Bunjevci

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| (Unknown; those in Serbia declaring themselves either as Bunjevci or Croats) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Serbia | 16,706 (2011 census) |

| Hungary | c. 1,500 (2001 census) |

| Languages | |

| Serbo-Croatian (Bunjevac dialect) | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholicism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other South Slavs | |

Bunjevci (Serbo-Croatian pronunciation: [bǔɲeːʋtsi], [bǔːɲeːʋtsi]) are a South Slavic ethnic group living mostly in the Bačka region of Serbia (province of Vojvodina) and southern Hungary (Bács-Kiskun county, particularly in the Baja region). They presumably originate from western Herzegovina, from where they migrated to Dalmatia, and from there to Lika and Bačka in the 16th and 17th century. Bunjevci who remained in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as those in modern Croatia, today maintain that designation chiefly as an ethno-regional identity, and often declare themselves as Croats.

Bunjevci are Roman Catholic, and speak a Croatian dialect with Ikavian pronunciation and with certain archaic characteristics. During the 18th and 19th century, they formed a sizable part of the population of northern Bačka, but many of them were gradually assimilated into Hungarians.

Ethnology

The Bunjevci are a South Slavic ethnic group, Catholic by religion, and Shtokavian-Ikavian by dialect, of which majority live in the Bačka region in Serbia and Bács-Kiskun county in Hungary.

Ethnonym

There are several theories about the origin of their name. The most common is that the name derives from the river Buna in central Herzegovina, their hypothesised ancestral homeland before their migrations. This etymology was first proposed by Fr. Marijan Lanosović and supported by Vuk Karadžić, Rudolf Horvat, Ivan Ivanić, Ivan Antonović, István Iványi, and Mijo Mandić. Another theory is that the name comes from the term Bunja, a traditional stone house in Dalmatia.

Their endonym, used in Serbo-Croatian, is Bunjevci (pronounced Serbo-Croatian pronunciation: [bǔɲeʋtsi]).[1] In Hungarian their name is bunyevácok, while in German Bunjewatzen.

Origin theories

Disputes over the national status of the Bunjevci go back to the nationalism wave in the 19th century in Austria-Hungary, but their "national status" remained ambiguous since, the debate revived by the Breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s.[2] It has been argued that they are Croats, Serbs, and yet another among the South Slavic nations.[2] The most common view is that the community fled western Herzegovina and Dalmatia to Vojvodina during the 17th-century Ottoman invasion, led by Franciscan monks, and were accepted in the Military Frontier.[3] The Catholic Church in Subotica celebrates 1686 as the anniversary of the Bunjevci migration, when the largest single migration did take place.[3] Croatian cultural historian Ante Sekulić, who himself belongs to the community, asserts that they were Slavicized Vlachs that converted to Catholicism.[3]

Demographics

Serbia

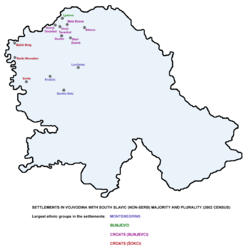

In Serbia, Bunjevci live in Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, mostly in the northern part of Bačka region. The community, however, has been divided around the issue of the ethnic affiliation: in the 2011 census, in terms of ethnicity, 16,706 inhabitants of Vojvodina self-declared as Bunjevci and 47,033 as Croats. Not all of the Croats in Vojvodina have Bunjevac roots; the other big group are Šokci.

The largest concentration of Bunjevci in Serbia (9,235) is in the ethnically mixed city of Subotica, which is their cultural and political centre. Another significant urban center of Bunjevac people is the city of Sombor (1,629). Villages with significant population of Bunjevci are all located in the administrative area of the city of Subotica:

Hungary

Towns and villages in Hungary with a significant population of Bunjevci (names of settlements in the Bunjevac dialect listed in brackets):

Villages which were partially populated by significant populations of Bunjevci in the past, but today have less than 70 Bunjevci villagers each:

- Csávoly (Čavolj)

- Felsőszentiván (Gornji Sveti Ivan, Gornji Sentivan)

- Bácsalmás (Aljmaš)

- Csikéria (Čikerija)

- Bácsbokod (Bikić)

- Mátételke (Matević)

- Vaskút (Baškut, Vaškut)

History

Early Modern Period and Austro-Hungarian Empire

According to one theory, Bunjevci settled in the city of Subotica and its surroundings in 1526.[4] According to another theory, they migrated to Bačka from Dalmatia (Zadar hinterland, Ravni Kotari, Cetinska krajina), Lika, Podgorje (littoral Bunjevci: Senj, Jablanac, Krivi Put, Krasno...) and western Herzegovina (area around river Buna, Čitluk, Međugorje)[5] in several groups led by Franciscan monks, to serve as mercenaries against Ottoman army in 1682, 1686, and 1687.[6] Historic documents refer to Bunjevci with various names.

In 1788 the first Austrian population census was conducted – it called Bunjevci Illyrians and their language the Illyrian language. It listed 17,043 Illyrians in Subotica. In 1850 the Austrian census listed them under Dalmatians and counted 13,894 Dalmatians in the city. Despite this, they traditionally called themselves Bunjevci. The Austro-Hungarian censuses from 1869 onward to 1910 numbered the Bunjevci distinctly. They were referred to as "bunyevácok" or "dalmátok" (in the 1890 census). In 1880 the Austro-Hungarian authorities listed in Subotica a total of 26,637 Bunjevci and 31,824 in 1892.

In 1910, 35.29% of population of the Subotica city (or 33,390 people) were registered as "others"; these people were mainly Bunjevci. In 1921 Bunjevci were registered by the Royal Yugoslav authorities as speakers of Serbian or Croatian language – Subotica city had 60,699 speakers of Serbian or Croatian or 66.73% of the total city population. Allegedly, 44,999 or 49.47% were Bunjevci. In the 1931 population census of the Royal Yugoslav authorities, 43,832 or 44.29% of the total Subotica population were Bunjevci.

It is estimated that a few tens of thousands of Bunjevci were Magyarized in the 19th and early 20th century. Croat national identity was adopted by some Bunjevci in the late 19th and early 20th century, especially by the majority of the Bunjevac clergy, notably one of the titular bishops of Kalocsa Ivan Antunović (1815–1888) supported the notion of calling Bunjevci and Šokci with the name Croats.

1880 saw the founding of the Bunjevačka stranka ("the Bunjevac party"), an indigenous political party. During this time, opinions varied on whether the Bunjevci should try to assert themselves as Croats or as an independent ethnic group.

Yugoslavia

In October 1918, Bunjevci held a national convention in Subotica and decided to secede Banat, Bačka and Baranja from the Kingdom of Hungary and to join Kingdom of Serbia. This was confirmed at the Great National Assembly of Serbs, Bunjevci and other Slavs in Novi Sad, which proclaimed unification with the Kingdom of Serbia in November 1918. The subsequent creation of the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (renamed Yugoslavia in 1929) brought most of the Bačka Bunjevci in the same country with the Croats (with some remaining in Hungary).

During the late World War II, Partisan General Božidar Maslarić spoke on the national councils in Sombor and Subotica on 6 November 1944 and General Ivan Rukavina on Christmas in Tavankut in the name of the Communist Party about the Croatdom of the Bunjevci. After 1945, in SFR Yugoslavia the census of 1948 did not officially recognize the Bunjevci (nor Šokci), and instead merged their data with the Croats, even if a person would self-declare as a Bunjevac or Šokac. The Yugoslav communist government counted Bunjevci (and Šokci) as part of Croatian national corpus. Proponents of a distinct Bunjevac ethnicity regard this time as another dark period of encroachment on their identity, and feel that this assimilation did not help in the preservation of their language. The censuses of 1953 and 1961 also listed all declared Bunjevci as Croats. The 1971 population census listed the Bunjevci separately under the municipal census in Subotica upon the personal request of the organization of Bunjevci in Subotica. It listed 14,892 Bunjevci or 10.15% of the population of Subotica. Despite this, the provincial and federal authorities listed the Bunjevci as Croats, together with the Šokci and considered them that way officially at all occasions. In 1981 the Bunjevci made a similar request – it showed 8,895 Bunjevci, or 5.7% of the total population of Subotica.

Contemporary period

Serbia

Following the breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, Bunjevac nationality was officially recognized as a minority group in Serbia in 1990. They were granted the status of autochthonous people in 1996.[7]

In the administrative area of city of Subotica region, there were 13,553 Bunjevci and 14,151 in 2011. The historically Bunjevac village of Donji Tavankut had 1,234 Croats, 787 Bunjevci, 190 Serbs and 137 declared as Yugoslavs. A 1996 survey by the local government in Subotica found that in the community, there are many people who declare as Croats and consider themselves Bunjevci, but also some people who declare as Bunjevci but consider themselves part of the wider Croatian nation. The same survey found that the delineation between the pro-Croat and pro-Bunjevac positions correlated with the delineation between the people who were more supportive towards the then ruling regime in Serbia that did not favor special rights for national minorities, and conversely those who were against the then government and more interested in minority rights and connections with what they saw as their second homeland.[8]

In early 2005, the Bunjevac issue was again popularized when the Vojvodina government decided to allow the official use of "bunjevački language with elements of national culture" in schools in the following school year – the Štokavian dialect with ikavian pronunciation. This was protested by the Croatian Bunjevac community as an attempt of the government to widen the rift between the two Bunjevac communities. They favour integration, regardless of whether some people declared themselves distinct, because minority rights (such as the right to use a minority language) are applied based on the number of members of the minority. As opposed to this, supporters of pro-Bunjevci option are accusing Croats for attempts to assimilate Bunjevci.[9] In 2011, Bunjevac politician Blaško Gabrić and Bunjevac National Council asked Serbian authorities to start juristic criminal responsibility procedure against those Croats who denying the existence of Bunjevci ethnicity, which is, according to them, violation of laws and constitution of the Republic of Serbia.[9]

Today, both major parts of the community (the pro-independent Bunjevac one and the pro-Croatian one) continue to consider themselves ethnologically as Bunjevci, although each subscribing to its interpretation of the term.

Hungary

In Hungary, Bunjevci are not officially recognized as a minority; the government simply consider them Croats. In April 2006 a Bunjevci group began collecting subscriptions to register Bunjevci as a distinct minority group. In Hungary, 1,000 valid subscriptions are needed to register an ethnic minority with historical presence. By the end of the given 60 days period the initiative gained over 2,000 subscriptions of which cca. 1,700 were declared valid by national vote office and Budapest parliament gained a deadline of 9 January 2007 to solve the situation by approving or refusing the proposal. No other such initiative has reached that level ever since minority bill passed in 1992.[10] On 18 December the National Assembly of Hungary refused to accept the initiative (with 334 No and 18 Yes votes). The decision was based on the study of the Hungarian Academy of Science that denied the existence of an independent Bunjevac minority (they stated that Bunjevci are a Croatian subgroup). The opposition of Croatian minority leaders also played part in the outcome of the vote,[11] and the opinion of Hungarian Academy of Sciences.[12]

Culture

Cultural centre of Bunjevci from Bačka is the city of Subotica. Cultural centre of littoral Bunjevci is the city of Senj. Traditionally, Bunjevci of Bačka are associated with land and farming. Large, usually isolated farms in Northern Bačka called salaši are a significant part of their identity. Most of their customs celebrate the land, harvest, horse-breeding, and their most important feasts (other than Christmas and weddings) are:

- Dužijanca – celebration of harvest end, and the most famous festival as well as a tourist attraction. It consists of several events held in Bunjevci-populated places (Bajmok, Donji Tavankut, Gornji Tavankut), with the central celebration held in Subotica. Dužijanca includes religious celebrations devoted to harvest, street procession and performing of Bunjevci folklore and music.

- Krsno ime – a celebration of a patron saint of the family.

- Kraljice – ceremonial processions held on Pentecost.

- Divan – a meeting of young boys and girls for singing and dancing in a place afar from their parents. The custom has been forbidden by church authorities already in mid-19th century.

Bunjevačke novine ("Bunjevac newspaper") is the main newspaper in Bunjevac dialect, published in Subotica.

Notable people

| Part of a series on |

| Croats |

|---|

|

|

Subgroups |

- Gaja Alaga (1924–1988), theoretical physicist

- Ivan Antunović (1815–1888), writer and bishop

- Zvonko Bogdan, singer of traditional music

- Mara Đorđević-Malagurski (1894–1971), writer and ethnographer

- Antun Gustav Matoš (1873–1914), Croatian writer

- Ivan Gutman (1947-), chemist and mathematician

- Obádovics J. Gyula (b. 1927), Hungarian professor of mathematics

- Blaško Rajić (1878–1951), priest and writer

- Ivan Sarić (1876–1966), aviation pioneer and athlete

- Mirko Vidaković (1924–2002), botanist and member of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts

See also

References

- ↑ "Bunjevci". Hrvatski jezični portal.

- 1 2 Todosijević 2002, p. 1.

- 1 2 3 Todosijević 2002, p. 3.

- ↑ Szabadka varos története, II. Rész. 1892. of István Iványi

- ↑ Radio Subotica Bunjevci posjetili svoju pradomovinu, Sep 24, 2008

- ↑ Todosijević, Bojan (2002), "Why Bunjevci did not Become a Nation: A Case Study" (PDF), East Central Europe, 29 (1-2): 59–72

- ↑ "Bunjevci – to be granted status of people". Politika. 1996-10-01. Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- ↑ Todosijević, Bojan (2002). "Why Bunjevci did not Become a Nation: A Case Study" (PDF). East Central Europe. 29 (1-2). pp. 59–72.

- 1 2 http://www.pravda.rs/2011/02/16/srbija-progoni-bunjevce/

- ↑ Nemzetiségi elismerést a bunyevácoknak – Index Fórum

- ↑ Iromány adatai

- ↑ "Hrvatski glasnik br.3" (PDF). Odbijena narodna inicijativa... , Jan 18, 2007 (714KB)(in Croatian)

Sources

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Further reading

- Beckett, Weaver Eric (2011). "Hungarian views of the Bunjevci in Habsburg times and the inter-war period". Balcanica. 42: 77–115.

- Mandić, Mijo (2009). "Buni, bunievci, bunjevci". Bunjevačka matica. (in Croatian)

- Šarić, Marko (2008). "Bunjevci u ranome novom vijeku. Postanak i razvoj jedne predmoderne etnije". Živjeti na Krivom putu. Zagreb: FF Press: 15–43. (in Croatian)

- Sekulić, Ante (1989). Bački bunjevci i šokci. Školska knj. (in Croatian)

- Skenderović, Robert (2012). "The formation of the political identity of the Bunjevci during the second half of the 19th century". Časopis za suvremenu povijest. 44 (1): 137–160. (in Croatian)

- Todosijević, Bojan (2002). "Why Bunjevci did not become a nation: A case study" (PDF). East Central Europe. 29 (1-2): 59–72. (in Serbian)

- Vukić, Aleksandar; Bara, Mario (2013). "The Importance of Observation, Classification and Description in the Construction of the Ethnic Identity of Bunjevci from Bačka (1851–1910)". Dve domovini. 37: 69–81. (in Croatian)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bunjevci. |

- Bunjevci.com

- Bunjevci HKPD Matija Gubec Tavankut

- (in Croatian) Hrvatska revija br. 3/2005. Proslava 250. obljetnice doseljavanja veće skupine Bunjevaca (1686.-1936.) – Bunjevci u jugoslavenskoj državi

- (in Croatian) HIC Međunarodni znanstveni skup "Jugoistočna Europa 1918.-1995."

- The Croatian Bunjevci

- (in Croatian) Bunjevci in Senj (Croatia)

- Ivan Ivanić: O Bunjevcima (Subotica, 1894)

- (in Croatian) www.bunjevac.com – Bunjevac Dubravko Kopilović – Vinkovci – Hrvatska – Croatia (Vinkovci, 2008)

- Representations of Bunjevci in Hungary