Campbell v MGN Ltd

| Campbell v Mirror Group Newspapers Ltd | |

|---|---|

| |

| Court | House of Lords |

| Transcript(s) | Full text of judgment |

| Court membership | |

| Judge(s) sitting | Lord Nicholls, Lord Hoffman, Baroness Hale, Lord Carswell, Lord Hope |

Campbell v Mirror Group Newspapers Ltd [2004] UKHL 22 was a House of Lords decision regarding human rights and privacy in English law.

Facts

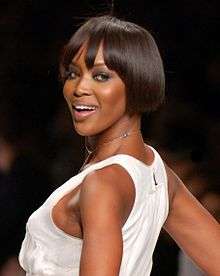

Well-known model Naomi Campbell was photographed leaving a rehabilitation clinic, following public denials that she was a recovering drug addict. The photographs were published in a publication run by MGN.

Campbell sought damages under the English law through her lawyers Schillings who engaged Richard Spearman QC to bring a claim for breach of confidence engaging section 6 of the Human Rights Act, which required the court to operate compatibly with the European Convention on Human Rights. The desired result was a ruling that the English tort action for breach of confidence, subject to the ECHR provisions upholding the right to private and family life, would require the court to recognize the private nature of the information, and hold that there was a breach of her privacy.

Rather than challenge the disclosure of the fact she had been a drug addict, she challenged the disclosure of information about the location of her Narcotics Anonymous meetings. The photographs, she argued, formed part of this information.

Judgment

First instance

MGN was found liable. MGN appealed.

Court of Appeal

MGN was not liable; the photographs could be published since, apparently, they were peripheral to the published story and served only to show her in a better light. It was within journalists' margin of appreciation to decide whether such "peripheral" information should be included.

Campbell appealed on the basis, inter alia, that the aforementioned breach of confidence, subject to human rights principles of privacy, had occurred.

House of Lords

The House of Lords held by a majority (Lords Nicholls and Hoffmann dissenting), that MGN was liable. Baroness Hale, Lord Hope, Lord Carswell held that the picture added something of 'real significance'. The court engaged in a balancing test. Firstly determining whether the applicant had a reasonable expectation of privacy (thus determining whether Art.8 ECHR was involved), it then asked if the claimant was successful would this result in a significant inference with freedom of expression (balancing Art. 8 with Art. 10). It was held that Campbell's right to privacy (ECHR, Sch 1, Part I, Art 8) outweighed MGN's right to freedom of expression (ECHR Art 10).

Lord Hoffmann and Lord Nicholls dissented on the ground that as the Mirror was allowed to publish the fact that she was a drug addict and that she was receiving treatment for her addiction that printing the pictures of her leaving her NA meeting was within the margin of appreciation of the editors as they were allowed to state that she was an addict and receiving treatment for her addiction. Lord Nicholls observed that "confidence" was an artificial term for what could more naturally be termed "privacy".

Lord Hope of Craighead noted that a duty of confidence arises wherever the defendant knows, or ought to know, that the claimant can reasonably expect their privacy to be protected, approving A v B plc,[1] . Where there is doubt, the test of what is "highly offensive to a reasonable person"[2] in the plaintiff's position[3] can be used for guidance.

Baroness Hale said the following.

| “ | The basic principles

132. Neither party to this appeal has challenged the basic principles which have emerged from the Court of Appeal in the wake of the Human Rights Act 1998. The 1998 Act does not create any new cause of action between private persons. But if there is a relevant cause of action applicable, the court as a public authority must act compatibly with both parties' Convention rights. In a case such as this, the relevant vehicle will usually be the action for breach of confidence, as Lord Woolf CJ held in A v B plc [2002] EWCA Civ 337, [2003] QB 195, 202, para 4: "[Articles 8 and 10] have provided new parameters within which the court will decide, in an action for breach of confidence, whether a person is entitled to have his privacy protected by the court or whether the restriction of freedom of expression which such protection involves cannot be justified. The court's approach to the issues which the applications raise has been modified because, under section 6 of the 1998 Act, the court, as a public authority, is required not to 'act in a way which is incompatible with a Convention right'. The court is able to achieve this by absorbing the rights which articles 8 and 10 protect into the long-established action for breach of confidence. This involves giving a new strength and breadth to the action so that it accommodates the requirements of these articles." |

” |

See also

- English tort law

- Douglas v Hello! Ltd [2005] EWCA Civ 595

- His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales v Associated Newspapers Ltd [2006] EWCA Civ 1776

- Privacy in English law