Burney Relief

|

A likely representation of either Ereshkigal or Ishtar | |

| Material | Clay |

|---|---|

| Size |

Height: 49.5 cm (19.5 in) Width: 37 cm (15 in) Thickness: 4.8 cm (1.9 in) |

| Created | 19th-18th century BCE |

| Period/culture | Old Babylonian |

| Place | Made in Babylonia |

| Present location | Room 56, British Museum, London |

| Identification | Loan 1238 |

| Registration | 2003,0718.1 |

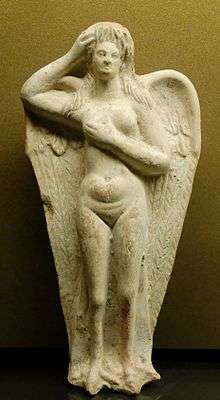

The Burney Relief (also known as the Queen of the Night relief) is a Mesopotamian terracotta plaque in high relief of the Isin-Larsa- or Old-Babylonian period, depicting a winged, nude, goddess-like figure with bird's talons, flanked by owls, and perched upon two lions.

The relief is displayed in the British Museum in London, which has dated it between 1800 and 1750 BCE. It originates from southern Mesopotamia, but the exact find-site is unknown. Apart from its distinctive iconography, the piece is noted for its high relief and relatively large size, which suggest that it was used as a cult relief, making it a very rare survival from the period. However, whether it represents Lilitu, Inanna/Ishtar, or Ereshkigal is under debate. The authenticity of the object has been questioned from its first appearance in the 1930s, but opinion has generally moved in its favour over the subsequent decades.

Provenance

Initially in the possession of a Syrian dealer, who may have acquired the plaque in southern Iraq in 1924, the relief was deposited at the British Museum in London and analysed by Dr. H.J. Plenderleith in 1933. However, the Museum declined to purchase it in 1935, whereupon the plaque passed to the London antique dealer Sidney Burney; it subsequently became known as the "Burney Relief".[1] The relief was first brought to public attention with a full-page reproduction in The Illustrated London News, in 1936.[2] From Burney, it passed to the collection of Norman Colville, after whose death it was acquired at auction by the Japanese collector Goro Sakamoto. British authorities, however, denied him an export licence. The piece was loaned to the British Museum for display between 1980 and 1991, and in 2003 the relief was purchased by the Museum for the sum of £1,500,000 as part of its 250th anniversary celebrations. The Museum also renamed the plaque the "Queen of the Night Relief".[3] Since then, the object has toured museums around Britain.

Unfortunately, its original provenance remains unknown. The relief was not archaeologically excavated, and thus we have no further information where it came from, or in which context it was discovered. An interpretation of the relief thus relies on stylistic comparisons with other objects for which the date and place of origin have been established, on an analysis of the iconography, and on the interpretation of textual sources from Mesopotamian mythology and religion.[4]

Description

Detailed descriptions were published by Henri Frankfort (1936),[1] by Pauline Albenda (2005),[5] and in a monograph by Dominique Collon, curator at the British Museum, where the plaque is now housed.[3] The composition as a whole is unique among works of art from Mesopotamia, even though many elements have interesting counterparts in other images from that time.[6]

Physical aspect

The relief is a terracotta (fired clay) plaque, 50 by 37 centimetres (20 in × 15 in) large, 2 to 3 centimetres (0.79 to 1.18 in) thick, with the head of the figure projecting 4.5 centimetres (1.8 in) from the surface. To manufacture the relief, clay with small calcareous inclusions was mixed with chaff; visible folds and fissures suggest the material was quite stiff when being worked.[7] The British Museum's Department of Scientific Research reports, "it would seem likely that the whole plaque was moulded" with subsequent modelling of some details and addition of others, such as the rod-and-ring symbols, the tresses of hair and the eyes of the owls.[8] The relief was then burnished and polished, and further details were incised with a pointed tool. Firing burned out the chaff, leaving characteristic voids and the pitted surface we see now; Curtis and Collon believe the surface would have appeared smoothed by ochre paint in antiquity.[9]

In its dimensions, the unique plaque is larger than the mass-produced terracotta plaques – popular art or devotional items – of which many were excavated in house ruins of the Isin-Larsa and Old Babylonian periods.[nb 1]

Overall, the relief is in excellent condition. It was originally received in three pieces and some fragments by the British Museum; after repair, some cracks are still apparent, in particular a triangular piece missing on the right edge, but the main features of the deity and the animals are intact. The figure's face has damage to its left side, the left side of the nose and the neck region. The headdress has some damage to its front and right hand side, but the overall shape can be inferred from symmetry. Half of the necklace is missing and the symbol of the figure held in her right hand; the owls' beaks are lost and a piece of a lion's tail. A comparison of images from 1936 and 2005 shows that some modern damage has been sustained as well: the right hand side of the crown has now lost its top tier, and at the lower left corner a piece of the mountain patterning has chipped off and the owl has lost its right-side toes.[10] However, in all major aspects, the relief has survived intact for more than 3,500 years.

Traces of red pigment still remain on the figure's body that was originally painted red overall. The feathers of her wings and the owls' feathers were also colored red, alternating with black and white. By Raman spectroscopy the red pigment is identified as red ochre, the black pigment, amorphous carbon ("lamp black") and the white pigment gypsum.[11] Black pigment is also found on the background of the plaque, the hair and eyebrows, and on the lions' manes.[nb 2] The pubic triangle and the areola appear accentuated with red pigment but were not separately painted black.[11] The lions' bodies were painted white. The British Museum curators assume that the horns of the headdress and part of the necklace were originally colored yellow, just as they are on a very similar clay figure from Ur.[nb 3] They surmise that the bracelets and rod-and-ring symbols might also have been painted yellow. However, no traces of yellow pigment now remain on the relief.

The female figure

The nude female figure is realistically sculpted in high-relief. Her eyes, beneath distinct, joined eyebrows, are hollow, presumably to accept some inlaying material – a feature common in stone, alabaster, and bronze sculptures of the time,[nb 4] but not seen in other Mesopotamian clay sculptures. Her full lips are slightly upturned at the corners. She is adorned with a four-tiered headdress of horns, topped by a disk. Her head is framed by two braids of hair, with the bulk of her hair in a bun in the back and two wedge-shaped braids extending onto her breasts.

The stylized treatment of her hair could represent a ceremonial wig. She wears a single broad necklace, composed of squares that are structured with horizontal and vertical lines, possibly depicting beads, four to each square. This necklace is virtually identical to the necklace of the god found at Ur, except that the latter's necklace has three lines to a square. Around both wrists she wears bracelets which appear composed of three rings. Both hands are symmetrically lifted up, palms turned towards the viewer and detailed with visible life-, head- and heart lines, holding two rod-and-ring symbols of which only the one in the left hand is well preserved. Two wings with clearly defined, stylized feathers in three registers extend down from above her shoulders. The feathers in the top register are shown as overlapping scales (coverts), the lower two registers have long, staggered flight feathers that appear drawn with a ruler and end in a convex trailing edge. The feathers have smooth surfaces; no barbs were drawn. The wings are similar but not entirely symmetrical, differing both in the number of the flight feathers[nb 5] and in the details of the coloring scheme.[nb 6]

Her wings are spread to a triangular shape but not fully extended. The breasts are full and high, but without separately modelled nipples. Her body has been sculpted with attention to naturalistic detail: the deep navel, structured abdomen, "softly modeled pubic area"[nb 7] the recurve of the outline of the hips beneath the iliac crest, and the bony structure of the legs with distinct knee caps all suggest "an artistic skill that is almost certainly derived from observed study".[5] A spur-like protrusion, fold, or tuft extends from her calves just below the knee, which Collon interprets as dewclaws. Below the shin, the figure's legs change into those of a bird. The bird-feet are detailed,[nb 8] with three long, well-separated toes of approximately equal length. Lines have been scratched into the surface of the ankle and toes to depict the scutes, and all visible toes have prominent talons. Her toes are extended down, without perspective foreshortening; they do not appear to rest upon a ground line and thus give the figure an impression of being dissociated from the background, as if hovering.[5]

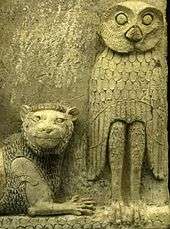

The animals and background

The two lions have a male mane, patterned with dense, short lines; the manes continue beneath the body.[nb 9] Distinctly patterned tufts of hair grow from the lion's ears and on their shoulders, emanating from a central disk-shaped whorl. They lie prone, their heads are sculpted with attention to detail, but with a degree of artistic liberty in their form, e.g., regarding their rounded shapes. Both lions look towards the viewer, and both have their mouths closed.

The owls shown are recognizable, but not sculpted naturalistically: the shape of the beak, the length of the legs, and details of plumage deviate from those of the owls that are indigenous to the region.[nb 10] Their plumage is colored like the deity's wings in red, black and white; it is bilaterally similar but not perfectly symmetrical. Both owls have one more feather on the right-hand side of their plumage than on the left-hand side. The legs, feet and talons are red.

The group is placed on a pattern of scales, painted black. This is the way mountain ranges were commonly symbolized in Mesopotamian art.

Context

Date and place of origin

Stylistic comparisons place the relief at the earliest into the Isin–Larsa period,[12] or slightly later, to the beginning of the Old Babylonian period.[nb 11] Frankfort especially notes the stylistic similarity with the sculpted head of a male deity found at Ur,[1][nb 3] which Collon finds to be "so close to the Queen of the Night in quality, workmanship and iconographical details, that it could well have come from the same workshop."[13] Therefore, Ur is one possible city of origin for the relief, but not the only one: Edith Porada points out the virtual identity in style that the lion's tufts of hair have with the same detail seen on two fragments of clay plaques excavated at Nippur.[14][nb 12] And Agnès Spycket reported on a similar necklace on a fragment found in Isin.[15]

Geopolitical context

A creation date at the beginning of the second millennium BCE places the relief into a region and time in which the political situation was unsteady, marked by the waxing and waning influence of the city states of Isin and Larsa, an invasion by the Elamites, and finally the conquest by Hammurabi in the unification in the Babylonian empire in 1762 BCE.

300 to 500 years earlier, the population for the whole of Mesopotamia was at its all-time high of about 300,000. Elamite invaders then toppled the third Dynasty of Ur and the population declined to about 200,000; it had stabilized at that number at the time the relief was made.[16] Cities like Nippur and Isin would have had on the order of 20,000 inhabitants and Larsa maybe 40,000; Hammurabi's Babylon grew to 60,000 by 1700 BCE.[17] A well-developed infrastructure and complex division of labour is required to sustain cities of that size. The fabrication of religious imagery might have been done by specialized artisans: large numbers of smaller, devotional plaques have been excavated that were fabricated in molds.

Even though the fertile crescent civilizations are considered the oldest in history, at the time the Burney Relief was made other late bronze age civilizations were equally in full bloom. Travel and cultural exchange were not commonplace, but nevertheless possible.[nb 13] To the east, Elam with its capital Susa was in frequent military conflict with Isin, Larsa and later Babylon. Even further, the Indus Valley Civilization was already past its peak, and in China, the Erlitou culture blossomed. To the southwest, Egypt was ruled by the 12th dynasty, further to the west the Minoan civilization, centred on Crete with the Old Palace in Knossos, dominated the Mediterranean. To the north of Mesopotamia, the Anatolian Hittites were establishing their Old Kingdom over the Hattians; they brought an end to Babylon's empire with the sack of the city in 1531 BCE. Indeed, Collon mentions this raid as possibly being the reason for the damage to the right-hand side of the relief.[18]

Religion

The size of the plaque suggests it would have belonged in a shrine, possibly as an object of worship; it was probably set into a mud-brick wall.[19] Such a shrine might have been a dedicated space in a large private home or other house, but not the main focus of worship in one of the cities' temples, which would have contained representations of gods sculpted in the round. Mesopotamian temples at the time had a rectangular cella often with niches to both sides. According to Thorkild Jacobsen, that shrine could have been located inside a brothel (see below).[20]

Art history

Compared with how important religious practice was in Mesopotamia, and compared to the number of temples that existed, very few cult figures at all have been preserved. This is certainly not due to a lack of artistic skill: the "Ram in a Thicket" (see image below) shows how elaborate such sculptures could have been, even 600 to 800 years earlier. It is also not due to a lack of interest in religious sculpture: deities and myths are ubiquitous on cylinder seals and the few steles, kudurrus, and reliefs that have been preserved. Rather, it seems plausible that the main figures of worship in temples and shrines were made of materials so valuable they could not escape looting during the many shifts of power that the region saw.[21] The Burney Relief is comparatively plain, and so survived. In fact, the relief is one of only two existing large, figurative representations from the Old Babylonian period. The other one is the top part of the Code of Hammurabi, which was actually discovered in Elamite Susa, where it had been brought as booty (see image).

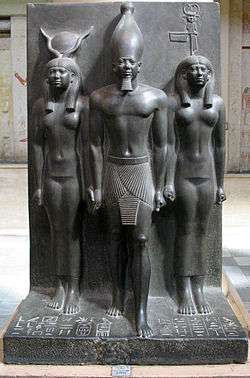

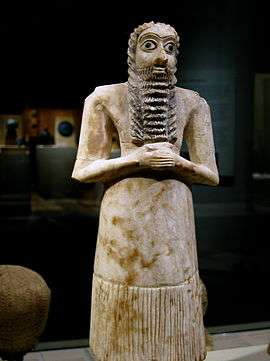

A static, frontal image is typical of religious images intended for worship. Symmetric compositions are common in Mesopotamian art when the context is not narrative.[nb 14] Many examples have been found on cylinder seals. Three-part arrangements of a god and two other figures are common, but five-part arrangements exist as well. In this respect, the relief follows established conventions. In terms of representation, the deity is sculpted with a naturalistic but "modest" nudity, reminiscent of Egyptian goddess sculptures, which are sculpted with a well-defined navel and pubic region but no details; there, the lower hemline of a dress indicates that some covering is intended, even if it does not conceal. In a typical statue of the genre, Pharao Menkaura and two goddesses, Hathor and Bat are shown in human form and sculpted naturalistically, just as in the Burney Relief; in fact, Hathor has been given the features of Queen Khamerernebty II (see image and article). Depicting an anthropomorphic god as a naturalistic human is an innovative artistic idea that may well have diffused from Egypt to Mesopotamia, just like a number of concepts of religious rites, architecture, the "banquet plaques", and other artistic innovations previously.[22] In this respect, the Burney Relief shows a clear departure from the schematic style of the worshiping men and women that were found in temples from periods about 500 years earlier (see image). It is also distinct from the next major style in the region: Assyrian art, with its rigid, detailed representations, mostly of scenes of war and hunting (see image).

The extraordinary survival of the figure type, though interpretations and cult context shifted over the intervening centuries, is expressed by the cast terracotta funerary figure of the 1st century BCE, from Myrina on the coast of Mysia in Asia Minor, where it was excavated by the French School at Athens, 1883; the terracotta is conserved in the Musée du Louvre (illustrated left).

- Comparisons

An example of elaborate Sumerian sculpture: the "Ram in a Thicket", excavated in the royal cemetery of Ur by Leonard Woolley and dated to about 2600–2400 BCE. Wood, gold leaf, lapis lazuli and shell. British Museum, ME 122200.

An example of elaborate Sumerian sculpture: the "Ram in a Thicket", excavated in the royal cemetery of Ur by Leonard Woolley and dated to about 2600–2400 BCE. Wood, gold leaf, lapis lazuli and shell. British Museum, ME 122200.- The only other surviving large image from the time: top part of the Code of Hammurabi, c. 1760 BCE. Hammurabi before the sun-god Shamash. Note the four-tiered, horned headdress, the rod-and-ring symbol and the mountain-range pattern beneath Shamash' feet. Black basalt. Louvre, Sb 8.

A typical representation of a 3rd millennium BCE Mesopotamian worshipper, Eshnunna, about 2700 BCE. Alabaster. Metropolitan Museum of Art 40.156.

A typical representation of a 3rd millennium BCE Mesopotamian worshipper, Eshnunna, about 2700 BCE. Alabaster. Metropolitan Museum of Art 40.156. Deity representation on Assyrian relief. Blessing genie, about 716 BCE. Relief from the palace of Sargon II. Louvre AO 19865

Deity representation on Assyrian relief. Blessing genie, about 716 BCE. Relief from the palace of Sargon II. Louvre AO 19865

Compared to visual artworks from the same time, the relief fits quite well with its style of representation and its rich iconography. The images below show earlier, contemporary, and somewhat later examples of woman and goddess depictions.

- Contemporaries

Ishtar. Moulded plaque, Eshnunna, early 2nd. millennium. Louvre, AO 12456

Ishtar. Moulded plaque, Eshnunna, early 2nd. millennium. Louvre, AO 12456 Woman, from a temple. Old Babylonian period. British Museum ME 135680

Woman, from a temple. Old Babylonian period. British Museum ME 135680

Iconography

Mesopotamian religion recognizes literally thousands of deities, and distinct iconographies have been identified for about a dozen. Less frequently, gods are identified by a written label or dedication; such labels would only have been intended for the literate elites. In creating a religious object, the sculptor was not free to create novel images: the representation of deities, their attributes and context were as much part of the religion as the rituals and the mythology. Indeed, innovation and deviation from an accepted canon could be considered a cultic offense.[23] The large degree of similarity that is found in plaques and seals suggests that detailed iconographies could have been based on famous cult statues; they established the visual tradition for such derivative works but have now been lost.[24] It appears, though, that the Burney Relief was the product of such a tradition, not its source, since its composition is unique.[6]

Frontal nudity

The frontal presentation of the deity is appropriate for a plaque of worship, since it is not just a "pictorial reference to a god" but "a symbol of his presence".[1] Since the relief is the only existing plaque intended for worship, we do not know whether this is generally true. But this particular depiction of a goddess represents a specific motif: a nude goddess with wings and bird's feet. Similar images have been found on a number of plaques, on a vase from Larsa, and on at least one cylinder seal; they are all from approximately the same time period.[25] In all instances but one, the frontal view, nudity, wings, and the horned crown are features that occur together; thus, these images are iconographically linked in their representation of a particular goddess. Moreover, examples of this motif are the only existing examples of a nude god or goddess; all other representations of gods are clothed.[26] The bird's feet have not always been well preserved, but there are no counter-examples of a nude, winged goddess with human feet.

Horned crown

The horned crown – usually four-tiered– is the most general symbol of a deity in Mesopotamian art. Male and female gods alike wear it. In some instances, "lesser" gods wear crowns with only one pair of horns, but the number of horns is not generally a symbol of "rank" or importance. The form we see here is a style popular in Neo-Sumerian times and later; earlier representations show horns projecting out from a conical headpiece.[27]

Wings

Winged gods, other mythological creatures, and birds are frequently depicted on cylinder seals and steles from the 3rd millennium all the way to the Assyrians. Both two-winged and four-winged figures are known and the wings are most often extended to the side. Spread wings are part of one type of representation for Ishtar.[28] However, the specific depiction of the hanging wings of the nude goddess may have evolved from what was originally a cape.[29]

Rod and ring symbol

This symbol may depict the measuring tools of a builder or architect or a token representation of these tools. It is frequently depicted on cylinder seals and steles, where it is always held by a god – usually either Shamash, Ishtar, and in later Babylonian images also Marduk– and often extended to a king.[27]

Lions

Lions are chiefly associated with Ishtar or with the male gods Shamash or Ningirsu.[20] In Mesopotamian art, lions are nearly always depicted with open jaws. H. Frankfort suggests that The Burney Relief shows a modification of the normal canon that is due to the fact that the lions are turned towards the worshipper: the lions might appear inappropriately threatening if their mouths were open.[1]

Owls

No other examples of owls in an iconographic context exist in Mesopotamian art, nor are there textual references that directly associate owls with a particular god or goddess.

Mountains

A god standing on or seated on a pattern of scales is a typical scenery for the depiction of a theophany. It is associated with gods who have some connection with mountains but not restricted to any one deity in particular.[20]

Identification

The figure has initially been identified as a depiction of Ishtar (Inanna)[nb 15][2] but almost immediately other arguments have been put forward:

Lilitu

The identification of the relief as depicting "Lilith" has become a staple of popular writing on that subject. Raphael Patai (1990)[30] believes the relief to be the only extant depiction of a Sumerian female demon called lilitu and thus to define lilitu's iconography. Citations regarding this assertion lead back to Henri Frankfort (1936). Frankfort himself based his interpretation of the deity as the demon Lilith on the presence of wings, the birds' feet and the representation of owls. He cites the Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh as a source that such "creatures are inhabitants of the land of the dead".[31] In that text Enkidu's appearance is partially changed to that of a feathered being, and he is led to the nether world where creatures dwell that are "birdlike, wearing a feather garment".[1] This passage reflects the Sumerians' belief in the nether world, and Frankfort cites evidence that Nergal, the ruler of the underworld, is depicted with bird's feet and wrapped in a feathered gown.

However Frankfort did not himself make the identification of the figure with Lilith; rather he cites Emil Kraeling (1937) instead. Kraeling believes that the figure "is a superhuman being of a lower order"; he does not explain exactly why. He then goes on to state "Wings [...] regularly suggest a demon associated with the wind" and "owls may well indicate the nocturnal habits of this female demon". He excludes Lamashtu and Pazuzu as candidate demons and states: "Perhaps we have here a third representation of a demon. If so, it must be Lilîtu [...] the demon of an evil wind", named ki-sikil-lil-la[nb 16] (literally "wind-maiden" or "phantom-maiden", not "beautiful maiden", as Kraeling asserts (see below)).[32] This ki-sikil-lil is an antagonist of Inanna (Ishtar) in a brief episode of the epic of Gilgamesh, which is cited by both Kraeling and Frankfort as further evidence for the identification as Lilith, though this appendix too is now disputed. In this episode, Inanna's holy Huluppu tree is invaded by malevolent spirits. Frankfort quotes a preliminary translation by Gadd (1933): "in the midst Lilith had built a house, the shrieking maid, the joyful, the bright queen of Heaven". However modern translations have instead: "In its trunk, the phantom maid built herself a dwelling, the maid who laughs with a joyful heart. But holy Inanna cried."[33] The earlier translation implies an association of the demon Lilith with a shrieking owl and at the same time asserts her god-like nature; the modern translation supports neither of these attributes. In fact, Cyril J. Gadd (1933), the first translator, writes: "ardat lili (kisikil-lil) is never associated with owls in Babylonian mythology" and "the Jewish traditions concerning Lilith in this form seem to be late and of no great authority".[34] This single line of evidence was taken as virtual proof of the identification of the Burney Relief with "Lilith" may have been motivated by later associations of "Lilith" in later Jewish sources.

The association of Lilith with owls in later Jewish literature such as the Songs of the Sage (1st century BCE) and Babylonian Talmud (5th century CE) is derived from a reference to a liliyth among a list of wilderness birds and animals in Isaiah (7th century BCE), though some scholars, such as Blair (2009)[35][36] consider the pre-Talmudic Isaiah reference to be non-supernatural, and this is reflected in some modern Bible translations:

- Isaiah 34:13 Thorns shall grow over its strongholds, nettles and thistles in its fortresses. It shall be the haunt of jackals, an abode for ostriches. 14 And wild animals shall meet with hyenas; the wild goat shall cry to his fellow; indeed, there the night bird (lilit or lilith) settles and finds for herself a resting place. 15 There the owl nests and lays and hatches and gathers her young in her shadow; indeed, there the hawks are gathered, each one with her mate. (ESV)

Today, the identification of the Burney Relief with Lilith is questioned,[37] and the figure is now generally identified as the goddess of love and war.[38]

Ishtar

50 years later, Thorkild Jacobsen substantially revised this interpretation and identified the figure as Inanna (Akkadian: Ishtar) in an analysis that is primarily based on textual evidence.[20] According to Jacobsen:

- The hypothesis that this tablet was created for worship makes it unlikely that a demon was depicted. Demons had no cult in Mesopotamian religious practice since demons "know no food, know no drink, eat no flour offering and drink no libation."[nb 17] Therefore, "no relationship of giving and taking could be established with them";

- The horned crown is a symbol of divinity, and the fact that it is four-tiered suggests one of the principal gods of the Mesopotamian pantheon;

- Inanna was the only goddess that was associated with lions, for example a hymn by En-hedu-ana specifically mentions "Inanna, seated on crossed (or harnessed) lions"[nb 18]

- The goddess is depicted standing on mountains. According to text sources, Inanna's home was on Kur-mùsh, the mountain crests. Iconographically, other gods were depicted on mountain scales as well, but there are examples in which Inanna is shown on a mountain pattern and another god is not, i.e. the pattern was indeed sometimes used to identify Inanna.;[39]

- The rod-and-ring symbol, her necklace and her wig are all attributes that are explicitly referred to in the myth of Inanna's descent into the nether world.[40]

- Jacobsen quotes textual evidence that the Akkadian word eššebu (owl) corresponds to the Sumerian word ninna, and that the Sumerian Dnin-ninna (Divine lady ninna) corresponds to the Akkadian Ishtar. The Sumerian ninna can also be translated as the Akkadian kilili, which is also a name or epithet for Ishtar. Inanna/Ishtar as harlot or goddess of harlots was a well known theme in Mesopotamian mythology and in one text, Inanna is called kar-kid (harlot) and ab-ba-[šú]-šú, which in Akkadian would be rendered kilili. Thus there appears to be a cluster of metaphors linking prostitute and owl and the goddess Inanna/Ishtar; this could match the most enigmatic component of the relief to a well known aspect of Ishtar. Jacobsen concludes that this link would be sufficient to explain talons and wings, and adds that nudity could indicate the relief was originally the house-altar of a bordello.[20]

Ereshkigal

In contrast, the British Museum does acknowledge the possibility that the relief depicts either Lilith or Ishtar, but prefers a third identification: Ishtar's antagonist and sister Ereshkigal, the goddess of the underworld.[41] This interpretation is based on the fact that the wings are not outspread and that the background of the relief was originally painted black. If this were the correct identification, it would make the relief (and by implication the smaller plaques of nude, winged goddesses) the only known figurative representations of Ereshkigal.[5] Edith Porada, the first to propose this identification, associates hanging wings with demons and then states: "If the suggested provenience of the Burney Relief at Nippur proves to be correct, the imposing demonic figure depicted on it may have to be identified with the female ruler of the dead or with some other major figure of the Old Babylonian pantheon which was occasionally associated with death."[42] No further supporting evidence was given by Porada, but another analysis published in 2002 comes to the same conclusion. E. von der Osten-Sacken describes evidence for a weakly developed but nevertheless existing cult for Ereshkigal; she cites aspects of similarity between the goddesses Ishtar and Ereshkigal from textual sources – for example they are called "sisters" in the myth of "Inanna's descent into the nether world" – and she finally explains the unique doubled rod-and-ring symbol in the following way: "Ereshkigal would be shown here at the peak of her power, when she had taken the divine symbols from her sister and perhaps also her identifying lions".[43]

Authenticity

The 1936 London Illustrated News feature had "no doubt of the authenticity" of the object which had "been subjected to exhaustive chemical examination" and showed traces of bitumen "dried out in a way which is only possible in the course of many centuries".[2] But stylistic doubts were published only a few months later by D. Opitz who noted the "absolutely unique" nature of the owls with no comparables in all of Babylonian figurative artefacts.[44] In a back-to-back article, E. Douglas Van Buren examined examples of Sumerian [sic] art, which had been excavated and provenanced and she presented examples: Ishtar with two lions, the Louvre plaque (AO 6501) of a nude, bird-footed goddess standing on two Ibexes[45] and similar plaques, and even a small haematite owl, although the owl is an isolated piece and not in an iconographical context.

A year later Frankfort (1937) acknowledged Van Buren's examples, added some of his own and concluded "that the relief is genuine". Opitz (1937) concurred with this opinion, but reasserted that the iconography is not consistent with other examples, especially regarding the rod-and-ring symbol. These symbols were the focus of a communication by Pauline Albenda (1970) who again questioned the relief's authenticity. Subsequently the British Museum performed thermoluminescence dating which was consistent with the relief being fired in antiquity; but the method is imprecise when samples of the surrounding soil are not available for estimation of background radiation levels. A rebuttal to Albenda by Curtis and Collon (1996) published the scientific analysis; the British Museum was sufficiently convinced of the relief to purchase it in 2003. The discourse continued however: in her extensive reanalysis of stylistic features, Albenda once again called the relief "a pastiche of artistic features" and "continue[d] to be unconvinced of its antiquity".[46]

Her arguments were rebutted in a rejoinder by Collon (2007), noting in particular that the whole relief was created in one unit, i.e. there is no possibility that a modern figure or parts of one might have been added to an antique background; she also reviewed the iconographic links to provenanced pieces. In concluding Collon states: "[Edith Porada] believed that, with time, a forgery would look worse and worse, whereas a genuine object would grow better and better. [...] Over the years [the Queen of the Night] has indeed grown better and better, and more and more interesting. For me she is a real work of art of the Old Babylonian period."

In 2008/9 the relief was included in exhibitions on Babylon at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, the Louvre in Paris, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.[47]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Such plaques are about 10 to 20 centimetres (3.9 to 7.9 in) in their longest dimension. Cf. the plaque AO 6501 at the Louvre, the plaque BM WA 1994-10-1, 1 at the British Museum, or an actual mould: BM WA 1910-11-12, 4, also at the British Museum (Curtis 1996)

- ↑ cf. the color-scheme reconstruction on the British Museum page

- 1 2 According to the British Museum, this figure – of which only the upper part is preserved – presumably represents the sun-god Shamash (cf. details of 1931,1010.2)

- ↑ cf. the Male Worshiper and Standing Female Figure in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ↑ The right wing has eight flight feathers, the left wing has seven.

- ↑ The lower register of the right wing breaks the white-red-black pattern of the other three registers with a white-black-red-black-white sequence.

- ↑ Albenda (2005) notes "a tiny vertical indentation" but Collon (2007b) clarifies that this is merely a missing flake over a repaired fracture.

- ↑ cf. image of the foot of an Indian falcon

- ↑ D. Opitz (1936) interprets this mane pattern as depicting the indigenous Barbary lion. D. Collon prefers an interpretation as the related Asiatic lion and notes that a skin in the Natural History Museum in London shows the distinctive whorl in the mane that is often represented in Mesopotamian art (Collon 2005, 34), but also in Egyptian art (cf. Tutanhkamun headrest).

- ↑ Iraq's indigenous owls without ear-tufts include the Barn Owl (Tyto alba) – this is the owl that D. Collon believes to be represented in the relief (Collon 2005, 36) – the Little Owl (Athene noctua lilith) and the Tawny Owl(Strix aluco).

- ↑ The relief is therefore neither Sumerian or Akkadian - that would have been even earlier - nor Assyrian - that would located it to northern Mesopotamia.

- ↑ cf. Plates 142:8 and 142:10 in McCown 1978. By stratification with dated clay-tablets, one of these similar fragments has been assigned to the Isin–Larsa period (dates between 2000 and 1800 BCE), the other to the adjacent Old Babylonian period (dates between 1800 and 1700 BCE) (short chronology).

- ↑ cf. the Egyptian 12th dynasty story of Sinuhe

- ↑ A narrative context depicts an event, such as the investment of a king. There, the king opposes a god, and both are shown in profile. Whenever a deity is depicted alone, a symmetrical composition is more common. However, the shallow relief of the cylinder seal entails that figures are shown in profile; therefore, the symmetry is usually not perfect.

- ↑ Inanna is the Sumerian name and Ishtar the Akkadian name for the same goddess. Sacral text was usually written in Sumerian at the time the relief was made, but Akkadian was the spoken language; this article therefore uses the Akkadian name Ishtar for consistency, except where "Inanna" has been used by the authors whose sources are quoted.

- ↑ ki-sikil-lil-la (Krealing) and ki-sikil-lil-la-ke (Albenda) appear to be mistaken readings of the original Sumerian passage from the Gilgamesh epos: ki-sikil lit. ki- earth-untouched/pure i.e. virgin or maiden, lil2 wind; breath; infection; phantom; -la- is gen. case marker and -ke4 erg. case marker, both are required by the grammatical context (in this passage: "kisikil built for herself") but the case markers are not part of the noun.

- ↑ cf. line 295 in "Inanna's descent into the nether world"

- ↑ Jacobsen quotes Inana C, line 23 and the motif of Inana standing on lions is well attested from seals and plaques (cf. the image of Ishtar, above);

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Frankfort 1937.

- 1 2 3 Davis 1936.

- 1 2 Collon 2003.

- ↑ Albenda, Pauline (April–June 2005). "The Queen of the Night Plaque A Revisit". Journal of the American Oriental Society. American Oriental Society. 125 (2): 171–190. JSTOR 20064325.

- 1 2 3 4 Albenda 2005.

- 1 2 Janson, Horst Woldemar; Janson, Anthony F. (1 July 2003). History of art: the Western tradition (6th Revised ed.). Prentice-Hall. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-13-182895-7.

- ↑ Collon 2003, 13.

- ↑ quoted in Collon 2007b

- ↑ Curtis 1996

- ↑ cf. Davis 1936; Collon 2005

- 1 2 Collon 2007b.

- ↑ Van Buren 1936.

- ↑ Collon 2005, 20.

- ↑ Porada 1980.

- ↑ quoted in Collon 2007b.

- ↑ Thompson 2004.

- ↑ George Modelski, quoted in Thompson 2004.

- ↑ Collon 2005, 22.

- ↑ Frankfort 1937; Jacobsen 1987.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jacobsen 1987.

- ↑ Spycket 1968, 11; Ornan 2005, 60 ff.

- ↑ Kaelin 2006.

- ↑ Ornan 2005, 8 ff.

- ↑ Collon 2007.

- ↑ Van Buren (1936) shows three such examples, Barrelet (1952) shows six more such representations and Collon (2005) adds yet another plaque to the canon.

- ↑ cf. Ornan 2005, Fig. 1–220.

- 1 2 Black 1992.

- ↑ Collon 2007, 80.

- ↑ Barrelet 1952.

- ↑ Patai 1990, 221.

- ↑ Gilgamesh, Plate VII, col. IV

- ↑ Kraeling 1937.

- ↑ Gilgameš, Enkidu and the nether world, lines 44-46

- ↑ Gadd 1933.

- ↑ Judit M. Blair De-demonising the Old Testament; an investigation of Azazel, Lilith, Deber, Qeteb and Reshef in the Hebrew Bible 2009

- ↑ Isaiah 34:14

- ↑ Lowell K. Handy article Lilith Anchor Bible Dictionary

- ↑ Bible Review Vol 17 Biblical Archaeology Society - 2001 "LILITH? In the 1930s, scholars identified the voluptuous woman on this terracotta plaque (called the Burney Relief) as the Babylonian demoness Lilith. Today, the figure is generally identified as the goddess of love and war "

- ↑ Ornan 2005, 61 f.

- ↑ Jacobsen 1987, (original at "Inana's descent to the nether world")

- ↑ "Queen of the night relief". The British Museum. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ Porada 1980, 260.

- ↑ Von der Osten-Sacken 2002.

- ↑ Opitz 1936.

- ↑ "(AO 6501) Déesse nue ailée figurant probablement la grande déesse Ishtar". Musée du Louvre (in French). Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ Albenda, Pauline (Apr–Jun 2005). "The "Queen of the Night" Plaque: A Revisit". Journal of the American Oriental Society. American Oriental Society. 125 (2): 171–190.

- ↑ "British Museum collection database"

Bibliography

- Albenda, Pauline (2005). "The "Queen of the Night" Plaque: A Revisit". Journal of the American Oriental Society. American Oriental Society. 125 (2): 171–190. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 20064325.

- Barrelet, Marie-Thérèse (1952). "A Propos d'une Plaquette Trouvée a Mari". Syria: Revue d'Art Oriental et d'Archéologie (in French). Paris: Librairie Orientaliste Paul Greuthner. XXIX: 285–293. doi:10.3406/syria.1952.4791.

- Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (1992). Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia, an Illustrated Dictionary. (illustrations by Tessa Rickards). Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-70794-0.

- "British Museum collection database" Queen of the Night/Burney Relief website page, accessed Feb 7, 2016

- Collon, Dominique (2005). The Queen of the Night. British Museum Objects in Focus. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-5043-7.

- Collon, Dominique (2007). "Iconographic Evidence for some Mesopotamian Cult Statues". In Groneberg, Brigitte; Spieckermann, Hermann. Die Welt der Götterbilder. Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft. 376. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 57–84. ISBN 978-3-11-019463-0.

- Collon, Dominique (2007b). "The Queen Under Attack – A rejoinder" (PDF). Iraq. London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq. 69: 43–51.

- Curtis, J.E.; Collon, D (1996). "Ladies of Easy Virtue". In H. Gasche; Barthel Hrouda. Collectanea Orientalia: Histoire, Arts de l'Espace, et Industrie de la Terre. Civilisations du Proche-Orient: Series 1 - Archéologie et Environment. CDPOAE 3. Recherches et Publications. pp. 89–95. ISBN 2-940032-09-2.

- Davis, Frank (13 June 1936). "A puzzling "Venus" of 2000 B.C.: a fine Sumerian relief in London". The Illustrated London News. 1936 (5069): 1047.

- Frankfort, Henri (1937). "The Burney Relief". Archiv für Orientforschung. 12: 128–135.

- Gadd, C. J. (1933). "Epic of Gilgamesh, Tablet XII". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'Archéologie Orientale. XXX: 127–143.

- Jacobsen, Thorkild (1987). "Pictures and pictorial language (the Burney Relief)". In Mindlin, M.; Geller, M.J.; Wansbrough, J.E. Figurative Language in the Ancient Near East. London: School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. pp. 1–11. ISBN 0-7286-0141-9.

- Kaelin, Oskar (2006). "Modell Ägypten" Adoption von Innovationen im Mesopotamien des 3. Jahrtausends v. Chr. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis, Series Archaeologica (in German). 26. Fribourg: Academic Press Fribourg. ISBN 978-3-7278-1552-2.

- Kraeling, Emil G. (1937). "A Unique Babylonian Relief". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 67: 16–18. doi:10.2307/3218905.

- McCown, Donald E.; Haines, Richard C.; Hansen, Donald P. (1978). Nippur I, Temple of Enlil, Scribal Quarter, and Soundings. Oriental Institute Publications. LXXXVII. Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. pp. pl. 142:8, 142:10. ISBN 978-0-226-55688-8.

- Opitz, Dieter (1936). "Die vogelfüssige Göttin auf den Löwen". Archiv für Orientforschung (in German). 11: 350–353.

- Ornan, Tallay (2005). The Triumph of the Symbol: Pictorial Representation of Deities in Mesopotamia and the Biblical Image Ban. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis. 213. Fribourg: Academic Press Fribourg. ISBN 3-7278-1519-1.

- Patai, Raphael (1990). The Hebrew Goddess (3d ed.). Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-2271-9.

- Porada, Edith (1980). "The Iconography of Death in Mesopotamia in the early Second Millennium B.C.". In Alster, Bernd. Death in Mesopotamia, Papers read at the XXVIe Rencontre assyriologique internationale. Mesopotamia, Copenhagen Studis in Assyriology. 8. Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag. pp. 259–270. ISBN 87-500-1946-5.

- Spycket, Agnès (1968). Les Statues de Culte Dans les Textes Mesopotamiens des Origines A La Ire Dynastie de Babylon. Cahiers de la Revue Biblique (in French). 9. Paris: J. Gabalda.

- Thompson, William R. (2004). "Complexity, Diminishing Marginal Returns and Serial Mesopotamian Fragmentation" (PDF). Journal of World Systems Research. 28 (3): 613–652. ISSN 1076-156X. PMID 15517490. doi:10.1007/s00268-004-7605-z. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2009.

- Van Buren, Elizabeth Douglas (1936). "A further note on the terra-cotta relief". Archiv für Orientforschung. 11: 354–357.

- Von der Osten-Sacken, Elisabeth (2002). "Zur Göttin auf dem Burneyrelief". In Parpola, Simo; Whiting, Robert. M. Sex and Gender in the Ancient Near East. Proceedings of the XLVIIe Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Helsinki (in German). 2. Helsinki: The Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project. pp. 479–487. ISBN 951-45-9054-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Burney relief, Queen of the Night. |

- The Queen of The Night (ME 2003-7-18,1 at the British Museum)

- Nude Winged Goddess (AO 6501 at the Louvre)

- "Ishtar Vase" from Larsa (AO 17000 at the Louvre)

- This article is about an item held in the British Museum. The object reference is Loan 1238 / Registration:2003,0718.1.