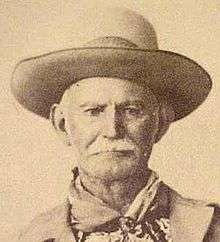

Brushy Bill Roberts

| Brushy Bill Roberts | |

|---|---|

Brushy Bill | |

| Born | Unknown |

| Died |

December 27, 1950 Hico, Texas, U.S. |

| Nationality | United States of America |

| Other names |

William H. Bonney (alias Billy the Kid, allegedly) Oliver Partridge Roberts Oliver L. Roberts |

| Occupation | Prospector |

Brushy Bill Roberts (? – December 27, 1950; claimed date of birth December 31, 1859) a.k.a. William Henry Roberts [1], Ollie Partridge William Roberts, Ollie P. Roberts or Ollie L. Roberts, attracted attention by claiming to be the western outlaw William H. Bonney, also known as Billy the Kid. Roberts' claim was rejected by Governor Thomas Mabry in 1950 and has been widely debated since that time. Brushy Bill's story is promoted by the "Billy the Kid Museum" in his hometown of Hico in Hamilton County, Texas. [2] His claim was further promoted by the 1990 film Young Guns II, as well as a 2011 episode of Brad Meltzer's Decoded on the History Channel. Robert Stack did a segment on Brushy Bill in early 1990 on the NBC television series Unsolved Mysteries and more recently it was promoted by former television personality Bill O'Reilly.

Background

In 1948, a lawyer named William Morrison[3] located an elderly man named Joe Hines, who had requested the lands of his deceased brother. Hines had confessed that he was the outlaw Jesse Evans, who had vanished from public view after getting released from a Texas prison in 1882. Hines told Morrison of his experiences in the Lincoln County War with Billy the Kid, who had been killed by Sheriff Pat Garrett on July 14, 1881. Hines surprised Morrison by claiming that the Kid was still alive and living near Hamilton, Texas under the name Ollie P. Roberts (nicknamed "Brushy Bill").

Morrison then began a correspondence with Roberts, who eventually "confessed" to being the Kid, and detailed his supposed exploits as an outlaw. He told anecdotes that if true would fill in undocumented gaps in many aspects of the life of Billy the Kid, and asked for Morrison's help in acquiring the full pardon he said he had been promised by New Mexico Governor Lew Wallace in 1879 but then had been refused. He showed his ability to slip out of handcuffs,[4] and said that Garrett had actually shot and killed another gunslinger named Billy Barlow and had passed his body off as the Kid's, which had allowed the Kid to vanish and escape to Mexico.[5]

Roberts told Morrison that he would agree to tell the "whole truth" in exchange for the full pardon he had been promised by Wallace following the Lincoln County War. His sudden appearance and request for a pardon had a profound effect on Garrett's descendants. Brushy Bill claimed to have been born William Henry Roberts in Buffalo Gap, Texas, near Abilene, on December 31, 1859 and claimed to have taken the identity of Oliver P. Roberts around 1910. Detractors of Roberts point to the fact that a family bible family Bible belonging to Oliver Roberts' niece, Geneva Pittmon, (Oliver P. Roberts, not Oliver L.) showed that O.P. Roberts was born in 1879. [6] Because Billy the Kid was 21 at the time of his death in 1881, if Brushy Bill Roberts was born Oliver P. Roberts, then it would be impossible for him to have been the Kid. Supporters of Roberts maintain that the birth date of the real Oliver P. Roberts' would have no relevance to a man who assumed his identity later in life.

It is worthy of note that if Brushy Bill had been born in 1859, he would have been ninety at the time of his death from a massive heart attack in Hico, Texas. Had he been born in 1879, he would have been only seventy-one at the time of his death. In addition, Roberts had allegedly claimed to be a member of Jesse James' gang, before deciding to come out as the "true" Billy the Kid.[7] In January 1950, Brushy Bill claimed he was a member of the James–Younger Gang as a teenager and identified J. Frank Dalton as Jesse James.[8]

Morrison vouchsafed that upon examination of Robert's stripped body, he showed every scar that Billy the Kid reputedly had, and more.[4][9] Morrison also attempted to track down former Evans Gang member Jim McDaniels, and located him in Round Rock, Texas. McDaniels, along with Severo Gallegos, Martile Able[10][11] and Jose Montoya, all of whom had known Billy the Kid, signed affidavits verifying their belief that Roberts was in fact Billy the Kid. Bill and Sam Jones declined to sign such affidavits, Sam Jones begging off with the statement, "Received your letter, and am sorry but feel that I can't sign your affidavit. I'm old and I just don't feel like being obligated so...", and Bill Jones' grandson expressing doubts about the veracity of Roberts' claims in a letter of refusal written on his grandfather's behalf.[12] The Kid was fluent in spoken Spanish and could read and write English proficiently (his letters to Governor Lew Wallace seeking a pardon still survive), but the question of whether or not Brushy Bill was even literate is still unsettled.

Brushy and his story were largely forgotten until the movie Young Guns II depicted him as the narrator of events surrounding the life and times of Billy The Kid and the Lincoln County War. More books were written on the mystery and researchers began exploring whether Brushy’s claim might have actually been true, including several failed attempts to obtain permission for exhumation and DNA testing.

Numerous books have been published since 1950 examining Brushy's claim, the first of which was Alias Billy the Kid, written by Morrison and the western historian C.L. Sonnichsen. This book received mixed reviews at the time but did win support from former President Harry S. Truman, who wrote to Morrison indicating he believed that Brushy was Billy the Kid and lamenting that he died before being able to go in front of the next governor, where he may have gotten a more favorable result. In 2005, W.C. Jameson, himself a student of C.L. Sonnichsen, re-examined the subject and released Billy the Kid: Beyond the Grave. Jameson's work led to increased interest in Robert's story and led to additional interest and study, most notably that of former Lincoln County Deputy Sheriff and Mayor of Capitan, NM Steve Sederwall. In April 2015, media personality Bill O'Reilly weighed in on the topic by publishing his book Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Liars: The Real West in which he suggests that the evidence in favor of Brushy Bill Roberts outweighs the accepted version of history, citing the original Alias Billy the Kid book by Morrison and Sonnichsen.[13] O'Reilly followed up his book with an episode on the subject during his national television broadcast purportedly depicting the events that occurred during the alleged killing of the Kid from Brushy Bill's perspective.

Photograph

In 1989 the Lincoln County Heritage Trust commissioned a computer study by forensic anthropologist Clyde Snow. Scanned photographs of Billy the Kid and Roberts, along with those of 150 other people, were fed into a computer utilising a "similarity index" to match 25 facial "landmarks". This resulted in Roberts' photo ranking 42nd (i.e.: 41 other people more closely resembled the tintype than Roberts). Snow indicated that if the two were the same person, then Roberts should have ranked at least 2nd. It was noted that the accuracy of facial comparisons are dependent on the position of the face in the photographs being the same.[14]

In 1990, a study using photo comparison equipment at the Laboratory for Vision Studies and the Advanced Graphic Laboratory in the University of Texas was conducted by image-experts Scott Acton and Alan Bovik. The study corrected for the facial positioning and used the same face recognition techniques used by the FBI, CIA and Interpol which are claimed to provide a "significant level of statistical validity". Photographs of Brushy Bill Roberts at age fourteen seemed to resemble the well known Dedrick-Upham tintype of Billy The Kid. A photograph of Brushy Bill at age 71 was a 93% match. Both Acton and Bovik concluded that this result "irrefutably shows that Roberts and the Kid are a very close match". However, these findings would have to be replicated to be scientifically conclusive (which to date has not occurred), and in that case would still not prove that Roberts and Billy the Kid were the same person. In 1996 the results of the study were presented to Andre McNeil, chancery judge of the 12th judicial district, and a prominent Arkansas attorney, Helen Grinder, who stated that based on the study and other evidence the case for Roberts being Billy the Kid was "strong", "substantial", and "excellent".[15]

DNA

In 2003 Lincoln County Sheriff Tom Sullivan, Capitan, New Mexico Mayor Steve Sederwall, and De Baca County, New Mexico Sheriff Gary Graves began a campaign to exhume the remains of Billy the Kid and his mother, Catherine Antrim, to prove through DNA analysis that it was in fact Billy the Kid buried in Fort Sumner . The initiative hit snags from the beginning. First, there is no confirmation as to where the remains are located. Second were the legalities, with both pro-Brushy Bill Roberts and anti-Brushy Bill Roberts experts protesting the exhumation. The exhumation of both sets of remains was blocked in court in September 2004.

- Problems with DNA testing

- The Fort Sumner Cemetery where Billy the Kid was said to have been buried was washed out by the Great Pecos River Flood in 1904. The damage was so great that exposed remains had to be reburied with most being unidentified. Billy's headstone had been washed away and his grave remained unmarked for 28 years. Although a headstone was erected in 1932 it is unknown where the original grave was.

- The Silver City cemetery where Catherine Antrim was buried was sold in 1882 with the new owner required to relocate the graves outside the city limits. There is no record to indicate whether the bodies were moved or just the headstones. It is possible that other people had been buried in the same grave. It is possible that she had been originally buried in an unmarked grave with the headstone placed by guesswork later.

- Considering the length of time since burial it is likely any remains have decomposed completely and there is a negligible chance of positively identifying remains if any are found.

- Roberts claimed Catherine Antrim was not his mother but an aunt related by marriage so a DNA test would be meaningless in any scenario other than Catherine and Billy's remains both being identified, tested and shown to be mother and son.

Hico, Texas

At the time of his death, Brushy Bill lived on West 2nd Street in Hico. He was buried in the county seat of Hamilton, twenty miles south of Hico. Despite the discrepancies noted above, the Hico Chamber of Commerce has capitalized on his claim by opening the "Billy the Kid Museum" in the historic Western section of Hico.[16] In the downtown is a marker devoted to Brushy Bill: "Ollie L. 'Brushy Bill' Roberts, alias Billy the Kid, died in Hico, Texas, December 27, 1950. He spent the last days of his life trying to prove to the world his true identity and obtain the pardon promised him by the governor of the state of New Mexico (Lew Wallace). We believe his story and pray to God for the forgiveness he solemnly asked for."[17]

| Billy the Kid in Hico | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

See also

- American Folklore

- The Authentic Life of Billy, the Kid

- Cowboy

- List of American Old West outlaws

- List of Western lawmen

- Mention in Billy the Kid article

References

- ↑

- ↑ Moreno, Eric. "The Old Man Who Claimed to Be Billy the Kid". Atlas Obscura. Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ↑ Joyce Gibson Roach (June 1979). C. L. Sonnichsen. Boise State University. p. 18.

- 1 2 Cara Mae Coe Marable Smith (1988). The Coes Go West: From Billy the Kid Land to Movie and Other Entertainment Lands. Complete Print., Incorporated. p. 55.

- ↑ Dale L. Walker (15 November 1998). Legends and Lies: Great Mysteries of the American West. MacMillan. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-312-86848-2.

- ↑ "Book Talk". 23–30. Albuquerque, N.M.: New Mexico Book League. 1994: v. ISSN 0145-627X. OCLC 2258493. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ↑ Gene Fowler (1 March 2008). Mavericks: A Gallery of Texas Characters. University of Texas Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-292-71819-7.

- ↑ "Jesse Wants His "True" Name; Asks Court For Official Rule". The Times Recorder. Zanesville, Ohio. January 10, 1950. Retrieved 2017-07-22.

- ↑ Charles L. Sonnichsen (1955). Alias Billy the Kid. University of New Mexico Press. p. 19.

- ↑ Dale L. Walker (15 November 1998). Legends and Lies: Great Mysteries of the American West. MacMillan. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-0-312-86848-2.

- ↑ Gene Fowler (1 March 2008). Mavericks: A Gallery of Texas Characters. University of Texas Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-292-71819-7.

- ↑ Charles L. Sonnichsen (1955). Alias Billy the Kid. University of New Mexico Press. p. 113.

William Shafer, Bill Jones' grandson, wrote on July 9, 1950: "I am sorry, but Mr. Jones does not feel that he can sign your affidavits that your man is Billy the Kid. He gave no conclusive proof of this at the time we met him. It seems to me that if he were Billy the Kid he would not need affidavits to prove his contention."

- ↑ David Fisher; Bill O'Reilly (7 April 2015). Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies: The Real West. Henry Holt and Company. p. 399. ISBN 978-1-62779-508-1.

- ↑ Joe Nickell (10 June 2005). Camera Clues: A Handbook for Photographic Investigation. University Press of Kentucky. p. 89. ISBN 0-8131-9124-6.

- ↑ W. C. Jameson (7 August 2008). Billy the Kid: Beyond the Grave. Taylor Trade Publishing. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-58979-403-0.

- ↑ Texas Department of Transportation, Texas State Travel Guide, 2008, pp. 200-201

- ↑ Roberts historical marker, Hico, Texas