Bronze Age Europe

| European Bronze Age | |

|---|---|

| |

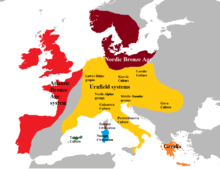

The European Bronze Age is characterized by bronze artifacts and the use of bronze implements. The regional Bronze Age succeeds the Neolithic. It starts with the Aegean Bronze Age in 3200 BC[1] (succeeded by the Beaker culture), and spans the entire 2nd millennium BC (Unetice culture, Tumulus culture, Terramare culture, Urnfield culture and Lusatian culture) in Northern Europe, lasting until c. 600 BC.

History

Aegean

The Aegean Bronze Age begins around 3200 BC[1] when civilizations first established a far-ranging trade network. This network imported tin and charcoal to Cyprus, where copper was mined and alloyed with the tin to produce bronze. Bronze objects were then exported far and wide, and supported the trade. Isotopic analysis of the tin in some Mediterranean bronze objects indicates it came from as far away as Great Britain.

Knowledge of navigation was well developed at this time, and reached a peak of skill not exceeded until a method was discovered (or perhaps rediscovered) to determine longitude around AD 1750, with the notable exception of the Polynesian sailors.

The Minoan civilization based from Knossos, Crete, appears to have coordinated and defended its Bronze Age trade. One crucial lack in this period was that modern methods of accounting were not available. The eruption of Thera, which according to archaeological data occurred in c. 1500 BC, resulted in the decline of the Minoan.[2] This turn of events gave the opportunity to the Mycenaeans to spread their influence throughout the Aegean. Around c. 1450 BC, they were in control of Crete itself and colonized several other Aegean islands, reaching as far as Rhodes.[3] Thus the Mycenaeans became the dominant power of the region, marking the beginning of the Mycenaean 'Koine' era (from Greek: Κοινή, common), a highly uniform culture that spread in mainland Greece and the Aegean.[4] The Mycenaean Greeks introduced several innovations in the fields of engineering, architecture and military infrastructure, while trade over vast areas of the Mediterranean was essential for the Mycenaean economy. Their syllabic script, the Linear B, offers the first written records of the Greek language and their religion already included several deities that can be also found in the Olympic Pantheon. Mycenaean Greece was dominated by a warrior elite society and consisted of a network of palace states that developed rigid hierarchical, political, social and economic systems. At the head of this societies was the king, known as wanax.[5]

Caucasus

The Maykop culture was the major early Bronze Age culture in the North Caucasus. Some scholars date arsenical bronze artifacts in the region as far back as the mid-4th millennium BC.[6]

Eastern Europe

The Yamna culture[7] was a late copper age/early Bronze Age culture dating to the 36th–23rd centuries BC. The culture was predominantly nomadic, with some agriculture practiced near rivers and a few hill-forts.

The Catacomb culture, covering several related archaeological cultures, was first to introduce corded pottery decorations into the steppes and showed a profuse use of the polished battle axe, providing a link to the West. Parallels with the Afanasevo culture, including provoked cranial deformations, provide a link to the East. It was preceded by the Yamna culture and succeeded by the western Corded Ware culture. The Catacomb culture in the Pontic steppe was succeeded by the Srubna culture from c. the 17th century BC.

Central Europe

| European Bronze Age finds | |

|---|---|

| |

Important sites include:

In Central Europe, the early Bronze Age Unetice culture (1800–1600 BC) includes numerous smaller groups like the Straubingen, Adlerberg and Hatvan cultures. Some very rich burials, such as the one located at Leubingen (today part of Sömmerda) with grave gifts crafted from gold, point to an increase of social stratification already present in the Unetice culture. All in all, cemeteries of this period are rare and of small size. The Unetice culture is followed by the middle Bronze Age (1600–1200 BC) Tumulus culture, which is characterised by inhumation burials in tumuli (barrows). In the eastern Hungarian Körös tributaries, the early Bronze Age first saw the introduction of the Makó culture, followed by the Otomani and Gyulavarsánd cultures.

The late Bronze Age Urnfield culture (1300–700 BC) is characterized by cremation burials. It includes the Lusatian culture in eastern Germany and Poland (1300-500 BC) that continues into the Iron Age. The Central European Bronze Age is followed by the Iron Age Hallstatt culture (700-450 BC).

Northern Europe

In northern Germany, Denmark, Sweden and Norway, Bronze Age cultures manufactured many distinctive and artistic artifacts. This includes lur horns, horned ceremonial helmets, sun discs, gold jewellery and some unexplained finds like the bronze "gong" from Balkåkra in Sweden. Some linguists believe that an early Indo-European language was introduced to the area probably around 2000 BC, which eventually became Proto-Germanic, the last common ancestor of the Germanic languages. This would fit with the apparently unbroken evolution of the Nordic Bronze Age into the most probably ethnolinguistically Germanic Pre-Roman Iron Age.

The age is divided into the periods I-VI, according to Oscar Montelius. Period Montelius V, already belongs to the Iron Age in other regions.

Britain

In Great Britain, the Bronze Age is considered to have been the period from around 2100 to 700 BC. Immigration brought new people to the islands from the continent. Recent tooth enamel isotope research on bodies found in early Bronze Age graves around Stonehenge indicate that at least some of the immigrants came from the area of modern Switzerland. The Beaker people displayed different behaviours from the earlier Neolithic people and cultural change was significant. Integration is thought to have been peaceful as many of the early henge sites were seemingly adopted by the newcomers. The rich Wessex culture developed in southern Britain at this time. Additionally, the climate was deteriorating; where once the weather was warm and dry it became much wetter as the Bronze Age continued, forcing the population away from easily defended sites in the hills and into the fertile valleys. Large livestock ranches developed in the lowlands which appear to have contributed to economic growth and inspired increasing forest clearances. The Deverel-Rimbury culture began to emerge in the second half of the 'Middle Bronze Age' (c. 1400–1100 BC) to exploit these conditions. Cornwall was a major source of tin for much of western Europe and copper was extracted from sites such as the Great Orme mine in northern Wales. Social groups appear to have been tribal but with growing complexity and hierarchies becoming apparent.

Also, the burial of dead (which until this period had usually been communal) became more individual. For example, whereas in the Neolithic a large chambered cairn or long barrow was used to house the dead, the 'Early Bronze Age' saw people buried in individual barrows (also commonly known and marked on modern British Ordnance Survey maps as Tumuli), or sometimes in cists covered with cairns.

The greatest quantities of bronze objects found in England were discovered in East Cambridgeshire, where the most important finds were done in Isleham (more than 6500 pieces).[8]

Ireland

The Bronze Age in Ireland commenced in the centuries around 2000 BC when copper was alloyed with tin and used to manufacture Ballybeg type flat axes and associated metalwork. The preceding period is known as the Copper Age and is characterised by the production of flat axes, daggers, halberds and awls in copper. The period is divided into three phases: Early Bronze Age 2000-1500 BC; Middle Bronze Age 1500-1200 BC and Late Bronze Age 1200-c. 500 BC. Ireland is also known for a relatively large number of Early Bronze Age Burials.[9] [10]

See also

- Chariot burial

- Megalithic tomb

- Old European hydronymy

- Helladic period

- Nordic Bronze Age

- Atlantic Bronze Age

References

- 1 2 "Ancient Greece". British Museum. Retrieved 2015-05-06.

- ↑ Chadwick, John (1976). The Mycenaean World. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 12. ISBN 0-521-29037-6..

- ↑ Tartaron, Thomas F. (2013). Maritime Networks in the Mycenaean World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 28. ISBN 9781107067134..

- ↑ Schofield, Louise (2006). The Mycenaeans. Los Angeles, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum. p. 75. ISBN 9780892368679..

- ↑ Castleden, Rodney (2005). The Mycenaeans. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 2, 228–235. ISBN 0-415-36336-5.

- ↑ Douglas Q. Adams (January 1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. pp. 372–374. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5.

- ↑ Also known as Pit Grave culture or Ochre Grave culture

- ↑ Hall, David (1994). Fenland survey : an essay in landscape and persistence / David Hall and John Coles. London; English Heritage. ISBN 1-85074-477-7., p. 81-88

- ↑ Waddell, J. 1998. The Prehistoric Archaeology of Ireland. Galway.

- ↑ Eogan, G. 1983. The Hoards of the Irish Later Bronze Age. Dublin