Buggery Act 1533

|

| |

| Long title | An Acte for the punishment of the vice of Buggerie |

|---|---|

| Citation | 25 Hen. 8 c. 6 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repealed by | Offences against the Person Act 1828 (9 Geo. 4 c. 31) |

Status: Repealed | |

The Buggery Act 1533, formally An Acte for the punishment of the vice of Buggerie (25 Hen. 8 c. 6), was an Act of the Parliament of England that was passed during the reign of Henry VIII.

It was the country's first civil sodomy law, such offences having previously been dealt with by the ecclesiastical courts.

The Act defined buggery as an unnatural sexual act against the will of God and man. This was later defined by the courts to include only anal penetration and bestiality.[2] The Act remained in force until it was repealed and replaced by the Offences against the Person Act 1828, and buggery would remain a capital offence until 1861.

Description

The Act was piloted through Parliament by Henry VIII's minister Thomas Cromwell and punished "the detestable and abominable Vice of Buggery committed with Mankind or Beast". "Buggery" was not further defined in the law.[3] According to the Act:

the offenders being hereof convicted by verdict confession or outlawry shall suffer such pains of death and losses and penalties of their good chattels debts lands tenements and hereditaments as felons do according to the Common Laws of this Realm. And that no person offending in any such offence shall be admitted to his Clergy ...[4]

This meant that a convicted sodomite’s possessions could be confiscated by the government, rather than going to their next of kin, and that even priests and monks could be executed for the offence—even though they could not be executed for murder.[4] Henry later used the law to execute monks and nuns (thanks to information his spies had gathered) and take their monastery lands—the same tactics had been used 200 years before by Philip IV of France against the Knights Templar. Henry may have had this in mind when he drafted the Act.[5]

In July 1540 Walter Hungerford, 1st Baron Hungerford of Heytesbury was charged with treason for harbouring a known member of the Pilgrimage of Grace movement. Although he had been married three times, and had four children, he was also accused of buggery. Hungerford was beheaded at Tower Hill[6] (as he was not hanged it suggests the accusations of buggery were for purposes of humiliation), on 28 July 1540, the same day as Thomas Cromwell.[6]

Nicholas Udall, a cleric, playwright, and Headmaster of Eton College, was the first to be charged with violation of the Act alone in 1541, for sexually abusing his pupils. In his case, the sentence was commuted to imprisonment and he was released in less than a year. He went on to become headmaster of Westminster School.

16th century repeal and re-enactment

The Act was repealed in 1553 on the accession of Queen Mary. However, it was re-enacted by Queen Elizabeth I in 1563. Although "homosexual prosecutions throughout the sixteenth century [were] sparse" and "fewer than a dozen prosecutions are recorded up through 1660 ... this may reflect inadequate research into the subject, and a scarcity of extant legal records."[7] In 1631 Mervyn Tuchet, 2nd Earl of Castlehaven was beheaded because of his rank. Numerous prosecutions that resulted in a sentence of hanging are recorded in the 18th and early 19th centuries.[8]

Even if the charge of sodomy was reduced for lack of evidence to a charge of attempted buggery, the penalty was severe: imprisonment and some time on the pillory. "The lesser punishment—to be stood in the pillory—was by no means a lenient one, for the victims often had to fear for their lives at the hands of an enraged multitude armed with brickbats as well as filth and curses ... the victims in the pillory, male or female, found themselves at the centre of an orgy of brutality and mass hysteria, especially if the victim were a molly."[9][10]

Periodicals of the time sometimes casually named known sodomites, and at one point even suggested that sodomy was increasingly popular. This does not imply that sodomites necessarily lived in security.

In Rex v Samuel Jacobs (1817), it was concluded that fellatio between an adult man and an underage boy was not punishable under this Act.[11] The courts had previously established, in Rex v Richard Wiseman in 1716, that heterosexual sodomy was considered buggery under the meaning of the 1533 Act.[12]

In light of R v Jacobs, fellatio thus remained legal until the passage of Labouchere Amendment in 1885, which added the charge of gross indecency to the traditional term of sodomy.

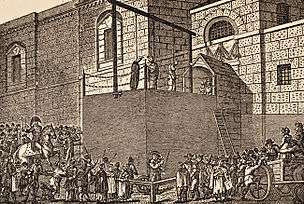

The last two Englishmen who were hanged for sodomy were executed in 1835, when James Pratt and John Smith died in front of the Newgate Prison in London on 27 November.[13][14]

Repeal in 1828

The Act was repealed by section 1 of the Offences against the Person Act 1828 (9 Geo.4 c.31) and by section 125 of the Criminal Law (India) Act 1828 (c.74). It was replaced by section 15 of the Offences against the Person Act 1828, and section 63 of the Criminal Law (India) Act 1828, which provided that buggery would continue to be a capital offence. The new Act expressly specified that conviction of buggery no longer required proof of completion ("emission of seed") and evidence of penetration was sufficient for conviction.[15]

Buggery remained a capital offence in England and Wales until the enactment of the Offences against the Person Act 1861.

The United Kingdom Parliament repealed buggery laws for England and Wales in 1967 (in so far as they related to consensual homosexual acts in private), ten years after the Wolfenden report. Legal statutes in many former colonies have retained them, such as in the Anglophone Caribbean.

See also

- Timeline of LGBT history

- LGBT rights in the United Kingdom

- LGBT rights in the Commonwealth of Nations

Notable convictions under the Act:

- John Atherton, Bishop of Waterford, 1640

- Vere Street Coterie, 1810

- Percy Jocelyn, Bishop of Clogher, 1822

References

- ↑ This is only a conventional short title for this Act.

- ↑ R v Jacobs (1817) Russ & Ry 331 confirmed that buggery related only to intercourse per anum by a man with a man or woman, or intercourse per anum or per vaginam by either a man or a woman with an animal. Other forms of "unnatural intercourse" may amount to indecent assault or gross indecency, but do not constitute buggery (see generally: Smith & Hogan, Criminal Law (10th ed.) ISBN 0-406-94801-1)

- ↑ Raithby, John (ed.) (1811). The Statutes at Large, of England and Great Britain. 3. London: Eyre and Strahan. p. 145.

- 1 2 "Reflections on BNA, part 6: British Law". The Drummer's Revenge. 25 July 2007. Retrieved 3 February 2010.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ Crompton, Louis (2003-01-01). Homosexuality and Civilization. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03006-0.

- 1 2 "Walter Hungerford and the ‘Buggery Act’ | English Heritage". www.english-heritage.org.uk. Retrieved 2017-03-20.

- ↑ Norton, Rictor. "5 The Medieval Basis of Modern Law". A History of Homophobia. Gay History and Literature.

- ↑ Norton, Rictor. "Homosexuality in Eighteenth-Century England". Gay History and Literature.

- ↑ Norton, Rictor. "Popular Rage (Homophobia)". Homosexuality in Eighteenth-Century England. Gay History and Literature.

- ↑ Gilbert, Creighton (1995). Caravaggio and his two cardinals. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-271-01312-1.

- ↑ Sir William Oldnall Russell (1825). Crown Cases Reserved for Consideration: And Decided by the Twelve Judges of England, from the Year 1799 to the Year 1824. p. 331.

- ↑ "Another Kind of Love "d0e1110"". publishing.cdlib.org.

- ↑ "A history of London's Newgate prison". www.capitalpunishmentuk.org.

- ↑ Alternative date April 8, 1835, See "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-11-20. Retrieved 2012-08-01. seen 2012

- ↑ 9 Geo.4 c.31, section XVIII

External links

- The law in England, 1290–1885, concerning homosexual conduct

- Michael Kirby, "The sodomy offence: England's least lovely criminal law export?", Journal of Commonwealth Criminal Law, I 2011, pp. 22–43.

- Full text of the act, from The statutes at large, of England and of Great Britain (1811) Nb

.svg.png)