Charles Cheffins

Charles Frederick Cheffins (10 September 1807 – 23 October 1861[1]) was a British mechanical draughtsman, cartographer, and consulting engineer, assistant to John Ericsson and George Stephenson and surveyor on many British railroad companies mid 19th century. He is also known from the 1850 Cheffins's Map of English & Scotch Railways and other maps.

Biography

Charles Frederick Cheffins was born in London on 10 September 1807. His father had for many years acted as official manager to the New River Waterworks Company, in superintending the boring by machinery of the wooden pipes then in use for the supply of water to the metropolis. Having been so fortunate as to obtain a presentation to Christ's Hospital, young Cheffins was, in July 1815, admitted as a scholar into that institution, where he remained till the year 1822, prosecuting his studies with a fair amount of diligence, and obtaining several gold medals for his proficiency in arithmetic and mathematics.[2]

On the completion of his education, he started working at Messrs. Newton and Son, patent agents and mechanical draughtsmen. In their employ he obtained some excellent practice, in making drawings from specifications and from models of machinery, which proved very useful to him in his after-career, and aided in giving him that intimate knowledge of his profession which he was admitted to possess. With Messrs. Newton and Son he remained some time after the expiration of his pupilage.[2]

From 1830 he obtained an engagement, under Captain John Ericsson, to assist in making the drawings for the locomotive engines. The next year he became assistant to George Stephenson, and worked in the preparation of the plans and sections of the projected Grand Junction Railway.[3] On the completion of the Grand Junction Railway, he set up his own cartographical and drawing business[4] and spend over two decades working as surveyor for numerous railroad construction projects in the United Kingdom. In 1838 he published his first Map of the Grand Junction Railway and Adjacent Country; and the next year Cheffins's Official Map of the Railway from London to Birmingham, Manchester and Liverpool under sanction of the directors.[5] In 1846 Cheffins commissioned John Cooke Bourne to produce his History of the Great Western Railway.[6] Occasionally Cheffins also published lithographical work by others. In the year 1848 he had been elected an Associate of the Institution of Civil Engineers, and he never ceased to take great interest in all the proceedings.[2]

One year before for his death in 1861 the partnership of Charles Frederick Cheffins and his sons, Charles Richard Cheffins, and George Alexander Cheffins, as surveyors, draftsmen, and lithographers, at No. 11, Southampton-buildings, and No. 6, Castle-street, Holborn, London, had been dissolved by mutual consent. The business continued with Charles Frederick Cheffins and Charles Richard Cheffins as continuing partners.[7] Cheffins died from an internal injury on 23 October 1861,[8] after only a few hours’ illness, leaving his son (with whom he had been associated in partnership for some years) to complete that which he had with so much zeal only a month, or two, previously commenced. His death, at the early age of fifty-four years, caused profound regret to all those with whom he had been connected for so many years, as also to those of his assistants, who had served under him in the numerous parliamentary campaigns in which he had been engaged - and to many of whom he had shown much kindness in recommending them to posts of trust and responsibility on the Indian railways.[2]

Work

Locomotive design

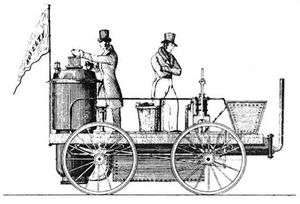

About the year 1830, he obtained an engagement, under Captain John Ericsson, to assist in making the drawings for the Novelty locomotive engine, then about to be constructed by Messrs. Braithwaite and Ericsson, for competition with the Stephenson's Rocket and other engines on the Rainhill Trials on the Manchester and Liverpool Railway.

The result of the competition, as is well known, proved adverse to the Novelty, on account of the failure of the blast apparatus. Cheffins was present at the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, and remained some time longer with Captain Ericsson, making drawings for other inventions, amongst which was a steam fire-engine and a caloric engine - machines which excited considerable attention at the period, and the former of which has since come into general use. In these matters Cheffins’ practical knowledge of machinery rendered him a very valuable assistant in the preparation of the designs.[2]

Testimony in patent right lawsuit

In 1830 Cheffins testified in a case of Lord Galloway and Alexander Cochrane versus John Braithwaite and John Ericsson.[9] Cheffins gave the following testimony:

- Mr. Charles Frederick Cheffins, mechanical draughtsman, saith, that on 27 July 1830, he went to the manufactory of Mr. Galloway, and saw the boiler exhibited by him in operation. There was no vessel containing a column of water attached to said boiler, but that, on the contrary, there was a considerable quantity of smoke issuing out from the upper extremity of the upright open pipe or chimney (Y). He asked Mr. Galloway, jun., where said column of water was placed, so as to afford resistance to the passage of the heated air? That Mr. Galloway, jun. told him they did not use a column of water to this boiler, but that in order to obtain a resistance they had diminished the area of the upright open pipe or chimney, so that its area should be less than the area of the flue in the boiler (but which area, to the best of the deponent's judgment, was more than thirty square inches; that is to say, the pipe measured five Inches by eight), thereby effecting the desir d object. That deponent farther observed, that the ante-chamber or magazine through which the furnace was supplied with fuel was not surrounded by water, as represented in the plaintiffs' specification and drawing. That the deponent considers that the plaintiffs have been enabled to dispense with such contrivance, from the reason that the heated air, instead of being subjected to a considerable pressure at the end of the flues, is suffered to escape freely into the atmosphere through an open pipe or chimney, whose sectional area, to the best of deponent's belief, measures five inches by eight inches. That upon asking Mr. Galloway, jun. how long said boiler had been in operation, he was answered, that it had been in constant work for seven months. That a boiler was shown to deponent constructed with a vessel to contain water, and an upright tube similar to drawing in plaintiffs' specification, but which deponent was informed had only been used for experiments, and that the said boiler was not in operation at the time deponent saw it.[10]

The Lord Chancellor responded "... with respect to that case of Cochrane and Braithwaite, correct me if I am wrong with respect to those affidavits handed in, which I was to look at, respecting the patent for steam-engines;. I do not find that Mr. Galloway carries back the use of the boiler beyond six months... Now the patent of Mr. Braithwaite is one year and a half old, and it is dated in January, 1829; so that this boiler which Mr. Galloway is now showing was, in point of fact, not in use till one year after Mr. Braithwaite's patent was obtained. Under these circumstances, I think the parties ought to be left to try their right at law, and the injunction to be dissolved. It is quite unnecessary for me, in this stale of things, to give any opinion with respect to the patent; but this much, however, I will state, I have read the specification with attention, and the evidence, and it appears to me that the objects of the two patents are different..." [10]

Cheffins take the stand in court more often. In one 1847 case narrated in The Railway Record, Charles F. Cheffins, engineer and surveyor, was called for the defence, and proved that he had examined the plans and sections in question, and detected so many errors, that the case became quite clear.[11]

Grand Junction Railway

In 1831 he was introduced to George Stephenson, by the Mr. Padley, who was that gentleman's oldest associate and surveyor. After the successful opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, numerous other schemes were immediately started, in which the great Engineer occupied a prominent position.

Cheffins’ first occupation under Mr. Stephenson was in the preparation of the plans and sections of the projected Grand Junction Railway, which had for its object the connection of the towns of Birmingham and Liverpool ; and it was whilst engaged upon this work, that his persevering industry was noticed by those with whom he was brought into contact ; amongst whom may be mentioned Joseph Locke, Frederick Swanwick, Daniel Gooch, and many others, who have since become eminent in the Engineering profession.[2]

Lithograph of London Station

In 1830 Cheffins started making lithographs, which were published in magazines such as in the 1837 The Mirror. The prefixed engraving represents the London Terminus of the London and Birmingham Railway, at Button Grove, near Euston Square, in the New Road. This grand but simple structure, which at the time of the publication was in course of erection. The work was designed by Philip Hardwick, architect of St. Katherine's Docks, Goldsmith's Hall, the City Club-house, and other building.[12]

The facade of the Euston Arch would occupy about 300 feet towards Drummond Street, opposite a wide opening into Euston Square. The principal elevation, as shown in the Engraving, consists of a Grecian Doric portico, with ante, and two lodges on each side, appropriated to the offices of the Company; the spaces between the columns and antse of the portico, and also of the lodges, being inclosed by very handsome, massive, iron gates.[12]

The whole of the works were proceeding very rapidly, and was expected that a portion of that magnificent Railway would be opened to the public after Midsummer. The Engraving has been reduced from a drawing by Thomas Allom, lithographed in very effective style by Mr. C. F. Cheffins, Southampton Buildings, Hulborn.[12]

Other lithographic work

In his studio at 9, Southampton Buildings, Holborn, Cheffins lithographed work for numerous other artists:

- 1837. In the month of August Cheffins published a lithographed plate, exhibiting a view of the apparatus used in the Francis B. Ogden, with a description of its construction and use.[13]

- 1837. Illustrations for Scenery in the north of Devon. George Rowe; Charles F. Cheffins; Paul Gauci; George Hawkins; Henry Strong; G. Wilkins. Published by J. Banfield, Ilfracombe.

- 1844. Illustrations for Quarterly papers on architecture. : Forty-one engravings, many of which are coloured. by Richard Hamilton Essex; John Richard Jobbins; John Henry Le Keux; Charles F. Cheffins; R Gould; Published by London : Iohan Weale.

- 1848. Illustration "Perspective view of machinery in Fulton's Clermont" for Henry Bernoulli Barlow[14]

- 1848. Illustrations for A sketch of the origin and progress of steam navigation from authentic documents by Bennet Woodcroft.[15]

- 1852. Lithographed illustrations of The Garden Companion and Florists' Guide by Thomas Moore.

- 1852. Lithographed London map designed by Benjamin Rees Davies.

- 1854. Drawing and publication of the famous map by John Snow showing the clusters of cholera cases in the London epidemic of 1854.[16]

Railroad surveys

On the completion of the parliamentary deposits for the Grand Junction Railway, Cheffins terminated his engagement with Stephenson, and, foreseeing that railway schemes were only then in their infancy, and that much work might be anticipated, by devoting himself exclusively to the surveying department of the profession, he established himself in London, and commenced business on his own account. He had the good fortune to retain the support and patronage of all those with whom he had been previously associated, besides adding many other names to his list of friends. Robert Stephenson, was among the latter, and under his direction and superintendence, he prepared many of the designs for the construction of the bridges on the London and Birmingham Railway, and was also engaged by him on various other matters. This kind friendship and support only ceased with Robert Stephenson's death, and Cheffins ever entertained a most lively regard for the man to whom his success in life might be fairly attributed.[2]

In his further professional career Cheffins complete numerous projects for the London and Blackwall Railway, the Great Eastern Railway (then the Eastern Counties Railway), the Trent Valley Line, and the North Staffordshire Railway, are a few of those which he lived to see brought to a successful completion, though in their course through both Houses of Parliament they had to sustain the heavy and determined opposition of other powerful companies and of large landed proprietors.

As a testimony of the esteem in which his services were held, during the many years he was engaged in these and other matters, a valuable service of plate was presented to him in the year 1846, the subscription being headed by the leading Engineers of the day. This token of regard has been handed down to his family to be kept by them as an heir-loom.

The last great scheme in which he was employed was the projected Great Eastern Northern Junction Railway Bill of 1860, (known familiarly as the ‘Coal line,’) which his good friend George Parker Bidder had placed in his hands, and in which he took a deep interest; but death cut him short whilst in the active discharge of his duties.[2]

Selected publications

Cheffins published dozens of maps, most of railways.[17] A selection:

- Charles F. Cheffins. London & Birmingham railway : plan of the line and adjacent country. London : C. F. Cheffins, 1835.

- Charles F. Cheffins. London and Birmingham railway : Map of the Railway from London to Box-Moor, and the adjacent Country. London : Charles F. Cheffins, 1 August 1837; 1838 edition with Thomas W. Streeter.

- Charles F. Cheffins; Thomas W. Streeter. Map of the Grand Junction Railway and adjacent country. 1838

- Charles Frederick Cheffins. Cheffins's Official Map of the Railway from London to Birmingham, Manchester and Liverpool. Wrightson & Webb. 1839

- Charles F. Cheffins; North Woolwich Railway. Plan and section of the North Woolwich Railway, in the counties of Essex and Kent. 1844

- Charles Frederick Cheffins. Cheffins's map of the railways in Great Britain : from the ordnance surveys. 1845

- Charles F. Cheffins. Map of the North Staffordshire lines : deposited with the Clerks of the Peace, Novr. 1845

- Charles F. Cheffins. Plans and Sections of the Norwich and Dereham Railway 1845

- Charles F. Cheffins. Furness Railway. London : C.F. Cheffins, lithographer, 1846.

- Charles Frederick Cheffins. Cheffins's Map of English & Scotch Railways: accurately delineating all the lines at present opened ; and those which are in progress. Corrected to the present time, the map also shows the main roads throughout the kingdom, with the distances between the towns, forming a complete guide for the traveller and tourist. 1847, 1850

- Charles F. Cheffins. Proposed railway from Cairo to the Sea of Suez. London : C.F. Cheffins, 184-

- Charles F. Cheffins. Cheffins's station map of the railways in Great Britain, from authentic sources. London : Charles F. Cheffins and Sons, 1859

Other maps, a selection:

- Charles Frederick Cheffins. Chart of the Gulf of Mexico, off St. Joseph's Island. R. Hastings, 1841

- Charles Frederick Cheffins. A map of the Republic of Texas and the adjacent territories, indicating the grants of land conceded under the Empresario System of Mexico. London : R. Hastings, 1841.

- Charles Frederick Cheffins; Monroe. Aranzas Bay, as surveyed by Captn. Monroe of the "Amos Wright". London : R. Hastings, 1841

- Benjamin Rees Davies; Charles F. Cheffins; Orr & Compy.; Letts, Son & Co.,; J. Cross & Son. London and its environs. London : Charles F. Cheffins. 1854[18]

- Charles Frederick Cheffins. Plan of the Manor of Newington Barrow, Otherwise Highbury, in Islington. C.F. Cheffins, Lithr. 1856

References

- ↑ The Solicitors' Journal and Reporter, Volume 5. 2 Nov. 1861.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Memories of Charles Frederick Cheffins" in: Proc. ICE. Institution of Civil Engineers (Great Britain). Vol XXI. (1861/2). pp. 578-80

- ↑ Chrimes, Michael M. "Robert Stephenson and planning the construction of the London and Birmingham Railway." Proceedings of the First International Congress on Construction History. Vol. 20. 2003.

- ↑ Michael Reeves Bailey. Robert Stephenson-the Eminent Engineer. Ashgate. 2003. p. 81

- ↑ Herapath's Railway Journal. Vol. 5. 1839. p. 389

- ↑ Benezit Dictionary of British Graphic Artists and Illustrators. Oxford University Press (2012) p. 154

- ↑ The London Gazette, 21 August 1860.

- ↑ The 1862 ICE Memories lists 22 October 1860 as date of death, yet describes that Cheffins died at the age of 54. With 10 September 1807 as date of birth, his date of death should have been after 10 September 1861.

- ↑ "Alleged infringement of patent-right: Court of Chancery, 30th June and 6th July, 1830." in: The Mechanics' Magazine Museum, Register, Journal And Gazette . Volume Thirteenth. (1830) p. 308-388.

- 1 2 Sholto Percy. "Alleged infringement of patent-right." in: Iron: An Illustrated Weekly Journal for Iron and Steel. Vol. 13 (1830). p. 381

- ↑ The Railway Record. Vol. 4 (1847). p. 670

- 1 2 3 "The London and Birmingham Railroad" in The Mirror, 8 April 1837.

- ↑ Bennet Woodcroft (1848) A Sketch of the Origin and Progress of Steam Navigation. p. 98

- ↑ Perspective view of machinery in Fulton's Clermont, 1848 at digitalgallery.nypl.org.

- ↑ Bennet Woodcroft. A sketch of the origin and progress of steam navigation from authentic documents (1848)

- ↑ K. Lee Lerner, Brenda Wilmoth Lerner (2006) Medicine, health, and bioethics: essential primary sources. p. xx.

- ↑ For a more complete listing, see worldcat.org

- ↑ Map online at vc.lib.harvard.edu

- Attribution

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from "Memories of Charles Frederick Cheffins" in: Proc. ICE. Institution of Civil Engineers (Great Britain). Vol XXI. (1861/2). pp. 578–80; and other public domain material from books and/or websites.

This article incorporates public domain material from "Memories of Charles Frederick Cheffins" in: Proc. ICE. Institution of Civil Engineers (Great Britain). Vol XXI. (1861/2). pp. 578–80; and other public domain material from books and/or websites.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Frederick Cheffins. |

- Charles Frederick Cheffins on gracesguide.co.uk

- Charles Frederick Cheffins on National Railway Museum; Data of 115 works by C.F. Cheffins