Peñarol

| |||

| Full name | Club Atlético Peñarol | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nickname(s) |

Manyas Aurinegros (Gold and Blacks) Carboneros (Coalmen) Mirasoles (Sunflowers) | ||

| Founded |

28 September 1891[1] as CURCC | ||

| Ground | Estadio Campeón del Siglo | ||

| Capacity | 40,000[2] | ||

| Chairman | Juan Pedro Damiani | ||

| Manager | Leonardo Ramos | ||

| League | Primera División | ||

| 2017 | 3rd | ||

| Website | Club website | ||

|

| |||

Club Atlético Peñarol (Spanish pronunciation: [kluβ aˈtletiko peɲaˈɾol]; English: Peñarol Athletic Club) —also known as Carboneros, Aurinegros and (familiarly) Manyas— is a Uruguayan sports club from Montevideo. The name "Peñarol" comes from the Peñarol neighbourhood on the outskirts of Montevideo.[3] Throughout its history the club has also participated in other sports, such as basketball[4] and cycling.[5] Its focus has always been on football, a sport in which the club excels,[6] having never been relegated from the top division.

In international competition, Peñarol is the third-highest Copa Libertadores winner with five victories[7] and shares the record for Intercontinental Cup victories with three.[8] In September 2009, the club was chosen as the South American Club of the Century by the IFFHS .[6]

History

Origins

Peñarol was founded on 28 September 1891 when employees of the Central Uruguay Railway Company established the Central Uruguay Railway Cricket Club (CURCC) of Montevideo, with the purpose of stimulating the practice of cricket, rugby football and "other male sports" (literal from the Spanish).

The Central Uruguay Railway company had operated in Uruguay since 1878,[3] with 118 employees, 72 British, 45 Uruguayan and one German.[9] The club was known as CURCC in the neighborhood of Peñarol—the latter from the Peñarol neighborhood, about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) from Montevideo,[3] whose name in turn derived from an Italian city. The club's first president Frank Henderson, who remained in that position until 1899.[10]

In 1892, the CURCC shifted its focus from cricket and rugby to association football.[11] The football club's first game was against a team of students from the English high school and ended with a 2–0 victory.[9] In 1895, Uruguayan footballer Julio Negrón was chosen as the team's first non-British captain.[12]

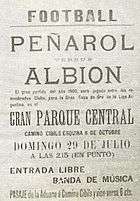

First CURCC titles

In 1900 the CURCC was one of four charter members of the Uruguay Association Football League,[13] making its debut in official competition on 10 June against Albion and winning 2–1.[14] The club won its first Uruguayan championship that year, repeating in 1901, 1905 and 1907. In 1906 Charles W. Bayne took over the railroad, and refused to sponsor the football team due to financial and work issues. Conflict between the company and the football club led to the severance of their relationship in 1913.[15]

In 1908, the club left the Uruguayan league after the league rejected their request to replay a game with F.C. Dublín. CURCC had lost 2–3 on the road, and believed their poor showing was due to refereeing mistakes caused by pressure from rabid home fans. As a sign of good faith, Nacional also retired from the league, since both teams agreed that " Los Partidos se ganan en la Cancha ", or the games are won in the field.[13] Back in competition the following year, relations between the CUR and the club became frostier after fans burned a train car used for rival teams.

A year after the club's 1911 Uruguayan championship, the club attempted reforms to its policies. Proposals included greater participation by non-CUR players and a name change to "CURCC Peñarol". In June 1913, the proposals were rejected; the company wanted to distance itself from the club's local reputation. The railroad company, decided to separate the " foot-ball " section of the team from the company on Saturday 13 December 1913. That is when Peñarol was founded. The following day it was the first time a " Clasico " was officially played between Nacional and Peñarol.[16]

CURCC kept playing football in the amateurism until it was dissolved on 22 January 1915 and donated all their trophies to the British Hospital of Montevideo, not to Peñarol.

C.A. Peñarol

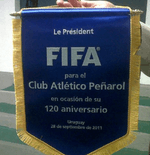

The club was congratulated on its 120th anniversary in September 2011 by presidents Joseph Blatter, Michel Platini.[17] and Nicolás Leoz.[18]

On 12 March 1914, Peñarol replaced CURCC's spot in the Uruguayan Football League after its foundation in 1913. A request submitted to the Uruguayan Football League two days later and approved the following day.[9] During its first years Peñarol was not successful, although a new stadium (Las Acacias) opened on 19 May 1916.[19] The club won its first two league titles in 1918 and 1920.

In November 1922 the Asociación Uruguaya de Fútbol (AUF) disqualified Peñarol because the club played an exhibition game with the Racing Club de Avellaneda, a club affiliated with the Asociación Amateurs de Football in Argentina and not the Asociación Argentina de Football.[20] Peñarol and other clubs then organised a new league, the Uruguayan Football Federation (FUF), and the club won the 1924 championship.[20] The league was short-lived; Peñarol won the 1926 Copa del Consejo Provisorio, triggering a merger between the AUF and the FUF.[21]

After its first European tour in 1927, Peñarol won the Uruguayan championship in 1928 and 1929; the following year, the club defeated Olimpia 1–0 in its first game at the Centenario Stadium in Montevideo.

Consolidation

In 1932, Peñarol and River Plate played the first game of the professional era. Peñarol won the first Uruguayan professional championship with 40 points, five more than runners-up Rampla Juniors.[22] After placing second in 1933 and 1934, the club won four consecutive league tournaments between 1935 and 1938; they also won the 1936 Torneo Competencia.

The club stayed in second place until 1944, when Peñarol again won the Uruguayan Championship (defeating Nacional in a two-game final, 0–0 and 3–2).[23] In 1945 the club retained the title, with Nicolás Falero and Raúl Schiaffino the top goal scorers of the playoffs with 21 apiece.[24] Peñarol was again victoious in 1949, four points ahead of runner-up Nacional with Óscar Míguez the top scorer.[25]

After placing second in 1950, Peñarol won the Uruguayan Championship the following year;[26] this was also the start of the Palacio Peñarol's four-year construction. During the 1950s, the club also won national championships in 1953,[27] 1954,[28] 1958[29] and 1959.[30]

International success

Their 1959 championship qualified Peñarol for the recently created Copa Libertadores, an international competition then known as the Copa de Campeones de América. Peñarol won the first two tournaments, beating Olimpia of Paraguay in 1960[31] and Palmeiras of Brasil in 1961.[32] That year the club won its first Intercontinental Cup, defeating Benfica of Portugal 2–1 in the third game.[33] Peñarol won three more league titles (1960, 1961 and 1962), for five consecutive championships.

After a quiet year in 1963, Peñarol won the Uruguayan Championship in 1964 and 1965 and the Copa Libertadores in 1966, defeating River Plate 4–2.[34] That year the club won its second Intercontinental Cup, defeating Real Madrid 2–0 in Centenario Stadium and Santiago Bernabéu.[35] During the next few years the club won national championships in 1967 and 1968 and the Intercontinental Champions' Supercup in 1969 (a tournament with South American Intercontinental Cup winners). Peñarol had the longest undefeated run in Uruguayan league history: 56 games, from 3 September 1966 to 14 September 1968.[36] Copa Libertadores all-time top scorer Alberto Spencer played for Peñarol at this time.

In 1970 the club again reached the Libertadores final again, losing to Estudiantes de La Plata. The club set a tournament record for greatest goal difference, defeating Valencia of Venezuela 11–2. With Fernando Morena as the team's star, the club won the Uruguayan championship for three consecutive years, from 1973–75. After placing second in 1976 and 1977, Peñarol won again in 1978. That year, Morena set two records: most goals scored in a Uruguayan season (36)[37] and most goals scored in a single game (seven, against Huracán Buceo on 16 July).[38] The 1970s ended with another championship in 1979. Morena was top scorer in the Uruguayan tournament six straight times, and top Copa Libertadores scorer in 1974 and 1975.

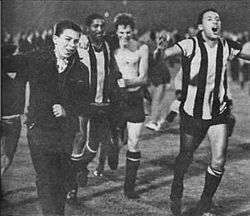

After beginning the 1980s with a third-place finish in 1981, Peñarol won the Uruguayan Championship with Fernando Morena and Rubén Paz (the tournament's top scorer). The next season the club again won the Copa Libertadores, defeating Cobreloa of Chile 1–0 on a goal from Fernando Morena[39] (the tournament's top scorer with seven goals) in the game's final minutes. Later that year the club won the Uruguayan championship and its third Intercontinental Cup, defeating Aston Villa 2–0.[40]

Despite financial problems during the 1980s, Peñarol won the national championship in 1985 and 1986, and a fifth Copa Libertadores in 1987. The club defeated América de Cali 1–0 with a goal by Diego Aguirre in the final seconds of extra time, when a tie would have gone to the Colombians on the goal differential.[41] It was the third Copa Libertadores won by Peñarol at the Nacional de Chile, following victories in 1966 and 1982.

Peñarol celebrated its hundredth anniversary in 1991, despite a controversy ignited by archrivals Nacional concerning Peñarol's 1913 name change. With Pablo Bengoechea and the young Antonio Pacheco on the team and Gregorio Pérez behind the bench, Peñarol again won the Uruguayan championship five straight times (1993–97).[42] The club also reached the Copa Conmebol final in 1994 and 1995, rounding out the century with a national championship in 1999 (defeating Nacional 2–1 in the final, despite Julio Ribas on the bench).

The next year, Peñarol lost the Uruguayan championship final against Nacional; many of the team's players were jailed after a tournament fight.[43] Peñarol won the national championship again in 2003 for Diego Aguirre, defeating Nacional in the final. The club did not win another national title until the 2009–10 season, when it won the Clausura tournament with 14 victories in 15 games (12 of them in a row). In the Clausura final, Peñarol defeated Nacional 2–1. The championship qualified the team for the Libertadores 2011, where Peñarol reached the final with Santos.[44]

Crest and colors

Badge

Throughout the club's history minor changes have been made to its symbols, but it has kept its original colors. The shield and flag were designed by architect Constante Facello and consist of five black stripes, four yellow stripes and eleven yellow stars on a black background (representing the eleven players).[45]

|

|

Badge evolution

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Uniforms

.jpg)

Since its founding, Peñarol's colors have been yellow and black. They were inspired by the Rocket locomotive designed by George Stephenson, which won an award in 1829.[10]

The first jersey was a plain shirt, divided into four square sections which alternated black and yellow.[46] A variant had two vertical halves (black on the right and black-and-yellow stripes on the left), with black shorts and socks. Peñarol's official jersey (black and yellow stripes) dates back to 1911[47] and has been worn almost continuously, with only slight variations.[48]

|

1891–96 |

1896–05 |

1905–10 |

1911–present |

The first alternate uniform is believed to have been a squared jersey, similar to the club's first main shirt but with orange instead of yellow. In 1984 a jersey with horizontal stripes (instead of vertical) was worn, and 1987 featured a yellow jersey with black shorts. Other alternate uniforms (used recently) have been completely black, grey or yellow. Special jerseys have been worn for international friendlies, especially during the 1960s. The CURCC's main uniform (with two-halves, one plain and one striped) is used as a third uniform. On 4 February 2013 all-black and all-yellow alternate uniforms were introduced.[49]

1913 |

1970[note 2] |

1970[note 3] |

1971[note 4] |

|

1984 |

(1) See below |

1995–09 |

2004–08 |

2010–11 |

|

1996–97, 2001, 2009–11 |

1999[note 5] |

2011[note 6] |

2014[note 7] |

Kit manufacturers

| Period | Company |

|---|---|

| 1979–84 | |

| 1984–87 | |

| 1987–1988 | |

| 1988–1991 | |

| 1991–1996 | |

| 1996–1998 | |

| 1998–1999 | |

| 2000 | |

| 2001-2006 | |

| 2006- | |

Facilities

Stadium

.jpg)

Peñarol's stadium is the José Pedro Damiani, also known as Las Acacias. It was bought in 1913 and inaugurated on 19 April 1916 with a 3–1 victory over Nacional.[51] The stadium's gate was that of the former Estadio Pocitos, Peñarol's first stadium where the first goal in the history of the FIFA World Cup was scored in 1930.[52]

The stadium is in the Marconi neighbourhood of Montevideo. Its pitch is of 37,949 square metres (408,480 sq ft), and it has a capacity of 12,000.[51] Because Peñarol is not allowed to play there,[53] the club home ground is the city owned Estadio Centenario. Opened on 18 July 1930, the Centenario stadium is located in Parque Batlle and can hold 65,235.[54]

On 28 September 2012, the club proposed a 40,000-capacity stadium in the outskirts of Montevideo, about 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) from the Aeropuerto Internacional de Carrasco.[55] The name of their newest stadium is Campeón del Siglo, with the opening in March 2016.

Palacio Peñarol

The Palacio Peñarol, in downtown Montevideo, is the club's headquarters and basketball stadium. It was opened on 21 June 1955;[56] and is located. The Palacio has 3,896 square metres (41,940 sq ft) in addition to basketball, it is home the club's museum and offices.[57] After the October 2010 collapse of the Cilindro Municipal, the Palacio Peñarol became an important venue for Uruguayan basketball.[58]

Complejo Deportivo Washington Cataldi

The Complejo Deportivo Washington Cataldi, commonly known as Los Aromos, is a training ground for the main team.[59] In Villa Los Aromos of Barros Blancos, in the Canelones department, Los Aromos was bought in 1945; under the direction of architect José Donato, it was built in two years.[60]

Centro de Alto Rendimiento

For the club's 118th anniversary, the Centro de Alto Rendimiento was inaugurated. The new facility, which opened on 28 September 2009, includes five football pitches, a weight room and a gymnasium with artificial turf.[61]

Frank Henderson School

The Frank Henderson School, named in honor of the club's first president, is a few kilometers away from the Centro de Alto Rendimiento. It was built to develop the club's young players, and houses those who come from other areas.[62]

Supporters

In Uruguayan football, loyalty to Peñarol or Nacional divides the country. The clubs are evenly matched, and have a large fan base. Many surveys of public opinion have been conducted, but none have been conclusive. In 1993 the Factum consulting firm reported that Peñarol was the favorite team of 41 percent of football fans, while 38 percent supported Nacional.[12] Factum conducted another survey in 2006, confirming its previous results: Peñarol with 45 percent and Nacional with 35 percent.[63]

MPC Consultants surveyed 9,000 Uruguayans; Peñarol had 45 percent of the supporters, and Nacional 38 percent. An online survey on the webpage Sportsvs.com showed Nacional with 50.35 percent and Peñarol with 49.45 percent.[64]

Since its formation, Peñarol's barra brava has been involved in violence against other clubs and the Uruguayan police. Incidents provoked by these fans have cost Peñarol 31 points since 1994; the penalties cost the team three tournaments (Apertura 1994,[65] Clausura 1997[66] and Clausura 2002).[67]

Fan club

In 2010 the club attempted to increase its fan base to improve its sustainability. During Clausura 2010 promotions were offered, marketing managers hired and the peñas (local fan clubs) encouraged. The campaign was successful; in February 2013 the club had over 62,000 members, the largest fan club in Uruguay.[68]

Rivalries

The Uruguayan Derby between Peñarol and Nacional goes back to 1900, the oldest football rivalry outside the British Islands.[69] The first game ever played between Nacional and CURCC was on 15 July 1900 and ended 2–0 in favor of CURCC. CURCC was ahead at first, but Nacional caught up during the late 1910s. Nacional took the lead by fourteen games in 1948, and would not surrender it until the late 1970s (except briefly in 1968). Since then, Peñarol has been the leader; its longest lead was 26 games in January 2004.[70] Including the amateur and professional eras, league and friendly games, the teams have met 511 times in the past with 182 victories to Peñarol, 166 to Nacional and 163 ties.[70]

A notable game for Peñarol fans is occurred on 9 October 1949 in the Uruguayan Cup first round, and is known as the Clásico de la fuga (the "escape derby"). At the end of the first half Peñarol was leading 2–0, but at halftime Nacional decided not to return. While Peñarol fans believe that Nacional did not want to be defeated by a Peñarol team known as the Máquina del 49 ("Machine of 49"), Nacional supporters claim it was a protest against poor officiating.[71]

On 23 April 1987 for a friendly game, Peñarol and Nacional were tied 1–1 with 22 minutes remaining when three Peñarol players (José Perdomo, José Herrera and Ricardo Viera) were ejected after a foul and subsequent protests. Peñarol then had to face a full Nacional team with only eight players on the pitch. With eight minutes remaining Diego Aguirre set up Jorge Cabrera, who scored the winning goal. This win by the aurinegro was known as the Clásico de los 8 contra 11 (the "8 against 11 derby").[72]

Peñarol and Nacional have faced each other in the final game of the Uruguayan Championship thirteen times, with Peñarol winning eight. The most recent was in 2015, when Nacional won the championship 2–1.[70]

Manyas: The Movie

In early October 2011 Manyas: The Movie, a documentary about Peñarol's fans, was released in Uruguay. Produced by Kafka Films and Sacromonte and directed by Andrés Benvenuto, the film features interviews with fans, football journalists, psychologists and politicians.[73] Manyas: The Movie was deemed of cultural interest by the Culture and Education Ministry of Uruguay and of ministerial interest by Uruguay's Ministry of Tourism and Sport.[73] The film had the most-successful premiere of any Uruguayan film,[74] selling 13,000 tickets during its first weekend[75] and 30,000 over its first fifteen days.[76]

World's Biggest flag

After raising $35,000 in raffles and donations, on 12 April 2011 Peñarol fans unveiled the largest flag ever unfurled in a stadium up to that moment. Nacional unfurled a bigger one years later that covered three stands of the stadium. The flag, 309 metres (1,014 ft) long and 46 metres (151 ft) wide for a surface area of 14,124 square metres (152,030 sq ft), covered one-and-a-half grandstands in Centenario Stadium.[77] In 2013, Club Nacional de Football displayed a flag which was 600 metres long by 50 metres wide. This is now the world's biggest flag.

Players

First-team squad

- As of 12 August 2017

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Noted players

Néstor Gonçalves has the most official games in the club's history (571 matches, between 28 April 1957 and 28 November 1970. The team's all-time top scorers in the Primera División are Fernando Morena (203), Alberto Spencer (113) and Óscar Míguez (107). Morena's (whose 230 goals—203 with Peñarol and 27 with River Plate—make him the highest-scoring player in the Uruguayan League) 440 goals with Peñarol are a record as well. He scored the most goals in a single Uruguayan season (36 in 1978), and is the club's second-best goal scorer in international competition with 37 goals (behind Alberto Spencer, who scored 58 goals between 1960 and 1970). Spencer and Morena are the top scorers in Copa Libertadores history,[78] with 48 and 37 goals respectively for Peñarol.[note 8]

Peñarol has made a large contribution to the Uruguayan national football team. Three Peñarol players were on the Uruguayan team which played Argentina in 1905.[79] Five Peñarol players were on the Uruguayan squad which won the 1930 FIFA World Cup: goalkeeper Miguel Capuccini, defender Peregrino Anselmo and midfielders Lorenzo Fernández, Álvaro Gestido and Carlos Riolfo.[80] Peñarol had nine players on the Uruguayan squad which won the 1950 FIFA World Cup: goalkeeper Roque Máspoli, defenders Juan Carlos González and Washington Ortuño, midfielders Juan Alberto Schiaffino and Obdulio Varela and forwards Ernesto Vidal, Julio César Britos, Óscar Míguez and Alcides Ghiggia.[80] Schiaffino and Ghiggia scored the team's two goals in the Maracanazo, the final game against Brasil.[81] Peñarol is the only club which has represented Uruguay in all its World Cup appearances.[82]

Managers

While there is no hard information about managers in the amateur era of Uruguayan football, Peñarol has had a total of 62 coaches during its professional era. The first manager was Leonardo de Luca, who coached the team for two years and won the Uruguayan Championship (the first professional tournament in Uruguay) in 1932.

Of these 62 managers, 53 were Uruguayan; two were Hungarian (Emérico Hirschl and Béla Guttmann), two British (John Harley and Randolph Galloway), one Serbian (Ljupko Petrović), two Brazilian (Osvaldo Brandão and Dino Sani), one from Chile (Mario Tuane) and two from Argentina (Jorge Kistenmacher and César Luis Menotti).

Hugo Bagnulo and Gregorio Pérez have coached Peñarol the longest, leading the first team for eight seasons: Bagnulo for four stints and Pérez for five. Athuel Velásquez had the longest uninterrupted coaching period for Peñarol (five straight years, between 1935 and 1940). Bagnulo has the most Uruguayan championships (five); Pérez and Velásquez follow, with four each. In international competition Roberto Scarone was the most successful manager, winning two Copa Libertadores and an Intercontinental Cup with Peñarol.[83][84]

Professional-era managers

Caretaker managers in italics

|

|

|

Current staff

- Coach: Leonardo Ramos

- Assistant coaches: Marcelo Suárez

- Trainers: Matías Eijo, Sebastián Roquero

- Goalkeepers' coach: Óscar Ferro

- Physiotherapist: Sebastián Arbiza

- Kinesiologists: Miguel Domínguez, Héctor Peña

Administration

During a meeting presided over by Roland Moor on 28 September 1913, it was stipulated that responsibility for the Central Uruguay Railway Cricket Club would belong to the principal administrator of the Central Uruguay Railway Company of Montevideo. The first president of the club was Frank Henderson, who remained in that office until 1899.[10]

After Henderson CUR administrators remained as chairmen of the sports club until 1906, when Charles W. Bayne took over the CUR. Bayne refused to sponsor the CURCC because of vandalism by fans and absenteeism by workers. He was replaced by CUR employee Roland Moor.[15]

Conflicts remained between the company and the sports club, which resulted in the separation of CURCC's football section from the company and a name change to Club Atlético Peñarol.[15] Jorge Clulow, an Englishman with Uruguayan nationality, was chosen chairman of the club; he remained in office from 1914 to 1915.[83][85]

Presidents

|

|

Honorary

|

Board members 2011–14

The most recent elections took place in November 2011. Juan Pedro Damiani remained as president of the club, with 58 percent of the votes. Aside from the president, ten other board members were elected. While the list "10" obtained seven board positions, the "2809" took three, and the "2011" one.[86][87]

| Position | Name |

|---|---|

| President | Juan Pedro Damiani |

| Vice President | Edgar Welker |

| General secretary | Gervasio Gedanke |

| Pro Secretary | Ricardo Rachetti |

| Treasurer | Walter Pereyra |

| Pro Treasurer | Rodolfo Catino |

| Honorary accountant | Juan Fernández Methol |

| General institutional coordinator | Carlos Casarotti |

| Advisors | Julio Luis Sanguinetti |

| Daniel Viñas | |

| Isaac Alfie | |

| Carlos Scherchener | |

| AUF delegates | Jorge Barrera |

| Jorge Campomar | |

| Sports manager | Carlos Sánchez[88] |

| Marketing manager | Pablo Nieto[89] |

| General manager | Álvaro Alonso[89] |

| Ombudsman | Fernando Morena[90] |

Statistics

Amateur era

Peñarol played 26 seasons of the Uruguay Association Football League, from its creation in 1900 until the end of the amateur era in 1931 (absent 1923–26, when the club was disaffiliated from the AUF).[91] During this period Peñarol won the Uruguayan Championship nine times, with its best years in 1900 and 1905[92] (when the club won the championship without conceding any points). Peñarol was undefeated in 1901,[93] 1903[94] and 1907.[note 10][95] Its worst year was 1908; the team left the league after ten games, forfeiting the other eight.[96] Peñarol's largest goal difference in a game during its amateur era was in 1903, when they defeated Triunfo 12–0.[97]

The club placed second in 1923 (when they scored a record 100 goals), and won in 1924; its most impressive victory was a 10–0 win over Roberto Cherry during the cancelled 1925 season.[97]

Professional era

Since the beginning of the professional era in 1932, Peñarol and Nacional are the only teams who have played every season for the Uruguayan championship.[note 11][98] Peñarol has the most Uruguayan League titles (winning 38 times between 1932 and 2013) and the greatest number of undefeated championships (1949, 1954, 1964, 1967, 1968, 1975 and 1978).[99] Its best performances were in 1949 and 1964, seasons when the team scored 94.44 percent of possible points; its worst season was 2005–06, when it finished in 16th place after winning 32.32 percent of possible points.[100] A 12-point deduction given the team by the AUF because of unrest after a game with Cerro relegated them to that position.[101]

Peñarol's best victory was a 9–0 win against Rampla Juniors in 1962; its worst defeat was 0–6 against Nacional. On the international scene, its best result was an 11–2 win over Valencia of Venezuela on 15 March 1970; its worst was against Olimpia of Paraguay, a 0–6 loss on 10 December 1990 during the Supercopa Sudamericana.

Peñarol holds a number of national and international records. The club has the longest undefeated run in the Uruguayan league: 56 games, from 3 September 1966 to 14 September 1968.[36] This is also the longest undefeated run in South American professional football (second place if amateur leagues are counted).[102]

It was the first club to win the Copa Libertadores de América undefeated, in 1960.[103] Peñarol has the greatest number of appearances in the Copa Libertadores (40),[104] and the most appearances in the finals (10).[104] The club holds the record for the biggest win (11–2 against Valencia),[103] and the biggest goal difference in a two-legged elimination (defeating Everest from Ecuador 5–0 and 9–1).[103] Peñarol is one of the teams with five Intercontinental Cup appearances, the first to reach that number.

Honours

National

- Primera División (AUF) (48): 1900, 1901, 1905, 1907, 1911;[note 12] 1918, 1921, 1928, 1929, 1932, 1935, 1936, 1937, 1938, 1944, 1945, 1949, 1951, 1953, 1954, 1958, 1959, 1960, 1961, 1962, 1964, 1965, 1967, 1968, 1973, 1974, 1975, 1978, 1979, 1981, 1982, 1985, 1986, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1999, 2003, 2009–10, 2012–13, 2015–16

- Primera División (FUF/CP) (2): 1924 FUF, 1926 CP[note 13]

International

- Intercontinental Cup (3): 1961, 1966, 1982[8]

- Copa Libertadores (5): 1960, 1961, 1966, 1982, 1987[7]

- Intercontinental Champions' Supercup (1): 1969[105]

- Copa de Honor Cousenier (AFA/AUF)[note 14] (3): 1909, 1911,[note 12] 1918[106]

- Tie Cup (AFA/AUF)[note 14] (1): 1916[107]

- Copa Aldao (AFA/AUF)[note 14] (1): 1928[108]

Friendly international

- Mohammed V Trophy (1): 1974

- IFA Shield (IFA)[note 15] (1): 1985[109]

South American Club of the Century

In 2009, the International Federation of Football History & Statistics, not FIFA, released a list of the best clubs of the 20th century on each continent. The organization awarded points for each victory in a quarterfinal or higher in international competition but only took into account games played after 1932 for the Professional era. Peñarol was the number-one team in South America, above Independiente of Argentina and Nacional of Uruguay.

| Rank | Team | Country | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Peñarol | Uruguay | 531 |

| 2 | Independiente | Argentina | 426.5 |

| 3 | Nacional | Uruguay | 414 |

| 4 | River Plate | Argentina | 404.25 |

| 5 | Olimpia | Paraguay | 337 |

| 6 | Boca Juniors | Argentina | 312 |

| 7 | Cruzeiro | Brazil | 295.5 |

| 8 | São Paulo | Brazil | 242 |

| 9 | América de Cali | Colombia | 220 |

| 10 | Palmeiras | Brazil | 213 |

Other sports

Basketball

Peñarol's basketball records date back to the late 1920s, when Club Piratas was formed; in 1931, it became Peñarol.[4] Its first league game (in the fourth division of Uruguayan basketball) was played in 1940. By 1943 the team, playing in the first division for Ramón Esnal, finished third. The following year Peñarol won the Federal Championship, a tournament attracting the best basketball teams in Montevideo; in 2003, the league changed its name to Liga Uruguaya de Basketball.

In 1945, Peñarol jumped from the Uruguayan Basketball Federation to play in a new league;[4] when the upstart league failed, the club rejoined the federation in 1947. In 1952 Peñarol again won the Federal Championship, winning the Winter Tournament in 1953 and 1955.[110] After a low period (with relegation in 1968), Peñarol won the Uruguayan Championship in 1973, 1978, and 1979;the latter was the first professional tournament in league history.[4] In 1982 the club enjoyed its most successful season, winning the Federal Championship and[4] the Winter Tournament[110] The club also won the Campeonato Sudamericano de Clubes in 1983. In 1985 the club was relegated, beginning a downward spiral which ended with its expulsion from the league in 1997.[4]

Cycling

Peñarol has participated in the Vuelta Ciclista del Uruguay (Tour of Uruguay) since it began in 1939. Although the team rode well during its early years, it was not until the ninth edition (in 1952) that a Peñarol cyclist would win the race (Dante Sudatti, with an overall time of 48 hours, 38 minutes and 38 seconds). Peñarol cyclists also won the general classification 1953 and 1956; in the latter year, the club won the team championship.

After again winning the team championship in 1959, Peñarol would only win one individual championship in 1964. The team later improved, winning three individual titles in a row from 1989 to 1991 and the team victory in 1990 and 1991. 2002 was the fourth year that the club won both the individual and team classifications.[5] Peñarol has competed in other road races, including José María Orlando's 1990 victory in the Rutas de América.[111]

Futsal

Peñarol began playing futsal in 1968. During its first two decades, the club won on the national and international levels (including a victory in the 1987 World Interclub Championship). In 1995 FIFA took over the sport, and Peñarol began competing in AUF tournaments. The team won the first three Uruguayan Championships (1995, 1996, and 1997), also finishing at the top in 1999 and 2004. It won another three consecutive tournaments in 2010, 2011 and 2012.[112]

Beach soccer

In January 2013 Peñarol inaugurated its beach soccer section.[113] Diego Monserrat, goalkeeper of the Uruguay national team for many years, was the institution's first coach in this sport, while also goalkeeper Felipe Fernández was the club's first captain.[113] On the second half of the same month, Peñarol won one of the three groups of five teams, that formed the qualification tournament to the "Super Liga", name given to the Uruguayan Championship of the discipline.[114] After victories on quarterfinals and semi-finals, Peñarol was declared champion of the tournament without the need of a final, after the other semi-final was suspended.[115]

Notes

- ↑ Worn against Club Atlético Atlanta of Argentina.

- ↑ Worn against Club Guaraní of Paraguay.

- ↑ Worn against Estudiantes de La Plata of Argentina.

- ↑ Worn against FK Inter Bratislava.

- ↑ 108 anniversary vs San Lorenzo.

- ↑ 120 anniversary vs San Lorenzo.

- ↑ 123 anniversary vs River Plate.

- ↑ Alberto Spencer scored 54 times in the Copa Libertadores, 48 with Peñarol and 6 with Barcelona.

- ↑ Year denotes receipt of award

- ↑ Moreover, in 1903 CURCC did not lose during the regular season, but lost the tiebreaker final against Nacional 2–3.

- ↑ In 1948 the tournament was cancelled because of a player strike.

- 1 2 Titles won as CURCC

- ↑ CP for "Consejo Provisorio", an unification tournament after the FUF was dissolved and its clubs returned to the AUF.

- 1 2 3 Established before CONMEBOL was created, this Cup was organized by the Argentine and Uruguayan Associations, between teams that belonged to them.

- ↑ Fourth oldest club cup, organized by the Indian Association and played between Indian clubs and other invited ones.

References

- ↑ Conmebol (ed.). "Guía de Clubes Sudamericanos" (PDF) (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 May 2012. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ↑ http://www.worldofstadiums.com/south-america/uruguay/estadio-campeon-del-siglo/

- 1 2 3 Ana Pais (2008). El País, ed. "Convierten a Peñarol en "museo vivo" con 3 millones de euros" (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 www.urubasket.com, ed. (2008). "Campeonato de Primera División" (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- 1 2 Cyclingnews.com, eds. (2005). "62nd Vuelta Ciclista al Uruguay" (in Spanish). Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- 1 2 IFFHS, ed. (2009). "El Club del Siglo de América del Sur". Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- 1 2 Karel Stokkermans (2010). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Copa Libertadores de América". Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- 1 2 Loris Magnani; Karel Stokkermans (2005). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Intercontinental Club Cup". Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- 1 2 3 Emilio Tacconi (2009). Revista Raíces, ed. "Historia del barrio "Peñarol"" (in Spanish). Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- 1 2 3 Administración Nacional de Correos, ed. (2001). "110 Años del Club Atlético Peñarol" (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- ↑ urugol.com, ed. (28 September 2011). "... Y llegó a los 120" (in Spanish). Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- 1 2 Juan Carlos Luzuriaga (2005). EFE deportes Revista Digital – Buenos Aires – Año 10 – N° 88, eds. "La forja de la rivalidad clásica: Nacional-Peñarol en el Montevideo del 900" (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- 1 2 Edgardo de Léon; Walter Zunino (2008). IFFHS, ed. "Uruguay – 1900 season". Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- ↑ Juan Carlos Luzuriaga (2008). EFE deportes Revista Digital – Buenos Aires – Año 13 – N° 120, eds. "Albion Football Club: profetas del sport en Uruguay" (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- 1 2 3 Ana Ribeiro; Raúl Cheda; Silvia Sosa; José Carlos Tuñas; Alejandra Carnejo; Malte Fernández; Leonardo Haberkom (2008). Intendencia Municipal de Montevideo, ed. "Barrio Peñarol – Patrimonio industrial ferroviario" (PDF) (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- ↑ Álvarez, Luciano (2010). Historia de Peñarol (in Spanish). Montevideo: Aguilar. p. 965.

- ↑ Unoticias.com.uy, eds. (26 September 2011). "Jugar con Torres me da otro aire y facilita muchas cosas" (in Spanish). Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ↑ Conmebol.com, eds. (28 September 2011). "La Conmebol congratula a Peñarol en su 120º aniversario" (in Spanish). Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ↑ La República, eds. (26 August 2007). "Un estadio que lleva su nombre" (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- 1 2 Futbolea.com (eds.). "Club Atlético Peñarol: Historial del Club" (in Spanish). Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- ↑ La República, eds. (11 June 2003). "Tres equipos amateurs ganaron todos los puntos" (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ↑ Diego Antognazza; Martín Tabeira (2004). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Uruguay 1932". Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- ↑ Diego Antognazza; Diego Cervini; Martín Tabeira (2004). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Uruguay 1944". Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- ↑ Diego Antognazza; Diego Cervini; Martín Tabeira (2004). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Uruguay 1945". Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- ↑ Diego Antognazza; Diego Cervini; Martín Tabeira (2004). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Uruguay 1949". Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- ↑ Diego Antognazza; Diego Cervini; Martín Tabeira (2004). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Uruguay 1951". Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- ↑ Diego Antognazza; Diego Cervini; Martín Tabeira (2004). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Uruguay 1953". Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- ↑ Diego Antognazza; Diego Cervini; Martín Tabeira (2004). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Uruguay 1954". Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- ↑ Diego Antognazza; Diego Cervini; Martín Tabeira (2004). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Uruguay 1958". Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- ↑ Diego Antognazza; Diego Cervini; Martín Tabeira (2005). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Uruguay 1959". Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- ↑ John Beuker; Osvaldo Gorgazzi (2002). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Copa Libertadores de Améria 1960". Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ↑ José Luis Pierrend; John Beuker; Osvaldo Gorgazzi (2002). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Copa Libertadores de Améria 1961". Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ↑ FIFA. "Copa Intercontinental 1961" (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ↑ José Luis Pierrend; Karel Stokkermans; John Beuker (2001). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Copa Libertadores de Améria 1966". Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ↑ FIFA. "Copa Intercontinental 1966" (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- 1 2 Diego Antognazza (2006). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Peñarol's series of 56 matches unbeaten in the Primera División Profesional". Retrieved 2008. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Martín Tabeira (28 October 2010). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Uruguay – League Top Scorers". Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- ↑ ElPais.com.uy (16 July 2008). "Hoy se cumplen 30 años de los 7 goles de morena" (in Spanish). Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- ↑ La República, eds. (1 December 2005). "Aniversario de la Copa Libertadores 1982" (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ↑ FIFA. "Copa Toyota 1982" (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ↑ Karel Stokkermans (24 April 2001). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Copa Libertadores de América 1987". Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- ↑ Karel Stokkermans (2009). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Uruguay – List of Champions". Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ ElPais.com, eds. (12 December 2000). "Del césped a la cárcel" (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ↑ ESPN Deportes.com (22 June 2011). "Santos venció a Peñarol y se coronó campeón de la Libertadores" (in Spanish). Retrieved 24 June 2011.

- ↑ futboldeaca.com (eds.). "Peñarol – Historia" (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ↑ elobservador.com.uy, eds. (28 September 2011). "La noche inolvidable de Peñarol" (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ Girasolweb.com (eds.). "Camisetas" (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ↑ todosobrecamisetas.net (21 January 2010). "Peñarol Presenta sus Nuevas Camisetas Puma para el 2010" (in Spanish). Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ↑ ElObservador.com.uy, eds. (5 February 2013). "El aurinegro presentó sus pilchas nuevas" (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ↑ "'Los uruguayos están locos", decía Spencer que quería volver a Ecuador" by Atilio Garrido on PasiónLibertadores website, 6 April 2012

- 1 2 peñarol.org (eds.). "Estadio "Cr. José Pedro Damiani"" (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ↑ cbc.ca, eds. (25 November 2009). "The World Cup's 1st goal scorer". Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ↑ La República, eds. (2 November 2006). "Gestiones con dirigentes de Progreso" (in Spanish). Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- ↑ EstadioCentenario.com.uy, eds. (January 2008). "Detalle de capacidad locativa por tribunas" (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ↑ estadiocap.com.uy. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ↑ 180.com.uy, eds. (21 January 2011). "El Palacio del básquetbol" (in Spanish). Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ↑ peñarol.org (eds.). "Palacio "Cr. Gastón Güelfi"" (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ↑ WebDeportiva.com.uy, eds. (20 March 2012). "Hebraica pasó por paliza" (in Spanish). Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ↑ urugol.com (eds.). "Los Aromos" (in Spanish). Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ↑ peñarol.org (eds.). "Complejo Deportivo "Washington Cataldi"" (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ↑ ultimasnoticias.com.uy, eds. (28 September 2009). "Peñarol tiene un Complejo de U$S 2.000.000" (in Spanish). Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ↑ peñarol.org (eds.). "El Colegio "Frank Henderson"" (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ↑ El Observador, ed. (2006). "Peñarol no es la mitad más uno" (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ↑ elobservador.com.uy, eds. (29 November 2010). "Nacional ganó la encuesta de Sportsvs.com" (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ Ian King (2001). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Uruguay 1994". Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- ↑ Javier Ferrando (1999). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Uruguay 1997". Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- ↑ Francisco Fernández (2003). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Uruguay 2002". Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- ↑ Tenfield.com.uy, eds. (4 March 2013). "Peñarol: El Cura Gonzalo Aemilius es el socio 60.000" (in Spanish). Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ↑ FIFA, ed. (2009). "Peñarol – Nacional, una rivalidad única" (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- 1 2 3 Martín Tabeira (2008). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Uruguayan Derby – Peñarol vs. Nacional". Retrieved 2007. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ ElObservador.com.uy (eds.). "El día que Nacional se retiró" (in Spanish). Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ↑ ovaciondigital.com.uy (23 April 2011). "Una fecha especial" (in Spanish). Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- 1 2 ElPais.com.uy, eds. (2 October 2011). "La hinchada de Peñarol se expresa en un documental" (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ↑ Flashes.com.uy, eds. (10 October 2011). "Manyas taquilleros" (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ↑ OvacionDigital.com.uy, eds. (20 October 2011). ""Manyas, la película" sigue imparable" (in Spanish). Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ↑ lr21.com.uy, eds. (21 October 2011). "30.000 mil personas vieron "Manyas"" (in Spanish). Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ↑ OvacionDigital.com.uy, eds. (12 April 2011). "Peñarol otra vez en la cima del mundo" (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 April 2011.

- ↑ Frank Ballesteros (2004). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Players in the Copa Libertadores". Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- ↑ IFFHS, ed. (2006). "Argentina – Uruguay 0:0 (0:0; 0:0)". Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- 1 2 Gwidon Naskrent; Roberto Di Maggio y José Luis Pierrend (2008). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "World Cup Champions Squads 1930–2006". Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- ↑ FIFA, ed. (2009). "Copa Mundial de la FIFA Brasil 1950". Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- ↑ Martín Tabeira (20 July 2010). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Uruguayan Squads in the World Cup". Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- 1 2 3 Morales, Franklin (1991). El libro de oro del centenario de Peñarol (in Spanish). Montevideo: Aguilar. p. 11.

- ↑ Longo, Ariel (2009). Campeones: tanta gloria olvidada (in Spanish). Montevideo.

- ↑ Mantrana Garlín. Por la verdad (in Spanish). Montevideo. p. 11.

- ↑ Pedulla, Carlos (21 November 2011). ultimasnoticias.com.uy, eds. "Damiani fue reelecto y el 2809 obtuvo tres cargos" (in Spanish). Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ↑ peñarol.org (eds.). "Autoridades" (in Spanish). Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ↑ ovaciondigital.com.uy, eds. (23 October 2012). "Carlos Sánchez es el nuevo gerente deportivo" (in Spanish). Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- 1 2 diariolarepublica.net, eds. (24 October 2011). "Alonso y Nieto: aumento de socios en Peñarol" (in Spanish). Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ↑ elobservador.com.uy, eds. (2 February 2012). "Morena cumple 60" (in Spanish). Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ↑ El Observador (ed.). "La última pelea de Nacional y Peñarol: ¿Quién tiene más campeonatos?" (in Spanish). Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- ↑ Edgardo de Léon; Walter Zunino (2008). IFFHS, ed. "Uruguay – 1905 season". Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- ↑ Edgardo de Léon; Walter Zunino (2008). IFFHS, ed. "Uruguay – 1901 season". Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- ↑ Edgardo de Léon; Walter Zunino (2008). IFFHS, ed. "Uruguay – 1903 season". Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- ↑ Edgardo de Léon; Walter Zunino (2008). IFFHS, ed. "Uruguay – 1907 season". Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- ↑ Edgardo de Léon; Walter Zunino (2008). IFFHS, ed. "Uruguay – 1908 season". Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- 1 2 Karel Stokkermans (2008). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Double Digits Domestical". Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- ↑ Karel Stokkermans (2007). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Unrelegated Teams". Retrieved 2007. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Karel Stokkermans (2009). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Unbeaten during a League Season". Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ↑ Francisco Fernández (2007). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Uruguay 2005/06". Retrieved 2007. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ ElReloj.com, eds. (29 March 2006). "Peñarol pierde 12 puntos en la tabla por sanción" (in Spanish). Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ↑ Karel Stokkermans (2009). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Unbeaten in the Domestic League". Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- 1 2 3 José Luis Pierrend (2004). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), eds. "Copa Libertadores Trivia". Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- 1 2 Karel Stokkermans (2009). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Club Records in Copa Libertadores". Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ↑ Osvaldo José Gorgazzi; José Luis Pierrend; Martín Tabeira (1999). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Supercopa 1969". Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ↑ Osvaldo José Gorgazzi (1999). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Honor Cup". Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ Osvaldo José Gorgazzi (2001). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Cup Tie Competition – First Division". Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ Osvaldo José Gorgazzi (2007). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation (RSSSF), ed. "Campeonato Rioplatense – Copa Dr. Ricardo C. Aldao (1913–1955)". Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ↑ Somnath Sengupta (8 March 2011). TheHardTackle.com, eds. "The Glorious History of IFA Shield". Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- 1 2 La Web Deportiva Uruguaya, ed. (2008). "Torneo de Invierno de Primera – Historial de campeones" (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- ↑ La República, eds. (24 February 2006). "Se larga Rutas de América con varios "candidatos"" (in Spanish). Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- ↑ Futsalplanet, ed. (2008). "Story – Uruguay" (in Spanish). Retrieved 2008. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - 1 2 BeachSoccer.com, eds. (2 January 2013). "Peñarol jumps to the beach!". Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ↑ Tenfield.com.uy, eds. (29 January 2013). "Fútbol playa: Peñarol ganó su grupo" (in Spanish). Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ↑ AUF.org.uy, eds. (7 February 2013). "Se suspendieron todos los partidos" (in Spanish). Retrieved 7 February 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to C.A. Peñarol. |

- Official website (in Spanish)

- C.A. Peñarol profile at FIFA.com