Greek scholars in the Renaissance

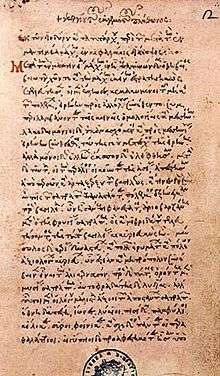

The migration waves of Byzantine scholars and émigrés in the period following the Crusader sacking of Constantinople and the end of the Byzantine Empire in 1453, is considered by many scholars key to the revival of Greek and Roman studies that led to the development of the Renaissance humanism[4] and science. These emigres were grammarians, humanists, poets, writers, printers, lecturers, musicians, astronomers, architects, academics, artists, scribes, philosophers, scientists, politicians and theologians.[5] They brought to Western Europe the relatively well-preserved remnants and accumulated knowledge of their own (Greek) civilization, which had mostly not survived the Dark Ages in the West.

Their main role within the Renaissance humanism was the teaching of the Greek language to their western counterparts in universities or privately together with the spread of ancient texts. Their forerunners were Barlaam of Calabria (Bernardo Massari) and Leonzio Pilato, both drawn from culturally Byzantine Calabria in southern Italy. The impact of these two scholars on the very first Renaissance humanists was indisputable.[6]

Collegio Pontifico Greco was a foundation of Gregory XIII, who established a college in Rome to receive young Greeks belonging to any nation in which the Greek Rite was used, and consequently for Greek refugees in Italy as well as the Ruthenians and Malchites of Egypt and Syria. These young men had to study the sacred sciences, in order to spread later sacred and profane learning among their fellow-countrymen and facilitate the reunion of the schismatical churches. The construction of the College and Church of S. Atanasio, joined by a bridge over the Via dei Greci, was begun at once. The same year (1577) the first students arrived, and until the completion of the college were housed elsewhere.[7]

Besides the southern Italians who inhabited ex-Byzantine territories of the peninsula and Sicily which were still closely connected with the Byzantine culture (and still Greek speaking in many areas), by 1500 there was a Greek speaking community of about 5,000 in Venice. The Venetians also ruled Crete, Dalmatia, and scattered islands and port cities of the former empire the populations of which were augmented by refugees from other Byzantine provinces who preferred Venetian to Ottoman governance. Crete was especially notable for the Cretan School of icon-painting, which after 1453 became the most important in the Greek world.[8]

Contribution of Greek scholars to the Italian Renaissance

Although ideas from ancient Rome already enjoyed popularity with the scholars of the 14th century and their importance to the Renaissance was undeniable, the lessons of Greek learning brought by Byzantine intellectuals changed the course of humanism and the Renaissance itself. While Greek learning affected all the subjects of the studia humanitatis, history and philosophy in particular were profoundly affected by the texts and ideas brought from Byzantium. History was changed by the re-discovery and spread of Greek historians’ writings, and this knowledge of Greek historical treatises helped the subject of history become a guide to virtuous living based on the study of past events and people. The effects of this renewed knowledge of Greek history can be seen in the writings of humanists on virtue, which was a popular topic. Specifically, these effects are shown in the examples provided from Greek antiquity that displayed virtue as well as vice. The philosophy of not only Aristotle but also Plato affected the Renaissance by causing debates over man’s place in the universe, the immortality of the soul, and the ability of man to improve himself through virtue. The flourishing of philosophical writings in the 15th century revealed the impact of Greek philosophy and science on the Renaissance. The resonance of these changes lasted through the centuries following the Renaissance not only in the writing of humanists, but also in the education and values of Europe and western society even to the present day.[10][11][12]

Deno Geanakopoulos in his work on the contribution of Byzantine scholars to Renaissance has summarised their input into three major shifts to Renaissance thought: 1) In early 14th century Florence from the early, central emphasis on rhetoric to one on metaphysical philosophy by means of introducing and reinterpretation of the Platonic texts, 2) In Venice-Padua by reducing the dominance of Averroist Aristotle in science and philosophy by supplementing but not completely replacing it with Byzantine traditions which utilised ancient and Byzantine commentators on Aristotle, 3) and earlier in the mid 15th century in Rome, through emphasis not on any philosophical school but through the production of more authentic and reliable versions of Greek texts relevant to all fields of humanism and science and with respect to the Greek fathers of the church. Hardly less important was their direct or indirect influence on exegesis of the New Testament itself through Bessarion's inspiration of Lorenzo Valla's biblical emendations of the Latin vulgate in the light of the Greek text.[13]

Scholars

- Leo Allatius, Rome, librarian of the library of Vatican

- George Amiroutzes, Florence, Aristotelian

- Henry Aristippus

- Michael Apostolius, Rome

- Aristobulus Apostolius

- Arsenius Apostolius

- John Argyropoulos, Universities of Florence, Rome

- Simon Atumano, Bishop of Gerace in Calabria

- Basilios Bessarion

- Barlaam of Seminara, he taught Petrarch some rudiments of Greek language

- Zacharias Calliergi, Rome

- Laonicus Chalcocondyles

- Demetrius Chalcondyles, Milan

- Theofilos Chalcocondylis, Florence

- Manuel Chrysoloras, Florence, Pavia, Rome, Venice, Milan

- John Chrysoloras, scholar and diplomat: relative of Manuel Chrysoloras, patron of Francesco Filelfo

- Andronicus Contoblacas, Basel, teacher of Johann Reuchlin

- Johannes Crastonis, Modena, Greek-Latin dictionary

- Andronicus Callistus, Rome

- Demetrius Cydones

- Mathew Devaris, Rome

- Demetrios Ducas

- Elia del Medigo, Venice

- Antonios Eparchos, Venice, scholar and poet

- Antonio de Ferraris, academic, doctor and humanist

- Theodorus Gaza, first dean of the University of Ferrara, Naples and Rome

- George Gemistos Plethon, teacher of Bessarion

- George of Trebizond, Venice, Florence, Rome

- George Hermonymus, University of Paris, teacher of Erasmus, Reuchlin, Budaeus and Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples

- Georgios Kalafatis (ca. 1652 – ca. 1720), Greek professor of theoretical and practical medicine[14]

- Andreas Musalus (ca. 1665/6 – ca. 1721), Greek professor of mathematics, philosopher and architectural theorist[15]

- Nicholas Kalliakis (Nicolai Calliachius) (1645–1707)-was a Greek scholar and philosopher who flourished in Italy.[16]

- Mathaeos Kamariotis

- Isidore of Kiev

- Ioannis Kigalas (ca. 1622 – 1687), Greek scholar and professor of Philosophy and Logic[17]

- Ioannis Kottounios, Padua

- Konstantinos Kallokratos

- Constantine Lascaris, University of Messina

- Janus Lascaris or Rhyndacenus, Rome

- Leonard of Chios, Greek-born Roman Catholic prelate

- Nikolaos Loukanis, Venice

- Maximus the Greek studied in Italy before moving to Russia

- Maximos Margunios, Venice

- Marcus Musurus, University of Padua

- Michael Tarchaniota Marullus, Ancona and Florence, friend and pupil of Jovianus Pontanus

- Leonardos Philaras (1595–1673), an early advocate for Greek independence[18]

- Leozio Pilatus, he taught Boccacio some rudiments of Greek language

- Maximus Planudes, Rome, Venice

- Franciscus Portus, Venice, Ferrara, Geneva

- John Servopoulos, scholar, professor, Oxford

- Nikolaos Sophianos, Rome, Venice: scholar and geographer, creator of the Totius Graeciae Descriptio

- Nicholas Leonicus Thomaeus, Venice, Padua

- Iakovos Trivolis, Venice

- Gregory Tifernas, Paris, teacher of Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples and Robert Gaguin

- Gerasimos Vlachos, Venice

- Francesco Maurolico, mathematician and astronomer from Sicily

Painting and music

- Marco Basaiti, painter

- Belisario Corenzio, painter, Napoli

- Michael Damaskenos, Venice, Cretan painter

- Thomas Flanginis, Venice, funded the establishment of the Flanginian Greek school for teachers

- El Greco, the nickname for the Cretan painter Dominikos Theotokopoulos, Italy, Spain

- Francisco Leontaritis, Italy, Bavaria: singer and composer

- Anna Notaras, Venice, first Greek printing press

- Angelos Pitzamanos (1467–1535), Cretan painter, Otranto, Southern Italy[19]

- Janus Plousiadenos, Venice, hymnographer and composer

- Theodore Poulakis, Venice, painter

- Emmanuel Tzanes, Venice, Cretan painter

- John Rhosos, Rome, Venice well-known scribe

- Antonio Vassilacchi, painter from Milos worked in Venice with Paolo Veronese

See also

- Byzantine art

- Cretan School

- Byzantine science

- Greek College

- List of Byzantine scholars

- Renaissance humanism

References

- ↑ Beckett, William à (1834). A universal biography: including scriptual, classical and mythological memoirs, together with accounts of many eminent living characters, Volume 1. Mayhew, Isaac and Co. p. 730. OCLC 15617538.

CHALCONDYLES (DEMETRIUS), a learned modern Greek, and a native of Athens, came over into Italy about 1447, and after a short abode at Rome

- ↑ Bèze, Théodore de; Summers, Kirk M. (2001). A view from the Palatine: the Iuvenilia of Théodore de Bèze. Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. p. 442. ISBN 9780866982795.

Demetrius Chalcondyles (1423-1511), a Greek refugee who taught Greek at Perugia, Padua, Florence, and Milan. Around 1493 he produced a Greek textbook for beginners.

- ↑ Rabil, Albert (1991). Knowledge, goodness, and power: the debate over nobility among quattrocento Italian humanists. Medieval & Renaissance Texts & Studies. p. 197. ISBN 0-86698-100-4.

John Argyropoulos (ca. 1415-87) played a prominent role in the revival of Greek philosophy in Italy. He came to Italy permanently in 1457 and held

- ↑ Byzantines in Renaissance Italy

- ↑ Greeks in Italy

- ↑ The Italian renaissance in its historical background, Denis Hay Cambridge University Press 1976

- ↑ De Meester, "Le Collège Pontifical Grec de Rome", Rome, 1910

- ↑ Maria Constantoudaki-Kitromilides in From Byzantium to El Greco,p.51-2, Athens 1987, Byzantine Museum of Arts

- ↑ Bunson, Matthew (2004). OSV's encyclopedia of Catholic history. Our Sunday Visitor Publishing. p. 141. ISBN 1-59276-026-0.

BESSARION, JOHN (c. 1395-1472) + Greek scholar, cardinal, and statesman. One of the foremost figures in the rise of the intellectual Renaissance in the

- ↑ Constantinople and the West by Deno John Geanakopulos- Italian Renaissance and thought and the role of Byzantine emigres scholars in Florence, Rome and Venice: A reassessment University of Wiskonshin Press, 1989

- ↑ From Byzantium to Italy: Greek Studies in the Italian Renaissance. by N. G. Wilson The Sixteenth Century Journal, Vol. 25, No. 3 (Autumn, 1994), pp. 743-744

- ↑ Eight philosophers of the Italian Renaissance, Paul Oskar Kristeller, Stanford University Press,1964

- ↑ Constantinople and the West by Deno John Geanakopulos- Italian Renaissance and thought and the role of Byzantine emigres scholars in Florence, Rome and Venice: A reassessment University of Wiskonshin Press, 1989

- ↑ Boehm, Eric H. (1995). Historical abstracts: Modern history abstracts, 1450-1914, Volume 46, Issues 3-4. American Bibliographical Center of ABC-Clio. p. 755. OCLC 701679973.

Between the 15th and 19th centuries the University of Padua attracted a great number of Greek students who wanted to study medicine. They came not only from Venetian dominions (where the percentage reaches 97% of the students of Italian universities) but also from Turkish-occupied territories of Greece. Several professors of the School of Medicine and Philosophy were Greeks, including Giovanni Cottunio, Niccolo Calliachi, Giorgio Calafatti...

- ↑ Convegno internazionale nuove idee e nuova arte nell '700 italiano, Roma, 19-23 maggio 1975. Accademia nazionale dei Lincei. 1977. p. 429. OCLC 4666566.

Nicolò Duodo riuniva alcuni pensatori ai quali Andrea Musalo, oriundo greco, professore di matematica e dilettante di architettura chiariva le nuove idée nella storia dell’arte.

- ↑ Feller, François-Xavier de (1782). Dictionnaire historique, Volume 2. Mathieu Rieger fils. p. 18. OCLC 310948713.

CALLIACHI, ( Nicolas ) grec de Candie, y naquit en 1645. Il profefla les belles

- ↑ Deutsche Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin. Institut für Griechisch-Römische Altertumskunde, Deutsche Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin. Zentralinstitut für Alte Geschichte und Archäologie (1956). Berliner byzantinistische Arbeiten, Volume 40. Akademie-Verlag. pp. 209–210.

John Cigala (born at Nicosia 1622). He studied at the College of Saint Athanasios, Rome (1635-1642), which he graduated as Doctor of Philosophy and Theology and at which he taught Greek successfully for eight years (1642-1650). From Rome he moved to Venice, where he practised law for a short time, therefore he may have also studied law. - In 1666 he was appointed Professor of Philosophy and Logic at the University of Padova. In 1678 he was appointed Professor to the second chair of Philosophy of the same University and in 1687 (214) to the first. From some time before 1678 he had also been censor of the books published by the S. Ufficio, Venice, which presupposed his Catholic loyalty, actually praised by D’ Alviani. His Greek and theological wisdom, his modesty, piety and other humane virtues are praised by Petin, Nicholas Bouboulios and D’ Alviani. In 1685 he appears as bestman at the marriage of Antonia daughter of Const. Tzane the Cretan painter to Mario Botza. Some of his epigrams have survived published in books of other scholars. Because of his duties as censor he seems to have lived in Venice from time to time. He died on the 5/11/1687.

- ↑ Merry, Bruce (2004). Encyclopedia of modern Greek literature. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 442. ISBN 0-313-30813-6.

Leonardos Filaras (1595-1673) devoted much of his career to coaxing Western European intellectuals to support Greek liberation. Two letters from Milton (1608-1674) attest Filaras’s ptriiotic crusade.

- ↑ Nano Chatzidakis: The character of the Velimezis Collection

Sources

- Deno J. Geanakoplos, Byzantine East and Latin West: Two worlds of Christendom in Middle Ages and renaissance. The Academy Library Harper & Row Publishers, New York, 1966.

- Deno J. Geanakoplos, (1958) A Byzantine looks at the renaissance, Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 1 (2);pp:157-62.

- Jonathan Harris, Greek Émigrés in the West, 1400-1520, Camberley: Porphyrogenitus, 1995.

- Louise Ropes Loomis (1908) The Greek Renaissance in Italy The American Historical Review, 13(2);pp:246-258.

- John Monfasani Byzantine Scholars in Renaissance Italy: Cardinal Bessarion and Other Émigrés: Selected Essays, Aldershot, Hampshire: Variorum, 1995.

- Steven Runciman, The fall of Constantinople, 1453. Cambridge University press, Cambridge 1965.

- Fotis Vassileiou & Barbara Saribalidou, Short Biographical Lexicon of Byzantine Academics Immigrants to Western Europe, 2007.

- Dimitri Tselos (1956) A Greco-Italian School of Illuminators and Fresco Painters: Its Relation to the Principal Reims

- Nigel G. Wilson. From Byzantium to Italy: Greek Studies in the Italian Renaissance. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.

External links

- Greece: Books and Writers.

- Michael D. Reeve, "On the role of Greek in Renaissance scholarship.'

- Jonathan Harris, 'Byzantines in Renaissance Italy'.

- Bilingual (Greek original / English) excerpts from Gennadios Scholarios' Epistle to Orators.

- Paul Botley, Renaissance Scholarship and the Athenian Calendar.

- Richard C. Jebb 'Christian Renaissance'.

- Karl Krumbacher: 'The History of Byzantine Literature: from Justinian to the end of the Eastern Roman Empire (527-1453)'.

- San Giorgio dei Greci and the Greek community of Venice

- Istituto Ellenico di Studi Byzantini and Postbyzantini di Venezia