Caño Limón–Coveñas pipeline

| Caño Limón – Coveñas pipeline | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | |

| Country | Colombia |

| Province | Arauca Department, Norte de Santander Department, Sucre Department |

| From | Caño Limón oilfield |

| To | Coveñas |

| General information | |

| Type | crude oil |

| Owner | Ecopetrol, Occidental Petroleum |

| Commissioned | 1986 |

| Technical information | |

| Length | 780 km (480 mi) |

| Maximum discharge | 0.225 million barrels per day (~1.12×107 t/a) |

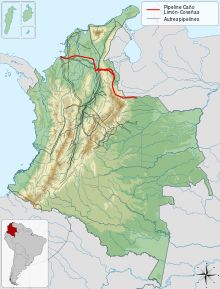

The Caño Limón – Coveñas pipeline is a crude oil pipeline in Colombia from the Caño Limón oilfield in the municipalities of Arauca and Arauquita in Arauca Department on the border of Venezuela to Coveñas on Colombia's Caribbean coastline. It is jointly owned by the state oil firm Ecopetrol, and U.S. company Occidental Petroleum. The pipeline is 780 kilometres (480 mi) long.

History

From the point of view of officials at Ecopetrol, developing petroleum reserves in Arauca seemed a great opportunity, especially with multinational petroleum companies willing to accept all or most of the apparent financial risks. Oil for export to the United States of America from South America was strategically important to the US in 1985-86 because of a general interest in decreasing dependency upon middle-eastern oil. Anti-Communist efforts by the US under President Ronald Reagan in Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Grenada suggest that it was important to the US to decrease Communist influences in Central and South America. The Colombian Government was, at that time, fighting a civil war on multiple fronts with Communist Guerrilla groups. From a private enterprise point of view, middle eastern crises propping up the price of oil made petroleum development in Colombia an attractive opportunity.

In that context, the discovery of significant oil reserves in Arauca, Colombia must have seemed a great opportunity to Occidental Petroleum as they negotiated contracts for exploration, oil field development, oil pipeline construction, and a oil tanker port at Coveñas, Colombia. Occidental Petroleum, Oxy, made many efforts to maintain a positive and helpful corporate image. The 1985 installation of the oil fields at Caño Limón flooded the local economy with currency, causing dramatic inflation reported by at least one economic study. Rumors of one particular Oxy executive opening a suitcase full of cash in a hotel lobby within view of many people suggest that wealthy foreign professionals recklessly publicized how much money they had.

The influx of workers placed significant pressure on local infrastructure, with compromised sanitation and other externality impacts not fully addressed by the petroleum project developers. This all took place in remote, under-developed towns and rural areas inhabited to a significant extent by families who identified with the Communist Party and had fled the urban areas of Colombia to escape La Violencia of the 1940's and 1950's. Many factors contributed to anti-government, xenophobic, anti-extraction-for-export, pro-Communist, and anti-US sentiments.

Many people in the community protested with "paros" in an effort to demand higher wages, as they faced three-figure localized inflation rates that made it difficult for them to meet their basic needs in spite of salaries which had seemed high when they were initially hired.

The pipeline, which opened in 1986, was plagued by similar challenges. Collaborative design-build efforts for the pipeline involved Bechtel Corporation, Occidental Petroleum, Ecopetrol, and local engineering companies. The pace of design and construction was unprecedentedly rapid for that area of the world. The physical scale and time goals of the project created a situation where engineering facts and contracts mattered more than concerns regarding the well-being of people and the environment. Pipeline project representatives are reported to have requested easements from cacao (chocolate tree) orchard owners, offering:

option a) a very low level of compensation insufficient to address their real economic loss or

option b)nothing, and the pipeline would be installed on their property within days anyway through an imminent domain process.

This reportedly caused local land-owners to claim they had been unfairly damaged by the project without just compensation for their losses. There was apparently no attractive remedy available through local courts for these land-owners to receive compensation from the companies for the liquidated damages caused to their orchards by the pipeline construction project.

Armand Hammer, head of Oxy, directed his staff to follow US environmental standards while operating in Colombia, yet it was difficult for them to control all of the environmental impacts. In one memorable case, engineers had designed secondary containment berms for storage tanks sufficient to hold the contents of the tank plus free-board. What they did not sufficiently address was floodwaters ouside the enclosure that rose high enough to over-top the berms and mobilize contaminants the berms were supposed to contain. It must have been difficult for engineers to fully anticipate the local hydrology and hydraulics working under such time constraints in areas not fully understood hydrologically. It also must have been equally difficult for managers to justify higher factors of safety on levee construction because of cost and time-related goals they were required to achieve. Environmental impacts from the project were significant.

These factors, and more, led to resentment toward the oil development project and its most vulnerable part: the pipeline.

By the third quarter of 1986, project operations had already suffered many losses, including:

1)theft of explosives used for oil exploration seismograph measurements and construction operations,

2)foreign engineers kidnapped for ransom,

3)the death of at least one foreign engineer/expert who died after being kidnapped, reportedly because he was not provided a personal

prescription medication by his captors, and

4)bombing of the pipeline as frequently as once per week, ostensibly by guerrilla groups who in many cases used the explosives they had stolen from earlier phases of the project.

Environmental impacts have intensified dramatically, due to pipeline ruptures that have caused some large scale oil spills in sensitive habitats such as large natural lakes. Such spills have been shrugged off by local officials who claim to have bioremediation technologies capable of making the oil spills benign. Such claims have not been sufficiently substantiated with chemical sampling and analysis of groundwater, surface water, and toxicity testing.

During its existence, the pipeline has often been attacked by guerrilla organizations that oppose the Colombian government. Even in the pipeline's first year, it was bombed as frequently as once per week.

The pipeline was opened in 1986. During its existence, the pipeline has often been attacked by guerrilla organizations that oppose the Colombian government. The National Liberation Army (ELN), which has traditionally been involved in such attacks, charged in a communique that "in our country, energy policy does not prioritize investment (in Colombia) but rather exploitation and consumption that sacrifices future generations." Together with the FARC, they have repeatedly sabotaged and exploded sections of the pipeline.

The Colombian government has militarized the area in response. For several years a security tax was imposed on oil producers in the region, which have also been targeted by guerrilla extortion and kidnappings. Occidental Petroleum also contracted the security firm AirScan to aid the Colombian military in the defense of its operations.

| Attacks on Oil Pipelines, 2001-2004 | ||||

| 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | |

| All pipelines | 263 | 74 | 179 | 103 |

| Caño Limón Coveñas | 170 | 41 | 34 | 17 |

| Source: Ministry of Defense, Government of Colombia. | ||||

In 2001, there were 170 attacks on the pipeline. The pipeline was out of operation for 266 days of that year. The government estimates that these bombings potentially reduced the GDP of Colombia by 0.5%. Occidental Petroleum lobbied and testified for increased American involvement in protecting the pipeline. The government of the United States increased military aid by $98 million, in 2003, to Colombia to assist in the effort to defend the pipeline. Attacks on the pipeline have subsequently been reduced during the following years.

In 1998, AirScan misidentified the village of Santo Domingo as a hostile guerrilla target, leading to a December 13 cluster bomb attack by the Colombian military which killed eighteen civilians, including nine children. The incident led to different legal actions against all the parties involved, some of which are still in progress.

See also

References

Sources

- Project Underground, "Blood of Our Mother", August 1998.

- Douglass W. Cassel Jr., "A CORPORATE COVER-UP?, Chicago Daily Law Bulletin, January 9, 2003.

- American Friends Service Committee, U.S. Military Aid and Oil Interests in Colombia.

- T. Christian Miller, A Colombian Village Caught in a Cross-Fire, Los Angeles Times, March 17, 2002.

- Bill Weinberg, STATE OF SIEGE IN ARAUCA: Indigenous Peoples, Civil Society Under Attack in Colombia's Oil Zone.