Charles Masterman

| The Right Honourable Charles Masterman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster | |

|

In office 11 February 1914 – 3 February 1915 | |

| Prime Minister | Herbert Henry Asquith |

| Preceded by | Charles Hobhouse |

| Succeeded by | Edwin Samuel Montagu |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 24 October 1873 |

| Died | 17 November 1927 (aged 54) |

| Alma mater | Christ's College, Cambridge |

Charles Frederick Gurney Masterman PC (24 October 1873 – 17 November 1927) was a radical Liberal Party politician, intellectual and man of letters, He worked closely with such Liberal leaders as David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill in designing social welfare projects, including the National Insurance Act of 1911. During the First World War, he played a central role in the main government propaganda agency.

Early life

He was distantly related to the Gurney family of Norfolk. His great-grandfather was William Brodie Gurney; his brother was Howard Masterman who became the Bishop of Plymouth.

Masterman was educated at Weymouth College, Christ's College, Cambridge, where he was President of the Union,[1] and joint Secretary of Cambridge University Liberal Club from 1895 to 1896.[2] He was elected a junior Fellow of Christ′s College in February 1900.[3] At university he had two primary interests: social reform (influenced by Christian Socialism) and literature. His first published work was From The Abyss, a collection of articles he had written anonymously whilst living in the slums of south east London. These were highly impressionistic pieces, and reflected his literary leanings. Following this he became involved in journalism and co-edited the English Review with Ford Madox Ford. In 1901, he edited a collection of essays by eminent people of the day, entitled The Heart of the Empire: a discussion of Problems of Modern City Life in England. A second edition of that book was published in 1907. In 1905 he published In Peril of Change, a collection of his own essays. He also wrote a biography of the Reverend F D Maurice (Frederick Denison Maurice), which was published in 1907. During the period of his life up to 1906, he established many of the literary friendships that would be important in his later role as head of British propaganda in the First World War.

Political career

He was an unsuccessful candidate at the Dulwich by-election, 1903, but in the Liberal Party landslide victory at the 1906, he was elected as Member of Parliament (MP) for West Ham North.

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal | Charles Frederick Gurney Masterman | 6,838 | 57.3 | +18.8 | |

| Conservative | Ernest Gray | 5,094 | 42.7 | -18.8 | |

| Majority | 1,744 | 14.6 | 37.6 | ||

| Turnout | 79.0 | +11.2 | |||

| Liberal gain from Conservative | Swing | +18.8 | |||

He married Lucy Blanche Lyttelton, a poet and writer, in 1908. In 1909, he published his best known book The Condition of England, a survey of contemporary society with particular focus on the state of the working class.

Masterman worked closely with Liberal leaders Winston Churchill and David Lloyd George on the People's Budget of 1909. By 1911, he was playing a major role in writing parts of the Finance Bill, the Development Bill, the Shop Hours Bill, and the Coal Mines Bill, and he was responsible for the passage through parliament of the National Insurance Act 1911.

He had a mediocre record as a candidate by losing more often than winning. He was re-elected in January 1910 and in December 1910, but the December election was later declared void.

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal | Charles Frederick Gurney Masterman | 6,657 | 53.6 | +02 | |

| Conservative | Ernest Edward Wild | 5,760 | 46.4 | -0.2 | |

| Majority | 897 | 7.2 | +0.4 | ||

| Turnout | 79.3 | -0.7 | |||

| Liberal hold | Swing | +0.2 | |||

He was returned to Parliament at a by-election in July 1911, for the Bethnal Green South West constituency.

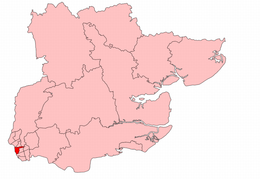

He joined the Privy Council in 1912, and in 1914, he obtained his most important position, an appointment to the Cabinet as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. However, the law at that time required him to recontest his seat in a by-election on joining the Cabinet. Masterman lost his own seat and then stood in a by-election at Ipswich, losing again. He resigned from the government as a result.[6]

Wartime propagandist

Masterman strongly supported entry into the First World War. He served as head of the British War Propaganda Bureau (WPB), known as "Wellington House."[7] His Bureau enlisted eminent writers (such as John Buchan, H. G. Wells and Arthur Conan Doyle) as well as painters such as Francis Dodd, Paul Nash. Until its abolition, in 1917, the department published 300 books and pamphlets in 21 languages, distributed over 4,000 propaganda photographs every week and circulated maps, cartoons and lantern slides to the media.[8]

He also commissioned films about the war such as The Battle of the Somme, which appeared in August 1916, while the battle was still in progress, as a morale-booster. It was generally received a favourable reception. The Times reported on 22 August 1916, "Crowded audiences ... were interested and thrilled to have the realities of war brought so vividly before them, and if women had sometimes to shut their eyes to escape for a moment from the tragedy of the toll of battle which the film presents, opinion seems to be general that it was wise that the people at home should have this glimpse of what our soldiers are doing and daring and suffering in Picardy".[9]

A major objective of his department was to encourage the United States to enter the war on the British and French side. Lecture tours and exhibitions of paintings were organised in the US, drawing on an extensive network of the most important and influential figures in the London arts scene, Masterman devised the most comprehensive arts patronage schemes ever to be supported in the country. It was subsumed into Buchan's Department of Information. It became a template for the war art scheme in the Second World War, headed by Sir Kenneth Clark.[10] Lloyd George demoted Masterman in February 1917; he now reported to Buchan. The agency was peremptorily closed as soon as the war ended, and neither Masterman nor Buchan received the usual public honorus. However, Masterman followed Lloyd George in his Liberal party maneuvers after 1918.[11]

Masterman played a crucial role in publicising reports of the Armenian Genocide, in part to strengthen the moral case against the Ottoman Empire. For his role, Masterman has been the target of repeated Turkish allegations that he fabricated, or at least embellished, the events for propaganda purposes.

Postwar

For the 1918 general election, Masterman returned to West Ham where he had sat for five years before the war. He contested the new seat of Stratford West Ham. However, his old boss, Lloyd George, chose to endorse his Unionist opponent, and he was badly beaten.

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unionist | Charles Ernest Leonard Lyle | 8,498 | 63.8 | n/a | |

| Liberal | Rt Hon. Charles Frederick Gurney Masterman | 4,821 | 36.2 | n/a | |

| Majority | 3,677 | 27.2 | n/a | ||

| Turnout | 13,319 | n/a | |||

| Unionist win | |||||

Later life

Back into private life, Masterman continued his high output of books and essays. In 1922, he published How England is Governed. In 1921, he supported the Manchester Liberals radical programme, adopted by the National Liberal Federation, which called for the establishment of a National Industrial Council, state supervision of trusts and combines, nationalisation of some monopolies as well as profit limitations.[13]

For the 1922 general Election, Masterman decided to contest Clay Cross in Derbyshire. At the previous election in 1918, the Liberal candidate had been endorsed by the Coalition Government and won. He subsequently took the Coalition Liberal whip and was defending his seat as a National Liberal, with the support of Lloyd George. The local Liberal association wanted an opponent of the coalition to run as their candidate and managed to attract Masterman. He outpolled the sitting member by nearly two to one, but the seat was won by the Labour candidate.

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labour | Charles Duncan | 13,206 | 57.9 | +12.0 | |

| Liberal | Rt Hon. Charles Frederick Gurney Masterman | 6,294 | 27.6 | n/a | |

| National Liberal | Thomas Tucker Broad | 3,294 | 14.5 | n/a | |

| Majority | 6,912 | 30.3 | 38.6 | ||

| Turnout | 22,794 | ||||

| Labour gain from Liberal | Swing | n/a | |||

After the election, there was discussion in Liberal circles, of Lloyd George and his National Liberals returning to the party. Masterman was concerned about such a move and talked about defecting to the Labour Party if that happened.[15] Masterman's good political relationship with the Manchester Liberals resulted in their inviting him to contest one of their constituencies, which he accepted. The Manchester Liberals won five seats at the 1923 general election, including Rusholme, where Masterman stood.

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal | Rt Hon. Charles Frederick Gurney Masterman | 10,901 | 43.4 | +17.3 | |

| Unionist | John Henry Thorpe | 8,876 | 35.3 | -12.6 | |

| Labour | William Paul | 5,366 | 21.3 | -4.7 | |

| Majority | 2,025 | 8.1 | +29.9 | ||

| Turnout | 78.0 | +0.2 | |||

| Liberal gain from Unionist | Swing | +15.0 | |||

Following his election victory in 1923, Masterman revealed to his wife Lucy that he "thought we were never going to (win) again".[16] In August 1924, he led opposition to a treaty, negotiated by the Labour government, which guaranteed a loan to the Soviet government.[17] During the 1924 election campaign, Masterman publicly blamed Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald for the collapse of Liberal-Labour co-operation.[18]

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unionist | Frank Boyd Merriman | 13,341 | 50.4 | +15.1 | |

| Liberal | Rt Hon. Charles Frederick Gurney Masterman | 7,772 | 29.4 | -14.0 | |

| Communist | William Paul | 5,328 | 20.2 | -1.1 | |

| Majority | 5,569 | 21.0 | 29.1 | ||

| Turnout | 79.8 | +1.8 | |||

| Unionist gain from Liberal | Swing | -14.5 | |||

In 1925, he became the Parliamentary Correspondent for The Nation. Having initially expressed concerns about Lloyd George's return to the Liberal Party, he had acknowledged that it was again easier to get the party to adopt measures of social reform: "When Lloyd George came back to the party, ideas came back to the party".[19]

Lloyd George sponsored a number of reviews into areas of Liberal Party policy, and Masterman participated in those reviews, notably as part of the body that produced the policy document 'Coal and Power'. He was also on the committee that ultimately produced 'Britain's Industrial Future', known as 'The Yellow Book'.[20]

Death

His health declined rapidly, hastened by drug and alcohol abuse. He died in November 1927. He was buried in St Giles' Church, Camberwell where a plaque commemorates him and other members of his family.

Legacy

Masterman had a long-standing influence as a champion of radical change. On one hand, he ridiculed anachronistic attachments to outmoded Victorian ideals and institutions. However, his own rhetoric was deeply rooted in high Victorian idealism. He proposed a wide-ranging program to assist the working class, such as labour exchanges, wage boards and free meals for schoolchildren. Historians have puzzled as to his ability to lose elections that had been prearranged for him. He had psychological problems, such as severe mood swings and mental health problems, and his public demeanour often struck observers as cynical and self-righteous.[21]

Lucy Masterman's biography of him was published in 1939.

The 2016 World War I video game Battlefield 1 has made references to Masterman through elaborate puzzles that are available in the game.

References

- ↑ "Masterman, Charles Frederick Gurney (MSTN892CF)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ↑ The Keynes Society: About us

- ↑ "University intelligence". The Times (36074). London. 24 February 1900. p. 13.

- ↑ British parliamentary election results, 1885-1918 (Craig)

- ↑ British parliamentary election results, 1885–1918, FWS Craig

- ↑ Matthew, "Masterman" (2015)

- ↑ "Espionage, propaganda and censorship". National Archives. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- ↑ D. G. Wright, "The Great War, Government Propaganda and English 'Men Of Letters' 1914-16." Literature and History 7 (1978): 70+.

- ↑ 'War's Realities on the Cinema', The Times, London, August 22, 1916, p 3

- ↑ Paul Gough, A Terrible Beauty: British Artists in the First World War (Sansom and Company, 2010) pp. 21–31

- ↑ Matthew (2015)

- ↑ British Parliamentary Election Results 1918-1949, FWS Craig

- ↑ The Downfall of the Liberal Party by Trevor Wilson

- ↑ The Liberal Year Book, 1927

- ↑ ,The Downfall of the Liberal Party, by Trevor Wilson

- ↑ The Downfall of the Liberal Party, by Trevor Wilson

- ↑ The Downfall of the Liberal Party, by Trevor Wilson

- ↑ Nation, 11 October 1924

- ↑ C.F.G. Masterman by Lucy Masterman, pages 345-6

- ↑ The Downfall of the Liberal Party, by Trevor Wilson

- ↑ Seth Kove, "Masterman, CFG" in Fred M. Leventhal, ed., Twentieth-century Britain: an encyclopedia (Garland, 1995) pp 502-3.

Further reading

- David, E. I. "Charles Masterman and the Swansea District By-Election, 1915." Welsh History Review= Cylchgrawn Hanes Cymru 5 (1970): 31+.

- Hopkins, Eric. Charles Masterman (1873-1927), politician and journalist: the splendid failure (Edwin Mellen Press, 1999).

- Mason, Francis M. "Charles Masterman and National Health Insurance." Albion 10#1 (1978): 54-75.

- Masterman, Lucy Blanche Lyttelton. CFG Masterman: a biography (1939); well researched account by his widow,

- Matthew, H. C. G. "Masterman, Charles Frederick Gurney (1873–1927)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2015 accessed 2 Aug 2016

External links

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Charles Masterman

- Tennyson as a Religious Teacher (1900)

- The Child and Religion article in collection edited by Thomas Stephens (1905)

- To colonise England: a plea for a policy edited with W B Hodgson and others (1907)

- Ruskin the Prophet article in collection edited by J H Whitehouse (1920)

- England after War: A study (1922)

- Full text of 'The Condition of England'

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Ernest Gray |

Member of Parliament for West Ham North 1906–1911 |

Succeeded by Baron Maurice Arnold de Forest |

| Preceded by Edward Hare Pickersgill |

Member of Parliament for Bethnal Green South West 1911–1914 |

Succeeded by Sir Mathew Richard Henry Wilson |

| Preceded by John Henry Thorpe |

Member of Parliament for Manchester Rusholme 1923–1924 |

Succeeded by Sir Frank Boyd Merriman |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Thomas James Macnamara |

Parliamentary Secretary to the Local Government Board 1908–1909 |

Succeeded by Herbert Lewis |

| Preceded by Herbert Samuel |

Under-Secretary of State for the Home Department 1909–1912 |

Succeeded by Ellis Ellis-Griffith |

| Preceded by Thomas McKinnon Wood |

Financial Secretary to the Treasury 1912–1914 |

Succeeded by Francis Dyke Acland |

| Preceded by Charles Edward Henry Hobhouse |

Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster 1914–1915 |

Succeeded by Edwin Samuel Montagu |