Whirligig

A whirligig is an object that spins or whirls, or has at least one part that spins or whirls. Whirligigs are also known as pinwheels, buzzers, comic weathervanes, gee-haws, spinners, whirlygigs, whirlijig, whirlyjig, whirlybird, or plain whirly. Whirligigs are most commonly powered by the wind but can be hand, friction, or motor powered. They can be used as a kinetic garden ornament. They can be designed to transmit sound and vibration into the ground to repel burrowing rodents in yards, gardens, and backyards.

Types of whirligigs

Whirligigs can be divided into four categories: Button, Friction, String and Wind Driven.

Button whirligigs

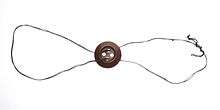

Button whirligigs, also known as button spinners and buzzers, are the oldest known whirligigs. They require only a piece of clay or bone and a strip of hide. Native American cultures had their own version of this toy in 500 BC. Many a child of the Great Depression from the southern Appalachians and Ozarks remembers a button or token, or coin and a string as the primary spinning toy of their youth.

Button whirligigs are simple spinning toys whereby two looped ends of twisting thread are pulled with both arms, causing the button to spin. Button whirligigs are often seen today in craft shops and souvenir stores in the southern Appalachian Mountains.

Buzzers

Buzzers are button whirligigs that make a sound which can be modulated by how quickly the button is spinning and by the tightness of the string. A buzzer is often constructed by running string through two of the holes on a large button and is a common and easily made toy.

A buzzer (buzz, bullroarer, button-on-a-string), is an ancient mechanical device used for ceremonial purposes and as a toy. It is constructed by centering an object at the midpoint of a cord or thong and winding the cord while holding the ends stationary. The object is whirled by alternately pulling and releasing the tension on the cord. The whirling object makes a buzzing or humming sound, giving the device its common name.

American Indians used the buzzer as a toy and, also ceremonially, as to call up the wind. Early Indian buzzers were constructed of wood, bone, or stone, and date from at least the Fourche Maline Culture, c. 500 B.C.[2][3]

| North American Buzzers, Buzzes, etc. | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

1912 "A Buzzer of Bone"[4] |

1892 "Buzz Toy"[5] |

1916 "Whirligig Made from a Large Button"[6] |

Friction and string whirligigs

String powered whirligigs require the operator to wrap the string around a shaft and then pull the string to cause the whirligig’s motion. String Whirligigs have ancient origins. The bamboo-copter or bamboo butterfly, was invented in China in 400 BC. While the initial invention did not use string to launch a propeller, later Chinese versions did.[7] The first known depictions of whirligigs are string powered versions in tapestries from medieval times.

Friction whirligigs, also called Gee-Haws, depend on the holder rubbing a stick against a notched shaft resulting in a propeller at the end of the shaft turning, largely as the result of the vibration carried along the shaft. The motion needed to power a friction whirligig is very similar to rubbing sticks together to create fire. Friction whirligigs are another staple of craft shops and souvenir stores in the Appalachian Mountains.

Wind-driven whirligigs

A wind-driven whirligig transfers the energy of the wind into either a simple release of kinetic energy through rotation or a more complicated transfer of rotational energy to power a simple or complicated mechanism that produces repetitive motions and/or creates sounds. The wind simply pushes on the whirligig turning one part of it and it then uses inertia.

The simplest and most common example of a wind-driven whirligig is the pinwheel. The pinwheel demonstrates the most important aspect of a whirligig, blade surface. Pinwheels have a large cupped surface area which allows the pinwheel to reach its terminal speed fairly quickly at low wind speed.

Increasing the blade area of the whirligig increases the surface area so more air particles collide with the whirligig. This causes the drag force to reach its maximum value and the whirligig to reach its terminal speed in less time. Conversely the terminal speed is smaller when thin or short blades with a smaller surface area are utilized, resulting in the need for a higher wind speed to start and operate the whirligig.[8] Whirligigs come in a range of sizes and configurations, bounded only by human ingenuity. The two blade non-mechanical model is the most prevalent; exemplified by the classic Cardinal with Wings illustrated at right.

History

Etymology of the word

The word whirligig derives from two middle English words: "whirlen" (to whirl) and "gigg" (top),[9] or literally "to whirl a top". The Oxford English Dictionary cites the Promptorium parvulorum (ca. 1440), the first English-Latin dictionary, which contains the definition "Whyrlegyge, chyldys game, Latin: giracu-lum[10] It is therefore likely the 1440 version of whirligig referred to a spinning toy or toys.

Origins and evolution

The actual origin of whirligigs is unknown. Both farmers and sailors use weathervanes on an ongoing basis and the assumption is one or both groups are likely the originators. By 400 BC the bamboo-copter or dragon butterfly, a helicopter-like rotor launched by rolling a stick had been invented in China.[7] Wind driven whirligigs were technically possible by 700 AD when the Sasanian Empire began using windmills to lift water for irrigation. The weathervane which dates to the Sumerians in 1600-1800 BC, is the second component of wind driven whirligigs.[11]

In early Chinese, Egyptian, Persian, Greek and Roman civilizations there are ample examples of weathervanes but as yet, no examples of a propeller driven whirligig. A grinding corn doll of ancient Egyptian origin demonstrates that string operated whirligigs were already in use by 100 BC.[12]

The first known visual representation of a European whirligig is contained in a medieval tapestry that depicts children playing with a whirligig consisting of a hobbyhorse on one end of a stick and a four blade propeller at the other end.[13]

For reasons that are not clear, whirligigs in the shape of the cross became a fashionable allegory in paintings of the fifteenth and sixteenth century. An oil by Hieronymus Bosch probably completed between 1480 and 1500 and known as the Christ Child with a Walking Frame, contains a clear illustration of a string powered whirligig.[14]

A book published in Stuttgart in 1500 shows the Christ child in the margin with a string powered whirligig.[15]

The Jan Provost attributed late sixteenth-century painting ‘’Virgin and Child in a Landscape’’ clearly shows the Christ child holding a whirligig as well.[16]

The American version of the wind driven whirligig probably originated with the immigrant population of the United Kingdom as whirligigs are mentioned in early American colonial times. How the wind driven whirligig evolved in America is not fully known, though there are some markers.

George Washington brought ‘’whilagigs’’ home from the Revolutionary War.[17] What type is unknown.

By the mid 18th century weathervanes had evolved to include free moving "wings".[18] These "wings" could be human arms; pitchforks; spoons, or virtually any type of implement. The 1819 publication by Washington Irving of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow contains the following description: ’’a little wooden warrior who, armed with a sword in each hand, was most valiantly fighting the wind on the pinnacle of the barn’’.[19]

By the latter half of the 19th century constructing wind driven whirligigs had become a pastime and art form. What began as a simple turning of artificial feathers in the wind advanced into full blown mechanisms producing both motion and sound. Unfortunately both the exposure to the weather and the fragile nature of whirligigs means very few wind driven whirligigs from this era survive. The period between 1880 and 1900 brought rapid geographic expansion of whirligigs across the US. After 1900, production seemed for the most part to center on the southern Appalachians. Craftsman from the southern Appalachians continued to produce whirligigs into the 20th century. During the Great Depression a resurgence in production by craftsman and amateurs was attributed to the need for ready cash.

Today Whirligigs are used as toys for children, as garden structures designed to keep birds or other garden pests away, as decorative yard art and as art.

Whirligigs as art

Whirligigs have become art. A number of museums now have collections, or examples in their collections.[20]

Whirligigs in literature

William Shakespeare, in Twelfth Night, uses the whirligig as a metaphor for "what goes around, comes around."[21]

In his play Cupid's Whirligig, Edward Sharpham has the deity of love cast a spell over a group of Londoners so that one falls for another, who falls for another, and so on until the final person falls for the first: a cupid's whirligig.

O. Henry wrote a short story called "The Whirligig of Life", about a mountain couple who decide to divorce and the events that lead to their remarriage told from the perspective of the judge.[22]

Lloyd Biggle, Jr. wrote a novel titled The Whirligig of Time as part of his science fiction series featuring Jan Darzek, a former private detective.[23]

In Whirligig, a novel by Paul Fleischman, a boy makes a mistake that takes the life of a young girl and is sent on a cross country journey building whirligigs.

In the Newbery Award-Winning young adult novel Missing May by Cynthia Rylant, Ob, the main character's uncle, makes whirligigs as a hobby. After his wife who loved the whirligigs dies, the whirligigs continue to move and symbolize the fact that life must go on for Ob.

Whirligigs in the movies

In the movie Twister, Helen Hunt's aunt Meg (played by Lois Smith) has a large collection of metal kinetic art whirligigs in her front yard to warn her of approaching tornadoes.[24]

Whirligigs in science

Manu Prakash, an assistant professor of bioengineering, and Saad Bhamla, a postdoctoral student at Stanford University built in 2016 an inexpensive, hand-powered centrifuge that's based on this ancient toy and could help doctors working in developing countries.[25]

Whirligigs as folk art

When whirligigs became recognized as American folk art isn’t clear, but today they are a well established sub-category. With recognition folk art whirligigs have increased in value.

The photo on the right is of a traditional whirligig commonly found in Bali, Indonesia. They are still available, and are often used in the rice paddies as the sound they make when the wind blows scares the birds away. This example was found near Clarkrange, Tennessee on the Highway 127 Corridor Sale. It represents an interesting example of a combination mechanical and sound producing whirligig.

The propeller, the Balinese farmer and the bull are of tin. The farmer and bull are painted but the propeller blades are not. The body is of hand whittled bamboo, fastened with rusty nails and wire and a single piece of string. There are still pencil marks where various pieces were centered and/or aligned.

The farmer is connected to the shaft of the whirligig by a bamboo stick with an offset where the stick connects to the shaft. The result is: as the shaft turns the farmer’s arm lifts from the offset shaft which makes the farmer pull the string which lifts the bull’s head. The shaft contains a second feature, a set of knockers that create a bit of music on raised pieces of bamboo. There are a total of six knockers which strike six bamboo plates. The bamboo plates are raised by placing a circular piece of bamboo or something similar between the knockers and the bamboo base. Each rotation causes three knockers to hit plates so the sound is actually different at each rotation. The knockers are nailed in pattern to the shaft.

Whirligigs from folk artist Reuben Aaron Miller and others are considered highly collectable. However, whirligigs' value as folk art has been uneven. At a 1998 auction at Skinner Galleries, a 19th-century Uncle Sam with saw and flag in excellent condition sold for $12,650.[26] At a 2000 auction at Skinner Galleries a 19th-century polychrome carved pine and copper band figure whirligig in excellent condition sold for $10,925 and an early 20th-century bike rider of painted wood and sheet metal sold for $3,450.[27] In 2005, a 20th-century folk art whirligig in good condition brought $2,900 at an auction at Horst Auction Center in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.[28]

The modern craftsman

There is still a role for the solitary craftsman, whittler or inventor as evidenced by the following cast of modern whirligig builders.

Lester Gay of Fountain, North Carolina made whirligigs from his retirement until his death in 1998. Mr. Gay’s wind driven whirligigs were made of bicycle rims placed at nearly uniform height to create a "garden of whirligigs". He never sold one personally. At the end of his life there were said to be over 250 whirligigs in his yard. The whole collection was donated to the Fountain, North Carolina Volunteer Fire Department, which sold them off at $75 each.[29]

Near Plantersville, Alabama between 2001 and 2008 Edith Lawrence made whirligigs that her husband Gene sold from their front yard. Gene became known locally as Whirligig Man. Edith's whirligigs were of the wind driven type, typically of cast off plastic. All of the proceeds they earned went to their local church. Edith died in December 2008 and Gene abandoned the business soon after.[30]

Mr. Elmer Preston (b.3/17/1874-d.10/1/1974)lived in South Hadley, Massachusetts worked in a traditional folk manner, with the classic themes of Farmer Cutting Wood, etc.

Ander Lunde of Chapel Hill, North Carolina is credited with reviving the whirligig during the 1980s. A well-known painter and wood sculptor, Lunde won First Prize for a whirligig sculpture in the 1981 Durham (North Carolina) Art Guild Juried Exhibition. Lunde received two honorable mentions for his whirligigs at the first statewide Juried Exhibition of North Carolina Crafts in 1983.[31] Lunde's contribution to the literature on whirligigs is substantial, with a total of eight how-to build whirligig books to his credit. (See bibliography.)

Vollis Simpson has constructed a "whirligig farm" on his land in Lucama, North Carolina, which has been profiled by PBS,[32] the subject of an online photographic essay at the Minnesota Museum of Science,[33] and an article in American Profile. One of Simpson's creations stands in front of the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland. Simpson was named the 2012 Arts and Culture winner of Southern Living's Heroes of the New South Awards.[34] Simpson's farm contains some thirty to forty whirligigs at any given time, some of which reach fifty feet in height. The whirligigs are made from castoff metal machine parts and an assortment of odd and colorful pieces of various origins.,[35] He sells smaller versions to the public, but only from his farm.

Wilson, North Carolina holds an annual Whirligig Festival in November of each year which includes a whirligig building contest complete with nominal cash prizes. The contest was judged in part by Vollis Simpson.[36]

Bibliography

- Beard, D.C. The American Boys Handy Book: What to Do and How to Do It. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. (1907).

- Bishop, Robert and Coblentz, Patricia; A Gallery of American Weathervanes and Whirligigs (ISBN 0525476520 / 0-525-47652-0); E.P. Dutton, NY, 1981.

- Bridgewater, Alan; and Bridgewater, Gill; The Wonderful World of Whirligigs and Wind Machines (ISBN 0830683496 / 0-8306-8349-6); Tab Books, 1990

- Burda, Cindy; Wind Toys That Spin, Sing, Twirl & Whirl; (ISBN 0806939346 / 0-8069-3934-6); Sterling, New York, 1999

- Fitzgerald, Ken; Weathervanes and Whirligigs; Bramhall House, 1967

- Hall, A. Neely; Perkins, Dorothy. Handicraft for Handy Girls: Practical Plans for Work and Play. Boston: Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Co. (1916).

- Kroeber, Alfred L. "The Arapaho," Part IV "Religion, Bulletin American Museum of Natural History Vol. XVIII. New York: Published by Order of the Trustees (1907)

- Lunde, Anders S.; Whirligigs: Design and Construction; Mother Earth News, 1983

- Lunde, Anders S.; Whirligigs In Silhouette: 25 New Patterns (ISBN 0866750142 / 0-86675-014-2); Modern Handicraft Inc., Kansas City, MO; 1989

- Lunde, Anders S.; Whirligigs for Children Young and Old; (ISBN 9780801982347); Chilton Book Co., Radnor, PA; 1992

- Lunde, Anders S.; Easy to Make Whirligigs; Dover Publications, 1996

- Lunde, Anders S.; Making Animated Whirligigs; Dover Publications, 1998

- Lunde, Anders S.; Whimisical Whirligigs; (ISBN 0486412334); Dover Publications, 2000

- Lunde, Anders S.; Action Whirligigs: 25 Easy to Do Projects; Dover Publications, 2003

- Marling, Karal Ann; Wind & Whimsy: Weathervanes and Whirligigs from Twin Cities Collections; Minneapolis Institute of Arts,2007

- Pettit, Florence Harvey; How to Make Whirligigs and Whimmy Diddles and Other American Folkcraft Objects (ISBN 0690413890 / 0-690-41389-0); Thomas Y. Crowell, New York, New York, U.S.A., 1972

- Pierce, Sharon; Making Whirligigs and Other Wind Toys; (ISBN 0806979801 / 0-8069-7980-1); Sterling Pub Co Inc; New York, New York; 1985

- Powell, J.W. (Director). Ninth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution 1887-'88. Washington, D.C.: Government printing Office (1892).

- Schoonmaker, David & Woods, Bruce; Whirligigs & Weathervanes: A Celebration of Wind Gadgets With Dozens of Creative Projects to Make; Sterling/Lark, New York, 1991

- Schwartz, Renee, Wind Chimes & Whirligigs, Kids Can Press, 2007

- Skinner, Alanson. "Notes on the Eastern Cree and Northern Saulteaux", Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History, pp. 1–178. New York: Published by Order of the Trustees (1912).

- Wells, J.B. Toy Buzz. US Patent #193201. US Patent Office (May 21, 1877).

- Wiley, Jack; How to Make Propeller-Animated Whirligigs: Penguin, Folk Rooster, Dove, Pink Flamingo, Flying Unicorn & Roadrunner, Solipaz Publishing Co., 1993

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Whirligig. |

- ↑ Beard, The American Boys Handy Book, p. 360: "A Saw-Mill; it was generally made out of the top of a tin blacking-box, with the rim knocked off and the edge cut into notches like a saw. Two strings passing through two holes near the centre gave a revolving motion to the 'buzzer'."

- ↑ Kroeber, "The Arapaho: Religion", p 396: "A bone buzzer made of the foot-bone of a cow, and called, like a bull-roarer, 'hateikuuca,' is sometimes used in the ghost-dance to start the singing."

- ↑ Skinner, "'Notes on the Eastern Cree and Northern Saulteaux", p. 141: "Bull roarers of several kinds not only serve as amusements but are carried by hunters, who use them to bring the wind. The outfit consists of a central wooden disc or cylinder or of a scaphoid bone of a deer or moose. A string is attached to each side and a grip or handle place transversely at right angles to the end of the string. The whole is held loosely and the central disc revolved until the string is very much twisted. Then, by tightening and loosening the string, the cord unwinds and rewinds itself with great rapidity causing the middle piece to revolve and make a loud, buzzing noise."

- ↑ Skinner, "'Notes on the Eastern Cree and Northern Saulteaux", p. 140: "Fig. 50 (50-8052). A Buzzer of Bone."

- ↑ Powell, Ninth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology, p. 378: "Fig. 376.—Buzz Toy."

- ↑ Hall, Handicraft for Handy Girls, p. 190: "Fig. 347.—Whirligig Made from a Large Button."

- 1 2 Leishman, J. Gordon (2006). Principles of Helicopter Aerodynamics. Cambridge University Press. p. 7. ISBN 0-521-85860-7, ISBN 978-0-521-85860-1

- ↑ "It’s About Time".

- ↑ Merriam-Webster Dictionary

- ↑ The Promptorium Parvulorum by Galfridus (Anglicus), Anthony Lawson Mayhew, Winchester Cathedral. Chapter Library.

- ↑ "Timeline of Inventions and Patents".

- ↑ Whirligigs & Weathervanes; Schoonmaker, David and Woods, Bruce; Sterling; 1992; pg 12.

- ↑ Williams, Lindsay; Whirligig Pleasure Charlotte Sun Herald; August 17, 2000.

- ↑

- ↑ Paris, Lateinisches Stundenbuch (Livre d'heures), um 1500, Handschrift, Stuttgart, Württembergische Landesbibliothek, Cod. brev. 5. Buchausstattung. Christusknabe mit dem Windrad, Miniatur (in der Bordüre)

- ↑ National Gallery Picture Library, London UK.

- ↑ The woodworker's guide to pricing your work; Dan Ramsey; Popular Woodworking Books, 2005; pg 46.

- ↑

- ↑ The Legend of Sleepy Hollow; Irving; Washington; pg 48.

- ↑ American Visionary Art Museum.

- ↑ "The whirligig of time". eNotes.

- ↑ "The Whirligig of Life by O. Henry". literaturecollection.com.

- ↑ The Whirligig of Time

- ↑ Warner Brothers, Director Jan de Bont, 1996

- ↑ http://www.nature.com/articles/s41551-016-0009 Hand-powered ultra low-cost paper centrifuge

- ↑ New York Times.

- ↑ Gilbert, Anne. "Whimsical whirligigs caught in the winds of folk art collectors". WP. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ↑ Sunday News Lancaster, PA ‘’Whirligig spins way to $2,900’’ February 27, 2005

- ↑ Alex Albright, 15 March 1998 Roadside America

- ↑ Kathleen McQueen Wright. "Southern Artistic Touch". southernartistictouch.blogspot.com.

- ↑ Making Animated Whirligigs; Lunde, Ander; Dover Publications; Unabridged edition (January 23, 1998); pg 125

- ↑ "OFF THE MAP . Travelogue . Vollis Simpson - PBS". pbs.org.

- ↑ "From Windmills to Whirligigs". smm.org.

- ↑ "2012 Heroes of the New South Awards". Southern Living.

- ↑ Andrea. Wizard of Whirligigs, American Profile; 16 June 2003.

- ↑ "ナイル熱". wilsonwhirligigfestival.com.

External links

- Whirligig Carver Inspired By Slovenian Childhood Memories Video produced by Wisconsin Public Television

- Whirligig physics analysed and used to design a cheap centrifuge (paperfuge)