C.G. Conn

|

C.G. Conn Ltd. trademark on the exterior of a saxophone case dating from 1922 | |

| Private | |

| Founded | 1876 |

| Headquarters | Elkhart, Indiana, United States |

Key people | Charles Gerard Conn, founder |

| Products | Brass instruments |

| Parent | Conn-Selmer |

C.G. Conn Ltd., sometimes called Conn Instruments or commonly just Conn, was a United States manufacturer of musical instrument incorporated in 1915. It bought the production facilities owned by Charles Gerard Conn, a major figure in early manufacture of brasswinds and saxophones in the USA. Its early business was based mainly on such instruments, which it manufactured in Elkhart, Indiana. During the 1950s the bulk of its sales revenue shifted to electric organs. In 1969 the company was sold under bankruptcy to the Crowell-Collier-MacMillan publishing company. Conn was divested of its Elkhart production facilities in 1970, leaving remaining production in satellite facilities and contractor sources. The company was sold in 1980 then again in 1985, reorganized under the parent corporation United Musical Instruments (UMI) in 1986. The assets of UMI were bought by Steinway Musical Instruments in 2000 and in January 2003 were merged with other Steinway properties into a subsidiary called Conn-Selmer. C.G. Conn is currently a brand of musical instruments manufactured by Conn-Selmer.

History

Charles Gerard Conn

The company was founded by Charles Gerard Conn (b. Phelps, New York 29 January 1844; d. Los Angeles, California 5 January 1931). In 1850 he accompanied his family to Three Rivers, Michigan and in the following year to Elkhart, Indiana. Little is known about his early life, other than that he learned to play the cornet. With the outbreak of the American Civil War he enlisted in the army on 18 May 1861 at the age of seventeen, despite his parents' protests. On 14 June 1861 he became a private in Company B, 15th Regiment Indiana Infantry, and shortly afterwards was assigned to a regimental band. When his enlistment expired he returned to Elkhart, but re-enlisted on 12 December 1863 at Niles, Michigan in Company G, 1st Michigan Sharpshooters. At the age of nineteen on 8 August 1863 he was elevated to the rank of Captain. During the Assault on Petersburg on 30 July 1864, Conn was wounded and taken prisoner. In spite of two imaginative and valiant attempts to escape, he was recaptured and spent the remainder of the war in captivity. He was honorably discharged on 28 July 1865.

In 1884 Conn organized the 1st Regiment of Artillery in the Indiana Legion and became its first Colonel, a military title which stayed with him throughout the remainder of his life. He was also the first commander of the Elkhart Commandery of the Knights Templar. Colonel Conn also served as Lieutenant Colonel of the 2nd Regiment of Uniform Rank, Knights of Pythias, and was re-elected many times as Commander of the local G.A.R. post.

His home at Elkhart, the Charles Gerard Conn Mansion, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2007.[1]

Founding of Conn's band instrument manufactory

After the war, Conn returned to Elkhart and established a grocery and baking business. He also played cornet in the local community band. Conn's entrance into the musical instrument manufacturing business was the result of a split lip. There are three existing stories of how this occurred, but the popularly accepted version is that Del Crampton slugged him in the mouth outside a saloon where both of them had been drinking. Conn's upper lip was severely lacerated, and it pained him so to play his cornet that he thought his playing days were over. In addition to running his store, Conn also made rubber stamps and re-plated silverware. He decided to try adhering rubber stamp material to the rim of a mouthpiece which he hoped would conform to his lips. After he showed his friends his idea, he realized that there was tremendous demand for his invention. Conn then began to contemplate manufacturing his new mouthpiece. He needed a rim with a groove which the rubber cement would adhere to more easily. It was in 1874 when Conn converted a discarded sewing machine frame into a simple lathe and started to turn out his mouthpieces and was soon in full production (Subsequently, Conn and Del Crampton became best of friends, and when Conn embarked on his political career, he was a staunch advocate of temperance).

Conn patented his rubber-rimmed mouthpiece in 1875 (with patents to follow through 1877) described as "an elastic face [i.e., a rubber rim] where the mouthpiece comes in contact with the lips, the object being to prevent fatigue and injury to the lips." About this time Conn met Eugene Victor Baptiste Dupont (b. Paris ?May 1832; d. Washington, D.C. 26 July 1881), a brass instrument maker and designer and a former employee of Henry Distin of London. In January 1876, Conn joined with Dupont under the name of Conn & Dupont, and Dupont created Conn's first instrument, the Four-in-One cornet, with crooks allowing the horn to be played in the keys of E♭, C, B♭, and A. By 1877, Conn's business had outgrown the back of his grocery store, and he purchased an idle factory building on the corner of Elkhart Avenue and East Jackson. Conn's partnership with Dupont was dissolved by March 1879, but he was successful in attracting skilled craftsmen from Europe to his factory, and in this manner he expanded his operation so that by 1905, Conn had the world's largest musical instrument factory producing a full line of wind instruments, strings, percussion, and a portable organ. Conn partnered with Albert T. Armstrong, Joseph Jones, and Emory Foster to manufacture a twin-horn disc phonograph called the 'Double-Bell Wonder' that was produced in two iterations briefly in early 1898 before a lawsuit by the Berliner Gramophone Company caused production to cease. Brick-red 'Wonder' records were also pressed for the 'Double-Bell Wonder' talking machine by the Scranton Button Works from pirated Berliner masters. Fewer than fifty 'Double-Bell Wonders' were produced of both iterations combined.

Conn's first factory was destroyed by fire 29 January 1883 (his thirty-ninth birthday), and he erected a new building on the same site. In 1886 rumors began to circulate that Conn wanted to move his business to Massachusetts. Conn was induced to stay after the public raised a large sum of money by popular subscription and gave it to him. In 1887 Conn purchased Isaac Fiske's brass instrument manufactory (upon Fiske's retirement) in Worcester, Massachusetts. Fiske's operation was considered to be the best in its time. Conn operated it as a company subsidiary, and in this way he achieved his objectives. The company's product line now centered around the 'Wonder' cornet, but in 1885 Conn began importing French clarinets and flutes. Conn started production of the first American-made saxophone in 1888, after being shown an Adolphe Sax saxophone by his employee Ferdinand August Buescher and agreeing to produce copies of it. That instrument belonged to E.A. Lefebvre, a well known soloist with both Patrick Gilmore's and John Philip Sousa's bands. Conn's instruments were endorsed by several leading band directors, including Sousa. In 1898, upon the suggestion of Sousa, Conn developed the first commercially successful bell-up sousaphone ("the rain-catcher"). Conn phased out the Worcester operation (production was ceased in 1898), and Conn established a store in New York City (1897–1902) which a large variety of merchandise was sold under the 'Wonder' label, which included Conn-made woodwind, brass and percussion instruments, violins, mandolins and portable reed organs. The business also distributed American-made and imported guitars, banjos and zithers.

Conn's company was a source of competitors as well as instruments. Notable employees who left the firm to pursue their own businesses were composer W. Paris Chambers, the founder of the Seidel Band Instrument Company William F. Seidel, the founder of the Buescher Band Instrument Company Ferdinand A. Buescher, the founder of the F.E. Olds Company Frank E. Olds, and the founder of the Martin Band Instrument Company Henry Charles Martin.

Conn's second factory burned on 22 May 1910, a loss estimated between $100,000 and $500,000. Conn was en route from California to Elkhart when his factory burned, and upon arriving home he was met with a public demonstration, a way of showing popular sympathy. Conn then announced his intentions to build a third factory on the corner of East Beardsley and Conn Avenues. Construction began 15 August 1910, and by the following 12 December it was fully operational.

Conn's other enterprises

Colonel Conn was a colorful personality of the show biz sort. He believed that he could do anything. His career grew far beyond the confines of horn making. In 1880 Conn was elected Mayor of Elkhart on the Democratic ticket. He was re-elected in 1882 but did not finish the term. Ten days before the general election in 1888, Conn was drafted as an emergency candidate for the Indiana House of Representatives by the Democrats, and won the election. In 1892 he was elected to the United States Congress as Representative of the 13th District of Indiana. Two years later he was re-nominated, but declined the nomination unless the party permitted him to make the canvass on a "reformed" platform. The party would not permit this, and accepted his declination. In 1908 he ran for Governor of Indiana and lost; in 1910 he ran for Senator. Conn's term in the House was one that provided help for Civil War veterans seeking assistance.

Colonel Conn also had a love affair with publishing. He founded a newspaper, the Elkhart Daily Truth, on 15 October 1889. The paper still exists as the The Elkhart Truth. He published the monthly Trumpet Notes which he circulated amongst his employees and dealers. He also published a scandal sheet called The Gossip which, along with the town doings, he used occasionally to attack his competitors and enemies. While a member of Congress he purchased the Washington Times. He conducted a sensational campaign against alleged vice in the city. Eventually he found himself as a defendant in a big damage suit, but won the case. Sometime later he disposed of the paper.

Colonel Conn had heavily invested money in other businesses. One of his disappointments was his involvement with early electrical generating systems. In 1904 he constructed a powerhouse and provided electrical service as a competitor to the Indiana and Michigan Electric Company. They later bought out Conn's service at a great sacrifice to himself. The turning point to Conn's financial affairs and public life took place in April 1911 when he and his wife executed a trust deed for $200,000 covering all their possessions for the purposes of bonding the Conn indebtedness and securing working capital, the longest bond to mature in ten years. Conn's money problems stemmed partly from failed ventures like his entry into the utilities business, the building of his third factory, and its loss to fire, and his loss of a costly lawsuit filed against him by a former company manager. The deed included in addition to the horn factory and what was then known as the Angledile Scale Company, and The Elkhart Truth, some sixty descriptions of real estate in Elkhart and vicinity, various real estate mortgages, 125 shares of stock in the Simplex Motor Car Company of Mishawaka, Indiana, a seagoing yacht, a lake motor launch, and much valuable personal property. Conn also lost considerable face when he was ordered by a judge to publicly apologize for publishing inflammatory comments about J. W. Pepper. The Musical Courier picked up on the legal problems and reported about how Conn was knowingly making false statements about Pepper. In his published apology, Conn attributed his aberrant behavior on an addiction to tobacco.

In 1915 Conn's growing debt crisis forced him to seek a buyer for his assets. All of Colonel Conn's holdings were bought by a group of investors led by Carl Dimond Greenleaf (b. Wauseon, Ohio 27 July 1876; d. Elkhart, Indiana 10 July 1959). Conn met Greenleaf during his years in Washington, D.C., and invested in some grain mills in Ohio which Greenleaf owned. Initially Conn held onto ownership of The Elkhart Truth, but a few months after the sale of his other holdings, Conn sold The Elkhart Truth to Greenleaf and to a local entrepreneur Andrew Hubble Beardsley. The sale was detrimental to Colonel Conn's marriage. They divorced, and Mrs. Conn was allowed to retain a house in Elkhart in which she lived until her death in 1924. Colonel Conn meanwhile was allowed to keep his home in Los Angeles, California. He spent virtually the remainder of his life there and only returned to Elkhart once in 1926 to visit his sister. He remarried to a very young woman while in California, and they had a son twelve years before Conn's death in 1931. Once a very wealthy and influential man, he died almost penniless. His estate didn't have enough money in it to afford a grave marker, and a hat was passed around the horn factory to collect enough money to buy one.

Carl D. Greenleaf and C.G. Conn, Ltd., 1915-1949

Carl Greenleaf was president of Conn from 1915 to 1949. Greenleaf incorporated his new holdings under the name C.G. Conn Ltd., a company with public stock offerings, and retained the Conn trademark on his musical instruments. He was an astute businessman, very sensitive to the market trends of the industry. While president, Greenleaf was noting the gradual extinction of the small town brass band, and of the big touring bands such as the Sousa band. He knew that in order for the industry to survive, band programs had to be promoted in schools and colleges. He proceeded to develop a close relationship and communications between the industry and music educators. His collaboration with educators such as Joseph E. Maddy and T.P. Giddings helped introduce band music into the schools. Greenleaf organized the first national band contest in 1923 and helped make possible the founding of the National Music Camp at Interlochen, Michigan. In 1928 he founded a Conn National School of Music which trained hundreds of school band directors, and this in turn helped spur the development of music programs in schools and communities across the United States.

Greenleaf expanded, upgraded and retooled the Conn plant, and converted the company from a mail-order business to one operated through retail dealers. By 1917 the assembly-line work force had increased to 550 employees who were turning out about 2500 instruments a month using a new hydraulic expansion process which Greenleaf introduced to the plant. In 1917 Conn introduced the Pan American brand for its second-line instruments. Conn founded the subsidiary Pan American Band Instrument Company in 1919 and later that year moved production of second-line instruments to the old Angledile factory. By 1930 the Pan American company was fully absorbed by Conn, but the Pan American brand for Conn's second-line instruments remained in use until 1955. By 1920 Conn was producing a complete line of saxophones. In this area they had stiff competition from other big saxophone makers such as Buescher and Martin. Around 1917 Conn introduced drawn tone holes (after a patent by W.S. Haynes in 1914) eliminating the necessity of soft-soldering tone hole platforms onto the bodies of the instruments. Around 1920 Conn introduced rolled tone hole rims, a feature that enhanced the seal of the pads and extended pad life. Rolled tone holes remained a feature of Conn saxophones until 1947.

Conn founded the Continental Music retail distribution subsidiary in 1923. At its height, the operation included a chain of over 30 music stores.

During the 1920s Conn owned the Elkhart Band Instrument Company (1923–27), the Leedy Company (1927–55), a manufacturer of percussion, and 49.9% of the stock of the retailer H. & A. Selmer (1923–27). Despite the stock market crash of 1929, Conn purchased several companies (1929–30) including Ludwig and Ludwig, a maker of percussion, and Carl Fischer and Soprani, makers of accordions. From 1940 to 1950 they owned the Haddorff Piano Company, and from 1941 to 1942 the Straube Piano Company.

By the late 1920s the success of Conn's latest "New Wonder" model saxophones with dance orchestras was gaining widespread attention, leading European manufacturers to produce horns closer to the deeper, richer, bolder "American" sound. Selmer (Paris) introduced the American-sounding "New Largebore" model in 1929 and the new Julius Keilwerth Company in Czechoslovakia produced saxophones influenced by the Conn design, including rolled tone holes and microtuners.

In 1928, as sax sales plateaued, Conn attempted to introduce a mezzo-soprano saxophone in the key of F and the 'Conn-o-sax', a saxophone-English horn hybrid, to capture more of the market, but these instruments were soon discontinued after disappointing sales.

In 1928 Conn opened its Experimental Laboratory, which was unique in the industry, under the direction of C.D.'s son Leland Burleigh Greenleaf (Wauseon, Ohio, 12 August 1904 – Leland, Michigan, 29 March 1978). Under his directorship, the department developed the first short-action piston valves (1934), and the 'Stroboconn' (1936), the first electronic visual tuning device. It also developed the "Vocabell" (1932), a bell with no rim to optimise the sound, and the "Coprion" bell (1934), a seamless copper bell formed by directly electroplating it onto a mandrel. Under Lee Greenleaf and his saxophone specialists Allen Loomis and Hugh Loney, Conn's research and development process resulted in the basic designs of the 6M alto (1931–69), 10M tenor (1934–69), and 12M baritone (1929–69), which were incrementally modified after 1946 to save manufacturing costs. From 1935 through 1943, Conn produced the 26M and 30M "Connqueror" alto and tenor saxophones, featuring screw-adjustable keywork and improved mechanisms for the left hand cluster. The keywork was the most fully adjustable of any saxophone during that period. Conn's laboratory was expanded into the Division of Research, Development and Design in 1940, directed by Earle Kent (b Adrian, Texas 22 May 1910; d Elkhart 12 January 1994). They developed the "Connsonata" organ, the first electronic (as opposed to tonewheel electric) organ in 1946, improved electronic tuners, and various other electronic musical devices during the postwar era. Conn's combined abilities in close-tolerance manufacturing and electronic devices made them a valuable resource for wartime contracts.

From mid-1942 to 1945, Conn ceased all production of musical instruments for civilian use to manufacture compasses, altimeters, and other military instrumentation. Production was interrupted again by a strike in 1946-47. The loss in sales from those disruptions and increased competition from other manufacturers such as Selmer (Paris) and King (H. N. White) caused a serious decline in Conn's status as a major band instrument manufacturer. Conn responded by developing more electronic musical products and the "Connstellation" model wind instruments to revitalize those product lines (28M alto saxophone with help from Santy Runyon, 1948, and brass instruments, mid-1950s). The Connstellation brasswinds remained a premium line through the 1960s.

The Paul Gazlay - Lee Greenleaf era, 1949-1969

Carl Greenleaf retired in 1949 but remained a member of the board of directors until his death in 1959. He was succeeded by Paul Gazlay. Conn briefly returned to manufacture of military instrumentation during the Korean War, while continuing production of musical instruments. Priorities changed under Gazlay, with the high quality wind instruments on which the company had built its reputation becoming an increasingly marginal interest. The 28M saxophone was discontinued after 1952 and cost-cutting measures were incorporated into the manufacturing process and designs of its 6M, 10M, and 12M "Artist" series saxophones. Conn shifted their emphasis to the expanding market for school band instruments and to diversifying their instrument lines. In 1956, Conn sponsored a film to promote school bands entitled Mr. B Natural. To diversify their product line, Conn acquired as subsidiaries the New Berlin Instrument Company (1954–1961) of New Berlin, New York which produced clarinets, oboes and bassoons for Conn, the Artley Company (1959), a manufacturer of flutes and clarinets, the Janssen Piano Company (1964), and the Scherl & Roth Company (1964), a manufacturer of stringed instruments. Conn divested itself of Leedy and Ludwig in 1955 and New Berlin Instrument in 1961. By 1958, over half of Conn's sales revenue was from their electric organs. In 1959 Conn built a new organ factory in Madison, Indiana. The Janssen Piano assets were merged with Conn's organ division to form Conn Keyboards in 1964. In 1958, Lee Greenleaf succeeded Gazlay as company President.

In 1960, Conn acquired the Art Best Manufacturing Company (Coin Art) facility that manufactured saxophones in Nogales, Arizona. They continued manufacturing saxophones of the Vito design that were produced there, marketed as the Conn 50M and 60M alto and tenor saxophones, then moved the production of their 14M and 16M student alto and tenor saxophones to the facility in 1963. Production of other wind instruments remained in Elkhart.

The late 1960s saw trends in the keyboard, wind, and stringed instrument markets that were seriously undermining Conn's position. The growing popularity of portable electronic keyboards was cutting into Conn's niche of home organs and pianos. The market for student instruments was becoming increasingly competitive, with aggressive newcomers from Japan offering products more efficiently produced with high quality standards, and tailored to students' needs. Conn saxophones had ceased to be competitive in the professional market during the 1950s due to outdated designs and declining quality. By the late 1960s, their student line instruments were in competitive decline for similar reasons. By 1969, C. G. Conn, Ltd. was facing insolvency.

Company from 1969 to 2003

In 1969 C.G. Conn Ltd. was sold under bankruptcy to the Crowell-Collier MacMillan Company. Under their ownership the company's prestige declined further, because of mis-steps by company executives who were not familiar with instrument manufacturing that further decreased quality and service. In 1970, the corporate offices were moved to Oak Brook, Illinois, Conn Keyboards was moved to Carol Stream, Illinois and their piano manufacturing operation sold. Also in 1970, Conn's Elkhart manufacturing facilities were sold to Selmer (USA) and Coachmen Industries. Brasswind manufacturing moved to Abilene Texas and woodwind production was moved from Nogales, Arizona to Nogales, Mexico. Whatever was left of Conn's reputation for wind instruments was effectively finished as a result of those moves. Conn introduced the modernized 7M alto saxophone; it soon acquired the same reputation for poor quality as the other "MexiConns," sold poorly, and was discontinued. Student line brasswind manufacturing was outsourced to Yamaha in Japan. In 1970 Conn also started the Conn Guitar Division, operating out of Oak Brook, Illinois, contracting the manufacture of a new line of acoustic guitars to Tokai Gakki in Japan. Conn's acoustic guitar business ended in 1978. In 1979 Conn tried to enter the highly competitive electric guitar market, introducing a line of some original model electric guitars, and some copies of existing popular brands. (see History of Conn Guitars).

In 1980 the company was sold to Daniel Henkin (b. 18 March, 1930, Kansas City, Missouri, d. Elkhart, Indiana, 8 November, 2012) who had served the company as an advertising manager during the 1960s. Henkin moved the corporate offices back to Elkhart and moved to re-focus the company on wind instruments. First to go were the failing electric guitar venture, which was discontinued, and Conn Keyboards, sold to Kimball. Henkin hired Tonight Show trumpeter and bandleader Doc Severinsen as Vice President of Product Development and introduced the Conn Severinsen[2] trumpet and Henkin student clarinet. In 1981 he bought the W.T. Armstrong Company, a manufacturer of flutes and marketer of H. Couf branded saxophones made by the Julius Keilwerth company of West Germany. After that acquisition the Keilwerth instruments were also sold as "Conn DJH Modified" models. The company introduced a student line of oboes and bassoons under the Artley brand in 1983. Also in 1983, Henkin acquired King Musical Instruments of Eastlake, Ohio from the defunct Seeburg Corporation's creditors. In 1985 the Conn Strobotuner division was bought by Peterson Electro-Musical Products, who continue to service their line of products.[3] In 1985, Henkin was seeking a buyer for his companies.

The Swedish venture capital firm Skåne Gripen bought King and C.G. Conn, from Henkin in 1985. The two companies were merged to create a new parent corporation, United Musical Instruments headquartered in Nogales, Arizona. UMI subsequently closed the Conn Brasswind facility in Abilene, Texas (1986), moving brass instrument production to the King plant in Eastlake. All operations were moved out of Mexico in 1987. Production of Artley flutes was moved to the W. T. Armstrong facility in Elkhart and reed instrument production was moved back from Nogales, Mexico to Nogales, Arizona.

In 1990 UMI was sold to Bernhard Muskantor, one of the Skåne Gripen partners. Muskantor, with family roots in the musical instrument business, desired a return of the Conn name to respectability but its top line of saxophones was lost when Keilwerth went independent with their marketing in 1989 and the increasingly tough market with new low-cost Asian competitors kept Conn's position marginal.[4] In 2000 UMI was purchased by Steinway Musical Instruments, and in January 2003 the UMI assets were merged with The Selmer Company to create Conn-Selmer, a subsidiary of Steinway Musical Instruments.

Conn Res-o-Pads

Between 1920 and 1947, all professional-grade saxophones manufactured by C.G. Conn had rolled toneholes. In the early 1930s, Conn developed a unique type of saxophone pad called "Conn Res-o-Pads", which were specifically designed for use on saxophones with rolled toneholes.[5][6] Conn Res-O-Pads have an internal metal reinforcing ring which is hidden under the leather covering around the circumference of the pad. Their most notable feature is that the diameter of the pad extends over the rim of the key-cup, thereby giving a slightly wider surface area for the rolled tone-hole to seal onto. Rim impressions from Res-o-Pads are minimal and unlike standard pads they cannot be "floated" in. Though designed to fix into key-cups purely via friction, most saxophone repairers glue them in place using shellac or hot melt adhesive. Res-o-Pads can be challenging to size correctly because (unlike standard saxophone pads which come in 0.5 mm size steps) they are only available in 1/32nds of an inch sizes which may not always correspond closely to key-cup diameters. Newly produced Conn Res-o-Pads are still available from specialist suppliers and are favored by some saxophone collectors because they give a fully authentic look and feel to vintage saxophones with rolled toneholes e.g. those made by Conn, Kohlert and Keilwerth. However, it is possible to fit standard pads to any saxophone with rolled toneholes (and many people do) without any noticeable disadvantage regarding the quality of sound produced.[7]

The Conn Microtuner

From 1922 to 1950 Conn manufactured alto and c-melody saxophones with a unique tuning device on the neck (adjacent to the mouthpiece) known as the "Conn Microtuner." The feature was devised to allow the saxophone to be tuned while maintaining optimal volume in the chamber of the mouthpiece, thus avoiding disturbance to intonation. Instead of adjusting the tuning of the instrument in the traditional way (moving the mouthpiece up and down the cork), Conn introduced a fixed mouthpipe, controlled by a threaded barrel which increased or decreased the length of the neck internally.[8] To lower the pitch, the barrel was rotated to the left. To raise the pitch the barrel was rotated to the right. The design of the microtuner was changed slightly in the mid-1930s, and some necks were stamped "viii" to mark compatibility with one or another series of barrels while both types were in production. The value of microtuners has been controversial among musicians because the internal mechanism required extra cleaning and maintenance, and was a potential source of leaks. The benefits of the microtuner to intonation have been shown to be more theoretical than practical. Some repair technicians who have play-tested large numbers of Conn altos (cf. Les Arbuckle of Saxoasis.com) report that the microtuner necks lend a different sound quality from those without one. Keilwerth and other German-made saxes also used microtuners for a time. Since the 1950s, all new saxophones use the traditional tuning method i.e. pulling out or pushing in the mouthpiece on the cork until the pitch is correct.

Gallery

- A "Transitional" Conn New Wonder 'Series II' tenor saxophone made in 1934

- Conn 6M "Lady Face"[9] (dated 1935) in its original case

- Left side view of Conn 6M "Lady Face" alto saxophone showing distinctive underslung octave key

- Right side view of Conn 6M "Lady Face" alto saxophone

- Close-up view of neck with underslung octave key mechanism (no microtuner) on a Conn 6M "Lady Face" alto saxophone

- Detail of Conn 6M alto saxophone (dated 1935) showing distinctive pre-1947 rolled saxophone tone holes. Note that Conn Res-o-Pads have not been fitted

- A straight-necked Conn C melody saxophone (New Wonder Series 1)[10] dated 1922. The neck has a Conn micro-tuner on the end.

A straight-necked Conn C-melody saxophone (New Wonder Series 2 dating from circa 1926) played by Nathan Haines

A straight-necked Conn C-melody saxophone (New Wonder Series 2 dating from circa 1926) played by Nathan Haines- A Conn 'Pan American' alto saxophone, manufactured circa 1948. Has a similar body to a Conn 6M and keywork which is reminiscent of a Conn New Wonder Series 1 and 2

.jpg) Johnny Hodges in 1946, playing a Conn 6M alto sax

Johnny Hodges in 1946, playing a Conn 6M alto sax Charlie Parker in 1947, playing a Conn 6M alto saxophone

Charlie Parker in 1947, playing a Conn 6M alto saxophone

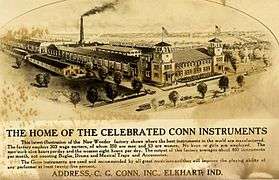

1911 Brochure Cover Illustration

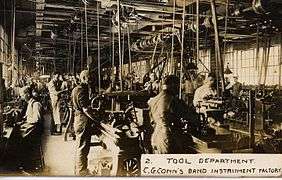

1911 Brochure Cover Illustration Tool department

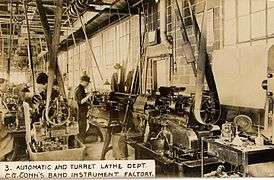

Tool department Automatic and turret lathe department

Automatic and turret lathe department Power Press

Power Press Mouthpiece making department

Mouthpiece making department Valve making department

Valve making department Bell and branch department

Bell and branch department Draw bench department

Draw bench department Cornet and trumpet mounting department

Cornet and trumpet mounting department Crook making department

Crook making department Helicon bending department

Helicon bending department Bending department

Bending department Trombone department

Trombone department Brass instrument repair department

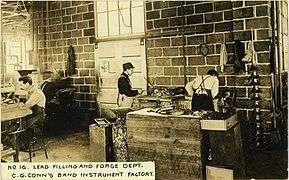

Brass instrument repair department Lead filling and forge department

Lead filling and forge department Saxophone department

Saxophone department Buffing department

Buffing department Strapping department

Strapping department Plating department

Plating department Engraving and burnishing department

Engraving and burnishing department Brass instrument assembling department

Brass instrument assembling department Brass foundry

Brass foundry Electric power room

Electric power room Heating plant blast fans

Heating plant blast fans Boiler room

Boiler room Wood working machine department

Wood working machine department Wood bending department

Wood bending department Case making department

Case making department String instrument department

String instrument department Flute and Piccolo makers and clarinet assembling department

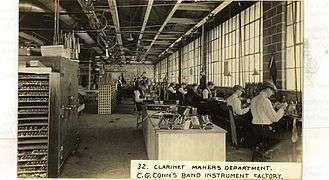

Flute and Piccolo makers and clarinet assembling department Clarinet makers department

Clarinet makers department Read instrument body making department

Read instrument body making department Drum making department

Drum making department Read instrument testing department

Read instrument testing department Cornet and trumpet testing department

Cornet and trumpet testing department Packing and receiving department

Packing and receiving department Accounting department

Accounting department Stenographic department

Stenographic department Operating room photo department

Operating room photo department Printing room, photo department

Printing room, photo department Dictation room number one

Dictation room number one Dictation room number two

Dictation room number two C.G.Conn's Private Office

C.G.Conn's Private Office

See also

- Buescher Band Instrument Company

- Martin Band Instrument Company

- Peterson Electro-Musical Products

- York Band Instrument Company

References

- ↑ National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ Previous Severinsen trumpets were produced by Getzen

- ↑ "Tuning History". Peterson Tuners. Retrieved 2011-05-10.

- ↑ Bernhard Muskantor on the future of United Musical Instruments,The Music Trades, June 1990

- ↑ Saxophone questions from our friends & clients . . . CyberSax Tech Topics . . . Vintage & Pro Saxophones

- ↑ MusicMedic.com: Measuring for Conn Res-O-Pads

- ↑ Conn 6M "Underslung" alto sax review

- ↑ Servicing the Conn Microtuner

- ↑ http://www.saxpics.com/?v=gal&c=534

- ↑ http://www.saxpics.com/?v=gal&c=622

- New Grove Music Dictionary ("Conn")

- McMakin, Dean "Musical Instrument Manufacturing in Elkhart, Indiana" (unpublished typescript, 1987, available at Elkhart Public Library)

- The Elkhart Truth, Tuesday 6 January 1931, obituary for C.G. Conn, and subsequent notices published 7 Jan., 8 Jan., 9 Jan., 14 Jan., 15 Jan.

- "About Conn-Selmer, Inc." on Conn-Selmer web site

- Elkhart city directories (available at Elkhart Public Library)

- Reed, Charles Vandeveer, "A History of Band Instrument Manufacturing in Elkhart, Indiana," unpublished MS Thesis, Butler University, 1953, 90p.

External links

- Conn-Selmer

- A Brief History of the Conn Company (1874-present), Margaret Downie Banks, Ph.D., Senior Curator of Musical Instruments, National Music Museum, Vermillion, South Dakota

- 1905 Magazine Article with photos

- The Conn Loyalist - About Conn Brass Instruments from the days when the C.G. Conn company was still located in Elkhart, Indiana

- Review of a Conn 6M Alto Saxophone manufactured in 1944

- The C.G. Conn 'Double-Bell Wonder' disc phonograph of 1898

- Straube factory in 1922, courtesy of the Indiana Historical Society

- Straube player pianos in 1922, courtesy of the Indiana Historical Society