Canada–France relations

| |

Canada |

France |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic Mission | |

| Embassy of Canada, Paris | Embassy of France, Ottawa |

Modern Canadian–French relations have been marked by high levels of military and economic cooperation, but also by periods of diplomatic discord, primarily over the status of Quebec.

According to a 2014 BBC World Service Poll, 64% of Canadians view France's influence positively, with 20% expressing a negative view, while 87% of French people view Canadian influence positively, with 6% expressing a negative view.[1]

History

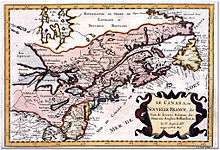

European colonization

In 1720 the British controlled Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Northern and a big part of Western Canada but otherwise nearly all of Eastern Canada, from the Labrador shore and on the Atlantic coast to the Great Lakes and beyond, was under French domination. While the gradual conquest of New France by the British, culminating in Wolfe's victory at the Plains of Abraham in 1759, deprived France of her North American empire, the 'French of Canada' – Québécois or habitants, Acadians, Métis, and others – remained

After the British conquest, French immigration to Canada continued on a small scale until the start of the wars between France and Britain, 1792–1815. During this time French books circulated widely, and the French Revolution led many conservative refugees to seek asylum in Canada. The Anglophone population of Canada also grew rapidly after the American Revolution. Francophone opinion among the rural habitants towards France turned negative after 1793. As English subjects, the habitants, led by their conservative priest and landowners, rejected the revolution's impiety, regicide, and anti-Catholic persecution. The habitants supported Britain in the War of 1812 against the United States.[2] Many Canadians also speak French from their settlement in Canada in, 1534

Dominion of Canada

Early in Canada's history foreign affairs were under the control of the British Government. Canada pushed against these legal barriers to further its interests. Alexander Galt, Canada's informal representative in London, in 1878, attempted to conclude a commercial treaty with France. He failed because tariff preference for France violated British policy. The Foreign Office in London was unsupportive of sovereign diplomacy by Canada, and France was moving to new duties on foreign shipping and her embarkation and a general policy of protection. Galt's efforts did set the stage for a successful treaty in 1893 negotiated by Sir Charles Tupper (1821-1915), Canada's High Commissioner in London. However, that treaty was signed by the British ambassador to France.[3]

In 1882, the province of Quebec dispatched its own representative to Paris, Hector Fabre. The federal government responded by asking him to become Canada's agent-general in France. He and his successor Philippe Roy represented both levels of government informally until 1912, when the Tory government asked Roy to resign from the Quebec position because of fears of a possible conflict-of-interest.[4]

World Wars

A realignment of the great powers made allies of Canada (as member of the British Empire) and France just in time for the two World Wars that would dominate the first half of the 20th century.

The Canadian Expeditionary Force spent much of the First World War on French soil, helping France to repel the German invasion; and it was in France, at Vimy Ridge, where one of the most famous battles in Canadian history took place.

In December 1917 the accidental explosion of the French freighter Mont Blanc, carrying five million pounds of explosives, devastated Halifax, Nova Scotia, killing 2,000 and injuring 9,000. The SS Mont-Blanc had been chartered by the French government to carry munitions to Europe; France was not blamed and charges against its captain were dropped.[5]

Second World War

In the Second World War Canada and France were initially allies against Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. After the Fall of France in 1940 most Western governments broke off relations with the Vichy regime, however Canada continued to have relations with Vichy until 1942.[4]

Canada had planned a military invasion of the islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon. Controlled until the end of 1941 by Vichy France, it was the liberation by the Free French under Admiral Muselier that put an end to any invasion projects by Canada.

Eventually, Canada became an important ally and staunch supporter of General Charles de Gaulle's Free French Forces. De Gaulle himself re-entered France following the Normandy invasion via the Canadian-won Juno Beach, and during a lavish state visit to Ottawa in 1944, departed the assembled crowd with an impassioned call of "Vive le Canada! Vive la France!"

Suez Crisis

During the Suez Crisis the Canadian government was concerned with what might be a growing rift between western allied nations. Lester B. Pearson, who would later become the Prime Minister of Canada, went to the United Nations and suggested creating a United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) in the Suez to "keep the borders at peace while a political settlement is being worked out." Both France and Britain rejected the idea, so Canada turned to the United States. After several days of tense diplomacy, the United Nations accepted the suggestion, and a neutral force not involving the major alliances (NATO and the Warsaw Pact—though Canadian troops participated since Canada spearheaded the idea of a neutral force) was sent with the consent of Nasser, stabilizing conditions in the area.[6][7] The Suez Crisis also contributed to the adoption of a new Canadian national flag without references to that country's past as a colony of France and Britain. De Gaulle's visit to French-speaking Quebec in 1967 was heavily influenced by lingering tensions from a decade earlier.

Tensions over the status of Quebec

In July 1967, while on an official state visit to Canada, President de Gaulle ignited a storm of controversy when he exclaimed, before a crowd of 100,000 in Montreal, "Vive le Québec Libre!" (Long live free Quebec!). Coming as it did in the centennial year of Canadian Confederation, and amid the backdrop of Quebec's Quiet Revolution, such a provocative statement on the part of a widely respected statesman and liberator of France had a wide-ranging effect not only on Franco-Canadian relations but on relations between Quebec and the rest of Canada as well.

De Gaulle, a proponent of national sovereignty, proposed on several subsequent occasions what he termed the "Austro-Hungarian solution" for Canada (based on the dual-monarchic union shared between Austria and Hungary from 1867 to 1918), which appeared similar to the "sovereignty association" model later championed by René Lévesque.

While some historians have speculated that France under de Gaulle went so far as to set up a spy network in Canada and even give aid to Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) terrorists in the years leading up to 1967, France's intervention in Canadian intergovernmental relations remained largely in the realm of diplomatic rhetoric. Indeed, as Quebec, under the reformist Liberal government of Jean Lesage, was turning away from a more isolationist past and attempting to find for itself a new place within the Canadian federation and the wider francophone world, a willing and enthusiastic de Gaulle was eager to give aid to Quebec's newfound nationalist ambitions.

Master Agreement

The first step towards Quebec developing an "international personality" distinct from that of Canada, viewed by many as a stepping stone towards full independence, was for Quebec to develop relations with other "nations" independent from those of Canada. This effort began in earnest following de Gaulle's return to power, when France and Quebec began regularly exchanging ministers and government officials. Premier Lesage, for example, visited de Gaulle three times between 1961 and 1965.

Lesage's statement to the Quebec National Assembly that the French Canadian identity, culture, and language were endangered by a "cultural invasion from the USA," which threatened to make Canada a "cultural satellite of the United States" mirrored exactly the Gaullists concern for France's cultural survival in the face on an English onslaught. In this light, France and Quebec set about in the early 1960s negotiating exchange agreements in the areas of education, culture, technical cooperation, and youth exchange. The federal government of Lester B. Pearson, which had just appointed a Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism and was taking other steps to ensure the place of French within Canada, would not stand for a province usurping a federal power (foreign policy), and so signed a Master Agreement with France in 1965 that allowed for provinces to cooperate directly with France, but only in areas of exclusive provincial jurisdiction (such as education). It was not envisioned at the time by the federal government how much this agreement, and the doors it opened, would come to haunt them in the coming years.

The "Quebec Mafia"

The significant contingent of Quebec sovereignty supporters within the French government and the upper levels of the French foreign and civil services (primarily, but not exclusively, Gaullists), who came to be known as the "Quebec Mafia" within the Canadian foreign service and the press, took full advantage of the Master Agreement of 1965 to further their vision for Canada. While such instances were numerous, two are of particular notoriety:

Direct relations with Quebec

Shortly after de Gaulle's 1967 Montreal address, the French Consulate General in Quebec City, already viewed by many as a de facto embassy, was enlarged and the office of Consul General at Quebec replaced, by de Gaulle's order, with that of Consul General to the Quebec Government. At the same time, the flow of officials to Quebec City increased further, and it became accepted practice for high officials to visit Quebec without going to Ottawa at all – despite Ottawa's repeated complaints about the breaches of diplomatic protocol.

Many of these French officials, notably French Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Jean de Lipkowski, greatly angered and embarrassed the Canadian government by vocally supporting Quebec independence while in Canada. The media spoke of a "Quebec Mafia" in Paris.[8]

La Francophonie

One issue that sparked tensions between France and Canada began shortly after the creation of la Francophonie, an international organization of wholly and partially French-speaking countries modeled somewhat after the Commonwealth of Nations. While Canada agreed in principle to the organization's creation, it was dismayed by France's position that not only should Quebec participate as an equal, independent member, but that the federal government and (by omission) the other provinces with significant French minorities could not. This was seen by many French-Canadians outside of Quebec as a betrayal. This was also seen by some Canadians as France supporting the Quebec sovereignty movement. Some go as far as saying the Francophonie was created to help push the international recognition of Quebec, but in reality the Francophonie was created to promote international cooperation between all French speaking nations, including many newly independent former French colonies in Africa.

The first salvo in the Francophonie affair was launched in the winter of 1968 when Gabon, under pressure from France, invited Quebec – and not Canada or the other provinces – to attend a February francophone education conference in Libreville. Despite protests from the federal government the Quebec delegation attended and was treated to full state honours. In retaliation, Prime Minister Pearson took the extraordinary step of officially breaking off relations with Gabon. Pierre Trudeau, then Justice Minister, accused France of "using countries which have recently become independent for her own purposes" and threatened to break diplomatic relations with France.

The next such educational conference, held in 1969 in Congo (Kinshasa), would end in a relative win for the Canadian government. Congo (Kinshasa), which was a former colony of Belgium, was not as susceptible to French pressure as Gabon. At first it sent an invitation only to the federal government, which happily contacted the provinces concerned (Quebec, New Brunswick, Ontario, and Manitoba) about organizing a single delegation. Quebec, dismayed over the lack on an invitation, complained to the French, who then put pressure on Zaire, which then issued a second belated invitation to Quebec – offering as justification Quebec's attendance at the Gabon conference. Despite the last-minute offer, Canada and the provinces had already reached an agreement whereby the provinces would attend as sub-delegations of the main Canadian delegation.

The final rounds in the effort to include Canada (and not Quebec separately) in la Francophonie would take place in the months leading up the organizations founding conference in Niger in 1969. It was this conference that would set the precedent that would be followed to this day, and so neither France, Quebec, or Canada were prepared to go home the loser. For its part, France demanded that Quebec – and only Quebec – be issued an invitation. Niger – influenced in no small part by a promise of four years of "special" educational aid, a grant of 20,000 tons of wheat, and a geological survey of Niger offered by Canadian special envoy Paul Joseph James Martin the month before – issued Canada the sole invitation and asked that the federal government bring with it representatives of the interested provinces. The invitation, however, left open the prospect of Quebec being issued a separate invitation if the federal government and the provinces could not come to an agreement.

Much to the consternation of the French and the indépendantistes within the Quebec government, Ottawa and the provinces reached an agreement similar to the arrangement employed in Zaire – with a federal representative leading a single delegation composed of delegates from the interested provinces. Under this arrangement la Francophonie would grow to become a major instrument of Canadian foreign aid on par with the Commonwealth, although clearly less important politically.

Normalized relations

De Gaulle's resignation in 1969, and more importantly the 1970 election of the Liberals in Quebec under Robert Bourassa gave impetus to the calls on both sides for normalization of France-Canada relations. While the ultra-Gaullists and the remaining members of the 'Quebec Mafia' continue to occasionally cause headaches for Canada - such as a 1997 initiative by 'Mafia' members to have the French Post Office issue a stamp commemorating de Gaulle's 1967 visit to Montreal - never again would relations reach anything close to the hostility of the late 1960s.

The Gaullist policy of 'dualism' towards Canada, which called for distinct and separate relations between France and Canada and France and Quebec, has been replaced with a purposely ambiguous policy of ni-ni standing for ni ingérance, ni indifférence (no interference, but no indifference). While the French government continues to maintain cultural and diplomatic ties with Quebec, it is generally careful to treat the Canadian federal government with a great deal of respect.

In 2012 French president François Hollande explained this ni-ni policy states "the neutrality of France while ensuring France will accompany Québec in its destinies."[9]

Saint Pierre and Miquelon boundary dispute

The maritime boundary between the tiny French islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon (off the coast of Newfoundland) and Canada has long been a simmering point of contention between the two countries. As each country expanded its claimed territorial limit in the second half of the twentieth century, first to 12 nautical miles (22 km), then to 200 nautical miles (370 km), these claims began to overlap and a maritime boundary needed to be established.

While the countries agreed to a moratorium on undersea drilling in 1967, increased speculation about the existence of large oil deposits combined with the need to diversify economies after the regional cod fishery collapse triggered a new round of negotiations.

In 1989, Canada and France put the boundary question to an international court of arbitration. In 1992, the court awarded France a 24 nmi (44 km) exclusive economic zone surrounding the islands, as well as a 200 nmi (370 km) long, 10.5 nmi (19.4 km) wide corridor to international waters (an area totaling 3,607 sq nmi (12,370 km2). This fell significantly short of France's claims, and the resulting reduction in fish quotas created a great deal of resentment among the islands fishermen until a joint management agreement was reached in 1994.

Former CSE agent, Fred Stock, revealed in the Ottawa Citizen (May 22, 1999) that Canada had used the surveillance system known as ECHELON to spy on the French Government over the boundary issue.

The application of UNCLOS and article 76 (Law of the Sea) will extend the exclusive economic zone of states using complex calculations. France is likely to claim a section of the Continental Shelf south of the corridor granted by the 1992 decision and a new dispute may arise between France and Canada.

Sarkozy, Harper, Charest, and trade policy

In the 2007 and 2008, French President Nicolas Sarkozy,[10] Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper, and Quebec Premier Jean Charest[11] all spoke in favour of a Canada–EU free trade agreement. In October 2008, Sarkozy became the first French President to address the National Assembly of Quebec. In his speech he spoke out against Quebec separatism, but recognized Quebec as a nation within Canada. He said that, to France, Canada was a friend, and Quebec was family.[10]

Trade

Trade between the two countries is relatively modest when compared to trade with their immediate continental neighbours, but still significant. France was in 2010 Canada's 11th largest destination for exports and its fourth largest in Europe.[12]

Additionally, Canada and France are important to each other as entry points to their respective continental free markets (North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the European Union). Moreover, the Montreal-Paris air route is one of the most flown routes between Europe and a non-European destination.

While Canada and France often find themselves on the opposite sides of such trade disputes as agricultural free trade and the sale of genetically modified food, they co-operate closely on such issues as the insulation of cultural industries from free trade agreements (something both countries are strongly in favour of).

In 2006 France was the seventh ranked destination of Canadian exports (0.7%), and ninth ranked source of imports to Canada (1.3%).[13]

Other ties

Academic and intellectual

France is the 5th largest source country for foreign students to Canada (1st among European source countries). According to 2003–2004 figures from UNESCO, France is also the 4th most popular destination for Canadian post-secondary students, and the most popular non-English-speaking destination. For French post-secondary students, Canada is their 5th most popular destination; it ranks 2nd in terms of non-European destinations.[14]

Haglund and Massie (2010) argue that French Canadian intellectuals after 1800 developed the theme that Quebec had been abandoned and ignored by France. By the 1970s, however, there was a reconsideration based on Quebec's need for French support.[15] The Association Française d'Etudes Canadiennes was formed in 1976 to facilitate international scholarly communication, especially among geographers such as Pierre George, the first president, 1976–86.[16]

Resident diplomatic missions

- Canada has an embassy in Paris.[17] Quebec also maintains a paradiplomatic Government Office called Délégation générale du Québec à Paris.[18]

- France has an embassy in Ottawa and consulates-general in Moncton, Montreal, Quebec City, Toronto and Vancouver.[19]

See also

Bibliography

- Bosher, John Francis. The Gaullist attack on Canada 1967-1997. Montreal : McGill-Queen's University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-7735-1808-8.

- Haglund, David G. and Justin Massie. "L'Abandon de l'abandon: The Emergence of a Transatlantic 'Francosphere' in Québec and Canada's Strategic Culture," Quebec Studies (Spring/Summer2010), Issue 49, pp 59–85

In French

- Bastien, Frédéric. Relations particulières : la France face au Québec après de Gaulle. Montreal : Boréal, 1999. ISBN 2-89052-976-2.

- Galarneau, Claude. La France devant l'opinion canadienne, 1760-1815 (Quebec: Presses de l'Université Laval, 1970)

- Joyal, Serge, and Paul-André Linteau, eds. France-Canada-Québec. 400 ans de relations d'exception (2008)

- Pichette, Robert. Napoléon III, l'Acadie et le Canada français. Moncton NB : Éditions d'Acadie, 1998. ISBN 2-7600-0361-2.

- Savard, Pierre. Entre France rêvée et France vécue. Douze regards sur les relations franco-canadiennes aux XIXe et XXe siècles (2009)

- Thomson, Dale C. De Gaulle et le Québec. Saint Laurent QC: Éditions du Trécarré, 1990. ISBN 2-89249-315-3.

Notes and references

- ↑ 2013 World Service Poll BBC

- ↑ Claude Galarneau, La France devant l'opinion canadienne, 1760–1815 (Quebec: Presses de l'Université Laval, 1970)

- ↑ Robert A. M. Shields, "The Canadian Treaty Negotiations With France: A Study In Imperial Relations 1878-83," Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research (1967) 40#102 pp 186-202

- 1 2 "Page Not Found / Page introuvable". Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ Alan Ruffman, The Halifax Explosion: Realities and Myths (1992)

- ↑ "Message to the Congress Transmitting the 11th Annual Report on United States Participation in the United Nations". University of California Santa Barbara. January 14, 1958. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ↑ "Suez crisis, 1956". The Arab-Israeli conflict, 1947-present. August 28, 2001. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ↑ Bosher (2000). The Gaullist Attack on Canada, 1967-1997. McGill-Queens. pp. chapter 6.

- ↑ "Québec: Hollande 'pour la continuité'". Le Figaro. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- 1 2 "Sarkozy professes love for Quebec and Canada". Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑

- ↑ "Canada's State of Trade: Trade and Investment Update 2011". Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ Canada Is A Trading Nation - Canada's Major Trading Partners Archived June 3, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Foreign Affairs Canada – Relations Canada – France

- ↑ David G. Haglund and Justin Massie. "L'Abandon de l'abandon: The Emergence of a Transatlantic 'Francosphere' in Québec and Canada's Strategic Culture," Quebec Studies (Spring/Summer2010), Issue 49, pp 59–85

- ↑ Jean-Pierre Augustin, "Pierre George et l'Association Française d'Etudes Canadiennes (AFEC): 1976–2006," Cahiers de Géographie du Québec (Sept 2008) 52#146 pp 335–336.

- ↑ "Government of Canada - Gouvernement du Canada". Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ "Voici le Québec - Délégation générale du Québec à Paris". Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ "La France au Canada". Retrieved 27 April 2016.