elements[92]

Treatment

Treatment commonly includes:[93]

- amphotericin B, echinocandin, or fluconazole for systemic infections

- Nystatin for oral and esophageal infections

- Clotrimazole for skin and genital yeast infections[94]

Important to note is that similar to antibiotic resistance, resistance to many anti-fungals is becoming a big problem. New anti-fungals have to be developed to cope with this problem since only a limited number of anti-fungals are available.[95][96]

Notable C. albicans researchers

See also

- Intestinal permeability

- Torula yeast (Candida utilis)

- Neonatal infection

- codon usage

References

- ↑ Candida albicans at NCBI Taxonomy browser, url accessed 2006-12-26

- 1 2 3 The yeasts, a taxonomic study (4 ed.). 1998. ISBN 0444813128.

- ↑ McClary, Dan Otho (May 1952). "Factors Affecting the Morphology of Candida Albicans". Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 39 (2): 137–164. JSTOR 2394509. doi:10.2307/2394509.

- ↑ Odds, F.C. (1988). Candida and Candidosis: A Review and Bibliography (2nd ed.). London ; Philadelphia: Bailliere Tindall. ISBN 978-0702012655.

- ↑ Kerawala C, Newlands C, eds. (2010). Oral and maxillofacial surgery. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 446, 447. ISBN 978-0-19-920483-0.

- 1 2 3 4 Erdogan A, Rao SS (April 2015). "Small intestinal fungal overgrowth". Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 17 (4): 16. PMID 25786900. doi:10.1007/s11894-015-0436-2.

- 1 2 3 4 Martins N, Ferreira IC, Barros L, Silva S, Henriques M (June 2014). "Candidiasis: predisposing factors, prevention, diagnosis and alternative treatment". Mycopathologia. 177 (5–6): 223–240. PMID 24789109. doi:10.1007/s11046-014-9749-1.

Candida species and other microorganisms are involved in this complicated fungal infection, but Candida albicans continues to be the most prevalent. In the past two decades, it has been observed an abnormal overgrowth in the gastrointestinal, urinary and respiratory tracts, not only in immunocompromised patients, but also related to nosocomial infections and even in healthy individuals. There is a widely variety of causal factors that contribute to yeast infection which means that candidiasis is a good example of a multifactorial syndrome.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Calderone A, Clancy CJ, eds. (2012). Candida and Candidiasis (2nd ed.). ASM Press. ISBN 978-1-55581-539-4.

- 1 2 Kumamoto CA (2002). "Candida biofilms". Current Opinion in Microbiology. 5 (6): 608–11. PMID 12457706.

- 1 2 Donlan RM (2001). "Biofilm formation: a clinically relevant microbiological process". Clinical Infectious Diseases : an Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 33 (8): 1387–92. PMID 11565080. doi:10.1086/322972.

- ↑ Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ (January 2007). "Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: a persistent public health problem". Clin Microbiol Rev. 20 (1): 133–163. PMC 1797637

. PMID 17223626. doi:10.1128/CMR.00029-06.

. PMID 17223626. doi:10.1128/CMR.00029-06. - ↑ Schlecht, Lisa Marie; Freiberg, Jeffrey A.; Hänsch, Gertrud M.; Peters, Brian M.; Shirtliff, Mark E.; Krom, Bastiaan P.; Filler, Scott G.; Jabra-Rizk, Mary Ann (2015). "Systemic Staphylococcus aureus infection mediated by Candida albicans hyphal invasion of mucosal tissue". Microbiology. 161 (Pt 1): 168–81. PMC 4274785

. PMID 25332378. doi:10.1099/mic.0.083485-0.

. PMID 25332378. doi:10.1099/mic.0.083485-0. - ↑ Singh, Rachna; Chakrabarti, Arunaloke (2017). "Invasive Candidiasis in the Southeast-Asian Region". In Prasad, Rajendra. Candida albicans: Cellular and Molecular Biology (2 ed.). Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG. p. 27. ISBN 978-3-319-50408-7.

- ↑ Pfaller, M. A.; Diekema, D. J. (2007). "Epidemiology of Invasive Candidiasis: A Persistent Public Health Problem". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 20 (1): 133–63. PMC 1797637

. PMID 17223626. doi:10.1128/CMR.00029-06.

. PMID 17223626. doi:10.1128/CMR.00029-06. - ↑ Hickman MA, Zeng G, Forche A, Hirasawa MP, Abbey D, Harrison BD, Wang YM, Su CH, Bennett RJ, Wang Y, Berman J (2016). "The ‘obligate diploid’ Candida albicans forms mating-competent haploids". Nature. 494 (7435): 55–59. PMC 3583542

. doi:10.1038/nature11865.

. doi:10.1038/nature11865. - 1 2 http://www.candidagenome.org/cache/C_albicans_SC5314_genomeSnapshot.html

- ↑ "Development of Candida albicans Hyphae in Different Growth Media - Variations in Growth Rates, Cell Dimensions and Timing of Morphogenetic Events" (PDF) (132). 1986.

- ↑ Odds, F. C.; Bernaerts, R (1994). "CHROMagar Candida, a new differential isolation medium for presumptive identification of clinically important Candida species". Journal of clinical microbiology. 32 (8): 1923–9. PMC 263904

. PMID 7989544.

. PMID 7989544. - ↑ Simi, Vincent. "Origin of the Names of Species of Candida" (PDF).

- ↑ McCool, Logan. "The Discovery and Naming of Candida albicans" (PDF).

- ↑ Roemer T, Jiang B, Davison J, Ketela T, Veillette K, Breton A, Tandia F, Linteau A, Sillaots S, Marta C, Martel N, Veronneau S, Lemieux S, Kauffman S, Becker J, Storms R, Boone C, Bussey H (2003l). "Large-scale essential gene identification in Candida albicans and applications to antifungal drug discovery". Mol Microbiol. 38 (19): 167–81. PMID 14507372. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03697.x.

- 1 2 http://www.candidagenome.org/CommunityNews.shtml

- ↑ http://www.candidagenome.org/Strains.shtml#P37005

- ↑ Rustchenko-Bulgac, E. P. (1991). "Variations of Candida albicans Electrophoretic Karyotypes". J Bacteriol. 173 (173): 6586–6596. PMC 208996

.

. - ↑ Holmes, Ann R.; Tsao, Sarah; Ong, Soo-Wee; Lamping, Erwin; Niimi, Kyoko; Monk, Brian C.; Niimi, Masakazu; Kaneko, Aki; Holland, Barbara R.; Schmid, Jan; Cannon, Richard D. (2006). "Heterozygosity and functional allelic variation in the Candida albicans efflux pump genes CDR1 and CDR2". Molecular Microbiology. 62 (1): 170–86. PMID 16942600. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05357.x.

- ↑ Jones, T.; Federspiel, N. A.; Chibana, H.; Dungan, J.; Kalman, S.; Magee, B. B.; Newport, G.; Thorstenson, Y. R.; Agabian, N.; Magee, P. T.; Davis, R. W.; Scherer, S. (2004). "The diploid genome sequence of Candida albicans". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (19): 7329. doi:10.1073/pnas.0401648101.

- ↑ Ohama, T; Suzuki, Tsutomu; Mori, Miki; Osawa, Syozo; Ueda, Takuya; Watanabe, Kimitsuna; Nakase, Takashi (August 1993). "Non-universal decoding of the leucine codon CUG in several Candida species". Nucleic Acids Research. 21 (17): 1039–4045. PMC 309997

. PMID 8371978. doi:10.1093/nar/21.17.4039.

. PMID 8371978. doi:10.1093/nar/21.17.4039. - ↑ Arnaud, MB; Costanzo, MC; Inglis, DO; Skrzypek, MS; Binkley, J; Shah, P; Binkley, G; Miyasato, SR; Sherlock, G. "CGD Help: Non-standard Genetic Codes". Candida Genome Database. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ↑ Andrzej (Anjay) Elzanowski and Jim Ostell (7 July 2010). "The Alternative Yeast Nuclear Code". The Genetic Codes. Bethesda, Maryland, U.S.A.: National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ↑ Santos, MA; Cheesman, C; Costa, V; Moradas-Ferreira, P; Tuite, MF (February 1999). "Selective advantages created by codon ambiguity allowed for the evolution of an alternative genetic code in Candida spp.". Molecular Microbiology. 31 (3): 937–947. PMID 10048036. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01233.x.

- 1 2 Stynen, B; Van Dijck, P; Tournu, H (October 2010). "A CUG codon adapted two-hybrid system for the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans". Nucleic Acids Res. 38 (19): e184. PMC 2965261

. PMID 20719741. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq725.

. PMID 20719741. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq725. - 1 2 Butler G, Rasmussen MD, Lin MF, et al. (June 2009). "Evolution of pathogenicity and sexual reproduction in eight Candida genomes". Nature. 459 (7247): 657–62. PMC 2834264

. PMID 19465905. doi:10.1038/nature08064.

. PMID 19465905. doi:10.1038/nature08064. - ↑ Silva RM, Paredes JA, Moura GR, et al. (October 2007). "Critical roles for a genetic code alteration in the evolution of the genus Candida". EMBO J. 26 (21): 4555–65. PMC 2063480

. PMID 17932489. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7601876.

. PMID 17932489. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7601876. - ↑ ""White-opaque transition": a second high-frequency switching system in Candida albicans." (PDF). J Bacteriol. 1 (169): 189–197. 1987.

- ↑ Slutsky, B; Buffo, J; Soll, D. R. (1985). "High-frequency switching of colony morphology in Candida albicans". Science. 230 (4726): 666–9. PMID 3901258.

- ↑ "High-frequency switching in Candida albicans".

- ↑ Staniszewska, M; Bondaryk, M; Siennicka, K; Kurzatkowski, W (2012). "Ultrastructure of Candida albicans pleomorphic forms: phase-contrast microscopy, scanning and transmission electron microscopy". Polish journal of microbiology. 61 (61): 129–35. PMID 23163212.

- ↑ Si H, Hernday AD, Hirasawa MP, Johnson AD, Bennett RJ (2013). "Candida albicans White and Opaque Cells Undergo Distinct Programs of Filamentous Growth". PLoS Pathog. 9 (3): e1003210. PMC 3591317

. PMID 23505370. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003210.

. PMID 23505370. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003210. - ↑ Peter E. Sudbery (2011). "Growth of Candida albicans hyphae" (PDF). Nature Reviews Microbiology. 9 (10): 737–748. PMID 21844880. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2636. See figure 2.

- ↑ Sudbery, P; Gow, N; Berman, J (2004). "The distinct morphogenic states of Candida albicans". Trends in Microbiology. 12 (7): 317–24. PMID 15223059. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2004.05.008.

- ↑ Jiménez-López, Claudia; Lorenz, Michael C. (2013). "Fungal Immune Evasion in a Model Host–Pathogen Interaction: Candida albicans Versus Macrophages". PLoS Pathogens. 9 (11): e1003741. PMID 24278014. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003741.

- ↑ Berman J, Sudbery PE (2002). "Candida Albicans: a molecular revolution built on lessons from budding yeast". Nature Reviews Genetics. 3 (12): 918–930. PMID 12459722. doi:10.1038/nrg948.

- ↑ Shareck, J.; Belhumeur, P. (2011). "Modulation of Morphogenesis in Candida albicans by Various Small Molecules". Eukaryotic Cell. 10 (8): 1004. PMID 21642508. doi:10.1128/EC.05030-11.

- ↑ Staib P, Morschhäuser J (2007). "Chlamydospore formation in Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis--an enigmatic developmental programme.". Mycoses. 50 (1): 1–12. PMID 17302741. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0507.2006.01308.x.

- ↑ Sohn, K; Urban, C; Brunner, H; Rupp, S (2003). "EFG1 is a major regulator of cell wall dynamics in Candida albicans as revealed by DNA microarrays". Molecular microbiology. 47 (1): 89–102. PMID 12492856.

- ↑ Shapiro, R. S.; Robbins, N.; Cowen, L. E. (2011). "Regulatory Circuitry Governing Fungal Development, Drug Resistance, and Disease". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 75 (2): 213. PMID 21646428. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00045-10.

- ↑ Soll DR (2014). "The role of phenotypic switching in the basic biology and pathogenesis of Candida albicans". J Oral Microbiol. 6 (2): 895–9. PMC 3895265

. PMID 2828333. doi:10.3402/jom.v6.22993.

. PMID 2828333. doi:10.3402/jom.v6.22993. - ↑ Soll, D R (1 April 1992). "High-frequency switching in Candida albicans". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 5 (2): 183–203. ISSN 0893-8512. PMC 358234

. PMID 1576587.

. PMID 1576587. - ↑ Alby K, Bennett RJ (2009). "To switch or not to switch? Phenotypic switching is sensitive to multiple inputs in a pathogenic fungus" (PDF). Commun Integr Biol. 2 (6): 509–511. PMC 2710840

. PMID 19458191. doi:10.1091/mbc.E09-01-0040.

. PMID 19458191. doi:10.1091/mbc.E09-01-0040. - ↑ Slutsky, B; Buffo, J; Soll, D. R. (1985). "High-frequency switching of colony morphology in Candida albicans". Science. 230 (4726): 666–9. PMID 3901258.

- ↑ Vargas K, Wertz PW, Drake D, Morrow B, Soll DR (1994). "Differences in adhesion of Candida albicans 3153A cells exhibiting switch phenotypes to buccal epithelium and stratum corneum.". Infect Immun. 62 (4): 1328–1335. PMC 186281

.

. - ↑ Soll D.R. (2012). Signal Transduction Pathways Regulating Switching, Mating and Biofilm Formation in Candida Albicans and Related Species. In: G. Witzany (ed). Biocommunication of Fungi. Springer, 85-102. ISBN 978-94-007-4263-5.

- 1 2 Tao L, Du H, Guan G, Dai Y, Nobile C, Liang W, Cao C, Zhang Q, Zhong J, Huang G (2014). "Discovery of a "White-Gray-Opaque" Tristable Phenotypic Switching System in Candida albicans: Roles of Non-genetic Diversity in Host Adaptation". PLoS Biol. 12 (4): e1001830. PMC 3972085

. PMID 24691005. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001830.

. PMID 24691005. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001830. - ↑ ""White-opaque transition": a second high-frequency switching system in Candida albicans." (PDF). J Bacteriol. 1 (169): 189–197. 1987.

- 1 2 Rikkerrink E, Magee B, Magee P (1988). "Opaque-white phenotype transition: a programmed morphological transition in Candida albicans". J. Bact. 170 (2): 895–899. PMC 210739

. PMID 2828333.

. PMID 2828333. - ↑ Lohse MB, Johnson AD (2009). "White-opaque switching in Candida albicans". Curr Opin Microbiol. 12 (6): 650–654. PMC 2812476

. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2009.09.010.

. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2009.09.010. - ↑ Hnisz D, Tscherner M, Kuchler K (2011). "Opaque-white phenotype transition: a programmed morphological transition in Candida albicans". Methods Mol Biol. Methods in Molecular Biology. 734 (2): 303–315. ISBN 978-1-61779-085-0. PMID 21468996. doi:10.1007/978-1-61779-086-7_15.

- ↑ Morschhäuser J (2010). "Regulation of white-opaque switching in Candida albicans" (PDF). Med Microbiol Immunol.. 199 (3): 165–172. PMID 20390300. doi:10.1007/s00430-010-0147-0.

- ↑ Sonneborn A, Tebarth B, Ernst J (1999). "Control of white-opaque phenotypic switching in Candida albicans by the Efg1p morphogenetic regulator". Infection and Immunity. 67 (9): 4655–4660. PMC 96790

. PMID 10456912.

. PMID 10456912. - ↑ Srikantha T, Tsai L, Daniels K, Soll D (2000). "EFG1 Null Mutants of Candida albicans Switch but Cannot Express the Complete Phenotype of White-Phase Budding Cells". J. Bact. 182 (6): 1580–1591. PMC 94455

. PMID 10692363. doi:10.1128/JB.182.6.1580-1591.2000.

. PMID 10692363. doi:10.1128/JB.182.6.1580-1591.2000. - ↑ Pande, Kalyan; Chen, Changbin; Noble, Suzanne M (2013). "Passage through the mammalian gut triggers a phenotypic switch that promotes Candida albicans commensalism". Nature Genetics. 45 (9): 1088. PMID 23892606. doi:10.1038/ng.2710.

- ↑ Noble, Suzanne M.; Gianetti, Brittany A.; Witchley, Jessica N. (2016). "Candida albicans cell-type switching and functional plasticity in the mammalian host". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 15 (2): 96. PMID 27867199. doi:10.1038/nrmicro.2016.157.

- 1 2 Brosnahan, Mandy (July 22, 2013). "Candida Albicans". MicrobeWiki. Kenyon College.

- ↑ Sydnor, Emily (24 January 2011). "Hospital Epidemiology and Infection Control in Acute-Care Settings". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 24 (1): 141–173. PMC 3021207

. PMID 21233510. doi:10.1128/CMR.00027-10.

. PMID 21233510. doi:10.1128/CMR.00027-10. - ↑ Sardi, J. C. O. (2016-04-16). "Candida species: current epidemiology, pathogenicity, biofilm formation, natural antifungal products and new therapeutic options" (PDF). Journal of Medical Microbiology. 62 (Pt 1): 10–24. PMID 23180477. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.045054-0. Retrieved 2016-04-16.

- ↑ Tortora, Funke, Case. Microbiology, An Introduction 10th Edition. Pearson Benjamin Cummings. 2004,2007,2010

- ↑ Vazquez, Jose (2016-04-16). "Epidemiology, Management, and Prevention of Invasive Candidiasis". Medscape.org. Medscape. Retrieved 2016-04-16.

- ↑ Zadik Yehuda; Burnstein Saar; Derazne Estella; Sandler Vadim; Ianculovici Clariel; Halperin Tamar (March 2010). "Colonization of Candida: prevalence among tongue-pierced and non-pierced immunocompetent adults". Oral Dis. 16 (2): 172–5. PMID 19732353. doi:10.1111/j.1601-0825.2009.01618.x.

- ↑ Ryan KJ, Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- ↑ Tortora, Gerald, J. (2010). Microbiology: an Introduction. San Francisco, CA: Pearson Benjamin Cummings. p. 759.

- ↑ Mukherjee PK, Sendid B, Hoarau G, Colombel JF, Poulain D, Ghannoum MA (2015). "Mycobiota in gastrointestinal diseases". Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 12 (2): 77–87. PMID 25385227. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2014.188.

- ↑ Peters, Brian M.; Jabra-Rizk, Mary Ann; Scheper, Mark A.; Leid, Jeff G.; Costerton, John William; Shirtliff, Mark E. (2010). "Microbial interactions and differential protein expression in Staphylococcus aureus–Candida albicansdual-species biofilms". FEMS Immunology & Medical Microbiology. 59 (3): 493. doi:10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00710.x.

- ↑ Lin, Yi Jey; Alsad, Lina; Vogel, Fabio; Koppar, Shardul; Nevarez, Leslie; Auguste, Fabrice; Seymour, John; Syed, Aisha; Christoph, Kristina; Loomis, Joshua S. (2013). "Interactions between Candida albicans and Staphylococcus aureus within mixed species biofilms". Bios. 84: 30. doi:10.1893/0005-3155-84.1.30.

- ↑ Zago, Chaiene Evelin; Silva, Sónia; Sanitá, Paula Volpato; Barbugli, Paula Aboud; Dias, Carla Maria Improta; Lordello, Virgínia Barreto; Vergani, Carlos Eduardo (2015). "Dynamics of Biofilm Formation and the Interaction between Candida albicans and Methicillin-Susceptible (MSSA) and -Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)". PLOS ONE. 10 (4): e0123206. PMID 25875834. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0123206.

- ↑ Tortora, Gerald, J. (2010). Mibrobiology:an Introduction. San Francisco, CA: Pearson Benjamin Cummings. p. 758.

- ↑ Weinberger, M (2016-04-16). "Characteristics of candidaemia with Candida-albicans compared with non-albicans Candida species and predictors of mortality". J Hosp Infect. 61 (2): 146–54. PMID 16009456. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2005.02.009.

- ↑ Yapar, Nur (2016-04-16). "Epidemiology and risk factors for invasive candidiasis". Dovepress. 10: 95–105. PMC 3928396

. PMID 24611015. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S40160.

. PMID 24611015. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S40160. - ↑ Uppuluri, Priya; Khan, Afshin; Edwards, John E. (2017). "Current Trends in Candidiasis". In Prasad, Rajendra. Candida albicans: Cellular and Molecular Biology. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG. p. 6. ISBN 978-3-319-50408-7.

- ↑ Wilson, Leslie S.; Reyes, Carolina M.; Stolpman, Michelle; Speckman, Julie; Allen, Karoline; Beney, Johnny (2002). "The Direct Cost and Incidence of Systemic Fungal Infections". Value in Health. 5 (1): 26–34. PMID 11873380. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4733.2002.51108.x.

- ↑ Rentz, A. M.; Halpern, M. T.; Bowden, R (1998). "The impact of candidemia on length of hospital stay, outcome, and overall cost of illness". Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 27 (4): 781–8. PMID 9798034.

- ↑ Staab, J. F. (1999). "Adhesive and Mammalian Transglutaminase Substrate Properties of Candida albicans Hwp1". Science. 283 (5407): 1535–1538. ISSN 0036-8075. doi:10.1126/science.283.5407.1535.

- ↑ Ariyachet, C.; Solis, N. V.; Liu, Y.; Prasadarao, N. V.; Filler, S. G.; McBride, A. E. (2013). "SR-like RNA-binding protein Slr1 affects Candida albicans filamentation and virulence". Infection and Immunity. 81 (4): 1267–1276. ISSN 0019-9567. PMC 3639594

. PMID 23381995. doi:10.1128/IAI.00864-12.

. PMID 23381995. doi:10.1128/IAI.00864-12. - ↑ Duncan Wilson; Julian R. Naglik; Bernhard Hube (2016). "The Missing Link between Candida albicans Hyphal Morphogenesis and Host Cell Damage". PLoS Pathog. 12 (10): e1005867. PMC 5072684

. PMID 27764260. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1005867.

. PMID 27764260. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1005867. - ↑ Van Het Hoog, Marco; Rast, Timothy J; Martchenko, Mikhail; Grindle, Suzanne; Dignard, Daniel; Hogues, Hervé; Cuomo, Christine; Berriman, Matthew; Scherer, Stewart; Magee, BB; Whiteway, Malcolm; Chibana, Hiroji; Nantel, André; Magee, PT (2007). "Assembly of the Candida albicans genome into sixteen supercontigs aligned on the eight chromosomes". Genome Biology. 8 (4): R52. PMID 17419877. doi:10.1186/gb-2007-8-4-r52.

- ↑ Van Het Hoog, Marco; Rast, Timothy J; Martchenko, Mikhail; Grindle, Suzanne; Dignard, Daniel; Hogues, Hervé; Cuomo, Christine; Berriman, Matthew; Scherer, Stewart; Magee, BB; Whiteway, Malcolm; Chibana, Hiroji; Nantel, André; Magee, PT (2007). "Assembly of the Candida albicans genome into sixteen supercontigs aligned on the eight chromosomes". Genome Biology. 8 (4): R52. PMID 17419877. doi:10.1186/gb-2007-8-4-r52.

- ↑ Cabral, Vitor; Chauvel, Murielle; Firon, Arnaud; Legrand, Mélanie; Nesseir, Audrey; Bachellier-Bassi, Sophie; Chaudhari, Yogesh; Munro, Carol A.; d'Enfert, Christophe (2012). "Host-Fungus Interactions". Methods in Molecular Biology. 845: 227. ISBN 978-1-61779-538-1. doi:10.1007/978-1-61779-539-8_15.

|chapter=ignored (help) - ↑ Chauvel, Murielle; Nesseir, Audrey; Cabral, Vitor; Znaidi, Sadri; Goyard, Sophie; Bachellier-Bassi, Sophie; Firon, Arnaud; Legrand, Mélanie; Diogo, Dorothée; Naulleau, Claire; Rossignol, Tristan; d'Enfert, Christophe (2012). "A Versatile Overexpression Strategy in the Pathogenic Yeast Candida albicans: Identification of Regulators of Morphogenesis and Fitness". PLOS ONE. 7 (9): e45912. PMID 23049891. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045912.

- ↑ Walker, Louise A.; MacCallum, Donna M.; Bertram, Gwyneth; Gow, Neil A.R.; Odds, Frank C.; Brown, Alistair J.P. (2009). "Genome-wide analysis of Candida albicans gene expression patterns during infection of the mammalian kidney". Fungal Genetics and Biology. 46 (2): 210. PMID 19032986. doi:10.1016/j.fgb.2008.10.012.

- ↑ Mochon, A. Brian; Ye, Jin; Kayala, Matthew A.; Wingard, John R.; Clancy, Cornelius J.; Nguyen, M. Hong; Felgner, Philip; Baldi, Pierre; Liu, Haoping (2010). "Serological Profiling of a Candida albicans Protein Microarray Reveals Permanent Host-Pathogen Interplay and Stage-Specific Responses during Candidemia". PLoS Pathogens. 6 (3): e1000827. PMID 20361054. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000827.

- ↑ Walker, Louise A.; MacCallum, Donna M.; Bertram, Gwyneth; Gow, Neil A.R.; Odds, Frank C.; Brown, Alistair J.P. (2009). "Genome-wide analysis of Candida albicans gene expression patterns during infection of the mammalian kidney". Fungal Genetics and Biology. 46 (2): 210. PMID 19032986. doi:10.1016/j.fgb.2008.10.012.

- ↑ Roemer, Terry; Jiang, Bo; Davison, John; Ketela, Troy; Veillette, Karynn; Breton, Anouk; Tandia, Fatou; Linteau, Annie; Sillaots, Susan; Marta, Catarina; Martel, Nick; Veronneau, Steeve; Lemieux, Sebastien; Kauffman, Sarah; Becker, Jeff; Storms, Reginald; Boone, Charles; Bussey, Howard (2003). "Large-scale essential gene identification in Candida albicans and applications to antifungal drug discovery". Molecular Microbiology. 50 (1): 167–81. PMID 14507372. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03697.x.

- ↑ Di Giacomo, Raffaele; Maresca, Bruno; Porta, Amalia; Sabatino, Paolo; Carapella, Giovanni; Neitzert, Heinz-Christoph (2013). "Candida albicans/MWCNTs: A Stable Conductive Bio-Nanocomposite and Its Temperature-Sensing Properties". IEEE Transactions on Nanotechnology. 12 (2): 111–114. doi:10.1109/TNANO.2013.2239308.

- ↑ Rambach, G; Oberhauser, H; Speth, C; Lass-Flörl, C (2011). "Susceptibility of Candida species and various moulds to antimycotic drugs: Use of epidemiological cutoff values according to EUCAST and CLSI in an 8-year survey". Medical mycology : official publication of the International Society for Human and Animal Mycology. 49 (8): 856–63. PMID 21619497. doi:10.3109/13693786.2011.583943 (inactive 2017-05-17).

- ↑ Tortora. Microbiology an Introduction (10th ed.). San Francisco, CA.: Pearson Benjamin Cummings. p. 759.

- ↑ https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/antifungal-resistance.html

- ↑ Sellama A, Whiteway M (2016). "Recent advances on Candida albicans biology and virulence". F1000Res. 5: 7. doi:10.12688/f1000research.9617.1.

Further reading

- Waldman A, Gilhar A, Duek L, Berdicevsky I (May 2001). "Incidence of Candida in psoriasis—a study on the fungal flora of psoriatic patients". Mycoses. 44 (3–4): 77–81. PMID 11413927. doi:10.1046/j.1439-0507.2001.00608.x.

- Zordan RE, Miller MG, Galgoczy DJ, Tuch BB, Johnson AD (October 2007). "Interlocking Transcriptional Feedback Loops Control White-Opaque Switching in Candida albicans". PLoS Biology. 5 (10): e256. PMC 1976629

. PMID 17880264. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050256.

. PMID 17880264. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050256. - Rossignol T, Lechat P, Cuomo C, Zeng Q, Moszer I, d'Enfert C (January 2008). "CandidaDB: a multi-genome database for Candida species and related Saccharomycotina". Nucleic Acids Research. 36 (Database issue): D557–61. PMC 2238939

. PMID 18039716. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm1010.

. PMID 18039716. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm1010. - "How Candida albicans switches phenotype – and back again: the SIR2 silencing gene has a say in Candida's colony type". NCBI Coffeebreak. 1999-11-24. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Candida albicans. |

- Candida Genome Database

- U.S. National Institutes of Health on the Candida albicans genome

- Mycobank data on Candida albicans

- Labs working on Candida