Broiler

| |

| Distribution | World-wide |

|---|---|

| Use | meat |

| Traits | |

| Skin color | Yellow |

| Classification | |

| Notes | |

| Hybrid varieties, not a breed | |

| |

Broiler chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus), or broilers, are a gallinaceous domesticated fowl, bred and raised specifically for meat production.[1] They are a hybrid of the egg-laying chicken, both being a subspecies of the red junglefowl (Gallus gallus). Typical broilers have white feathers and yellowish skin. Most commercial broilers reach slaughter-weight at between five and seven weeks of age, although slower growing breeds reach slaughter-weight at approximately 14 weeks of age. Because the meat broilers are this young at slaughter, their behaviour and physiology are that of an immature bird. Due to artificial selection for rapid early growth and the husbandry used to sustain this, broilers are susceptible to several welfare concerns, particularly skeletal malformation and dysfunction, skin and eye lesions, and congestive heart conditions. The breeding stock (broiler-breeders) grow to maturity and beyond but also have welfare issues related to the frustration of a high feeding motivation and beak trimming. Broilers are usually grown as mixed-sex flocks in large sheds under intensive conditions, but some breeds can be grown as free-range flocks. Chickens are one of the most common and widespread domestic animals.[2]

Origins and domestication

The domestic chicken is descended primarily from the red junglefowl (Gallus gallus) and is classified as a sub-species (Gallus gallus domesticus) of that species. As such, it can and does freely interbreed with populations of red jungle fowl.[3]

The traditional poultry farming view is stated in Encyclopædia Britannica (2007): "Humans first domesticated chickens of Indian origin for the purpose of cockfighting in Asia, Africa, and Europe. Very little formal attention was given to egg or meat production... ".[4]

Genetic studies point to multiple maternal origins, with the clade found in the Americas, Europe, Middle East, and Africa, originating from the Indian subcontinent, where a large number of unique haplotypes occur.[5][6] It is postulated that the jungle fowl, known as the "bamboo fowl" in many Southeast Asian languages, is a pheasant well adapted to take advantage of the large amounts of fruits that are produced during the end of the 50 year bamboo seeding cycle to boost its own reproduction.[7] It has been suggested that in domesticating the chicken, humans took advantage of this prolific reproduction of the jungle fowl when exposed to a large amount of food.[8] Similarly, it is speculated that the flexibility and adaptability inherited from the chicken's red junglefowl ancestor allows them to cope with the "unnatural and intense conditions" of modern production.[9]

Recent genetic analysis has revealed that at least the gene for yellow skin was incorporated into domestic birds through hybridization with the grey junglefowl (G. sonneratii).[10]

Modern breeding

Before the development of modern commercial meat breeds (chickens, etc.), broilers were mostly young male chickens culled from farm flocks. Pedigree breeding began around 1916.[11] Magazines for the poultry industry existed at this time.[11][12] A hybrid variety of chicken was produced from a cross of a male of a naturally double-breasted Cornish strain and a female of a tall, large-boned strain of white Plymouth Rocks.[13] This first attempt at a hybrid meat breed was introduced in the 1930s and became dominant in the 1960s. The original hybrid was plagued by problems of low fertility, slow growth and disease susceptibility.

Modern broilers have become very different from the Cornish/Rock hybrid. As an example, Donald Shaver (originally a breeder of egg-layers) began gathering breeding stock for a broiler program in 1950. Besides the breeds normally favoured, Cornish Game, Plymouth Rock, New Hampshire, Langshans, Jersey Black Giant and Brahmas were included. A white feathered female line was purchased from Cobb. A full scale breeding program was commenced in 1958, with commercial shipments in Canada and the US in 1959 and in Europe in 1963.[14]

As a second example, colour sexing broilers was proposed by Shaver in 1973. The genetics were based on the company's breeding plan for egg-layers which had been developed in the mid-1960s. A difficulty facing the breeders of the colour-sexed broiler is that the chicken must be white-feathered by slaughter age. After 12 years, accurate colour sexing without compromising economic traits was achieved.[14]

Artificial insemination

Artificial insemination is a mechanism in which spermatozoa are deposited into the reproductive tract of a female.[15] Artificial insemination provides a number of benefits relating to reproduction in the poultry industry. Broiler breeds have been selected specifically for growth, causing them to develop large pectoral muscles, which interfere with and reduce natural mating.[16] The amount of sperm produced and deposited in the hen’s reproductive tract may be limited because of this. Additionally, the males overall sex drive may be significantly reduced due to growth selection.[17] Artificial insemination has also allowed many farmers to incorporate valuable genes into their stock, increasing their genetic quality [18]

Abdominal massage is the most common method used for semen collection.[16] During this process, the rooster is restrained and the back region located towards the tail and behind the wings is caressed. This is done gently but quickly. Within a short period of time, the male should get an erection of the phallus. Once this occurs, the cloaca is squeezed and semen is collected from the external papilla of the vas deferens [19]

During artificial insemination, semen is most frequently deposited intra-vaginally by means of a plastic syringe. In order for semen to be deposited here, the vaginal orifice is everted through the cloaca. This is simply done by applying pressure to the abdomen of the hen. The semen-containing instrument is placed 2–4 cm into the vaginal orifice. As the semen is being deposited, the pressure applied to the hen’s abdomen is being released simultaneously.[16] The individual performing this procedure typically uses one hand to move and direct the tail feathers, while using the other hand to insert the instrument and semen into the vagina.[19]

General biology

Modern commercial broilers, for example, Cornish crosses and Cornish-Rocks, are artificially selected and bred for large-scale, efficient meat production and although they are the same species, grow much faster than egg laying hens or traditional dual purpose breeds. They are noted for having very fast growth rates, a high feed conversion ratio, and low levels of activity. Modern commercial broilers are bred to reach a slaughter-weight of about 2 kg in only 35 to 49 days.[13][20][21] Slow growing free-range and organic strains have been developed which reach slaughter-weight at 12 to 16 weeks of age. As a consequence, the behaviour and physiology of broilers reared for meat are those of immature birds, rather than adults.

Typical broilers have white feathers and yellowish skin. Recent genetic analysis has revealed that the gene for yellow skin was incorporated into domestic birds through hybridization with the grey junglefowl (G. sonneratii).[22] Modern crosses are also favorable for meat production because they lack the typical "hair" which many breeds have that necessitates singeing after plucking. Both male and female broilers are reared for their meat.

Behaviour

Because broiler chickens are the same species as egg laying hens, their behavioural repertoires are initially similar, and also similar to those of other gallinaceous birds. However, broiler behaviour is modified by the environment and alters as the broilers’ age and bodyweight rapidly increase. For example, the activity of broilers reared outdoors is initially greater than broilers reared indoors, but from six weeks of age, decreases to comparable levels in all groups.[23] The same study shows that in the outdoors group, surprisingly little use is made of the extra space and facilities such as perches – it was proposed that the main reason for this was leg weakness as 80 per cent of the birds had a detectable gait abnormality at seven weeks of age. There is no evidence of reduced motivation to extend the behavioural repertoire, as, for example, ground pecking remained at significantly higher levels in the outdoor groups because this behaviour could also be performed from a lying posture rather than standing.

Broiler breeders, i.e. males and females reared to fertilise and lay the eggs of the offspring reared for food, perform similar mating behaviour to other chicken types. They exhibit male-male aggression, male-hen aggression, hen-hen aggression, male waltzes, hen crouches, attempted hen mounts, completed hen mounts, attempted hen matings, and completed hen matings. These behaviours are seen less often and may not be exhibited as vigorously as observed in other chicken types.[24] Examining the frequency of all sexual behaviour shows a large decrease with age, suggestive of a decline in libido. The decline in libido is not enough to account for reduced fertility in heavy cocks at 58 weeks and is probably a consequence of the large bulk or the conformation of the males at this age interfering in some way with the transfer of semen during copulations which otherwise look normal.[25]

Physiology

Nociceptors which respond to noxious stimulation have been identified and physiologically characterised in many different part of the body of the chicken including the beak, mouth, nose, joint capsule and scaly skin. Stimulation of these nociceptors produces cardiovascular and behavioural changes consistent with those seen in mammals and are indicative of pain perception. Physiological and behavioural experiments have identified the problem of acute pain following beak trimming in chicks, shackling, and feather pecking and environmental pollution.[26]

Feeding and feed conversion

Chickens are omnivores and modern broilers are given access to a special diet of high protein feed, usually delivered via an automated feeding system. This is combined with artificial lighting conditions to stimulate eating and growth and thus the desired body weight.

In the U.S. in 2011, the average feed conversion ratio of a broiler was 1.91 pounds of feed per pound of liveweight. In 1925 the figure was 4.70.[27]

Canada has a typical FCR of 1.72.[28]

New Zealand commercial broiler farms have recorded the world's best broiler chicken FCR, consistently at 1.38 or lower.[29]

Welfare issues

Meat birds

Artificial selection has led to a great increase in the speed with which broilers develop and reach slaughter-weight. The time required to reach 1.5 kg live-weight decreased from 120 days to 30 days between 1925 and 2005. Selection for fast early growth-rate, and feeding and management procedures to support such growth, have led to various welfare problems in modern broiler strains.[30] Welfare of broilers is of particular concern given the large number of individuals that are produced; for example, the U.S. in 2011 produced approximately 9 billion broiler chickens.[31]

Cardiovascular dysfunction

Selection and husbandry for very fast growth means there is a genetically induced mismatch between the energy-supplying organs of the broiler and its energy-consuming organs.[21] Rapid growth can lead to metabolic disorders such as sudden death syndrome (SDS) and ascites.[30]

SDS is an acute heart failure disease that affects mainly male fast-growing broilers which appear to be in good condition. Affected birds suddenly start to flap their wings, lose their balance, sometimes cry out and then fall on their backs or sides and die, usually all within a minute. In 1993, U.K. broiler producers reported an incidence of 0.8%. In 2000, SDS has a death rate of 0.1% to 3% in Europe.[21]

Ascites is characterised by hypertrophy and dilatation of the heart, changes in liver function, pulmonary insufficiency, hypoxaemia and accumulation of large amounts of fluid in the abdominal cavity. Ascites develops gradually and the birds suffer for an extended period before they die. In the UK, up to 19 million broilers die in their sheds from heart failure each year.[32]

Skeletal dysfunction

Breeding for increased breast muscle means that the broilers’ centre of gravity has moved forward and their breasts are broader compared with their ancestors, which affects the way they walk and puts additional stresses on their hips and legs.[21] There is a high frequency of skeletal problems in broilers, mainly in the locomotory system, including varus and valgus deformities, osteodystrophy, dyschondroplasia and femoral head necrosis.[30] These leg abnormalities impair the locomotor abilities of the birds, and lame birds spend more time lying and sleeping.[33] The behavioural activities of broilers decrease rapidly from 14 days of age onwards.[34] Reduced locomotion also decreases ossification of the bones and results in skeletal abnormalities; these are reduced when broilers have been exercised under experimental conditions.[30]

Most broilers find walking painful, as indicated by studies using analgesic and anti-inflammatory drugs. In one experiment, healthy birds took 11 seconds to negotiate an obstacle course, whereas lame birds took 34 seconds. After the birds had been treated with carprofen, there was no effect on the speed of the healthy birds, however, the lame birds now took only 18 seconds to negotiate the course, indicating that the pain of lameness is relieved by the drug.[35] In self-selection experiments, lame birds select more drugged feed than non-lame birds[36] leading to the suggestion that leg problems in broilers are painful.

Several research groups have developed "gait scores" (GS) to objectively rank the walking ability and lameness of broilers. In one example of these scales, GS=0 indicates normal walking ability, GS=3 indicates an obvious gait abnormality which affects the bird’s ability to move about and GS=5 indicates a bird that cannot walk at all. GS=5 birds tried to use their wings to help them walking, or crawled along on their shanks. In one study, almost 26% of the birds examined were rated as GS=3 or above and can therefore be considered to have suffered from painful lameness.[21]

| “ | ...there is evidence that, far from improving, leg problems may have deteriorated further during the 1990s. Large and representative surveys of commercial broiler flocks in Denmark (1999) and Sweden (2002) found that in Denmark, 75% of the chickens had some walking abnormality and 30.1% were very lame (gait score greater than 2). In Sweden, over 72% of the chickens had some walking abnormality and around20% were very lame. 36.9% of the chickens surveyed in Denmark and around half (46.4% and 52.6%, depending on strain) of the chickens surveyed in Sweden had leg deformities (varus/valgus). 57% of the chickens surveyed in Denmark and around half of the chickens surveyed in Sweden showed some evidence of tibial dychondroplasia (Sanotra, Berg and Lund, 2003).[21] | ” |

The video recordings below are examples of broilers attempting to walk with increasing levels of gait abnormalities and therefore increasing gait scores.

- Gait score = 0

- Gait score = 1

- Gait score = 2

- Gait score = 3

- Gait score = 4

- Gait score = 5

Integument lesions

Sitting and lying behaviours in fast growing strains increase with age from 75% in the first seven days to 90% at 35 days of age. This increased inactivity is linked with an increase in dermatitis caused by a greater amount of time in contact with ammonia in the litter. This contact dermatitis is characterised by hyperkeratosis and necrosis of the epidermis at the affected sites; it can take forms such as hock burns, breast blisters and foot pad lesions.[30]

Stocking density

Broilers are usually kept at high stocking densities which vary considerably between countries. Typical stocking densities in Europe range between about 22 to 42 kg/m2 or between about 11 to 25 birds per square metre.[21] There is a reduction of feed intake and reduced growth rate when stocking density exceeds approximately 30 kg/m2 under deep litter conditions. The reduced growth rate is likely due to a reduced capacity to lose heat generated by metabolism. Higher stocking densities are associated with increased dermatitis including food pad lesions, breast blisters and soiled plumage.[30] In a large-scale experiment with commercial farms, it was shown that the management conditions (litter quality, temperature and humidity) were more important than stocking density.[37]

Ocular dysfunction

In attempts to improve or maintain fast growth, broilers are kept under a range of lighting conditions. These include continuous light (fluorescent and incandescent), continuous darkness, or under dim light; chickens kept under these light conditions develop eye abnormalities such as macrophthalmos, avian glaucoma, ocular enlargement and shallow anterior chambers.[38][39]

Ammonia

The litter in broiler pens can become highly polluted from the nitrogenous feces of the birds and produce ammonia. Ammonia has been shown to cause increased susceptibility to disease and other health-related problems such as Newcastle disease, airsaculitis and keratoconjunctivitis. The respiratory epithelium in birds is damaged by ammonia concentrations in the air exceeding 75 parts per million (ppm). Ammonia concentrations at 25 to 50 ppm induce eye lesions in broiler chicks after seven days of exposure.[39]

Catching and transport

Once the broilers have reached the target live-weight, they are caught, usually by hand, and packed live into crates for transport to the slaughterhouse. They are usually deprived of food and water for several hours before catching until slaughter. The process of catching, loading, transport and unloading causes serious stress, injury and even death to a large number of broilers.

The number of broilers that died in the EU in 2005 during the process of catching, packing and transport was estimated to be as high as 18 to 35 million. In the UK, of broilers that were found to be ‘dead on arrival’ at the slaughterhouse in 2005, it was estimated that up to 40% may have died from thermal stress or suffocation due to crowding on the transporter.[21]

Slaughter is done by hanging the birds fully conscious by their feet upside-down in shackles on a moving chain, stunning them by automatically immersing them in an electrified water bath and exsanguination by cutting their throats.

Some research indicates that chickens might be more intelligent than previously supposed, which "raises questions about how they are treated". A possible 10-year life span has been shortened to six weeks for broilers.[9]

Mortality rates

According to historic records, broiler mortality rates are decreasing. In 1925, the mortality rate in the U.S. was 18% compared to 3.8% in 2011.[27]

One indication of the effect of broilers' rapid growth rate on welfare is a comparison of the usual mortality rate for standard broiler chickens (1% per week) with that for slower-growing broiler chickens (0.25% per week) and with young laying hens (0.14% per week); the mortality rate of the fast-growing broilers is seven times the rate of laying hens (the same subspecies) of the same age.[21]

Parent birds

Meat broilers are usually slaughtered at approximately 35 to 49 days of age, well before they become sexually reproductive at 5 to 6 months of age. However, the bird's parents, often called "broiler-breeders", must live to maturity and beyond so they can be used for breeding. As a consequence, they have additional welfare concerns.

Meat broilers have been artificially selected for an extremely high feeding motivation, but are not usually feed-restricted, as this would delay the time taken for them to reach slaughter-weight. Broiler-breeders have the same highly increased feeding motivation, but must be feed-restricted to prevent them becoming overweight with all its concomitant life-threatening problems. An experiment on broilers’ food intake found that 20% of birds allowed to eat as much as they wanted either died or had to be killed because of severe illness between 11 and 20 weeks of age – either they became so lame they could not stand or they developed cardiovascular problems.[21]

Broiler breeders fed on commercial rations eat only a quarter to a half as much as they would with free access to food. They are highly motivated to eat at all times, presumably leading to chronic frustration of feeding.[40]

Because broiler breeders live to adulthood, they might show feather pecking or other injurious pecking behaviour. To avoid this, they might be beak trimmed which can lead to acute or chronic pain.

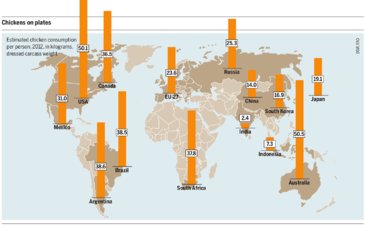

World production and consumption

A report in 2005 stated that around 5.9 billion broiler chickens for eating were produced yearly in the European Union. Mass production of chicken meat is a global industry and at that time, only two or three breeding companies supplied around 90% of the world’s breeder-broilers. The total number of meat chickens produced in the world was nearly 47 billion in 2004; of these, approximately 19% were produced in the US, 15% in China, 13% in the EU25 and 11% in Brazil.[21]

Worldwide, 86.6 million tonnes of broiler meat will be produced in 2014.[42]

Broiler industry

The commercial production of broiler chickens for meat consumption is a highly industrialized process. There are two major sectors: (1) rearing birds intended for consumption and (2) rearing parent stock for breeding the meat birds.

See also

- Animal cruelty

- Animal welfare science

- Chicken

- Chickens as pets

- Chicken tax

- Concentrated animal feeding operation

- Early feeding

- Intensive animal farming

- Poultry farming

- The Chicken of Tomorrow

References

- ↑ Kruchten, Tom (November 27, 2002). "U.S Broiler Industry Structure" (PDF). National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), Agricultural Statistics Board, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 29, 2013. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- ↑ "The Economist, July 27, 2011". July 27, 2011. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ↑ Wong, GK; et al. (2004). "A genetic variation map for chicken with 2.8 million single-nucleotide polymorphisms". Nature. 432: 717–722. PMC 2263125

. PMID 15592405. doi:10.1038/nature03156.

. PMID 15592405. doi:10.1038/nature03156. - ↑ Garrigus, W.P. (2007). "Poultry Farming". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- ↑ Liu, Yi-Ping; Wu, Gui-Sheng; Yao, Yong-Gang; Miao, Yong-Wang; Luikart, Gordon; Baig, Mumtaz; Beja-Pereira, Albano; Ding, Zhao-Li; Palanichamy, Malliya Gounder; Zhang, Ya-Ping (2006), "Multiple maternal origins of chickens: Out of the Asian jungles", Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 38 (1): 12–19, PMID 16275023, doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.09.014

- ↑ Zeder; et al. (2006). "Documenting domestication: the intersection of genetics and archaeology". Trends in Genetics. 22 (3): 139–155. PMID 16458995. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2006.01.007.

- ↑ King, Rick (February 24, 2009), "Rat Attack", NOVA and National Geographic Television

- ↑ King, R. (February 1, 2009). "Plant vs. Predator". NOVA.

- 1 2 Smith, Carolynn L.; Zielinski, Sarah L. (February 2014). "Brainy Bird". Scientific American. 310 (2): 60–65. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0214-60.

- ↑ Eriksson J, Larson G, Gunnarsson U, Bed'hom B, Tixier-Boichard M, et al. (2008) Identification of the Yellow Skin Gene Reveals a Hybrid Origin of the Domestic Chicken. PLoS Genet January 23, 2008 Genetics.plosjournals.org

- 1 2 Hardiman, J. (May 2007). "How 90 years of poultry breeding has shaped today’s industry" (PDF). Poultry International. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 25, 2012. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- ↑ "Watt Publishing History". Watt. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- 1 2 Damerow, G. 1995. A Guide to Raising Chickens. Storey Books. ISBN 0-88266-897-8

- 1 2 Smith, Kingsley (2010). "The History of Shaver Breeding Farms". Hendrix Genetics. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ↑ Senger, Phillip (2012). Pathways to Pregnancy and Parturition. Redmond: Current Conceptions Inc.

- 1 2 3 Donoghue, A; Wishart, G (2000). "Storage of Poultry Semen". Animal Reproduction Science. 62: 213–232. doi:10.1016/s0378-4320(00)00160-3.

- ↑ Robinson, F. E.; Wilson, J. L.; Yu, M. W.; Fasenko, G. M.; Hardin, R. T. (1993-05-01). "The Relationship Between Body Weight and Reproductive Efficiency in Meat-Type Chickens". Poultry Science. 72 (5): 912–922. ISSN 0032-5791. doi:10.3382/ps.0720912.

- ↑ "Artificial insemination: the state of the art". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- 1 2 Blanco, J; Wildt, D; Höfle, U; Voelker, W; Donoghue, A (2009). "Implementing artificial insemination as an effective tool for ex situ conservation of endangered avian species". Theriogenology. 71: 200–213. doi:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2008.09.019 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ↑ "Poultry Industry Frequently Asked Questions Provided by the U.S. Poultry & Egg Association" (PDF). U.S. Poultry & Egg Association. Retrieved June 21, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Turner, J.; Garcés L. and Smith, W. (2005). "The Welfare of Broiler Chickens in the European Union" (PDF). Compassion in World Farming Trust. Retrieved November 16, 2014.

- ↑ Eriksson, J., Larson G., Gunnarsson, U., Bed'hom, B., Tixier-Boichard, M., et al. (2008) Identification of the Yellow Skin Gene Reveals a Hybrid Origin of the Domestic Chicken. PLoS Genet January 23, 2008 Genetics.plosjournals.org

- ↑ Weeks, C.A.; Nicol, C.J.; Sherwin, C.M.; Kestin, S.C. (1994). "Comparison of the behaviour of broiler chickens in indoor and free-range environments". Animal Welfare. 3: 179–192.

- ↑ Moyle, J.R.; Yoho, D.E.; Harper, R.S.; Bramwell, R.K. (2010). "Mating behavior in commercial broiler breeders: Female effects". Journal of Applied Poultry Research. 19: 24–29. doi:10.3382/japr.2009-00061.

- ↑ Duncan, I.J.H.; Hocking, P.M.; Seawright, E. (1990). "Sexual behaviour and fertility in broiler breeder domestic fowl". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 26: 201–213. doi:10.1016/0168-1591(90)90137-3.

- ↑ Gentle, M.J. (2011). "Pain issues in poultry". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 135: 252–258. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2011.10.023.

- 1 2 "U.S. Broiler Performance". National Chicken Council. Retrieved June 21, 2012.

- ↑ "Ontario Canada FCR". Small Flock Poultry Farmers of Canada. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- ↑ "NZ FCR Broiler Performance". Watt AgGate. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bessei, W. (2006). "Welfare of broilers: A review". World's Poultry Science Journal. 62: 455–466. doi:10.1079/WPS2005108.

- ↑ "Broiler chicken key facts". National Chicken Council. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Compassion in World Farming – Meat chickens – Welfare issues". CIWF.org.uk. Retrieved 2011-08-26.

- ↑ Vestergaard, K.S. & Sonatra, G.S. (1999). "Relationships between leg disorders and changes in behaviour of broiler chickens". Veterinary Record. 144: 205–209. doi:10.1136/vr.144.8.205.

- ↑ Reiter, K. & Bessei, W. (1995). "Influence of running on leg weakness of slow and fast growing broilers". Proceedings 29th International Congress ISAE, Exeter, U.K., 3–5 August: 211–213.

- ↑ Mc Geown, D., Danbury, T.C., Waterman-Pearson, A.E. and Kestin, S.C. (1999). "Effect of carprofen on lameness in broiler chickens". Veterinary Record. 144: 668–671. doi:10.1136/vr.144.24.668.

- ↑ Danbury, T.C., Weeks, C.A., Chambers, J.P., Waterman-Pearson, A.E. and Kestin, S.C. (2000). "Self-selection of the analgesic drug carprofen by lame broiler chickens". Veterinary Record. 146: 307–311. doi:10.1136/vr.146.11.307.

- ↑ Dawkins, M.S, Donelly, S. and Jones, T.A. (2004). "Chicken welfare is influenced more by housing conditions than by stocking density". Nature. 427: 342–344. doi:10.1038/nature02226.

- ↑ Lauber, J.K. & Kinnear, A. (1979). "Eye enlargement in birds induced by dim light". Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology. 14: 265–269.

- 1 2 Olanrewaju, H.A.; Miller, W.W.; Maslin, W.R.; Thaxton, J.P.; Dozier, III; W.A., Purswell; J. and Branton, S.L. (2007). "Interactive effects of ammonia and light intensity on ocular, fear and leg health in broiler chickens". International Journal of Poultry Science. 6 (10): 762–769. doi:10.3923/ijps.2007.762.769.

- ↑ Savory, C.J., Maros, K. and Rutter, S.M. (1993). "Assessment of hunger in growing broiler breeders in relation to a commercial restricted feeding programme". Animal Welfare. 2 (2): 131–152.

- ↑ Meat Atlas 2014 – Facts and figures about the animals we eat, p. 41, pdf

- ↑

External links

| Look up broiler in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Broilers (poultry). |