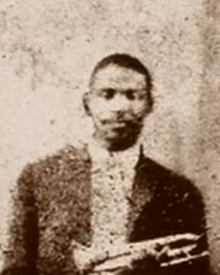

Buddy Bolden

| Buddy Bolden | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Charles Joseph Bolden |

| Born |

September 6, 1877 New Orleans |

| Died |

November 4, 1931 (aged 54) Jackson, Louisiana |

| Genres | Jazz, blues |

| Occupation(s) | Musician |

| Instruments | Cornet |

Charles Joseph "Buddy" Bolden (September 6, 1877 – November 4, 1931) was an African-American cornetist who was regarded by contemporaries as a key figure in the development of a New Orleans style of rag-time music, or "jass", which later came to be known as jazz.

Life

Family and early life

Buddy Bolden's father, Westmore Bolden, was working as a "driver" for the family of his grandfather's (Gustavus Bolden, died 1866) former master or boss, one William Walker, when Buddy Bolden was born, and his mother was Alice née Harris, who was aged 18 when they married on August 14, 1873 (and his father, at the time, must have been around 25 years old, as he was recorded as being 19 years old in August 1866). Buddy Bolden's father died when he was six, and young Bolden continued to live with his mother and family members afterwards.[1] In documents of the period the family name is spelled at different times as "Bolen", "Bolding", "Boldan", and "Bolden", thus hampering research.[2] He likely went to Fisk School in New Orleans, but evidence for this is circumstantial, as, in the area where he lived, early records of this school and other schools are missing.[3]

Further life and legend

While there is substantial first hand oral history about Buddy Bolden, facts about his life continue to be lost amidst colorful myth. Stories about his being a barber by trade or that he published a scandal sheet called The Cricket have been repeated in print despite being debunked decades earlier.[4]

Musical career and early decline

He was known as King Bolden (see Jazz royalty), and his band was popular in New Orleans (the city of his birth) from about 1900 until 1907, when he was incapacitated by schizophrenia (then called dementia praecox). Bolden was known for his loud sound and improvisation. He made a big impression on younger musicians. While Bolden's trombonist Willie Cornish among others recalled making phonograph cylinder recordings with the Bolden band, no surviving copy has ever been found.[5]

Bolden suffered an episode of acute alcoholic psychosis in 1907 at the age of 30. With the full diagnosis of dementia praecox, he was admitted to the Louisiana State Insane Asylum at Jackson, a mental institution, where he spent the rest of his life.[6][7]

Bolden was buried in an unmarked grave in Holt Cemetery, a pauper's graveyard in New Orleans. In 1998, a monument to Bolden was erected in Holt Cemetery, but his exact gravesite remains unknown.

Music

Many early jazz musicians credited Bolden and the members of his band with being the originators of what came to be known as "jazz", though the term was not in common musical use until after the era of Bolden's prominence. At least one writer has labeled him the father of jazz.[8] He is credited with creating a looser, more improvised version of ragtime and adding blues to it; Bolden's band was said to be the first to have brass instruments play the blues. He was also said to have taken ideas from gospel music heard in uptown African-American Baptist churches.

Instead of imitating other cornetists, Bolden played music he heard "by ear" and adapted it to his horn. In doing so, he created an exciting and novel fusion of ragtime, black sacred music, marching-band music, and rural blues. He rearranged the typical New Orleans dance band of the time to better accommodate the blues; string instruments became the rhythm section, and the front-line instruments were clarinets, trombones, and Bolden's cornet. Bolden was known for his powerful, loud, "wide open" playing style.[6] Joe "King" Oliver, Freddie Keppard, Bunk Johnson, and other early New Orleans jazz musicians were directly inspired by his playing.

No known recordings of Bolden have survived. His trombonist Willy Cornish asserted that Bolden's band had made at least one phonograph cylinder in the late 1890s. Three other old-time New Orleans musicians, George Baquet, Alphonse Picou and Bob Lyons also remembered a recording session ("Turkey in the Straw", according to Baquet) in the early 1900s. The researcher Tim Brooks believes that these cylinders, if they existed, may have been privately recorded for local music dealers and were never distributed in bulk.

Some of the songs first associated with his band, such as the traditional song "Careless Love" and "My Bucket's Got a Hole in It", are still standards. Bolden often closed his shows with the original number "Get Out of Here and Go Home", although for more "polite" gigs, the last number would be "Home! Sweet Home!".

"Funky"

One of the most famous Bolden numbers is a song called "Funky Butt" (known later as "Buddy Bolden's Blues"), which represents one of the earliest references to the concept of "funk" in popular music, now a musical subgenre. Bolden's "Funky Butt" was, as Danny Barker once put it, a reference to the olfactory effect of an auditorium packed full of sweaty people "dancing close together and belly rubbing."[7] Other musicians closer to Bolden's generation explained that the famous tune originated as a reference to flatulence.

I thought I heard Buddy Bolden say,

Funky-butt, funky-butt, take it away.

The "Funky Butt" song was one of many in the Bolden repertory with rude or off-color lyrics popular in some of the rougher places where he played, and Bolden's trombonist Willy Cornish claimed authorship. It became so well known as a rude song that even whistling the melody on a public street was considered offensive. The melody was incorporated into the early published ragtime number "St. Louis Tickle."

Big four

Bolden is also credited with the invention of the "Big Four", a key rhythmic innovation on the marching band beat, which gave embryonic jazz much more room for individual improvisation. As Wynton Marsalis explains,[9] the Big Four (below) was the first syncopated bass drum pattern to deviate from the standard on-the-beat march.[10] The second half of the Big Four is the pattern commonly known as the hambone Rhythm developed from sub-Saharan African music traditions.

Tributes to Bolden

Music

- Sidney Bechet wrote and composed "Buddy Bolden Stomp" in his honor.

- Duke Ellington paid tribute to Bolden in his 1957 suite A Drum Is a Woman. The trumpet part was taken by Clark Terry.

- The Bolden band tune "Funky Butt", better known as "Buddy Bolden's Blues" since it was first recorded under that title by Jelly Roll Morton, alternatively titled "I Thought I Heard Buddy Bolden Say," has been covered by hundreds of artists, including Dr. John on his Goin' Back to New Orleans and Hugh Laurie on his record Let Them Talk.

- "Hey, Buddy Bolden" is a song on the album, Nina Simone Sings Ellington.

- Wynton Marsalis speaks about Bolden in an introduction, and performs "Buddy Bolden" on his album Live at the Village Vanguard.

Fiction

Bolden has inspired a number of fictional characters with his name.

- The Canadian author Michael Ondaatje wrote a novel Coming Through Slaughter, which features a "Buddy Bolden" character who in some ways resembles Bolden, but in other ways is deliberately contrary to what is known about him.

- The character of Buddy Bolden helps Samuel Clemens solve a murder in Peter J. Heck's novel, A Connecticut Yankee in Criminal Court (1996).

- Bolden is featured as a prominent character in David Fulmer's murder mystery entitled Chasing the Devil's Tail,[12] where he is a bandleader and a suspect in the murders. He also appears by reputation or in person in Fulmer's other books.

- He is a notable character in Louis Maistros' novel The Sound of Building Coffins,[13] which contains many scenes depicting Bolden playing his cornet.

- In Tiger Rag, Nicholas Christopher tells the story of Bolden and the lost cylinders he recorded with his group.

Plays and films

- Bolden is featured in August Wilson's play Seven Guitars. Wilson's drama includes the character King Hedley, whose father named him after King Buddy Bolden. King Hedley constantly sings, "I thought I heard Buddy Bolden say..." and believes that Bolden will come down and bring him money to buy a plantation.

- Wilson's King Hedley II continues the story of Seven Guitars, and also refers to Bolden.

- A biopic about Bolden, titled Bolden!, was released in 2015. Gary Carr portrays Bolden.[14]

- In 2011, Interact Theater in Minneapolis created a new musical theater piece entitled Hot Jazz at da Funky Butt in which Buddy Bolden was the feature character. Music and Lyrics were composed by Aaron Gabriel and featured the New Orleans Band "Rue Fiya". The song "Dat's How Da Music Do Ya" featured the Buddy Bolden Blues.

References

- ↑ Donald M. Marquis: In Search of Buddy Bolden, p. 11-18.

- ↑ Donald M. Marquis: In Search of Buddy Bolden, p. 19

- ↑ Donald M. Marquis: In Search of Buddy Bolden, p. 29-30

- ↑ see Donald M. Marquis: In Search of Buddy Bolden, p. 58 and p. 92 where Marquis states: "In asking questions about Bolden, if the barbershop, the Cricket, girls, loudness, and "Funky Butt" are all that is mentioned, one can surmise that rather than actually having known Bolden the person has merely read Jazzman." (that is the, as Marquis proves, rather inaccurate account given by Charles Edward Smith and Frederic Ramsay Jr., the editors of the book in question (see Marquis, p. 3 - 4))

- ↑ see Donald M. Marquis: In Search of Buddy Bolden, p.107: "... on that fabled cylinder, according to Willie Cornish, they [Buddy Bolden's band] had recorded a couple of marches." In the 2005 epilogue to the book (p.158-159) Marquis also discusses these recordings that have not been found. On pages 44-45 of the same book the question is discussed in detail. Marquis concludes: "That the cylinder was made is quite believable; that it is gone forever is even more believable..." (p. 44)

- 1 2 Barlow, William. "Looking Up At Down": The Emergence of Blues Culture. Temple University Press (1989), pp. 188-91. ISBN 0-87722-583-4.

- 1 2 "Two Films Unveil a Lost Jazz Legend". National Public Radio. December 15, 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-14.

By most accounts, a mix of alcohol and mental illness sent Bolden into an asylum in 1907; he stayed there until his death in 1931.

- ↑ Ted Gioia, The History of Jazz, Oxford/New York, 1997, p. 34

- ↑ "What is the Big Four beat? - Jazz & More". Jazz.nuvvo.com. 2008-11-24. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2013-09-20.

- ↑ Marsalis, Wynton (2000: DVD n.1). Jazz. PBS.

- ↑ "Jazz and Math: Rhythmic Innovations", PBS.org. The Wikipedia example shown in half time compared to the source.

- ↑ "CDTPraise". Davidfulmer.com. Retrieved 2013-09-20.

- ↑ "Welcome". Louis Maistros. Retrieved 2013-09-20.

- ↑ Fleming Jr, Mike (28 May 2014). "Seven Years After Production Began, Dan Pritzker's 'Bolden' Skeds New Shoot, Sans Star Anthony Mackie". Deadline.com. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

Further reading

- Barker, Danny, 1998, Buddy Bolden and the Last Days of Storyville. New York: Continuum. p. 31.

- Marquis, Donald. In Search Of Buddy Bolden: First Man Of Jazz. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-3093-1.

External links

- Buddy Bolden at DMOZ

- Buddy Bolden on National Public Radio

- Bolden! on IMDb

- Buddy Bolden's New Orleans Music

- "Charles "Buddy" Bolden, RedHotJazz.com, Biography with suggested reading

- Buddy Bolden Biography, PBS, Jazz, A Film by Ken Burns

- Buddy Bolden at Find a Grave