Vihara

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

Vihara (विहार, vihāra) is the Sanskrit and Pali term for a Buddhist monastery. It originally meant "a secluded place in which to walk", and referred to "dwellings" or "refuges" used by wandering monks during the rainy season.

The northern Indian state of Bihar derives its name from the word "vihara", due to the abundance of Buddhist monasteries in that area. The word "vihara" has also been borrowed in Malay where it is spelled "biara," and denotes a monastery or other non-Muslim place of worship. In Thailand and China (called jingshe; Chinese: 精舎), "vihara" has a narrower meaning, and designates a small shrine hall or retreat house. It is called a "Wihan" (วิหาร) in Thai, and a "Vihear" in Khmer. In Burmese, wihara (ဝိဟာရ, IPA: [wḭhəɹa̰]), means "monastery," but the native Burmese word kyaung (ကျောင်း, IPA: [tɕáʊɴ]) is preferred. Monks wandering from place to place preaching and seeking alms often stayed together in the sangha.

Origins

In the early decades of Buddhism the wandering monks of the Sangha, dedicated to asceticism and the monastic life, had no fixed abode. During the rainy season (cf. vassa) they stayed in temporary shelters. These dwellings were simple wooden constructions or thatched bamboo huts. However, as it was considered an act of merit not only to feed a monk but also to shelter him, sumptuous monasteries were created by rich lay devotees (Mitra 1971). They were located near settlements, close enough for begging alms from the population but with enough seclusion to not disturb meditation.

Trade-routes were therefore ideal locations for a vihara and donations from wealthy traders increased their economic strength. From the first century CE onwards viharas also developed into educational institutions, due to the increasing demands for teaching in Mahayana Buddhism (Chakrabarti 1995).

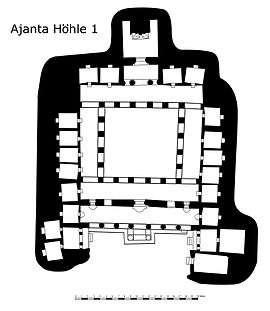

In the second century BCE a standard plan for a vihara was established. It could be either structural, which was more common in the south of India, or rock-cut like the chaitya-grihas of the Deccan. It consisted of a walled quadrangular court, flanked by small cells. The front wall was pierced by a door, the side facing it in later periods often incorporated a shrine for the image of the Buddha. The cells were fitted with rock-cut platforms for beds and pillows (Mitra 1971). The unwanted rock was excavated, leaving the carved cave structure.[1] This basic layout was still similar to that of the communal space of an ashrama ringed with huts in the early decades of Buddhism (Tadgell 1990).

As permanent monasteries became established, the name "Vihara" was kept. Some Viharas became extremely important institutions, some of them evolving into major Buddhist Universities with thousands of students, such as Nalanda.

Life in "Viharas" was codified early on. It is the object of a part of the Pali canon, the Vinaya Pitaka or "basket of monastic discipline".

Buddhist Vihara or monastery is an important form of institution associated with Buddhism. It may be defined as a residence for monks, a centre for religious work and meditation and a centre of Buddhist learning. Reference to five kinds of dwellings (Pancha Lenani) namely, Vihara, Addayoga, Pasada, Hammiya and Guha is found in the Buddhist canonical texts as fit for monks. Of these only the Vihara (monastery) and Guha (Cave) have survived.

In Punjabi, an open space inside a home is also called 'vehra'.

History

The earliest Buddhist rock-cut cave abodes and sacred places (chaiti) are found in the western Deccan dating back to the 3rd century BC.[2] These earliest rock-cut caves include the Bhaja Caves, the Karla Caves, and some of the Ajanta Caves. Relics found in these caves suggest an important connection between the religious and the commercial, as Buddhist missionaries often accompanied traders on the busy international trading routes through India. Some of the cave viharas and chaityas, commissioned by wealthy traders, included pillars, arches, reliefs and facades while trade boomed between the Roman Empire and south-east Asia.[3][4]

Epigraphic, literary and archaeological evidence testify to the existence of many Buddhist Viharas in Bengal (West Bengal and Bangladesh) and Bihar from the 5th century AD to the end of the 12th century. These monasteries were generally designed in the old traditional Kushana pattern, a square block formed by four rows of cells along the four sides of an inner courtyard. They were usually built of stone or brick. As the monastic organization developed, they became elaborate brick structures with many adjuncts.

Often they consisted of several stories and along the inner courtyard there usually ran a veranda supported on pillars. In some of them a stupa or shrine with a dais appeared. Within the shrine stood the icon of Buddha, Bodhisattva or Buddhist female deities. More or less the same plan was followed in building monastic establishments in Bengal and Bihar during the Gupta and Pala Empire period. In course of time monasteries became important centres of learning. At the age of Mauryan emperor Ashoka the great the Mahabodhi Temple was built in the form of vihara.

An idea of the plan and structure of some of the flourishing monasteries may be found from the account of Xuanzang, who referred to the grand monastery of Po-si-po, situated about 6.5 km west of the capital city of Pundravardhana (Mahasthan). The monastery was famous for its spacious halls and tall chambers. General Cunningham identified this vihara with bhasu vihara. Huen-tsang also noticed the famous Lo-to-mo-chi vihara (Raktamrittika Mahavihara) near Karnasuvarna (Rangamati, Murshidabad, West Bengal). The site of the monastery has been identified at Rangamati (modern Chiruti, Murshidabad, West Bengal). A number of smaller monastic blocks arranged on a regular plan, with other adjuncts, like shrines, stupas, pavilions etc. have been excavated from the site.

One of the earliest viharas in Bengal was located at Biharail (Rajshahi district, Bangladesh). The plan of the monastery was designed on an ancient pattern, i.e. rows of cells round a central courtyard. The date of the monastery may be ascribed to the Gupta period.

As the Buddhist ideology encouraged identification with trade, monastic complexes became stopovers for inland traders and provided lodging houses that were usually located near trade routes. As their mercantile and royal endowments grew, cave interiors became more elaborate with interior walls decorated with beautiful paintings exquisite reliefs and intricate carvings.[3] Elaborate facades were added to the exteriors as the interiors became designated for specific uses as monasteries (viharas) and worship halls (chaityas). Over the centuries simple caves began to resemble three-dimensional buildings, formally designed and requiring highly skilled artisans and craftsmen to complete as in the Ellora Caves. The highly skilled artisans never forgot their timber roots and imitated the nuances of a wooden structure and the wood grain.[5]

Mahaviharas of the Pāla era

A range of monasteries grew up during the Pāla period in ancient Magadha (modern Bihar) and Bengal. According to Tibetan sources, five great Mahaviharas stood out: Vikramashila, the premier university of the era; Nalanda, past its prime but still illustrious, Somapura, Odantapurā, and Jaggadala.[6] The five monasteries formed a network; "all of them were under state supervision" and there existed "a system of co-ordination among them . . it seems from the evidence that the different seats of Buddhist learning that functioned in eastern India under the Pāla were regarded together as forming a network, an interlinked group of institutions," and it was common for great scholars to move easily from position to position among them.[7]

Other notable monasteries of Pala period were Traikuta, Devikota (identified with ancient kotivarsa, 'modern Bangarh'), and Pandita vihara. Excavations jointly conducted by Archaeological Survey of India and University of Burdwan in 1971-1972 to 1974-1975 yielded a Buddhist monastic complex at Monorampur, near Bharatpur via Panagarh Bazar in the Burdwan district of West Bengal. The date of the monastery may be ascribed to the early medieval period. Recent excavations at Jagjivanpur (Malda district, West Bengal) revealed another Buddhist monastery (Nandadirghika-Udranga Mahavihara)[8] of the ninth century.

Nothing of the superstructure has survived. A number of monastic cells facing a rectangular courtyard have been found. A notable feature is the presence of circular corner cells. It is believed that the general layout of the monastic complex at Jagjivanpur is by and large similar to that of Nalanda. Beside these, scattered references to some monasteries are found in epigraphic and other sources. Among them Pullahari (in western Magadha), Halud vihara (45 km south of Paharpur), Parikramana vihara and Yashovarmapura vihara (in Bihar) deserve mention.

Other important structural complexes have been discovered at Mainamati (Comilla district, Bangladesh). Remains of quite a few viharas have been unearthed here and the most elaborate is the Shalvan Vihara. The complex consists of a fairly large vihara of the usual plan of four ranges of monastic cells round a central court, with a temple in cruciform plan situated in the centre. According to a legend on a seal (discovered at the site) the founder of the monastery was Bhavadeva, a ruler of the Deva dynasty.

Image gallery

Vihara at Kanheri Caves

Vihara at Kanheri Caves Wall carvings at Kanheri Caves

Wall carvings at Kanheri Caves Simple slab abode beds in vihara at Kanheri Caves

Simple slab abode beds in vihara at Kanheri Caves Main vihara at Kanheri Caves

Main vihara at Kanheri Caves

See also

- Brahma-vihara

- Kanheri Caves

- List of Buddhist temples

- Nava Vihara

- Wat - a Buddhist temple in Cambodia, Laos or Thailand.

- Gompa

Notes

- ↑ "Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent - Glossary". Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- ↑ Thapar, Binda (2004). Introduction to Indian Architecture. Singapore: Periplus Editions. p. 34. ISBN 0-7946-0011-5.

- 1 2 Keay, John (2000). India: A History. New York: Grove Press. pp. 124–127. ISBN 0-8021-3797-0.

- ↑ "Entrance at Ajanta". Retrieved 2007-03-21.

- ↑ "Entrance Cave 9, Ajanta". art-and-archaeology.com. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- ↑ English, Elizabeth (2002). Vajrayogini: Her Visualization, Rituals, and Forms. Wisdom Publications. p. 15. ISBN 0-86171-329-X.

- ↑ Dutt, Sukumar (1962). Buddhist Monks And Monasteries Of India: Their History And Contribution To Indian Culture. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd. pp. 352–3. OCLC 372316.

- ↑ "Jagjivanpur, A newly discovered Buddhist site in west Bengal". Information & Cultural Affairs Department, Government of West Bengal. Archived from the original on August 9, 2009.

References

- Chakrabarti, Dilip K. (October 1995). "Buddhist Sites across South Asia as Influenced by Political and Economic Forces". World Archaeology. 27 (2): 185–202. JSTOR 125081. doi:10.1080/00438243.1995.9980303.

- Mitra, D. (1971). Buddhist Monuments. Calcutta: Sahitya Samsad. ISBN 0-89684-490-0.

- Tadgell, C. (1990). The History of Architecture in India: From the Dawn of Civilization to the End of the Raj. London: Phaidon. ISBN 1-85454-350-4.

- Khettry, Sarita (2006). Buddhism in North-Western India: Up to C. A.D. 650. Kolkata: R.N. Bhattacharya. ISBN 978-81-87661-57-3.

- Rajan, K.V. Soundara (1998). Rock-cut Temple Styles: Early Pandyan Art and The Ellora Shrines. Mumbai: Somaiya Publications. ISBN 81-7039-218-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Buddhist monasteries. |

- Lay Buddhist Practice: The Rains Residence - A short article on the meaning of Vassa, and its observation by lay Buddhists.

- Mapping Buddhist Monasteries A project aiming to catalogue, crosscheck, verify and interrelate, tag and georeference, chronoreference and, finally, map online (using KML markup & Google Maps technology).