Campana reliefs

Campana reliefs (also Campana tiles) are Ancient Roman terracotta reliefs made from the middle of the first century BC until the first half of the second century AD. They are named after the Italian collector Giampietro Campana, who first published these reliefs (1842).

The reliefs were used as friezes at the top of a wall below the roof, and in other exterior locations, such as ridge tiles and antefixes, but also as decoration of interiors, typically with a number of sections forming a horizontal frieze. They were produced in unknown quantities of copies from moulds and served as decoration for temples as well as public and private buildings, as cheaper imitations of carved stone friezes. They originated in the terracotta tiled roofs of the Etruscan temples. A wide variety of motifs from mythology and religion featured on the reliefs as well as images of everyday Roman life, landscapes and ornamental themes. Originally they were painted in colour, of which only traces of this occasionally remain. They were mainly produced in the region of Latium around the city of Rome, and their use was also largely limited to this area. Five distinct types were produced. Today examples are found in almost all major museums of Roman art worldwide.

History of research

With intensified excavation in the Mediterranean in the nineteenth century, terracotta reliefs increasingly came to light in and around Rome, from which original architectural contexts were determined. Metal and marble objects had previously been the most sought by excavators, scholars and collectors, but at this time artefacts in other materials received wider interest, beginning with the late-18th century appreciation of Greek vases which when they first appeared were thought to represent Etruscan pottery.

The first collector to make the tiles items of interest was marchese Giampietro Campana. His influence and contemporary reputation in archaeology was so great that he was named an honorary member of the Instituto di corrispondenza archeologica. He published his collection in 1842 in Antiche opere in plastica ("Ancient works in plastic arts"), in which his findings on the reliefs were first laid out in a scholarly fashion. Thus the tiles became known as Campana reliefs. Afterwards Campana was sentenced to imprisonment for embezzlement: in 1858 he lost his honorary membership in the Istituto di corrispondenza archeologica and his collection was pawned and sold. The terracotta reliefs owned by him are now in the Louvre in Paris, the British Museum in London and the Hermitage in St Petersburg.

Other collectors, such as August Kestner, also collected the reliefs and fragments of them in greater numbers. Today examples are found in most larger collections of Roman archaeological finds, though the majority of the reliefs are in Italian museums and collections.

Despite Campana's research, for a long time the reliefs were rather neglected. They were viewed as handicrafts, thus inherently inferior, and not art, like marble sculptures. The idea that they should be treated as important sources for the craftwork of the period, for decorative fashions, and for their iconography only achieved prominence in the early years of the twentieth century. In 1911 Hermann von Rohden and Hermann Winnefeld published Architektonische Römische Tonreliefs der Kaiserzeit ("Roman Architectural Clay Reliefs of the Imperial Period") with a volume of images in Reinhard Kekulé von Stradonitz's series Die antiken Terrakotten. This was the first attempt to organise and classify the reliefs according to the emerging principles of Art history. The two authors first distinguished the main types, discussed their use and considered their development, style, and iconography. The book remains fundamental. Thereafter, apart from the publication of new finds, interest flagged for more than fifty years. In 1968 Adolf Heinrich Borbein's thesis Campanareliefs. Typologische und Stilkritische Untersuchungen ("Campana Reliefs: Typological and Stylistic Investigations") brought these archaeological finds to wider attention. In his work, Borbein was able to establish the development of the Campana reliefs from their origins among Etruscan-Italiote terracotta tiles. He also dealt with the use of motifs and templates derived from other media and pointed out that the artisans thereby produced creative new works.

Since Borbein's publication, researchers have mainly devoted themselves to chronological aspects or the preparation of catalogues of material from recent excavations and publications of old collections. In 1999 Marion Rauch produced an iconographic study Bacchische Themen und Nilbilder auf Campanareliefs ("Bacchic Themes and Nile Images in Campana Reliefs") and in 2006 Kristine Bøggild Johannsen described the usage contexts of the tiles in Roman villas on the basis of recent archaeological finds. She showed that the reliefs were among the most common decorations of Roman villas from the middle of the first century BC until the beginning of the second century AD, both in the country houses of the nobility and in the essentially agricultural villae rusticae.[1]

Material, technique, production, and painting

The quality of the ceramic product depended principally on the quality and processing of the clay. Particular importance attached to the tempering, when the clay (of uniform consistency) had various additives mixed in: sand, chopped straw, crushed brick, or even volcanic pozzolan. These additives minimised the contraction of the tile as it dried so that it retained its shape and did not develop cracks. These additives can be recognised as little red, brown, or black flecks, especially noticeable when crushed brick is used. Through the investigation of closed collections in the archaeological collection of Heidelberg University[2] and the Museum August Kestner in Hannover[3] gradations in the fineness of the structure were determined.

The tiles were not individually made as unique artworks but as series. From an original relief (the punch) a mould in the shape of a negative was produced. Then the moist clay was pressed into these moulds. Probably the image and the framing decoration were formed separately, since framing decoration is seen which has been applied to various designs. After they had dried, the tiles were removed from the mould and possibly lightly reworked. Then they were fired. After firing and cooling, the terracotta was painted,[4] though sometimes the paint was applied before firing. Usually the reliefs received a coating, which acted as a surface for painting. This could be white paint or grey-yellow paint in Augustan times but it could also be stucco.

At present, no canonical, presecribed use of colours can be detected, except that at least from Augustan times the background was usually in light blue regardless of the scenes and motifs, but it could include two or more other colours as well. The colour of human skin was usually in something between dark red and hot pink. In Dionysiac scenes, skin could also be painted a reddy-brown. In Augustan times light yellow was not unusual for skin. At Hannover, violet-brown, reddy brown, purple, red, yellow, yellow-brown, turquoise-green, dark bown, pink, blue, black, and white can all be identified.[5] Today the paint is lost in almost all cases and only residual traces can be recognised.

Distribution and dating

Nearly all Campana reliefs are from Central Italy, especially Latium. The largest and most important workshops seem to have been in Latium, especially in the neighbourhood of the city of Rome. Outside Latium the tiles are found mostly in Campania and in the former Etruscan sphere. At the end of the 1990s Marion Rauch compiled the reliefs with Dionysiac-Bacchic themes and was able to confirm this range for the motifs she was investigating. Nile scenes[6] are found only in Latium. No pieces have been found in the Greek areas of southern Italy or in Sicily.[7] An example from the Akademisches Kunstmuseum in Bonn, showing a Nike killing a bull was allegedly found in Agia Triada in Greece.[8] Some stuccoed examples derive from the western part of the Roman empire, the ancient regions of Hispania and Gaul (modern Spain and France).[9]

The earliest Campana reliefs were made in the middle of the first century BC, during the final period of the Roman Republic, and they were most common in the first quarter of the first century AD. At this time, the reliefs experienced not only their greatest extent but also their greatest variety of motifs. The final reliefs derive from about two hundred years later - production and use stopped in the time of Hadrian. While this general dating is largely viewed as secure, the exact date of the individual pieces can rarely be given. A relative chronology might be determined on the basis of comparison of motifs and styles. Iconographic research is unhelpful for this purpose because the motifs derive from a traditional repertoire, which was used largely without variation over a long period of time. Motifs from daily life are more helpful, however, since some of them depict datable building work such as the Capitoline Temple, which was built in AD 82 and is depicted on a relief from the Louvre Museum,[10] providing a terminus ante quem for that tile.

A better aid to dating is the quality of the clay. Over time their consistency became coarser, looser, more granular, and also lighter. The ornamental trimmings of the tiles are also useful: because they were the same for whole series of motifs, so one can reconstruct their relationships in the workshops and suggest contemporaneity. Very common motifs like the Ionian cymatium and palmettes are of only limited use, because these were used by a wide variety of workshops, even at the same time. Finally, sixe comparisons can also help with dating. Moulds were not only made from the original punch, but also often from tiles themselves. This leads to a natural "shrinkage" of the new tiles' dimensions. Because the moulds were sometimes reused for long periods of time, there are sometimes noticeable changes in the size of the tiles. For the motif depicting the Curetes performing a weapon dance around the baby Zeus, the moulds can be traced over a period of 170 years. In the process, the tiles lost about 40% of their size as a result of the repeated reuse of completed tiles as moulds. Therefore, in tiles which share a motif, the smaller can be identified as the younger. The motif also lost clarity through repeated remoulding.

Types and use

Even when it is known exactly where a relief tile was found, there is no absolute certainty because to this day no tiles have been found in the place of their original use. Scholars largely agree that the tiles served decorative and practical functions, although it is uncertain exactly which part of the building they were placed on.[11] Their origin in Etruscan-Italiote temple architecture is clear and certain, but it can nevertheless be assumed that temples were not the primary usage context at least in the tiles' later phases. On account of their consistently modest scale, the reliefs were more suitable for close viewing, which implies use on smaller buildings. Whereas their Etruscan and Italiote precursors served to cover wooden temple roofs and protect them from weathering, the Campana reliefs seem to have been used far more in secular contexts. There they lost their protective functions and became wall decorations. For a time both forms of use were found side by side on temples, until finally the Campana reliefs lost their older use. On account of their fragility, the bricks must have been replaced often - it is suggested that this would have occurred once every twenty-five years or so. At first they were replaced with copies of the previous decorative tiles, but later newer motifs were substituted also. Increasingly from the first century stone temples replaced earlier buildings in wood, and Campana reliefs were only used in restorations.[12]

Campana reliefs can be arranged on five bases: chronology, geography, iconography, shape and use.[13] The most productive system is classification based on the shape of the tile. The categories used are cladding tiles, ridge tiles, sima tiles, crowning tiles and antefixes.

- Cladding tiles: On the upper border, where the tile forms a smooth edge, there was decoration with an egg and dart pattern and the lower border is decorated with Lotus, palmettes, and anthemia. The lower edge follows the contour of the decorative pattern. There were three or four holes in each tile, through which tiles were tied to the wall.[14]

- Sima and Crowning tiles belong together. They were connected by use of the Tongue and groove method. On top of the sima was a tongue which was inserted into the underside of the crowning tile. The sima joined the cladding tile with an egg and dart pattern, a smooth strip was left on the underside. Waterspouts could be incorporated into the sima. The crowning tiles usually feature ornamental, floral patterns. They were equipped with slots on the underside, into which the sima was inserted. Together, the two tile types found use as the eaves of the roof.[15]

- Ridge tiles' were decorated with the same reliefs as the cladding tiles. They were finished on the upper side by a palmette and anthemion pattern and shared their shape, but lacked holes. On the lower side they were equipped with slots like the crowning tiles. These tiles were intended for interior decoration, where they could form longer friezes.[16]

- Antefixes sat on or above the eaves, the lowest row of tiles and closed off the front opening. They were composed of two parts. The curved tile was placed over the bricks of the eave, while the front portion closed the roof cavity off with a vertical tile. These tiles can be decorated and were often painted.[17]

These terracotta tiles had parallels in their development with the marble decorative reliefs of the "neo-Attic form" of the Late Republic and Early Empire, though their dissimilar shapes were not necessarily mutually dependent. Both had their own unique types and themes. In production and presentation, the marble reliefs were single works, while the Campana reliefs were made in series and once place in a united frieze did not operate as a single work.[18]

Motifs

The Campana reliefs show great diversity in their motifs. However, the images can be grouped into four large categories:

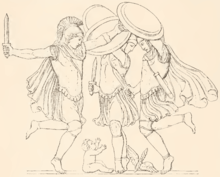

- Mythological themes: in turn divisible into three categories. Firstly, the Homeric epics with the Trojan War and the events which followed (such as the Odyssey. Secondly, the deeds of heroes, especially Heracles, but also Theseus and others. Thirdly, Dionysiac themes.

- Landscapes, especially scenes of the Nile

- Daily life: depictions of day-to-day Roman life as well as less frequent events like Triumphs. They include depictions of the theatre, the palaestra, the circus and even prisoners.

- Ornamental images including not just completely ornamental designs, such as vines, but also masks and gorgon heads.

The Egyptian elements in many tiles are of particular interest, such as the cladding tiles held in the British Museum[19] and in the Museum August Kestner in Hannover, which include crude imitations of Egyptian hieroglyphs - rarely encountered in Roman art.[20] They are also of great interest for study of ancient buildings and art, such as the aforementioned Capitoline temple.[21]

Bibliography

- Hermann von Rohden, Hermann Winnefeld. Architektonische Römische Tonreliefs der Kaiserzeit. Verlag W. Spemann, Berlin und Stuttgart 1911 Digitalisation of the text and of the plates Further digitalisation

- Adolf Heinrich Borbein. Campanareliefs. Typologische und stilkritische Untersuchungen. Kerle, Heidelberg 1968 (Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts. Römische Abteilung, Ergänzungsheft 14)

- Rita Perry. Die Campanareliefs. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-1827-8 (Katalog der Sammlung Antiker Kleinkunst des Archäologischen Instituts der Universität Heidelberg, Band 4)

- Marion Rauch. Bacchische Themen und Nilbilder auf Campanareliefs. Leidorf, Rahnden 1999; ISBN 3-89646-324-1 (Internationale Archäologie, Band 52)

- Anne Viola Siebert. Geschichte(n) in Ton. Römische Architekturterrakotten. Schnell + Steiner, Regensburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-7954-2579-1 (Museum Kestnerianum 16)

Notes

- ↑ On the history of scholarship on the Campana reliefs, see: Anne Viola Siebert: Geschichte(n) in Ton. Römische Architekturterrakotten. Schnell + Steiner, Regensburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-7954-2579-1 (Museum Kestnerianum 16), p. 19–21.

- ↑ Rita Perry: Die Campanareliefs. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-1827-8 (Katalog der Sammlung antiker Kleinkunst des Archäologischen Instituts der Universität Heidelberg, Band 4), p. 52–53

- ↑ Siebert 2011 p. 28

- ↑ On the painting, see von Rohden and Winnefeld 1911, p. 26–29

- ↑ Siebert 2011 p. 30.

- ↑ The most famous example of this genre is the Nile mosaic of Palestrina.

- ↑ Rauch 1999, p. 202, 269

- ↑ Inventory # D 205; Harald Mielsch: Römische Architekturterrakotten und Wandmalereien im Akademischen Kunstmuseum Bonn. Mann, Berlin 1971, ISBN 3-7861-2195-8, p. 12 Nr. 7

- ↑ Rauch 1999, p. 2

- ↑ Inventory number 3839

- ↑ Kristine Bøggild Johannsen, "Campanareliefs im Kontext. Ein Beitrag zur Neubewertung der Funktion und Bedeutung der Campanareliefs in römischen Villen," Facta 22 (2008), p. 15–38

- ↑ Siebert 2011 p. 24–26

- ↑ Siebert 2011 p. 23

- ↑ Siebert 2011 p. 24

- ↑ Siebert 2011 p. 24–25

- ↑ Siebert 2011 p. 25

- ↑ Siebert 2011 p. 25–26

- ↑ Siebert 2011 p. 26

- ↑ Fragment of terracotta Campana relief: imitation Hieroglyphs, Egyptian-style figure to left

- ↑ Christian E. Loeben: Ein außergewöhnlicher Typ. Ägyptisches auf einer Terrakottaplatte in Siebert 2011 p. 68–73

- ↑ Siebert 2011 p. 74

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Campana Reliefs. |

- Literature by and about Campana reliefs in the German National Library catalogue