Byzantine–Norman wars

| Byzantine–Norman Wars | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Byzantine Empire, |

Apulia and Calabria: Normans and Lombards Serbs (Duklja and Raška) | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Alexios I Comnenus, John II Comnenus Manuel I Comnenus Andronicus Comnenus Isaac II Angelus |

Robert Guiscard, Bohemond, George of Antioch, William II Constantine Bodin, Margaritus of Brindisi | ||||||

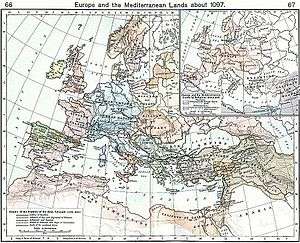

A number of wars between the Normans and the Eastern Roman Empire were fought from c. 1040 until 1185 when the last Norman invasion of East Roman territory was defeated. At the end of the conflict, neither the Normans nor the Byzantines could boast much power; by the mid-13th century exhaustive fighting with other powers had undermined the rule of both, leading to the Byzantines losing Asia Minor to the Turks in the 14th century, and the Normans losing Sicily to the Hohenstaufen, who in turn were succeeded by the Angevins and finally the Aragonese.

Norman conquest of southern Italy

The Normans had come from the Duchy of Normandy in West Francia, which in 911 had been granted to the Viking Rollo in the Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte by the French king Charles the Simple. The Normans and their new land took the name of these "Northmen". During the time that the Normans had conquered southern Italy, the Byzantine Empire was in a state of internal decay; the administration of the Empire had been wrecked, the efficient government institutions that provided Basil II with a quarter of a million troops and adequate resources by taxation had collapsed within a period of three decades. Attempts by Isaac I Komnenos and Romanos IV Diogenes to reverse the situation proved unfruitful. The premature death of the former and the overthrow of the latter led to further collapse as the Normans consolidated their conquest of Sicily and Italy.

Reggio Calabria, the capital of the tagma of Calabria, was captured by Robert Guiscard in 1060. At the time, the Byzantines held a few coastal towns in Apulia, including the capital of the catepanate of Italy, Bari. Otranto was besieged and fell in the October 1068; in the same year, the Normans besieged Bari itself and, after defeating the Byzantines in a series of battles in Apulia, and after any attempt of relief had failed, the city surrendered in April 1071, ending the Byzantine presence in southern Italy.

First Norman invasion of the Balkans (1081–1085)

Following their successful conquest of southern Italy, the Normans saw no reason to stop; Byzantium was decaying further still and looked ripe for conquest. When Alexios I Comnenus ascended to the throne of Byzantium, his early emergency reforms, such as requisitioning Church money - a previously unthinkable move - proved too little to stop the Normans.

Led by the formidable Robert Guiscard and his son Bohemund, they took Dyrrhachium and Corfu, and laid siege to Larissa in Thessaly (see Battle of Dyrrhachium). Alexios suffered several defeats before being able to strike back with success. He enhanced this by bribing the German king Henry IV with 360,000 gold pieces to attack the Normans in Italy, which forced the Normans to concentrate on their defenses at home in 1083–1084. He also secured the alliance of Henry, Count of Monte Sant'Angelo, who controlled the Gargano Peninsula and dated his charters by Alexios' reign. Henry's allegiance was to be the last example of Byzantine political control on peninsular Italy. The Norman danger ended for the time being with the death of Robert Guiscard in 1085 combined with a Byzantine victory and crucial Venetian aid allowed the Byzantines to retake the Balkans.

Rebellion of Antioch (1104–1140)

Following the First Crusade, a large number of Normans naturally joined in what appeared to be a great expedition into the unknown where land and loot was plentiful. During this time, the Byzantines were able to utilize, to some extent, the aggressive Normans to defeat the Seljuk Turks in numerous battles and many cities fell. However, when Antioch fell the Normans refused to hand it over although in time Byzantine domination was established. With the death of John Comnenus the Norman Principality of Antioch rebelled once again, attacking Cyprus and invading Cilicia, which also rebelled. The quick and energetic response of Manuel Comnenus allowed the Byzantines to extract an even more favorable modus vivendi with Antioch (in 1145 being forced to provide Byzantium with a contingent of troops and allow a Byzantine garrison in the city). However, the city was given guarantees of protection against Turkic attack and Nur ad-Din Zangi abstained from attacking the northern parts of the Crusader states as a result.

Second Norman invasion of the Balkans (1147–1149)

In 1147 the Byzantine empire under Manuel I Comnenus was faced with war by Roger II of Sicily, whose fleet had captured the Byzantine island of Corfu and plundered Thebes and Corinth. However, despite being distracted by a Cuman attack in the Balkans, in 1148 Manuel enlisted the alliance of Conrad III of Germany, and the help of the Venetians, who quickly defeated Roger with their powerful fleet. In ca. 1148, the political situation in the Balkans was divided by two sides, one being the alliance of the Byzantines and Venice, the other the Normans and Hungarians. The Normans were sure of the danger that the battlefield would move from the Balkans to their area in Italy.[1] The Serbs, Hungarians and Normans exchanged envoys, being in the interest of the Normans to stop Manuel's plans to recover Italy.[2] In 1149, Manuel recovered Corfu and prepared to take the offensive against the Normans, while Roger II sent George of Antioch with a fleet of 40 ships to pillage Constantinople's suburbs.[3] Manuel had already agreed with Conrad on a joint invasion and partition of southern Italy and Sicily. The renewal of the German alliance remained the principal orientation of Manuel's foreign policy for the rest of his reign, despite the gradual divergence of interests between the two empires after Conrad's death.[4] However, while Manuel was in Avlona planning the offensive across the Adriatic, the Serbs revolted, posing a danger to the Byzantine Adriatic bases.[2]

The death of Roger in February 1154, who was succeeded by William I, combined with the widespread rebellions against the rule of the new King in Sicily and Apulia, the presence of Apulian refugees at the Byzantian court, and Frederick Barbarossa's (Conrad's successor) failure to deal with the Normans encouraged Manuel to take advantage of the multiple instabilities that existed in the Italian peninsula.[5] He sent Michael Palaiologos and John Doukas, both of whom held the high imperial rank of sebastos, with Byzantine troops, 10 Byzantine ships, and large quantities of gold to invade Apulia (1155).[6][7] The two generals were instructed to enlist the support of Frederick Barbarossa, since he was hostile to the Normans of Sicily and was south of the Alps at the time, but he declined because his demoralised army longed to get back north of the Alps as soon as possible.b[›] Nevertheless, with the help of disaffected local barons including Count Robert of Loritello, Manuel's expedition achieved astonishingly rapid progress as the whole of southern Italy rose up in rebellion against the Sicilian Crown, and the untried William I.[4] There followed a string of spectacular successes as numerous strongholds yielded either to force or the lure of gold.[8][9]

Third Norman invasion of the Balkans (1185–1186)

Although the last invasions and last large scale conflict between the two powers lasted less than two years, the third Norman invasions came closer still to taking Constantinople. The incompetent rule of Andronicus Comnenus allowed the Normans to go unchecked towards the Byzantine capital giving Thessalonica a savage sack (a grim portent of what Constantinople would face in 20 years time). The resulting panic, however, allowed Isaac Angelus to take the throne and, after defeating the confident opponent, push the invaders back to Sicily, with the exception of the County palatine of Cephalonia and Zakynthos, the latter remaining in the hands of Norman admiral Margaritus of Brindisi and his successors until 1479.

Aftermath

With the Normans unable to take the Balkans, they turned their attention to European affairs. The Byzantines meanwhile had not possessed the will or the resources for any Italian invasion since the days of Manuel Comnenus. After the third invasion, the survival of the Empire became more important to the Byzantines than a mere province on the other side of the Adriatic Sea. The Norman dynasty was succeeded 1194 by the Hohenstaufen, themselves being replaced in 1266 by the Angevins. The successive Sicilian rulers would eventually continue the Norman policy of domination over post-Byzantine states in the Ionian Sea and Greece, attempting to assert suzerainty over Corfu, finally conquered in 1260, the County palatine of Cephalonia and Zakynthos, the Despotate of Epirus and other territories.

References

- ↑ Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti (1940). Društveni i istoriski spisi.

Око 1148. год. ситуација на Балкану била је овака. На једној страни беху у савезу Византија и Млеци, а на другој Нормани и Мађари. Нормани су били побеђени и у опасности да се ратиште пренесе с Балкана на њихово подручје у Италију. Да омету Манојла у том плану они настоје свима средствима, да му направе што више неприлика код куће. Доиста, 1149. год. јавља се нови устанак Срба против Ви- зантије, који отворено помажу Мађари. Цар ...

- 1 2 Fine 1991, p. 237.

- ↑ Norwich 1995, pp. 98, 103.

- 1 2 Magdalino 2005, p. 621.

- ↑ Duggan 2003, p. 122.

- ↑ Birkenmeier 2002, p. 114.

- ↑ Norwich 1995, p. 112.

- ↑ Brooke 2004, p. 482.

- ↑ Magdalino 2002, p. 67.

Sources

- Primary

- Anna Comnena, translated by E.R.A Sewter (1969). The Alexiad. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-044215-4.

- Secondary

- Birkenmeier, John W. (2002). "The Campaigns of Manuel I Komnenos". The Development of the Komnenian Army: 1081–1180. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-11710-5.

- Brooke, Zachary Nugent (2004). "East and West:1155–1198". A History of Europe, from 911 to 1198. Routledge (UK). ISBN 0-415-22126-9.

- Duggan, Anne J. (2003). "The Pope and the Princes". Adrian IV, the English Pope, 1154–1159: Studies and Texts edited by Brenda Bolton and Anne J. Duggan. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 0-7546-0708-9.

- Fine, Jr. John Van Antwerp (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

- Christopher Gravett and David Nicolle, (2006). The Normans: Warrior Knights and their Castles. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 1-84603-088-9.

- John Haldon, (2000). The Byzantine Wars. The Mill: Tempest. ISBN 0-7524-1795-9.

- Richard Holmes, (1988). The World Atlas of Warfare: Military Innovations That Changed the Course of History. Middlesex: Penguin. ISBN 0-670-81967-0.

- Magdalino, Paul (2005). "The Byzantine Empire (1118–1204)". The New Cambridge Medieval History edited by Rosamond McKitterick, Timothy Reuter, Michael K. Jones, Christopher Allmand, David Abulafia, Jonathan Riley-Smith, Paul Fouracre, David Luscombe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-41411-3.

- Magdalino, Paul (2002). The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 1143–1180. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52653-1.

- Norwich, John Julius (1998). A Short History of Byzantium. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-025960-0.

- Norwich, John Julius (1995). Byzantium: The Decline and Fall. London: Viking. ISBN 0-670-82377-5.